Abstract

We report here a case of inguinal sparganosis, initially regarded as myeloid sarcoma, diagnosed in a patient undergone allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation (HSCT). A 56-year-old male patient having myelodysplastic syndrome was treated with allogeneic HSCT after myeloablative conditioning regimen. At day 5 post-HSCT, the patient complained of a painless palpable mass on the left scrotum and inguinal area. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography revealed suspected myeloid sarcoma. Gun-biopsy was performed, and the result revealed eosinophilic infiltrations without malignancy. Subsequent serologic IgG antibody test was positive for sparganum. Excisional biopsy as a therapeutic diagnosis was done, and the diagnosis of sparganosis was confirmed eventually. This is the first report of sparganosis after allogeneic HSCT mimicking myeloid sarcoma, giving a lesson that the physicians have to consider the possibility of sparganosis in this clinical situation and perform adequate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

-

Key words: Sparganum, sparganosis, myeloid sarcoma, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, myelodysplastic syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Sparganosis is an infectious disease caused by the plerocercoid larva of

Spirometra species tapeworms. Human infection comes from eating undercooked meat, especially the snake or frog, or ingesting water contaminated with infected cyclops. Clinical manifestations are diverse, including non-specific discomfort, vague pain, palpable mass, headach, or even no symptoms [

1]. Most infection is presented with lumps in soft tissues, such as subcutaneous tissues or muscles in healthy adults [

2-

4]. In some cases, it is developed among immune-compromised patients, including AIDS patients, renal allograft recipients and patients with advanced solid tumors [

5-

8]. Herein, we report a case of human sparganosis manifested overtly and mimicking myeloid sarcoma in a patient undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

CASE DESCRIPTION

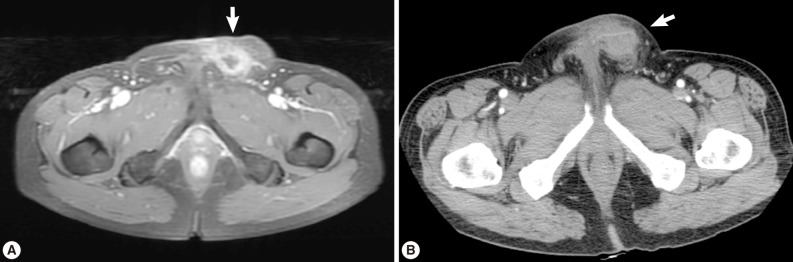

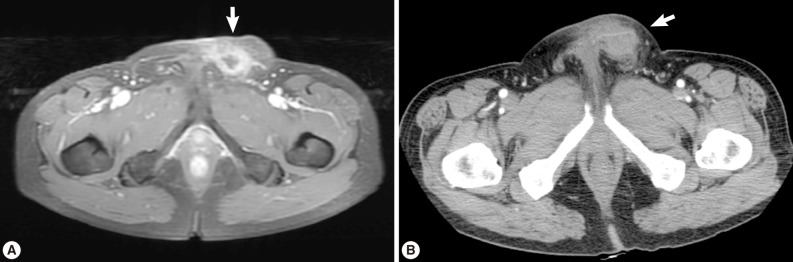

A 56-year old male visited our out-patient clinic for pancytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy and karyotype analysis showed myelodysplastic feature with 14% blast count and normal karyotype, indicating MDS, refractory anemia with excessive blast. He received 4 cycles of decitabine treatment during searching for matched unrelated donor, and partial response was shown. Allogeneic peripheral HSCT with myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of busulphan and cyclophosphamide was performed from a HLA full-matched unrelated donor. However, at day 5 post-HSCT, 5 cm-sized hard and movable mass in the left scrotum and multiple palpable lymph nodes was detected at the left inguinal area. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography were done and it was suspected initially as a myeloid sarcoma in the subcutaneous fat layer of the left scrotum and pathologic lymphadenopathy at the left inguinal area (

