Trypanosome Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Biosynthesis

Article information

Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei, a protozoan parasite, causes sleeping sickness in humans and Nagana disease in domestic animals in central Africa. The trypanosome surface is extensively covered by glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins known as variant surface glycoproteins and procyclins. GPI anchoring is suggested to be important for trypanosome survival and establishment of infection. Trypanosomes are not only pathogenically important, but also constitute a useful model for elucidating the GPI biosynthesis pathway. This review focuses on the trypanosome GPI biosynthesis pathway. Studies on GPI that will be described indicate the potential for the design of drugs that specifically inhibit trypanosome GPI biosynthesis.

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma brucei is a protozoan parasite whose life cycle includes residence in the tsetse fly, and which invades mammals when the fly obtains a blood meal. This protozoan causes sleeping sickness in humans and Nagana disease in domestic animals in central Africa. According to the World Health Organization, about 55 million people in 36 countries of sub-Saharan Africa live in regions that are endemic for sleeping sickness, and about 500,000 people become infected every year. If untreated or not treated properly, the disease is fatal. Treatment of African trypanosomiasis is hindered by the potent toxicity of the drugs being used, and the difficulty in their administration. No effective vaccine or orally-administered drugs have yet been developed [1].

T. brucei has 2 distinct proliferative stages; the bloodstream form, which causes sleeping sickness in humans, and the procyclic form, which resides in the tsetse fly. The surface of both forms is covered by a large amount of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins known as variant surface glycoproteins (VSG) and procyclins. In the host bloodstream, the trypanosome cell surface is densely coated with approximately 10 million VSG molecules. T. brucei escapes the host's humoral immune response by sequentially expressing structurally different forms of VSG; the parasites' genome harbors approximately 1,000 VSG genes. When a tsetse fly takes blood meal from an infected patient, the ingested bloodstream form differentiates into the procyclic form; the differentiation involves the loss of the VSG surface protein and alteration of procyclin, which is composed of several million acidic glycoproteins. Proclycins are thought to function in retarding digestion of the parasite in the tsetse fly gut [2]. It is thought that the GPI anchor is important for survival of both forms of the trypanosome and for establishment of the infection.

In this review, we focus on the trypanosome GPI biosynthesis pathway. Trypanosomes are not only pathogenically important, but also constitute a useful model for elucidating the GPI biosynthesis pathway. Studies on GPI that will be described here have indicated the potential for the design of drugs to specifically inhibit trypanosome GPI biosynthesis. This approach could be useful in the treatment of trypanosomiasis.

GPI BIOSYNTHESIS BY TRYPANOSOMES

Structures of GPI

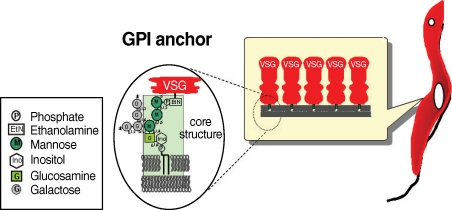

Many eukaryotic membrane proteins are covalently linked to GPI, which has unique structures containing oligosaccharides and inositol phospholipids, through post-translational modification, and are anchored to the membrane by the lipid moieties. GPI structures of some mammalian proteins, as well as protozoan parasites including T. brucei, have been investigated [3,4]. GPI anchors have a conserved core structure, which is sequentially conjugated by ethanolamine phosphate (EtNP), 3 mannoses (3Man), glucosamine (GlcN), and inositol phospholipids (EtN-PO4-6Manα1-2Manα1-6Manα1-4GlcNα1-6myo-inositol-1-PO4-lipid) (Fig. 1). There can be a wide variety of substituents in the mannoside, inositol, or lipid moieties depending on the particular protein, organism, or developmental stage of an organism. The GPI anchor of VSG contains a dimyristoylphosphatidylinositol moiety and galactose (Gal) side chain, whereas that of procyclin has predominantly 1-O-stearoyl-2-lysophosphatidylinositol and palmitoylated inositol and harbors a large and heterogeneously sialylated polylactosamine-containing side chain at the first mannose instead of at the Gal side chain [3,5-7]. Although the cell surface density of GPI-anchored proteins is generally not high in mammalian cells, such cells express a large repertoire of GPI-anchored proteins. In striking contrast, the cell surface of the protozoan parasite is densely coated predominantly by a few species of GPI-anchored proteins [8-13].

