Abstract

The purpose of this study was to conduct a survey of Dirofilaria immitis infection among stray cats in Korea using nested PCR. We included 235 stray cats (121 females and 114 males) and evaluated each for the presence of feline heartworm infection. Blood samples were collected from 135 cats in Daejeon, 50 cats in Seoul, and 50 cats from Gyeonggi-do (Province). Of the 235 DNA samples, 14 (6.0%) were positive for D. immitis. The prevalence of infection in male cats (8/114, 7.0%) tended to be higher than that in female cats (6/121, 5.0%), but the difference was not statistically significant. In each location, 8, 2, and 4 cats were positive for infection, respectively, based on DNA testing. No significant differences in the prevalence were observed among the geographic regions, although the rate of infection was higher in Gyeonggi-do (8.0%) than Daejeon (5.9%) and Seoul (4.0%). We submitted 7 of the 14 D. immitis DNA-positive samples for sequencing analysis. All samples corresponded to partial D. immitis cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene sequences with 99% homology to the D. immitis sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. FN391553). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first survey using nested PCR to analyze the prevalence of D. immitis in stray cats in Korea.

-

Key words: Dirofilaria immitis, prevalence, nested PCR, stray cat

Dirofilariosis has been reported in many warm-blooded animals, including snow leopards [

1], coyotes [

2], ferrets [

3], cats [

4], and humans [

5]. The prevalence of feline heartworm infection is 10-20% of the prevalence in dogs within the same enzootic region [

6,

7]. Canines are a definitive host for

Dirofilaria immitis, but its life cycle can also be completed in cats [

8]. The natural resistance of cats to

D. immitis and variations in mosquito feeding preferences partly explains the lower prevalence of infection in cats [

9]. Additionally, the testing frequency is estimated to be 0.06% among cats, which is very low compared to 33% testing frequency in dogs [

7,

10,

11]. Previous studies have reported that adult heartworms are present in 2.1-4.9% of shelter cats at necropsy [

12,

13]. Both domestic and stray cats can be infected by

D. immitis, and 1 retrospective study showed that 25% of cats infected with feline heartworm were indoor cats. Most commonly, only 2-4 immature worms develop into adult heartworms in cats [

6]. However, extensive pulmonary injury can be caused by circulating larvae, even if they are cleared successfully or no adult worms develop [

9]. Many cats tolerate heartworm infection well, and in some, the disease is cured without intervention and without a fatal result. Nevertheless, some infected cats experience recurrent signs and symptoms of infection such as chronic cough, respiratory distress, and wheezing [

14]. Previous studies have shown that chronic bronchial damage and reduced clearance of mucus and inflammatory debris can be caused by infection with D. immitis; histopathological evidences of this manifestation have been found in

D. immitis-positive cats and healthy cats [

14,

15].

The availability of a specific and sensitive test for diagnosing heartworm infections could be helpful for managing infected cats, although the current diagnostic cost and limited treatment options prevent frequent testing [

4]. However, its importance cannot be disregarded as the presence of only 2 adult worms in the lungs can be fatal, and feline heartworm disease is an important cause of feline asthma [

16]. Commercially available antigen tests target an antigen in the reproductive tract of adult females, but false negative results occur in cases of single sex infections in males or juvenile worm infections [

