Ticks Collected from Wild and Domestic Animals and Natural Habitats in the Republic of Korea

Article information

Abstract

Ticks were collected from 35 animals from 5 provinces and 3 metropolitan cities during 2012. Ticks also were collected by tick drag from 4 sites in Gyeonggi-do (2) and Jeollabuk-do (2) Provinces. A total of 612 ticks belonging to 6 species and 3 genera were collected from mammals and a bird (n=573) and by tick drag (n=39). Haemaphyalis longicornis (n=434) was the most commonly collected tick, followed by H. flava (158), Ixodes nipponensis (11), Amblyomma testudinarium (7), H. japonica (1), and H. formosensis (1). H. longicornis and H. flava were collected from all animal hosts examined. For animal hosts (n>1), the highest Tick Index (TI) was observed for domestic dogs (29.6), followed by Siberian roe deer (17.4), water deer (14.4), and raccoon dogs (1.3). A total of 402 H. longicornis (adults 86, 21.4%; nymphs 160, 39.8%; larvae 156, 38.9%) were collected from wild and domestic animals. A total of 158 H. flava (n=158) were collected from wild and domestic animals and 1 ring-necked pheasant, with a higher proportion of adults (103, 65.2%), while nymphs and larvae only accounted for 12.7% (20) and 22.2% (35), respectively. Only 7 A. testudinarium were collected from the wild boar (6 adults) and Eurasian badger (1 nymph), while only 5 I. nipponensis were collected from the water deer (4 adults) and a raccoon dog (1 adult). One adult female H. formosensis was first collected from vegetation by tick drag from Mara Island, Seogwipo-si, Jeju-do Province.

INTRODUCTION

Wild and domestic mammals and birds are hosts for known and unknown zoonotic pathogens, including tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, Anaplasma, Bartonella, and Borrelia spp. [1,2]. Recently, a patient was diagnosed with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), a virus first reported in China in 2009 and Japan in 2011 and transmitted by Haemaphysalis longicornis [3,4,5,6]. In the Republic of Korea (ROK), from May to November 2013, a total of 35 patients have been confirmed with SFTS, of which there were 16 deaths (45.7%) since the first patient was confirmed in Gangwon-do on 21st May 2013.

Approximately 70% of the Korean landscape is mountainous. As a result of a national tree planting policy instituted in the 1960s, young to mature planted groves and volunteer trees now cover mountains and hillsides. These forests provide harborage for wild and feral mammals (i.e., water deer, Hydropotes inermis; Siberian roe deer, Capreolus pygargus; wild boar, Sus crofa; raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides; leopard cat, Prionalurus bengalensis; Eurasian badger, Meles leucurus; weasel, Mustela sibirica; rodent; soricomorph; feral cat, Felis catus; and feral dog, Canis lupus) and forest dwelling birds like ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) that are host to a number of ectoparasites and pathogens they harbor [2]. Agriculture, construction, military operations and training, and increased recreational activities corresponding to peak activity of ticks increase exposure to zoonotic pathogens. Therefore, comprehensive tick-borne disease surveillance programs that include host-vector-pathogen relationships provide a better understanding of the diversity of hosts and host-ectoparasite-zoonotic pathogen relationships that impact on the health of domestic animals, birds, and humans.

The purpose of this tick surveillance program was to identify hosts, associated ticks, and zoonotic pathogens (reported separately), and tick indices (TIs) for ticks collected from wild and domestic mammals, birds, and vegetation in the ROK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

