Non-specific Defensive Factors of the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas against Infection with Marteilioides chungmuensis: A Flow-Cytometric Study

Article information

Abstract

In order to assess changes in the activity of immunecompetency present in Crassostrea gigas infected with Marteilioides chungmuensis (Protozoa), the total hemocyte counts (THC), hemocyte populations, hemocyte viability, and phagocytosis rate were measured in oysters using flow cytometry. THC were increased significantly in oysters infected with M. chungmuensis relative to the healthy appearing oysters (HAO) (P<0.05). Among the total hemocyte composition, granulocyte levels were significantly increased in infected oysters as compared with HAO (P<0.05). In addition, the hyalinocyte was reduced significantly (P<0.05). The hemocyte viability did not differ between infected oysters and HAO. However, the phagocytosis rate was significantly higher in infected oysters relative to HAO (P<0.05). The measurement of alterations in the activity of immunecompetency in oysters, which was conducted via flow cytometry in this study, might be a useful biomarker of the defense system for evaluating the effects of ovarian parasites of C. gigas.

INTRODUCTION

The aquaculture production of Crassostrea gigas in Korea has increased markedly, from more than 40,000 tons in the 1960s to more than 960,000 tons in 1973, following the introduction of aquaculture. Since the 1990s, however, this pursuit has experienced difficulties due to poor natural seed collection [1]. The causes of this poor natural seed collection have been investigated and identified. Infections with Marteilioides chungmuensis, a paramyxean protozoa affecting the normal oviposition and development of fertilized eggs and impairing the product quality by damaging the visual attractiveness have been identified as causative factors in the reduced aquaculture production of oysters, C. gigas [2]. Studies of this ovarian parasite included the assessment of microstructures [3], process of spore formation [4], initial infection route[5], rate of infection [2,4,6,7], development of diagnostic methods [8,9], pathogenicity [2,9], biochemical examinations [6], and effects of environmental factors [10,11]. A variety of such studies have been conducted in Korea and Japan. Thus far, however, there have been no studies which characterized the mechanisms underlying host defenses against M. chungmuensis infection.

In the bivalvia, hemocytes perform activities, such as encapsulation, phagocytosis, inflammation, and wound healing for the removal of foreign bodies infiltrating the body. Thus, they perform a key role in self-defense mechanisms [12,13]. In recent years, flow cytometry has been extensively used to assess the mechanisms by which the marine bivalves exert a cellular defensive effect. This has been shown to be useful, prompt, and accurate in the quantitative analysis of the morphology and functions of each cell. Thus, this technique has been very effectively employed. To date, by employing these methods, the immune parameters of marine bivalvia, including phagocytosis, total hemocyte counts, respiratory burst, and hemocyte mortality, have been previously assessed [14,15].

Given the background outlined above, we have conducted this study to evaluate the effects of M. chungmuensis infection in C. gigas. To accomplish this, we assessed the alterations of immunecompetency factors as seen by flow cytometry in the hemocytes of oysters infected with this ovarian parasite, as well as those in healthy appearing oysters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

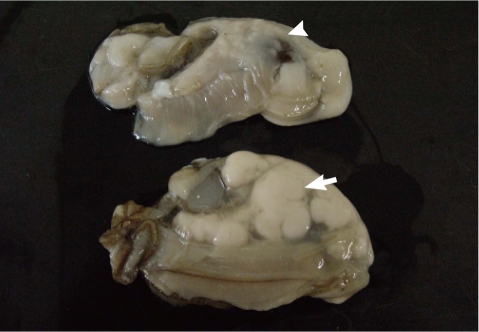

The Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, used in this study were collected 3 times from an oyster bed in Goseong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do in August 2009. The oysters were then transferred to our laboratory and used for the following experimental procedures. Oysters were divided into M. chungmuensis-infected group (Fig. 1), in which nodules were grossly formed on the mantle after removal of the shell, and healthy appearing oysters (HAO) group, where healthy findings were grossly present. After removing the shell, hemolymph was extracted from the heart with a 1-ml syringe. After extraction, hemocytes were maintained on ice to inhibit hemocyte clumping until they were needed for the experiments [16]. At the first experimental session, 18 HAO were divided into 3 groups and infected oysters (n=4) were used as 1 group. At the second session, 36 HAO were divided into 6 groups and the infected oysters (n=10) were divided into 3 groups. At the third experimental session, 36 HAO were divided 6 groups and the infected oysters (n=12) were divided into 4 groups. The hemolymph was combined into pools of oysters each to reduce individual variation.

