Thelazia rhodesii in the African Buffalo, Syncerus caffer, in Zambia

Article information

Abstract

We report 2 cases of Thelazia rhodesii infection in the African buffaloes, Syncerus caffer, in Zambia. African buffalo calves were captured from the livestock and wildlife interface area of the Kafue basin in the dry season of August 2005 for the purpose to translocate to game ranches. At capture, calves (n=48) were examined for the presence of eye infections by gently manipulating the orbital membranes to check for eye-worms in the conjunctival sacs and corneal surfaces. Two (4.3%) were infected and the mean infection burden per infected eye was 5.3 worms (n=3). The mean length of the worms was 16.4 mm (95% CI; 14.7-18.2 mm) and the diameter 0.41 mm (95% CI; 0.38-0.45 mm). The surface cuticle was made of transverse striations which gave the worms a characteristic serrated appearance. Although the calves showed signs of kerato-conjunctivitis, the major pathological change observed was corneal opacity. The calves were kept in quarantine and were examined thrice at 30 days interval. At each interval, they were treated with 200 µg/kg ivermectin, and then translocated to game ranches. Given that the disease has been reported in cattle and Kafue lechwe (Kobus lechwe kafuensis) in the area, there is a need for a comprehensive study which aims at determining the disease dynamics and transmission patterns of thelaziasis between wildlife and livestock in the Kafue basin.

Spirurid nematodes belonging to the genus Thelazia Bosc, 1819 are helminths that infect the conjunctival sac and lacrimal ducts of animals [1]. They are transmitted by flies of the genus Musca. They cause a variety of clinical signs that include conjunctivitis, keratitis, excessive lacrimation, corneal opacity, corneal ulceration, and photophobia [1]. In Zambia, the earliest reports of Thelazia sp. infection was in 1955 in the Kafue lechwe (Kobus leche ka uensis) found in the Kafue basin [2]. Thus far, the disease has been reported only in Kafue lechwe [2,3] and cattle [4] in the Kafue basin. In the present study, we report Thelazia rhodesii (Desmarest, 1828) infection in the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in the wildlife and livestock interface area of the Kafue basin in Zambia.

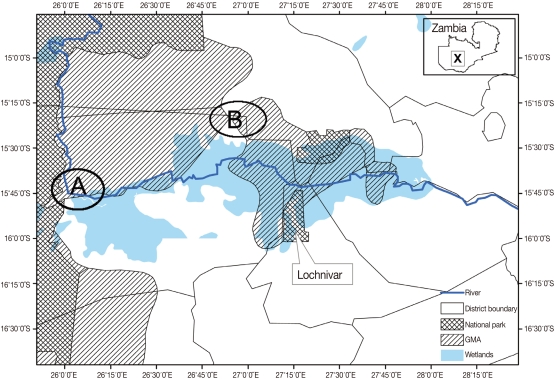

This study was carried out at Nanzhila (Fig. 1) in the Kafue flats game management area (GMA). The area is a wetland which supports a transhumance grazing system for the traditional livestock farmers by providing grazing pastures for cattle coming from the surrounding areas in the dry season. GMAs are considered to be buffer zones also referred to as 'livestock and wildlife interface areas' because they are located between National Parks (NP) and communal lands thereby allowing for the co-existence of domestic animals and wildlife [5]. In August 2005, a total of 48 buffalo calves were captured for the purpose of translocation to game ranches. The calves were immobilized using M99 (etorphine hydrochloride, Novartis, Johannesburg, South Africa) and reversed using M5050 revivon (dreprenorphine, Novartis) at capture. The calves were quarantined for 60 days prior to translocation. Their age was estimated at 4-6 months using tooth development [6].