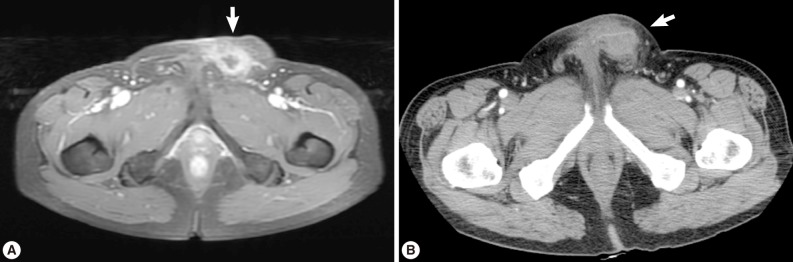

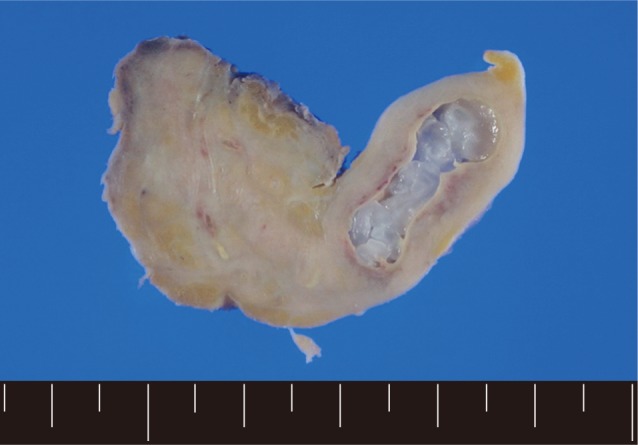

Fig. 1). In order to confirm the diagnosis, gun biopsy was done on the left scrotal mass to avoid bleeding due to thrombocytopenia after HSCT. The result of the gun biopsy was inflamation of fibrovascular soft tissues with extensive interstitial eosinophilic infiltrations without evidence of malignancy. Persistent peripheral eosinophilia was also developed after HSCT. Subsequently, IgG antibody tests for paragonimiasis, cysticercosis, sparganosis, and clonorchiasis were done, and the results were positive for sparganosis and negative for all others. We re-evaluated the patient's past history and found out that he had swam in the river and ate raw fish, cow liver, and pork meat frequently when he was young. For a next step, excision biopsy was done as an approach for therapeutic diagnosis after recovery of thrombocytopenia. The cut surface of the biopsied specimen showed a cyst filled with whitish and myxoid tissues, measuring 2.0×0.6 cm (

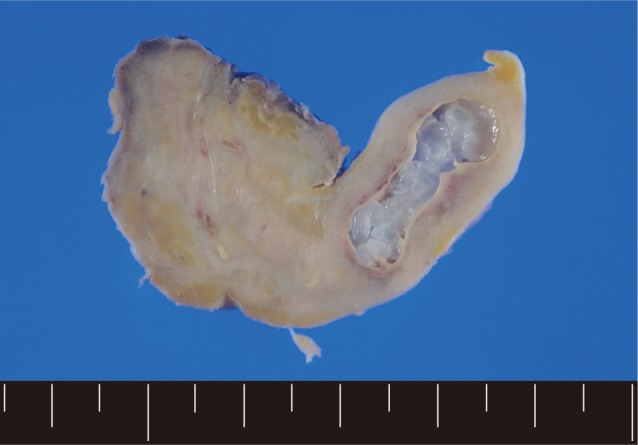

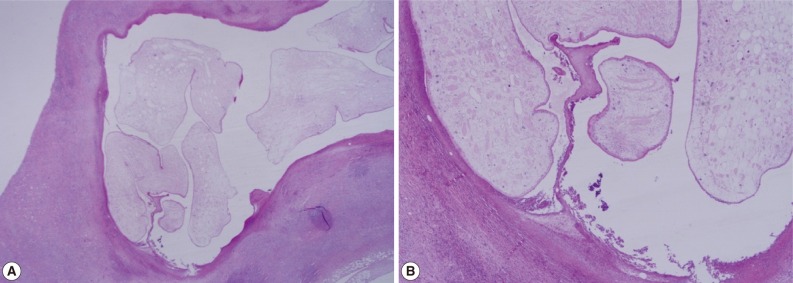

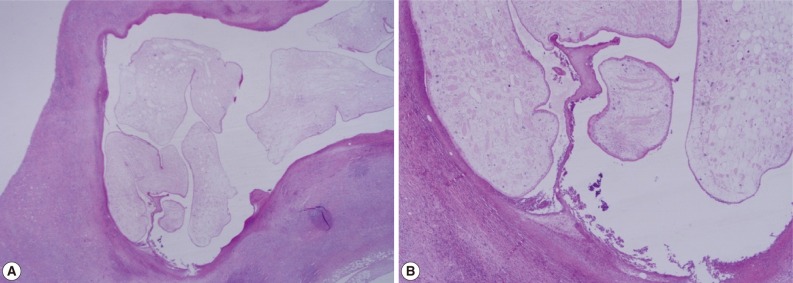

Fig. 2). The biopsy result was severe acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis with a sparganum worm (

Fig. 3). He was discharged after complete wound healing and stabilization of the post-HSCT condition.