Flow cytometric analyses of oyster hemocytes

In analysis of the extracted hemolymph, a flow cytometer was initialized with an autocomp using a single laser FACScan system (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, California, USA). Then, 10,000 cells were measured using consort 30. This was followed by an analysis of the total hemocyte counts (THC), characterization of hemocyte populations, hemocyte viability, and phagocytosis rate.

Total hemocyte count and characterization of hemocyte populations

The prescribed volume (300 µl) of hemolymph was added in a tube containing 1 µl of SYBR Green I obtained by diluting the 10×commercial solution (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and 300 µl of 6% formalin with filtered seawater before flow cytometric analysis. Te total hemocyte count, hemocyte proportions, and other cytometric measurements (i.e., size and internal complexity) were determined on SYBR Green I-positive cells. Live and dead cells containing DNA were stained by SYBR Green [17].

Measurements were then conducted with a flow cytometer. The total hemocyte (Y) counts per 1 ml of hemolymph were calculated via the following formula [18]; Y=X/60×2×1,000.

Here, 'X' represents the hemocyte counts measured with a flow cytometer; '60' represents the flow rate of the flow cytometer per min; '2' represents the dilution coefficient; and '1,000' represents the constant by which µl can be converted to ml.

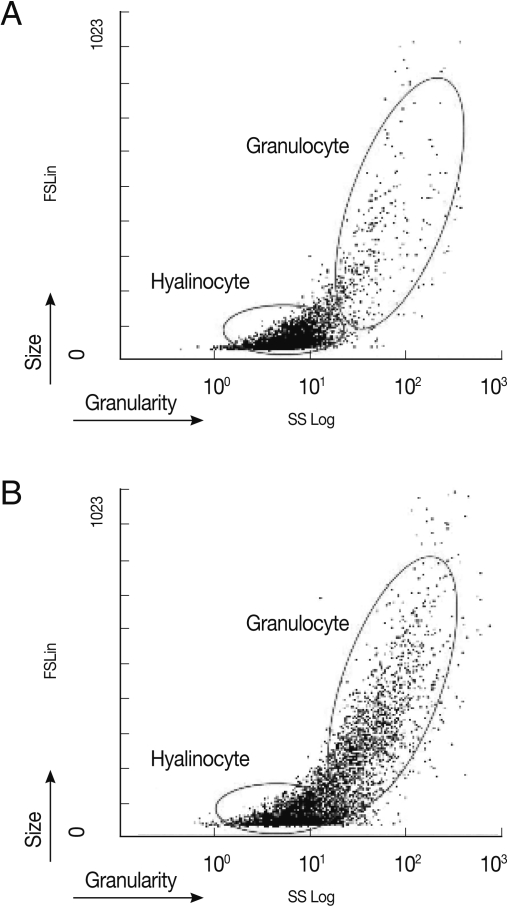

Hemocyte subtypes were discriminated based upon relative flow cytometric morphological parameters, Forward Scatter (FSC), and Side Scatter (SSC). FSC and SSC commonly measure particle size and internal complexity, respectively [16].

Hemocyte viability

Hemocyte viability was assayed with a Live/Dead® Viability/Cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) as described by Choi et al. [19]. This kit quickly discriminates live from dead cells by simultaneously staining with green fluorescent calcein-AM to indicate intracellular esterase activity and red fluorescent ethidium homodimer-1 to indicate loss of plasma membrane integrity. A 300-µl of hemolymph was added along with 1 µl of calcein-AM and 2 µl of 2 mM EthD-1 (ethidium homodimer-1), and diluted with DMSO, and the reaction was conducted in a dark room for 30 min. This was followed by measurements of hemocyte viability with a flow cytometer.