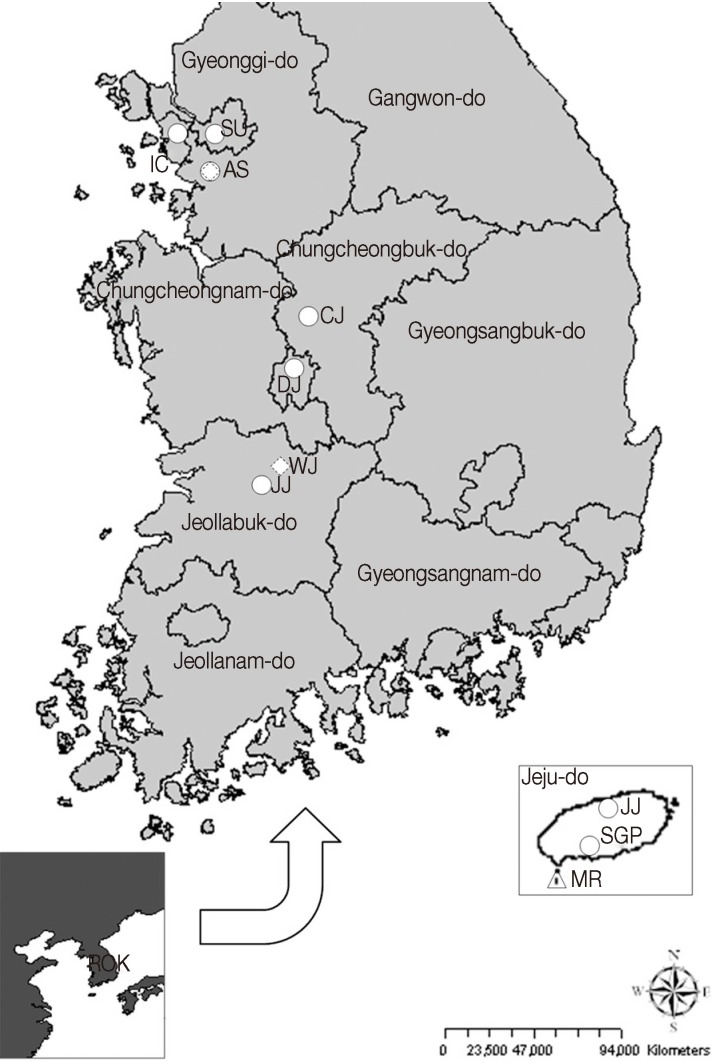

Ticks were collected from wild and domestic mammals, a ring-necked pheasant, and vegetation (tick drag) in the ROK as a part of the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR) project (Fig. 1). Mammals and a bird were examined for ectoparasites and ticks removed and provided to Seoul National University (SNU) through the SNU sampling network (e.g., wildlife rescue centers, veterinary hospitals, zoos, and legal hunters) during 2012 (Table 1). Mammals and a bird were identified to species using morphological methods and given a unique collection number. Ticks removed were placed in 15 or 50 ml conical tubes containing 100% ethyl alcohol (EtOH), and labeled with a unique collection number. Ticks also were collected and transported to SNU from vegetation (e.g., mainly grass and shrub vegetation at deer and cattle farms, province and local parks, and resident areas) by SNU researchers during 2012. Ticks collected by drag were similarly placed in conical tubes with 100% EtOH and labeled with a unique collection number. Ticks were identified to species, developmental stage, and sex (adults) under a dissecting microscope using conventional taxonomic keys [7,8,9]. Mammals and a bird that were rescued, killed on highways, or legally hunted were examined under separate institutional approved animal use protocols. TIs were calculated as: the numbers of ticks collected from hosts/total number of hosts, by species.

Map of the surveyed areas. IC, Incheon; SU, Seoul; AS, Ansan; CJ, Cheongju; DJ, Daejeon; WJ, Wanju; JJ, Jeonju (Jeollabuk-do); JJ, Jeju (Jeju-do); SGP, Seogwipo; MR, Mara-do.

RESULTS

A total of 573 ticks belonging to 3 genera (Haemaphysalis, Ixodes, and Amblyomma) and 6 species were collected from 27 wild (4 families, 5 species) and 7 domestic (1 family, 1 species) mammals and from 1 ringed-necked pheasant (Table 1). A total of 9 Siberian roe deer were examined for ticks, followed by water deer (8), raccoon dogs (8), and domestic dogs (7), wild boar (1), Eurasian badger (1), and ring-necked pheasant (1).

Among the ticks collected, H. longicornis (402) was the most frequently collected species from mammalian/avian hosts, followed by H. flava (158), A. testudinarium (7), H. nipponensis (5), and H. japonica (1) (Table 1). In addition, a total of 39 ticks belonging to 3 species (H. longicornis, H. formosensis, and I. nipponensis) were collected from vegetation by tick drag. H. flava had the broadest host range (n=7), followed by H. longicornis (n=5), A. testudinarium (n=2), I. nipponensis (n=2), and H. japonica (n=1) (Table 2). A. testudinarium was collected only from the wild boar (6 ticks) and Eurasian badger (1), while I. nipponensis was collected from water deer (4) and raccoon dog (1) and by tick drag (6). H. longicornis and/or H. flava were collected from all animal hosts, while H. japonica (1 tick) was collected only from domestic dogs (Table 2).

Excluding the wild boar, Eurasian badger, and ring-necked pheasant, which were collected only once, the highest TI was observed for domestic dogs (29.6) (Table 2). For wild mammals, the highest TI was observed for Siberian roe deer (17.4), followed by water deer (14.4) and raccoon dogs (1.3). H. longicornis nymphs (160, 39.8%) and larvae (156, 38.8%) were collected more frequently than adults (86, 21.4%) (Table 3). In contrast, H. flava adults (103, 65.2%) were more commonly collected than nymphs (20, 12.7%) and larvae (35, 22.2%).

DISCUSSION

In our study, H. flava had the broadest host range, followed by H. longicornis, A. testudinarium, I. nipponensis, and H. japonica. By contrast, in a previous survey of wild mammal hosts, 70 I. nipponensis were collected from water deer, Siberian roe deer, and 3 other mammalian species, whereas only 1 H. japonica was collected from a water deer, and no A. testudinarium was collected from any of the mammals examined [10].

The highest TI was observed for domestic dogs, some of which seemed to be exposed to tick habitats of tall grasses and forested areas. For wild mammals, the highest TI was observed for Siberian roe deer, followed by water deer and raccoon dogs. In a separate study, the raccoon dog demonstrated a very high TI (38.0), while similar TIs were observed for water deer (16.4) and Siberian roe deer (9.0) [10]. Variability in observed TIs is likely due to differences in sample sizes, areas surveyed, and dates of collection.

Similar to other studies, H. longicornis was the predominant tick collected from wild and domestic animals in the ROK [10,11]. I. nipponensis was infrequently collected in this study; however, it is the primary tick collected from small mammals [10,12] and has been implicated in the transmission and maintenance of tick-borne pathogens to humans in the ROK [10,12,13,14,15,16].

One adult female H. formosensis was first collected from vegetation by tick drag on Mara Island, Seogwipo-si, Jeju-do, a migratory bird stopover island during their spring and fall migration to breeding and feeding grounds, respectively. H. formosensis nymphs were reported from neighboring countries and also was collected from migratory birds during 2010-2012 [17]. Further investigation need to be conducted to determine if H. formosensis has become established on the island and, if so, how well it adapted there or other places.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institute of Biological Resources (2012). This project was partially funded by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response Systems (AFHSC-GEIS) and BK21 PLUS Program for Creative Veterinary Science Research, Research Institute for Veterinary Science and College of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University. The authors sincerely appreciate Prof. H. B. Lee, Prof. K. J. Na, Prof. S. C. Yeon, Dr. C. Y. Choi, Mr. Y. J. Kim, and Mr. S. H. Kim for providing ticks collected from domestic and wild animals.

Notes

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.