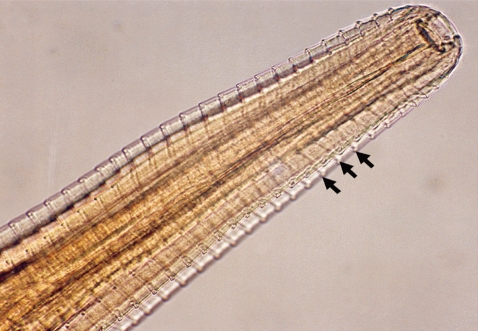

Soon after immobilization, the conjunctival sacs and corneal surfaces of the eyes were gently examined by manipulating the orbital membranes in order to check for the presence of eye-worms. Adult worms were collected using forceps and preserved in 10% formalin for identification. Swabs were also collected from the eyes of each calf and transported to the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Zambia in Lusaka. We examined the worms using a microscope (100×) and they were identified as Thelazia rhodesii as described by Soulsby [7]. Of the 48 calves examined, only 2 were infected giving a prevalence of 4.3% (n=48). The number of worms collected from the infected eyes varied between 4 and 6. One calf had only 1 infected eye while the other had both and we estimated the infection burden at 5.3 worms per infected eye (n=3). We measured the length and diameter of the worms and they were estimated at 16.4 mm (95% CI; 14.7-18.2 mm) and 0.41 mm (95% CI; 0.38-0.45 mm), respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, the surface cuticle had transverse striations cutting across the body surface in a serrated pattern. Both calves showed signs of inflammation in the conjunctiva and cornea leading to kerato-conjunctivitis, although the most prominent pathological change observed in all 3 eyes at the time of capture was corneal opacity (Fig. 3).

Anterior part of a Thelazia rhodesii worm detected from an African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) calf in the Kafue basin of Zambia. Arrows indicate areas of striations cutting across the surface cuticle of the worm.

It is likely that the infection could have started as kerato-conjunctivitis subsequently resulting in corneal opacity as the disease advanced. For the calf that had both eyes infected, it showed signs of poor visibility in the early stage after capture. However, it gained its sight as the corneal opacity resolved. There was no corneal opacity detected in the rest of the calves (46/48) which did not have T. rhodesii eye-worms. We did not carry out investigations to rule out the possibility of other organisms such as Moraxiella bovis in causing the corneal opacity observed in the affected calves. Besides, the sample size was too small to carry out statistical analysis aimed at determining the correlation between the occurrence of corneal opacity and infection with T. rhodesii. All calves were treated with ivermectin (200 µg/kg) administered subcutaneously (Norvatis). There was no topical conjunctival therapy administered to treat the corneal opacity. The calves were re-examined after 30 days and no eye-worms were detected. A second dose of ivermectin (200 µg/kg) was administered and the calves were re-examined after another 30 days. After examining the calves the third time and no eye-worms detected, the calves were translocated to game ranches after receiving a third dose of ivermectin. The objective of giving the second and third doses of ivermectin was to ensure that the calves were free from the infection given that Thelazia spp. have been reported to survive in the eyes of infected animals for several months [1].

Soll et al. [8] demonstrated that T. rhodesii is susceptible to ivermectin levels present in the lacrimal fluid and conjunctiva of cattle treated subcutaneously with ivermectin at 200 µg/kg. Ghirotti and Iliamupu [4] reported a variation between season and age on the prevalence of T. rhodesii in cattle in Zambia. They [4] noted that eye lesions in cattle have a seasonal pattern in Zambia with the peak being between November and February in the rainy season which coincides with the peak of T. rhodesii infections. They attributed these observations to the climatic conditions which are more favorable for the survival of the intermediate hosts in the rainy season than in the dry season when the lack of environmental humidity inhibits the development of the insect intermediate hosts. They reported a low prevalence (3.1%, n=223) in the dry season compared to the rainy season (26.6%, n=248) and they observed that adult cattle were more frequently affected than calves. Similarly, Kennedy et al. [9] and Van Aken et al. [10] reported high prevalences in adult animals than calves. It is likely that the prevalence in buffaloes could vary with age and season although there has been no study aiming at comparing the prevalence between adult buffaloes and the calves as well as comparing the variation between seasons.

It is interesting to note that the study area covered by Ghirotti and Iliamupu [4] who recorded a relatively high prevalence in cattle (26.6%, n=248) included the Lochinvar NP where T. rhodesii was reported in Kafue lechwe [2,3] and that the Nanzhila area covered in the present study are all parts of the Kafue flats ecosystem (Fig. 1). It is likely that eye-worms infecting cattle are also infecting wildlife in the Kafue flats ecosystem. Even though we found corneal opacity in the infected calves (Fig. 3), we did not establish the relationship between the presence of the worms and corneal opacity in the present study. Ghirotti and Iliamupu [4] did not find any correlation between the infection of T. rhodesii and the presence of corneal opacity in cattle. T. rhodesii is considered to be a predisposing factor for other secondary invading organisms through mechanical damage caused by the serrated cuticles on the edges of the parasite [11]. Hence, severe pathological changes observed in T. rhodesii infection might be caused by secondary invading organisms as a result of mechanical damage caused by serrated cuticles on the edges of T. rhodesii eye-worms which gives entry for bacterial and viral infections. Although eye-worm infections are unlikely to cause mortality, its association with conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal opacity, and blindness has a negative conservation impact because affected animals have the risk of being vulnerable to predations because of failure to effectively defend themselves from predators due to poor visibility. To fully understand the transmission patterns, prevalence, and impact of eye-worm infections in wildlife, there is need to synchronize wildlife and livestock investigations in the Kafue basin.