Phagocytosis rate

According to the total hemocyte count, hemolymph was added to the filtered sea water. Thus, the number of cells was set at approximately 1×106 cell/ml. A 3-µl of FITC-Zymosan (Sigma) was added at a volume of 300 µl hemolymph. The phagocytic activity was induced for 30 min in a dark room at 25℃ [20]. This was followed by addition of hemolymph fluid and an identical volume of 6% formalin. Finally, the phagocytosis rate was measured using a flow cytometer. As a negative control which is without zymosan, hemolymph was cultured for 30 min at 25℃ in a dark room. With the addition of 6% formalin, the phagocytosis rate was measured with a flow cytometer.

Statistical analyses

In order to evaluate the alterations in the activity of hosts immunecompetency depending on differences in parasitic infections in each parameter, a t-test was conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), Version 18.0. In addition, we conducted an analysis of the simple correlations between the parameters via Spearman's correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

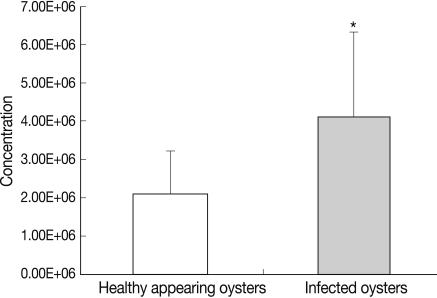

Total hemocyte count

In HAO, the hemocyte counts were 3.9×106 cell/ml at the first experimental session, 1.8×106 cell/ml at the second experimental session, and 2.7×106 cell/ml at the third experimental session. Additionally, in the oysters infected with ovarian parasites, the hemocyte counts were 7.9×106 cell/ml, 5.0×106 cell/ml and 2.0×106 cell/ml respectively (Fig. 2). Total hemocyte counts differed significantly between the oysters infected with ovarian parasites (mean value; 4.12×106±0.70×106 cell/ml, SD; 2.2×106) and the healthy appearing ones (mean value; 2.11×106±0.36×106 cell/ml, SD; 1.13×106) (P<0.05), and the degree of difference between the 2 groups was twice that value (Table 1).

Total hemocyte counts of healthy appearing oysters and M. chungmuensis-infected oysters evaluated via flow cytometry. *P<0.05.

Characterization of hemocyte populations

C. gigas hemocytes were classified on the basis of their size and granularity, and were divided into hyalinocytes (low SSC and low FSC) and granulocytes (high SSC and high FSC) (Fig. 3). In HAO, hyalinocytes were measured at 81.8±5.5%, and granulocytes were measured at 16.9±5.5%. In the M. chungmuensis-infected oysters, hyalinocytes were measured at 73.0±7.3% and granulocytes were measured at 25.2±7.2%. In the infected oysters, the granulocytes increased significantly as compared with HAO (P<0.05). In addition, hyalinocyte levels were reduced significantly (P<0.05).

Hemocyte viability

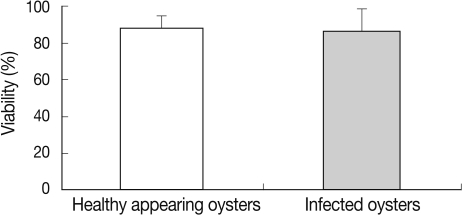

In HAO, the hemocyte viability was 78.7% in the first, 87.2% in the second, and 94.5% in the third experimental session. In M. chungmuensis-infected oysters, the hemocyte viability was 55.1% in the first experimental session, 85.0% in the second, and 93.6% in the third (Fig. 4). The hemocyte viability was 88.6±1.9% (SD; 6.0) in HAO and 86.3±4.0% (SD; 12.7) in the oysters infected with M. chungmuensis (Table 1). No significant differences in hemocyte viability were noted between the M. chungmuensis-infected and HAO (P>0.05) (Fig. 4). After an analysis of the simple correlation between the defensive factors contained in the hemocytes of both M. chungmuensis-infected and HAO (Table 2), the hemocyte viability was correlated negatively with the total hemocyte counts in the M.chungmuensis-infected oysters (P<0.05).

Viability of healthy appearing oysters and M. chungmuensis-infected oysters evaluated via flow cytometry.