9,

17]. Therefore, we used nested PCR analysis to detect

D. immitis. The purpose of this study was to conduct a survey of

D. immitis infection among stray cats in Korea using nested PCR.

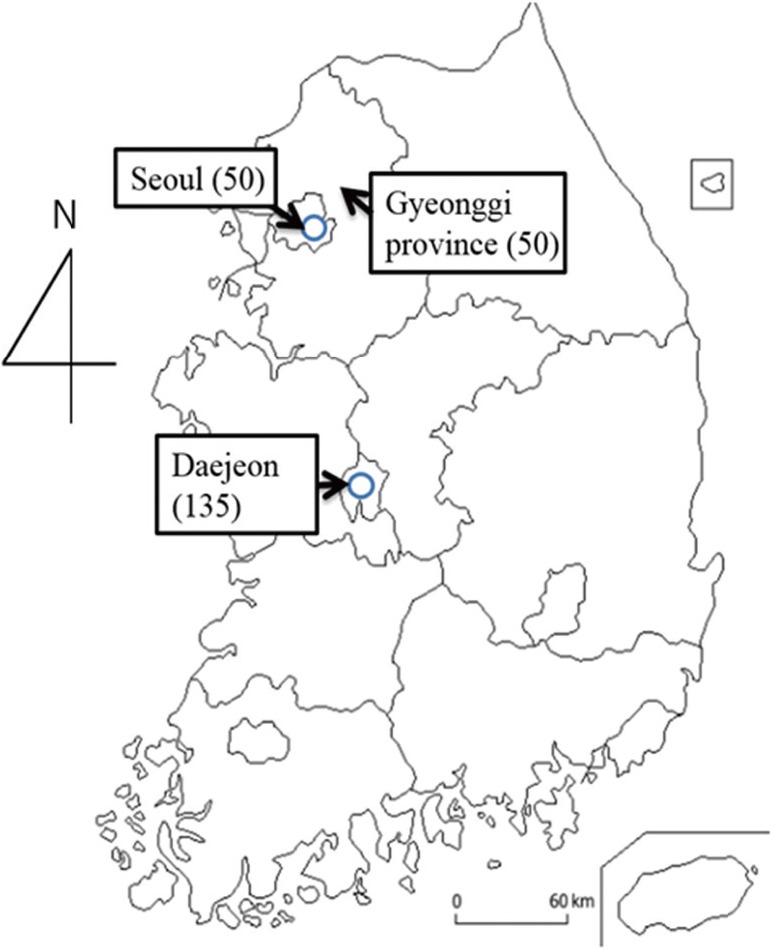

We included 235 Korean domestic short-haired stray cats (121 females and 114 males) in our study. Serum samples were obtained from 135 cats from Daejeon, 50 cats from Seoul, and 50 cats from Gyeonggi-do (Province) (

Fig. 1). The samples were randomly selected from the Daejeon, Seoul, and Gyeonggi-do regions in cooperation with local hospitals, and the sample size was unrelated to the number of stray cats by region. Blood sampling was completed in veterinary clinics and related institutions involved in veterinary medicine. The stray cats were safely captured through the local ward government's Trap, Neuter, and Return program. Female cats were subjected to ovario-hysterectomy and male cats were subjected to castration. After the procedure, the cats were returned to the territory from which they were captured. Blood was collected from each cat via cephalic or jugular puncture and separated into 2 equal samples. One blood sample was placed in a plain test tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,800 g after clotting at room temperature for 30 min. The other sample was placed in an EDTA tube for DNA extraction. None of the 235 cats showed evidence of feline leukemia virus or feline immunodeficiency virus infection using ELISA kit (SNAP test, IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, Maine, USA). This study was conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and was approved by Chungnam National University (no. CNU-00317).

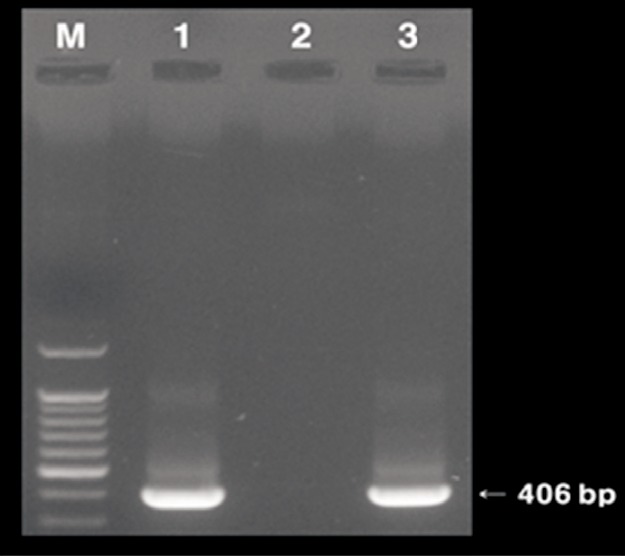

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood isolates using a PrimePrep Genomic DNA isolation kit (GeNet Bio, Daejeon, Korea), and samples were stored at 4℃ until analysis by nested PCR. The following 2 PCR primer pairs were used to amplify the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (

COI) gene [

7]: forward (5'-ATTGGTGGTTT TGGTAATTGGATGTTG-3') and reverse (5'-CAGAAGTCCCCAATACAGCAATCC-3'), which amplified a 634-bp fragment in the first round PCR and forward (5'-GGGTCCTGGGAGTAGTTGAAC-3') and reverse (5'-TTCACTAACAATCCCAAA CACCG-3'), which amplified a 406-bp fragment in the second round PCR. Nested PCR was performed using a method reported previously [

7]. The PCR products were resolved on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel in TAE buffer, and amplicons were visualized under UV light (

Fig. 2). Upon confirmation of the band of interest (406 bp), the PCR products were purified using a Gene All Elution kit (GenAll, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified PCR products were sequenced by Cosmo Genetech (Seoul, Korea). The Lasergene sequence analysis software package (DNASTAR, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) was used to edit DNA sequences. The statistical analysis was performed with the commercially available IBM/SPSS Statistics 18.0.0 computer based software program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences in the prevalence of infected cats by gender and region were analyzed by the chi-square test for independence, and Fisher's exact test, respectively. Statistical significance was defined at

P<0.05.

