Bronchopulmonary Infection of Lophomonas blattarum: A Case and Literature Review

Article information

Abstract

Human infections with Lophomonas blattarum are rare. However, the majority of the infections occurred in China, 94.4% (136 cases) of all cases in the world. This infection is difficult to differentiate from other pulmonary infections with similar symptoms. Here we reported a case of L. blattarum infection confirmed by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid smear on the microscopic observations. The patient was a 21-year-old female college student. The previous case which occurred in Chongqing was 20 years ago. We briefly reviewed on this infection reported in the world during the recent 20 years. The epidemiological characteristics, possible diagnostic basis, and treatment of this disease is discussed in order to provide a better understanding of recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of L. blattarum infection.

INTRODUCTION

Lophomonas blattarum is a protozoan that usually parasitizes in the intestinal tracts of termites and cockroaches; Lophomonas belongs to the supergroup Excavata, first rank Parabasalia, and second rank Cristamonadida in protozoa [1]. It can cause infections in a variety of tissues and organs, including the maxillary sinus and other sinuses, lungs, reproductive system, and respiratory tract. This infection is difficult to differentiate from other common infections with similar symptoms (such as pneumonia, bronchitis, or inflammation) from the clinical manifestations and laboratory tests. Drugs for other common infections were almost useless for L. blattarum infection [2,3]. Two-thirds of the patients have been diagnosed with L. blattarum infection as soon as they were admitted to the hospital, then they were given metronidazole or tinidazole for treatment. The other one-third of patients was treated with antibiotics without effects. Early and correct diagnosis is a key factor for treatment of L. blattarum infection.

This protozoan parasite was identified by bronchoscopic brush smears, bronchoscopic biopsy smears, or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and the patient was treated with metronidazole or tinidazole, with good prognosis. So far, L. blattarum human infections occur mainly in China, in addition to 6 cases from Peru in the National Reference Center of Pediatric Diseases of Lima from 2009 to 2010 [4], 2 cases from Spain [5,6], and 1 case of L. blattarum isolated from a clinically normal houbara bustard in the United Arab Emirates in 1999 [7].

In China, since the first case of pulmonary L. blattarum infection was reported in 1993 [8], 136 cases have been diagnosed during the recent 20 yeas [2,3,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] (Table 1). Among the 136 cases, more than 3 quarters were identified in the southern area of China. There was only 1 case which was reported so far on the basis of available information in Chongqing but checked out in Shanghai in 2000 [31]. Here, a new case of L. blattarum infection was found in Chongqing, which was identified in the University-Town Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in 2013. Also, a literature review of L. blattarum infection in China during the recent 20 years has been carried out in order to provide a better understanding of recognition and diagnosis of L. blattarum infection.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 21-year-old female college student was admitted to the University-Town Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, on 21 June 2013, with chief complaints of cough and expectoration for 3 days accompanied with fever for 2 days without any past or family history. Three days ago, she caught a cold followed by expectorating white phlegm along with sore throat, and the body temperature was up to 39℃ before 1 day ago. She was diagnosed as pneumonia on the chest X-ray in another hospital.

On 22 June 2013, physical examination of the patient showed both lung breath sounds rough, the bilateral lower lung auscultation with rales or rhonchi and the other vital signs included blood pressure 106/72 mmHg, pulse rate 115 beats/min, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, and body temperature 36.9℃. The clinical laboratory tests for blood, urine, feces, and hepatic and renal functions were within normal limits. However, the C-reactive protein (CRP) was 32.7 mg/L and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 22 mm/hr. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed right pleural effusions accompanied with pleural adhesions, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and the left inferior lobar inflammation. Meanwhile, she was treated with cefoxitin for anti-infection and enhancement of immunity. One day after admission, her body temperature and the pulse rate were within normal limits. However, both the rough lung breath sounds and the bilateral lower lung auscultation with rales or rhonchi were continued. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) were negative in the sputum smear, and electronic bronchoscopy was done in the left lower lobe basal segment.

