Abstract

The life-span of the sparganum in humans is not exactly known, but it may survive longer than 5 years in some patients. We experienced a case infected with a sparganum that is presumed to have lived for 20 years in a patient's leg. The patient was a 60-year-old woman, and she was admitted to a hospital due to ankle pain that was aggravated on dorsiflexion. She had noticed a mass on her knee some 20 years ago, but she received no medical management for it. The mass moved into the ankle joint 3 months before the current admission, and then the aforementioned symptoms appeared. A living sparganum was recovered by surgery, and the calcified tract near the knee was proved to be the pathway along which the larva had passed.

-

Key words: sparganum, sparganosis, leg

INTRODUCTION

Sparganosis is caused by a larval tapeworm of

Spirometra sp. Human cases have been reported worldwide, but particularly in Asia. Humans can be exposed to sparganosis by consuming undercooked snakes harboring plerocercoids (= spargana), but ingesting infected copepods with procercoids through drinking water is also possible [

1]. Although sparganosis may involve internal organs, such as the eye, brain, and spinal cord [

2-

4], the disease usually manifests with a migrating subcutaneous mass. Since the mass may be non-tender, the larval tapeworm can go unnoticed until it is incidentally discovered during unrelated surgical intervention [

5]. In some cases, the precise diagnosis can be missed due to a lack of suspicion by the primary physician. We report here an interesting case of a sparganum infection that is presumed to have lived for 20 years in the leg of a Korean female patient.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old woman living in Cheonan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea, was admitted to Dankook University Hospital due to pain of the right ankle, aggravated on dorsiflexion. She had noticed a nodular mass at the medial side of the right knee 20 years ago, moving up and down very slowly. She went without any medical care for the lesion, and the mass was not notified for a long time. Three months ago, the mass was found again at the ankle of the patient, developing her ankle pain. On physical examination, an oval, rubber-like mass was found at just proximal to the lateral malleolus of the right foot. The mass was soft, non-tender, and 3 cm in diameter. In addition, another mass was found at the anterior part of the right ankle, and this produced discomfort on dorsiflexion. Routine laboratory tests were unremarkable and no eosinophilia was noted. The plain radiograph of the right leg revealed multiple calcifications extending from the medial part of the knee to the calf (

Fig. 1), but nothing was found around the ankle joint. On the MR imaging, heterogeneous signals were observed in the mass, especially near the lateral malleolus (

Fig. 2). Epidermoid cyst or dermatomyositis was suspected, and an operation was done on the mass.

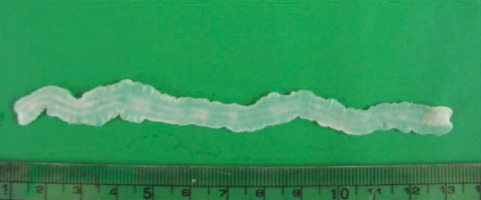

During the surgery, a small longitudinal incision was made on the upper portion of the elongated mass. A white-shiny, synovium-like piece of tissue popped out through the incision, and this was determined to be a sparganum that measured 18 cm in length and 0.5 cm in width, wriggling after removal from the patient. It was diminished to 13 cm in length and 12 mm in width after fixation in 10% formalin (

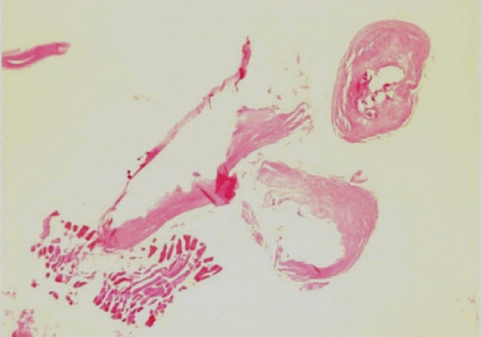

Fig. 3). The calcified foci near the calf were also removed, and the pathologic examination revealed tubular tracts in the subcutaneous tissue (

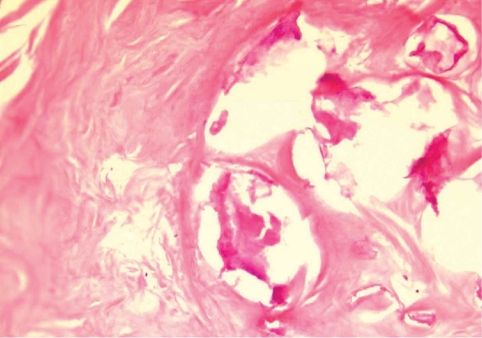

Fig. 4). These tracts possibly represented the pathway along which the larvae had passed. The tracks showed multiple, benign fibrocalcific nodular lesions with a few skeletal muscle fascicles, and the lesions were markedly degenerated (

Fig. 5). The patient was a farmer, and she denied ingesting snake or frog meat, but she admitted drinking untreated mineral water from a local mountain. On the third postoperative day, the patient was discharged and followed up uneventfully.