GPI biosynthesis

The GPI anchor is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by many different enzymes, which sequentially transfer sugars and EtNP to phosphatidylinositol (PI). After synthesis, the GPI anchor is attached to the protein by GPI transamidase before being transported to the cell surface [14-17].

The first step

The first step in GPI biosynthesis is initiated by the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) from uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to PI, which generates GlcNAc-PI in the cytoplasmic face of the ER. In mammalian cells, the enzyme involved in this step is GPI-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (GPI-GnT), an ER membrane-bound multiprotein complex composed of at least 7 proteins: phosphatydylinositol glycan class A; PIG-A, PIG-C, PIG-H, PIG-Q, PIG-P, dolichyl-phosphate mannosyltransferase polypeptide 2; DPM2, and PIG-Y [18-20] (Fig. 2-①, Table 1). PIG-A has been implicated in the catalytic activity of the transferase. In mammals, somatic mutation of PIG-A, which disrupts the GPI anchor biosynthesis, is involved in paroxysmal noctural hemoglobinuria (PNH) [21].

The GPI biosynthesis pathways of T. brucei and mammalian cells. The uppermost row indicates the pathway of the procyclic form of T. brucei. The middle row represents the pathway of the bloodstream form and the lowermost row depicts the pathway of mammalian cells. The reactions indicated by the circled numbers (①-⑧) correspond to those described in the text. The involved protein(s) of each step are summarized in Table 1.

The second step

The resulting GlcNAc-PI is deacetylated to yield glucosaminyl-PI (GlcN-PI) (Fig. 2-②) in a reaction catalyzed by a specific zinc metalloenzyme called N-deacetylase (deNAc, also designated PIG-L in mammals and TbGPI12 in trypanosomes), which is localized on the cytoplasmic side of the ER [22-24]. A study using trypanosomes and a HeLa cell-free system demonstrated that the trypanosome enzyme does not recognize GlcNAc-PI analogues containing 2-O-octyl-D-myo-inositol or L-myo-inositol, in contrast to the HeLa enzyme [25]. Moreover, the IC50 of potent inhibitors against trypanosome deNAc was significantly lower (approximately 8 nM) compared with human deNAc (100 µM), suggesting that the trypanosome enzyme has different substrate specificity than catalytically similar mammalian enzymes, which may be exploited as a chemotherapeutic target against trypanosomiasis [26].

The third step

GlcN-PI is likely flipped to the luminal side of the ER membrane before acylation. After this, T. brucei and mammalian GPI biosynthetic pathways diverge. In mammals, acylation of the inositol moiety of GlcN-PI, which is mediated by inositol acyltransferase (PIG-W), generates GlcN-acyl-PI before the first mannosylation [27]. In contrast, inositol acylation in trypanosomes only occurs after the first mannosylation and generates Man-GlcN-acyl-PI, indicating that inositol acylation is not a prerequisite for trypanosome mannosyl transferases (Fig. 2-③) [28,29]. Inositol acyltransferase in trypanosomes requires the presence of a hydroxyl group at the 4th position on the first mannose and a free amine on the glucosamine residue and, thus, mannosylation is required prior to inositol acylation in trypanosome GPI biosynthesis [30]. Moreover, inositol acylation and deacylation occur on multiple GPI intermediates. These results suggest that trypanosome inositol acylase and deacylase have different and broader substrate specificities than those of mammals. The enzymes responsible for inositol acylation and deacylation in T. brucei are sensitive to phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [31,32], whereas enzymes with similar activity in mammalian cells are unaffected [33]. Therefore, inositol acylation in trypanosomes is a good target for chemotherapy.

In yeasts, the efficient delivery of GlcN-acyl-PI to the first GPI-mannosyltransferase (GPI-MT-I) requires Arv1, which is a transmembrane protein containing potential zinc-binding motifs and which is a novel mediator of eukaryotic sterol homeostasis [34]. The orthologue of Arv1 with significant sequence homology has been detected only in a Plasmodium genome database but not in that of Trypanosoma (GeneDB accession no. PF100110) (data not shown).