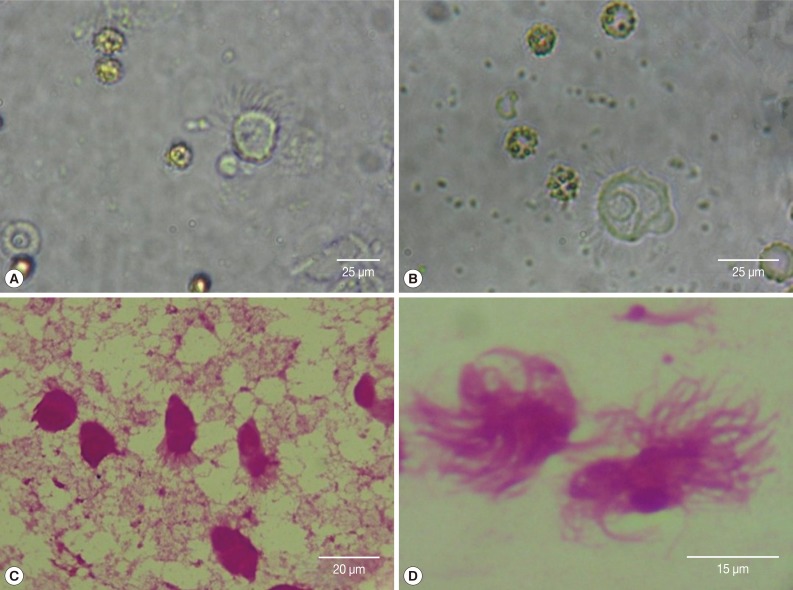

The BAL fluid was collected by bronchofiberscope, and the upper frothy sputum was spread on 4 glass slides for Wright-Giemsa stain. The live protozoan, L. blattarum, was found on light microscopy of the BAL smear. It was about 20-30 µm in size, with a round or oval-shaped body and 30-40 flagella on one end. L. blattarum can swim fast by waving its flagella constantly. After the Wright-Giemsa staining, it changed to pear-shaped, with mauve colored cytoplasm. The flagellum length was from 8 to 18 µm, arranged in bundles on one end (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

After reviewing the literature [2,3,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], we found 136 cases of previous reports of L. blattarum infections that had occurred in 11 provinces and 2 municipalities in China since 1993. Among the patients, 80 cases were male and 55 cases were female, besides 1 with unknown gender, with ages ranging from 9-days to 95 years-old. It was shown that the infection had no significant differences by gender and age. The occurrence of patients from the southern China area was 76.5% and the others came from the northern area. The southern China refers to Hunan, Anhui, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Fujian province, and Chongqing municipality. The northern China refers to Shaanxi, Liaoning, Shandong, Hebei, Xinjiang province, and Tianjin municipality). The weather of southern area is warmer and more humid.

As a part of the reported cases was identified without giving the pest species only to families, it could be called 'hypermastigote' in many databases (now called Cristamonadida [1]). We detected the patients infected with 'hypermastigote' or L. blattarum as the search keyword in VIP-database, CNKI, Wanfang-database (the 3 major databases in China), PubMed database, Embase database and the Web of Science database retrieved all the reports in recent 20 years. After rechecking and screening, 136 cases were determined. Their clinical features were listed below (Table 2).

Review of clinical and radiological analysis of 136 cases of Lophomonas blattarum infection (1993-2013)

The diagnostic clues of L. blattarum infection are as follows: First, patients have clinical symptoms of an infection without the effect of anti-infection treatment with a marked peripheral blood eosinophilia. Second, patients have underlying diseases and treated with immunosuppressants for a long time or with the pulmonary infection after surgery. Third, the X-ray and CT imaging features of the patients show ground-glass opacity, patchy consolidation, and patchy or streaky shadows distributed in bilateral lungs. Forth, the detection of L. blattarum can be done in sputum smears, bronchoscopy biopsy smears, or BAL. All the reported cases in China confirmed that the treatment of the infection depends on metronidazole and tinidazole.

L. blattarum was proved to parasitize in the colon of cockroaches [40]. Although L. blattarum usually parasitizes in intestinal tracts of termites and cockroaches, it could be discharged being accompanied with the secretion and excrement of the host's digestive tract. The cysts of this protozoa are spread by contaminated food and clothing. Therefore, someone could be infected easily by breathing the dust containing L. blattarum. To prevent L. blattarum infection, it is needed to control the source of infection, that is, termites and cockroaches. In fact, human infections with L. blattarum are relatively rare. In the past 2 decades, 136 cases of L. blattarum infection, including 2 disputable cases have been reported in China [41]. The patients reported from southern cities accounted for three-quarters. It is most likely because cockroaches and termites are the hosts of L. blattarum, this protozoan can breed easily in the humid environment.

So far, except for the 136 cases being concentrated in China, L. blattarum infection was also reported in humans in Peru in 2010 [4] and Spain in 2007 and 2010 [5,6]. There was 1 case of L. blattarum isolated from a houbara bustard that was a clinically normal bird in the United Arab Emirates in 1999 [7]. After all, 95 of 136 clinical cases which account for around two-thirds, occurred within the recent 5 years. The clinical manifestations and signs of L. blattarum infection are similar to the other etiologic pneumonia and bronchitis. It is difficult to diagnose correctly.

Two points are worthy of special mentioning: 1) ineffectiveness of antibiotics. Among the 136 patients diagnosed with L. blattarum infections, 46 patients were treated with antibiotics for anti-infection and anti-inflammatory before using metronidazole (1 patient took antibiotics for almost 3 months without effects [3]), but all invalid. 2) The influence of the underlying disease was significant. For example, 68 of 136 cases had underlying diseases (it included 3 types of diseases, 1 was the basic metabolic disorders, the other 2 were the weakened immune system and severe chronic wasting disease), mainly with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and organ transplantation which accounted for 29.4% and 30.9%, respectively. Above all, it is strongly needed to have knowledge on L. blattarum infection before giving diagnosis and treatment of this protozoan infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The research leading to this manuscript has received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31071093, 31170129, and 31200064).

Notes

We have no conflict of interest related to this study.