DISCUSSION

Sparganosis has shown a gender preference in Korea, i.e., 94 men and 25 women out of 119 cases [

6]. While the men are likely to be infected by eating raw snakes, the source of sparganosis in women may be untreated water containing parasitized copepods, including cyclops. In our case, her habit of drinking water from a local mountain could have led to the sparganum infection. Considering that many people enjoy drinking water in a mineral spring resort, surveys on the mineral water for sparganum infection are needed. Since the route of infection in a Japanese woman was proved to be eating raw carp [

7], investigations on fish should also be done.

The longevity of spargana has usually been less than a year based on the characteristics of sparganum causing evident symptoms. However, according to our patient's statement, the present sparganum is presumed to have lived for 20 years in her leg. In our case, the stakeout of the worm during its migration might be responsible for the long-term survival. There have been a few case reports of finding a live worm more than 5 years after the development of a subcutaneous mass. For example, a living worm was recovered from a Japanese woman suffering from a painful nodule for 10 years [

7], and 5-year old worm was discovered from a man in the United States [

8]. In Korea, a 10-year-survived sparganum was recovered from the patient's thigh [

9]. Although the exact time length was not estimated due to the patient's indistinct memory, the sparganum in a Filipino American woman was suspected to have been viable for 19 years [

10].

The long-term survival of parasites might be possible due to the ability to modify immune reactions of the host [

11]. In sparganosis, it was observed that IgG was cleaved into Fab and Fc fragments by an excreted-secreted (ES) cathepsin-S like protease of

Spirometra mansoni plerocercoid [

12]. It was also known that the ES products suppress the transcription of inducible nitric oxide synthase, chemokines of KC and JE, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-1β [

13,

14]. In addition, a glycoprotein separated from crude ES products of spargana was proved to suppress osteoclastogenesis and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression [

15]. Hence, the sparganum might be a valuable model for research alleviating the symptoms of immune-mediated diseases.

In a patient with sparganosis, the characteristic host tissue reaction is an elongated tract-like cavity through which a larva has passed [

16]. The sequential pathologic changes of sparganosis were reported as the followings; an inflammatory cell infiltration develops in the first week after the inoculation of the larvae into the soft tissue, tunnel-like structures appeared 2 weeks later, and a fibroblast proliferation appears about 4 weeks after that and this lasts as long as 6 months. If the larva migrates and then dies, the tunnels with inflammatory foci are replaced by granulation tissue [

17]. In the present case, the tract was replaced by granulation tissue and calcium nodules were deposited on it. Hence, the tract of this case seems to have been formed at least years ago, supporting an old age of the present worm. However, the comparison of pathologic findings between the present case and other old sparganosis was not possible since the histological examinations of sparganosis were mostly done only on the nodule containing the larva, not the migration tract. For example, histological examination of a 19-year old sparganosis revealed suppurative, granulomatous dermatitis and panniculitis with spaces containing cross-sections of a cestode larval worm [

10].

As seen in the Filipino American woman, [

10], no peripheral eosinophilia was detected in present case. Hence, if a serpiginous tubular tract is observed during imaging studies, sparganosis should be included in the differential diagnosis despite an absence of peripheral eosinophilia. From the present case, it is speculated that the longevity of spargana could be up to 20 years in man.

References

- 1. Norman SH, Kreutner AJ. Sparganosis: clinical and pathologic observations in ten cases. South Med J 1980;73:297-300.

- 2. Yoon KC, Seo MS, Park SW, Park YG. Eyelid sparganosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138:873-875.

- 3. Bharucha NE, Bhagwati SN, Kanphade MM. Epilepsy and solitary lesions. Surg Neurol 1999;52:208-209.