The fourth step

In the next step, mannoses are transferred from dolichol-phosphate-mannose (Dol-P-Man) to GPI intermediates through different glycosidic linkages (Fig. 2-④). The first mannose is transferred to position 4 of the GlcN constituent of GlcN-acyl-PI by GPI-MT-I (a complex of PIG-M and PIG-X in humans) [35,36]. However, in T. brucei the first mannose is instead transferred to GlcN-PI, indicative of a different substrate specificity of GPI-MT- I between trypanosome and mammals. Moreover, GlcN-(2-O-hexadecyl)-phosphatidylinositol, a synthetic analogue of the GPI intermediate at this step, selectively inhibits trypanosomal GPI-MT-I, but not human GPI-MT-I [37]. Thus, GPI-MT-I appears to be a promising target of trypanosome-specific inhibitors, even though it has not been identified yet in trypanosomes.

Following the transfer of the first mannose, the second mannose is transferred to position 6 of the first mannose in Man-GlcN-acyl-PI by GPI α1-6 mannosyltransferase (Fig. 2-④) (GPI-MT-II, PIG-V in humans) [38]. A trypanosome orthologue has not yet been identified. Subsequently, a third mannose is transferred by GPI α1-2 mannosyltransferase III (GPI-MT-III, PIG-B in humans and TbGPI10 in trypanosomes) [39,40]. The observation that the construction of a knockout mutant of TbGPI10 is possible only when episomal TbGPI10 is introduced is consistent with the suggestion that TbGPI10 is essential for the growth of the bloodstream form of T. brucei [40]. Identification of the specific inhibitor against trypanosome GPI-MT-III with an IC50 of 1.7 µM from substrate analogs containing amino group at 2'-position of second mannose in Man2-GlcN-IPC18, a phosphate-linked C18 alkyl chain instead of Man2-GlcN-PI diacylglycerol [30], implicates TbGPI10 as a valid target of trypanosome-specific inhibitors.

The fifth step

Protein is attached to the GPI through EtNP that is transferred from phosphatidylethanolamine to position 6 of the third mannose (Fig. 2-⑤). This reaction is mediated by PIG-F and PIG-O in mammalian cells [41]. PIG-O is likely to be a catalytic component of the EtNP transferase forming a complex with PIG-F, which likely assists in stabilization of the enzyme complex. However, the orthologues of PIG-F and PIG-O have not yet been identified in trypanosomes. In mammalian cells and yeasts, an additional EtNP is added to the first (mediated by PIG-N) [42] or second mannose (mediated by PIG-F and PIG-G) [43], whereas these modifications do not occur in trypanosomes.

The penultimate step

In the T. brucei GPI biosynthetic pathway, inositol acylation takes place only after the formation of Man-GlcN-PI (Fig. 2-③). Then, the inositol-linked acyl chain can be removed or added again to any of the GPI intermediates bearing 1-3 mannoses with a dynamic equilibrium between inositol acylated and nonacylated species (Fig. 2-⑥) [29,31,44]. In mammalian cells, the inositol-linked acyl-chain remains until the mature GPI anchor is attached to the protein, whereupon it is removed by GPI inositol deacylase (PGAP1; post-GPI attachment to protein I) [45], indicating that inositol acylation and deacylation are distinctively separate events in mammalian GPI biosynthesis. In contrast, inositol is deacylated prior to attachment to VSG in bloodstream form, whereas it remains acylated in procyclins in the procyclic form. Thus, inositol deacylation likely occurs more efficiently in the bloodstream form compared with the procyclic form. Previously, a GPI inositol deacylase (GPIdeAc) gene was cloned in trypanosome and its activity demonstrated using an affinity-purified recombinant protein [46]. Inositol-acylated GPI biosynthetic intermediates accumulated in a knock-out mutant although some activity remained, suggesting that another inositol deacylase may be present [46,47]. Recently, another T. brucei GPI inositol deacylase 2 (GPIdeAc2) was cloned and was demonstrated to be essential in the bloodstream form, with its activity likely being tightly regulated in the trypanosome life cycle [48]. GPIdeAc2 is homologous to mammalian PGAP1, sharing the same lipase motif with catalytic serine [45]. However, these 2 enzymes act at different times. As mentioned above, inositol-deacylation occurs before attachment to proteins in trypanosomes, whereas the acyl chain is removed from inositol after attachment to proteins in mammalian cells [13,29,49]. Moreover, diisopropylfluorophosphate selectively inhibits inositol deacylase activity in trypanosomes, whereas mammalian inositol deacylase having a similar activity is not affected [50,51], indicating that the trypanosome inositol deacylase has a different substrate specificity and so is a good candidate drug target.