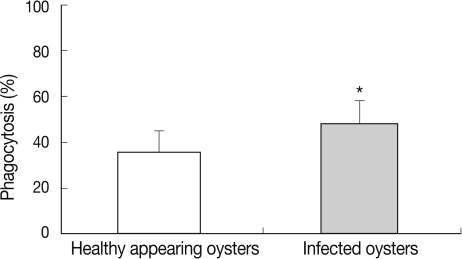

Phagocytosis rate

In HAO, the phagocytosis rate was 35.9% in the first experimental session, 39.8% in the second, and 34.5% in the third. In oysters infected with ovarian parasites, the phagocytosis rate was measured as 36.8% in the first experimental session, 41.9% in the second, and 50.5% in the third (Fig. 5). The phagocytosis rate was significantly higher in the oysters infected with M. chungmuensis relative to HAO (48.1±3.1% [SD; 8.9] vs 36.3±2.8% [SD; 9.9]) (P<0.05) (Table 1). After an analysis of the simple correlation between the defensive factors contained in the hemocytes of both M. chungmuensis-infected and HAO (Table 2), the phagocytosis rate was positively correlated with the total hemocyte counts (P<0.05). The phagocytosis rate increased at higher degrees of hemocyte viability during the control of pathogenic agents, and the hemocyte viability was reduced despite the elevation of total hemocyte counts as a defense mechanism (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, in order to measure the activity of defensive factors including the phagocytic activity of C. gigas infected with M. chungmuensis, the immunological functions of hemocytes was evaluated using a flow cytometer. According to the findings of the current study, the total hemocyte counts were significantly higher in M. chungmuensis-infected oysters relative to HAO. In Mytilus galloprovincialis infected with Marteilia refrigens, the hemocyte counts have been shown to be significantly higher [21]. In Tapes philippinarum, also as the result of infection with Perkinsus and the reciprocal actions associated with exposure to detrimental algae, the circulating hemocyte counts are significantly affected [22]. As described herein, parasite infections have been reported to affect the total hemocyte counts.

In shellfish, the hemocytes have been variously classified according to their morphology, cytochemical properties, and immunological functions. According to most investigators, however, they can be classified into 2 types, granulocytes and hyalinocytes [23]. The granulocytes had an excellent phagocytic activity profile as compared with the hyalinocytes [24,25]. According to our study, the phagocytosis rate was significantly higher in M. chungmuensis-infected oysters, in which granulocytes increased significantly relative to HAO (P<0.05) (Fig. 5).

Additionally, as shown in Table 2, in M. chungmuensis-oysters, the total hemocyte counts and hemocyte viability were negatively correlated, with a Spearman's correlation coefficient of 0.9 (P<0.05). In contrast, the hemocyte viability in bivalves infected with Perkinsus marinus [26] and Vibrio tapetis [27] was significant. Our study demonstrated that the parasite infection could stimulate phagocytosis of hemocytes. The involvement of hemocytes in mollusk cellular immune responses mainly relies on their capacity to engulf and subsequently degrade foreign material through phagocytosis [13,28], as oyster immunity is the primary defense against pathogens [29].

It was also noted, however, that the phagocytosis rate increased at higher degrees of hemocyte viability during the control of pathogenic agents, and the hemocyte viability was reduced despite the elevation of total hemocyte counts as a defense mechanism (Table 2). These findings demonstrate that the hemocyte had a very powerful endocytotic capacity based on the phagocytotic activity, although it underwent apoptosis because it could not induce intracellular degradation against protozoan species. Despite their prompt responsiveness, they have been reported to mount no effective responses to protozoan species, such as Perkinsus and Bonamia [30,31].

According to our study, on flow cytometry, the total hemocyte counts were increased in oysters as the result of infection with M. chungmuensis. In particular, it was also demonstrated that the phagocytosis rate was raised as the result of increased proportions of granulocytes. This measure may not directly reflect an immune capacity, although most studies on bivalves use it as a biomarker of the defense system [26,32]. The measurement of alterations in the activity of defense parameters in oysters might prove to be a useful method for assessing the effects of M. chungmuensis on C. gigas. This might also be proven useful in evaluating the immunological status of hosts, thereby determining their health status.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Fisheries Research and development Institute (NFRDI), Republic of Korea.