- 4. Kwon JH, Kim JS. Sparganosis presenting as a conus medullaris lesion; case report and literature review of the spinal sparganosis. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1126-1128.

- 5. Pampiglione S, Fioravanti ML, Rivasi F. Human sparganosis in Italy: case report and review of the European cases. APMIS 2003;111:349-354.

- 6. Min DY. Cestode infections in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1990;28(Suppl):123-144.

- 7. Kubota T, Itoh M. Sparganosis associated with orbital myositis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2007;51:311-312.

- 8. Mueller JF, Hart EP, Walsh WP. Human spargansosis in the United States. J Parasitol 1963;49:294-296.

- 9. Koo JH, Cho WH, Kim HT, Lee SM, Chung BS, Joo CY. A case of sparganosis mimicking a varicose vein. Korean J Parasitol 2006;44:91-94.

- 10. Griffin MP, Tompkins KJ, Ryan MT. Cutaneous sparganosis. Am J Dermatopathol 1996;18:70-72.

- 11. Maizels RM, Balic A, Gomez-Escobar N, Nari M, Talor MD, Allen JE. Helminth parasites-masters of regulation. Immunol Rev 2004;201:89-116.

- 12. Kong Y, Chung YB, Cho SY, Kang SY. Cleavage of immunoglobulin G by excretory-secretory cathepsin S-like protease of Spirometra mansoni plerocercoid. Parasitology 1994;109:611-621.

- 13. Fukumoto S, Hirai K, Tanihata T, Ohmori Y, Stuehr DJ, Hamilton TA. Excretory/secretory products from plerocercoids of Spirometra erinacei reduce iNOS and chemokine mRNA levels in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with cytokines and/or LPS. Parasite Immunol 1997;19:325-332.

- 14. Dirgahayu P, Fukumoto S, Tademoto S, Kina Y, Hirai K. Excretory/secretory products from plerocercoids of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei suppress interleukin-1β gene expression in murine macrophages. Int J Parasitol 2004;34:577-584.

- 15. Kina Y, Fukumoto S, Miura K, Tademoto S, Nunomura K, Dirgahayu P, Hirai K. A glycoprotein from Spirometra erinaceieuropaei plerocercoids suppresses osteoclastogenesis and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. Int J Parasitol 2005;35:1399-1406.

- 16. Cho JH, Lee KB, Yong TS, Kim BS, Park HB, Ryu KN, Park JM, Lee SY, Suh JS. Subcutaneous and musculoskeletal sparganosis: imaging characteristics and pathologic correlation. Skeletal Radiol 2000;29:402-408.

- 17. Hong ST, Kim KJ, Huh S, Lee YS, Chai JY, Lee SH, Lee YS. The changes of histopathology and serum anti-sparganum IgG in experimental sparganosis of mice. Korean J Parasitol 1989;27:261-269.

Fig. 1The plain X-ray of the patient's right leg. Note that multiple calcifications were extending from the medial part of the knee to the calf.

Fig. 2Low signal intensities (arrow) are observed around the mass lesion with mild enhancement in anterolateral aspect of the right lower leg. T1 weighted image.

Fig. 3A sparganum recovered from the patient's ankle, followed by fixation in 10% formalin under a pressure of a glass pane. The length of the worm was diminished from 18 cm to 13 cm during the fixation process.

Fig. 4A tangential cut of a serpiginous tract-like tissue recovered from the calf. It shows several discontinuous fibrocalcific nodules of variable shapes in the musculoadipose tissue. H-E stain. × 12.

Fig. 5A high-power view of the fibrocalcific nodule reveals multiple calcium soap-like deposits mainly at the central portion. H-E stain. × 200.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A case of cerebral sparganosis diagnosed by surgical resection and molecular analysis

Ryo Miyahara, Osamu Akiyama, Naoko Yoshida, Mai Suzuki, Karin Ashizawa, Takuma Kodama, Yuzaburo Shimizu, Akihide Kondo

Surgical Neurology International.2025; 16: 512. CrossRef - Cerebral sparganosis masquerading brain neoplasm: A rare incidental case

Sukhpreet Kaur, Prakriti Shukla

Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology.2023; 41: 101. CrossRef - Spirometra species from Asia: Genetic diversity and taxonomic challenges

Hiroshi Yamasaki, Oranuch Sanpool, Rutchanee Rodpai, Lakkhana Sadaow, Porntip Laummaunwai, Mesa Un, Tongjit Thanchomnang, Sakhone Laymanivong, Win Pa Pa Aung, Pewpan M. Intapan, Wanchai Maleewong