The final step (lipid remodeling of the GPI anchor)

In the last step of trypanosome GPI biosynthesis, the lipid moiety of the GPI anchor, sn-1 (C18:0) and sn-2 fatty acids (a mixture of C18-C22), is replaced with myristate (a saturated fatty acid containing 14 carbon atoms) in a lipid remodeling reaction (Fig. 2-⑦). This reaction occurs in the ER before transfer to the VSG protein. The lipid remodeling is initiated by removal of a longer fatty acid attached to the sn-2 position of glycolipid A' to form glycolipid θ, prior to acylation by attachment of myristate using myristoyl-CoA as a donor. As a next step, deacylation occurs at the sn-1 position to form the lyso species glycolipid θ'. The second myristate is then incorporated into the sn-1 position, forming dimyristated GPI (glycolipid A) on which VSG is attached. Thus, lipid remodeling consists of sequential deacylation and reacylation reactions. Recently, it has been reported that myristate transfer in GPI fatty acid remodeling in trypanosomes is mediated by TbGup1 [52]. However, the complete enzyme repertoire involved in lipid remodeling in trypanosomes remains unclear. In humans, fatty acid remodeling occurs in the Golgi after attachment of protein to the GPI anchor. Removal of the sn-2 unsaturated fatty acid from the lipid moiety of human GPI anchor requires PGAP3 [53] and replacement with stearic acid (C18:0) requires PGAP2 [54], while the sn-1 saturated fatty acid is retained in both the GPI precursor and GPI anchored protein.

GPI transamidation

After synthesis, the GPI anchor is attached to the protein by GPI transamidase before being transported to the cell surface (Fig. 2-⑧) [14-17]. GPI transamidase recognizes and cleaves the signal sequence at the C-terminus of nascent proteins and replaces it with the preassembled GPI anchor. In humans, GPI transamidase comprises at least 5 polypeptides (GAA1, GPI8, PIG-S, PIG-T, and PIG-U) [55,56]. The trypanosome GPI transamidase is also multi-enzyme complex in that 3 components (TbGAA1, TbGPI8, and TbGPI16) are homologous to human components (GAA1, GPI8, and PIG-T, respectively), and 2 other components (TTA1 and TTA2) are unique to the trypanosome enzyme [57]. TbGPI8 (GPI8 in human) is suggested to be the catalytic component responsible for cleavage of GPI-attachment signal sequences, and which is stabilized by the association with TbGPI16 through disulfide bond like mammalian GPI8 [48,55,57-66]. As mentioned above, the mammalian GPI transamidase must recognize diverse and structurally different proteins [67,68], whereas that of trypanosome processes limited kinds of proteins but which is highly expressed. Moreover, human GPI anchored protein that replaces its GPI attachment signal sequences with those of VSG does not readily become GPI-linked [69], indicating that trypanosome and mammalian GPI transamidases have different specificities against GPI anchored proteins. In addition to these protein differences, the GPI precursors themselves, which are recognized by the GPI transamidase, are structurally different. In mammalian GPIs, mannose residues are modified by extra EtNPs, whereas this modification does not occur in trypanosome, indicating that humans and trypanosomes have also different specificities against GPI anchor. Therefore, GPI transamidase in trypanosomes may be a good target for the development of anti-trypanosomal drugs.

CONCLUSION

Intensive studies of GPI for decades have revealed significant differences between mammalian and trypanosome GPI biosynthesis (Table 1). Compared with mammalian cells, trypanosomes utilize GPI for membrane anchoring of the major surface coat protein essential for its growth and survival. The specific steps in GPI biosynthesis may be potential targets for anti-trypanosomal agents. Identification of the enzymes that catalyze the specific biosynthetic steps and determination of their biochemical properties will provide the clues for revealing the specificity of the enzymes in trypanosomal and mammalian cells. Inhibitors that specifically inhibit trypanosome GPI biosynthesis without affecting the host will be a good chemotherapeutic treatment to combat trypanosomiasis. Further studies concerning inhibitor screening for inhibitory activity against trypanosome GPI biosynthesis are necessary to realize the anti-trypanosomal chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Kyungpook National University Research Fund, 2007.