DISCUSSION

Most sparganosis cases present as lumps in subcutaneous tissues or intermuscular fascia, which are non-tender and sometimes resolve spontaneously. Therefore, the diagnosis is often made incidentally by an imaging study or surgical biopsy in many cases. Because of late diagnosis, the sparganum worm is presumed to have lived many years, and even a 10-year survived sparganum was reported [

9]. The final diagnosis is done by the surgical biopsy proving the presence of the worm. However, immunodiagnosis is also recommended to establish a preoperative diagnosis when soft tissue tumors are detected in patients living in endemic areas [

3].

Sometimes, mass-like lesions of sparganosis are confused as solid tumors or other benign diseases, such as varicose vein, whereas there have been no reported cases mimicking myeloid sarcoma [

8-11]. In our case, the left inguinal movable mass was initially suspected as a myeloid sarcoma, which is the extramedullary manifestation of acute leukemia, by initial imaging techniques. However, the positive anti-sparganum IgG antibody test after a gun-biopsy suggested sparganosis rather than malignancy.

There were few reports of sparganosis developed in immune-compromised patients, including malignancy, AIDS, and renal allograft recipients [

5-

7]. In our case, the immunosuppressive condition of transplantation might have brought out the hidden clinical presentation of the pre-existing sparganum infection. However, the causality between this condition and the development of sparganosis is unclear because the time of mass development from transplantation was too short, and the possibility of sustained sparganosis before transplantation also existed.

This is the first case of inguinal sparganosis mimicking myeloid sarcoma. This case suggests that physicians have to give an effort to exclude sparganosis with careful diagnostic approaches, including a detailed history taking, serologic test for parasites, optimal image techniques, and tissue obtainment when they face mass-forming lesions in patients under these clinical situations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Inha University Research Grant.

References

- 1. Mueller JF. The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 1974;60:3-14.

- 2. Cho SY, Bae JH, Seo BS. Some aspects of human sparganosis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1975;13:60-77.

- 3. Kim JR, Lee JM. A case of intramuscular sparganosis in the sartorius muscle. J Korean Med Sci 2001;16:378-380.

- 4. Yun SJ, Park MS, Jeon HK, Kim YJ, Kim WJ, Lee SC. A case of vesical and scrotal sparganosis presenting as a scrotal mass. Korean J Parasitol 2010;48:57-59.

- 5. François A, Favennec L, Cambon-Michot C, Gueit I, Biga N, Tron F, Brasseur P, Hemet J. Taenia crassiceps invasive cysticercosis: A new human pathogen in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome? Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:488-492.

- 6. Meric R, Ilie MI, Hofman V, Rioux-Leclercq N, Michot L, Haffaf Y, Nelson AM, Neafie RC, Hofman P. Disseminated infection caused by Sparganum proliferum in an AIDS patient. Histopathology 2010;56:824-828.

- 7. Yoo BH, Hwang SH, Park JH, Kim BS, Song HC, Lee JM, Yang CW, Kim SY, Bang BK, Chang ED. A case of sparganosis in renal allograft recipient. J Korean Soc Transplant 2000;14:115-117.

- 8. Lee JS, Park SJ, Park MI, Kim KJ, Moon W, Shin EK, Park DY. A case of sparganosis mimicking a skin metastasis in a patient with stomach cancer. Korean J Med 2009;77:755-758.

- 9. Koo JH, Cho WH, Kim HT, Lee SM, Chung BS, Joo CY. A case of sparganosis mimicking a varicose vein. Korean J Parasitol 2006;44:91-94.

- 10. Tung CC, Lin JW, Chou FF. Sparganosis in male breast. J Formos Med Assoc 2005;104:127-128.

Fig. 1(A) Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging which shows a peripherally enhanced tubular lesion in T1-weighted image at a left subcutaneous fat layer of the left scrotum. (B) Pelvic computed tomography which shows an irregular-shaped enhanced soft tissue density lesion with peripheral infiltrations at a left subcutaneous fat layer of the left scrotum.

Fig. 2A grayish soft tissue cut surface showing a cyst filled with whitish myxoid tissues of the plerocercoid larva (sparganum).

Fig. 3(A) Chronic inflammation and fibrotic tissues with sparganosis (H&E stain, ×25). (B) Cystic structures surrounded by fibrotic tissues and containing a folded parasite (sparganum), (H&E stain, ×100).

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Human Sparganosis in Korea

Jeong-Geun Kim, Chun-Seob Ahn, Woon-Mok Sohn, Yukifumi Nawa, Yoon Kong

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2018;[Epub] CrossRef - Scrotal Sparganosis Mimicking Scrotal Teratoma in an Infant: A Case Report and Literature Review

Yi-Ming Zhao, Hao-Chuan Zhang, Zhong-Rong Li, Hai-Yan Zhang

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(5): 545. CrossRef