Parasitology International.2021; 80: 102181. CrossRef - A case of human breast sparganosis diagnosed as Spirometra Type I by molecular analysis in Japan

Tetsuya Okino, Hiroshi Yamasaki, Yutaka Yamamoto, Yuna Fukuma, Junichi Kurebayashi, Fumiaki Sanuki, Takuya Moriya, Hiroshi Ushirogawa, Mineki Saito

Parasitology International.2021; 84: 102383. CrossRef - Apparent Sparganosis Presenting as a Palpable Neck Mass: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Minhee Hwang, Hye Jin Baek, Sang Min Lee

Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology.2020; 81(5): 1210. CrossRef - Follow-up study of high-dose praziquantel therapy for cerebral sparganosis

Peng Zhang, Yang Zou, Feng-Xia Yu, Zheng Wang, Han Lv, Xue-Huan Liu, He-Yu Ding, Ting-Ting Zhang, Peng-Fei Zhao, Hong-Xia Yin, Zheng-Han Yang, Zhen-Chang Wang, Siddhartha Mahanty

PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.2019; 13(1): e0007018. CrossRef - Clinical Manifestation of a Patient With Forehead Sparganosis

Soung Min Kim, Emmanuel Kofi Amponsah, Mi Young Eo, Yun Ju Cho, Suk Keun Lee

Journal of Craniofacial Surgery.2017; 28(4): 1081. CrossRef - Parasitism by larval tapeworms genus Spirometra in South American amphibians and reptiles: new records from Brazil and Uruguay, and a review of current knowledge in the region

Fabrício H. Oda, Claudio Borteiro, Rodrigo J. da Graça, Luiz Eduardo R. Tavares, Alejandro Crampet, Vinicius Guerra, Flávia S. Lima, Sybelle Bellay, Letícia C. Karling, Oscar Castro, Ricardo M. Takemoto, Gilberto C. Pavanelli

Acta Tropica.2016; 164: 150. CrossRef - Human sparganosis, a neglected food borne zoonosis

Quan Liu, Ming-Wei Li, Ze-Dong Wang, Guang-Hui Zhao, Xing-Quan Zhu

The Lancet Infectious Diseases.2015; 15(10): 1226. CrossRef - Recurred Sparganosis 1 Year after Surgical Removal of a Sparganum in a Korean Woman

Young-Il Lee, Min Seo, Hyun-Woo Park

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(1): 75. CrossRef - Intramuscular Sparganosis in the Gastrocnemius Muscle: A Case Report

Jeung Il Kim, Tae Wan Kim, Sung Min Hong, Tae Yong Moon, In Sook Lee, Kyung Un Choi, Hak Sun Yu

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(1): 69. CrossRef - The genome of the sparganosis tapeworm Spirometra erinaceieuropaeiisolated from the biopsy of a migrating brain lesion

Hayley M Bennett, Hoi Ping Mok, Effrossyni Gkrania-Klotsas, Isheng J Tsai, Eleanor J Stanley, Nagui M Antoun, Avril Coghlan, Bhavana Harsha, Alessandra Traini, Diogo M Ribeiro, Sascha Steinbiss, Sebastian B Lucas, Kieren SJ Allinson, Stephen J Price, Thom

Genome Biology.2014;[Epub] CrossRef - Multiple Sparganosis

Viroj Wiwanitkit

Archives of Plastic Surgery.2014; 41(02): 181. CrossRef - Migration: A Notable Feature of Cerebral Sparganosis on Follow-Up MR Imaging

Y.-X. Li, H. Ramsahye, B. Yin, J. Zhang, D.-Y. Geng, C.-S. Zee

American Journal of Neuroradiology.2013; 34(2): 327. CrossRef - Clinical Update on Parasitic Diseases

Min Seo

Korean Journal of Medicine.2013; 85(5): 469. CrossRef - Molecular Diagnosis of Subcutaneous Spirometra erinaceieuropaei Sparganosis in a Japanese Immigrant

Yves Harder, Clarissa Prazeres da Costa, Dennis Tappe, Sven Poppert, Alexandra Haeupler, Luise Berger, Birgit Muntau, Paul Racz, Katja Specht

The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.2013; 88(1): 198. CrossRef