A nested-PCR-positive band was detected at 406 bp by electrophoresis (

Fig. 1). Of the 235 DNA samples, 14 (6.0%) were positive for

D. immitis (

Table 1). The prevalence of infection in male cats (8/114, 7.0%) tended to be higher than that in female cats (6/121, 5.0%), but the result was statistically not significant. Additionally, no significant differences were observed among the prevalence by geographic areas, although the rate of

D. immitis-positive samples was higher in Gyeonggi-do (4/50, 8.0%) than in Daejeon (8/135, 5.9%) and Seoul (2/50, 4.0%). In Korea, Liu et al. [

18] reported that the prevalence of feline heartworm infection in Gyeonggi-do, as tested by a commercially available ELISA kit and PCR analysis, was 2.6%. In the present study, 8.0% (4/50) of the cats were positive for

D. immitis, according to the nested PCR analysis. The D. immitis-positive rate was 8.7% (2/23) in female cats and 7.4% (2/27) in male cats in Gyeonggi-do, but no significant differences were noted, which agreed to the findings of Lie et al. [18]. The

D. immitis-positive rate in Gyeonggi-do was higher in the current study (8.0%, 4/50), compared to that of Liu et al. [

18]. This was likely due to the different sample areas. Liu et al. [

18] included the northern area of Gyeonggi-do, and we included the southern area. No significant differences were observed related to the geographic area or prevalence, but Gyeonggi-do was the most feline heartworm endemic area among the 3 sample locations. One retrospective study reported that the relative prevalence of feline heartworm, as compared to other feline infectious diseases, including feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus, deserves attention of clinicians [

10]. All 235 cats in the present study showed negative results for feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus using a commercially available ELISA kit.

We performed a sequencing analysis of 7 of 14 (3 from Daejeon, and 2 each from Seoul and Gyeonggi-do) D. immitis-positive samples. All sequencing samples corresponded to partial D. immitis COI gene sequences with 99% homology to a D. immitis sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. FN391553). We deposited the 7 partial sequences that showed 99% homology to each other and to the corresponding COI gene of D. immitis (accession nos. KF918393, KF918394, KF918395, KF918 396, KF918397, KF918398, and KF918399).

Feline heartworm disease is a clinical and diagnostic challenge in veterinary medicine [

18]. Commercially available ELISA tests target an antigen in the reproductive tract of adult females; therefore, false negative results can occur in cases of single sex infections in males or juvenile worm infections [

9,

17]. Positive antibody test results indicate a history of exposure to heartworm larvae in at least the L4 stage, but it cannot assess the current stage of

D. immitis infection [

18]. As little as 10 pg of

D. immitis genomic DNA can be detected using PCR; therefore, nested PCR may be a more useful diagnostic tool to detect the

D. immitis low infection in feline heartworm disease [

18]. As one of the important feline respiratory diseases, feline heartworm infection should be evaluated routinely in clinics.

This is the first survey using nested PCR to analyze the prevalence of D. immitis and to perform sequencing analysis in stray cats in Korea. Further studies are needed to characterize and compare the infectious pathways between stray cats and stray dogs.

Notes

-

We have no conflict of interest related to this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by funding (4847-302-210-13.2013) from the Korea National Institute of Health, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1. Murata K, Yanai T, Agatsuma T, Uni S. Dirofilaria immitis infection of a snow leopard (Uncia uncia) in a Japanese zoo with mitochondrial DNA analysis. J Vet Med Sci 2003;65:945-947.

- 2. Sacks BN, Caswell-Chen EP. Reconstructing the spread of Dirofilaria immitis in California coyotes. J Parasitol 2003;89:319-323.

- 3. McCall JW. Dirofilariasis in the domestic ferret. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 1998;13:109-112.

- 4. Dunn KF, Levy JK, Colby KN, Michaud RI. Diagnostic, treatment, and prevention protocols for feline heartworm infection in animal sheltering agencies. Vet Parasitol 2011;176:342-349.

- 5. Theis JH, Gibson A, Simon GE, Bradshaw B, Clark D. Case report: unusual location of Dirofilaria immitis in a 28-year-old man necessitates orchiectomy. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;64:317-322.

- 6. Genchi C, Venco L, Ferrari N, Mortarino M, Genchi M. Feline heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection: a statistical elaboration of the duration of the infection and life expectancy in asymptomatic cats. Vet Parasitol 2008;158:177-182.

- 7. Turba ME, Zambon E, Zannoni A, Russo S, Gentilini F. Detection of Wolbachia DNA in blood for diagnosing filaria-associated syndromes in cats. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2624-2630.

- 8. Nelson CT. Dirofilaria immitis in cats: anatomy of a disease. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2008;30:382-389.

- 9. Lee AC, Atkins CE. Understanding feline heartworm infection: disease, diagnosis, and treatment. Top Companion Anim Med 2010;25:224-230.

- 10. Lorentzen L, Caola AE. Incidence of positive heartworm antibody and antigen tests at IDEXX Laboratories: trends and potential impact on feline heartworm awareness and prevention. Vet Parasitol 2008;158:183-190.

- 11. Labarthe N, Serrão ML, Melo YF, de Oliveira SJ, Lourenco-de-Oliveira R. Mosquito frequency and feeding habits in an enzootic canine dirofilariasis area in Niterói, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1998;93:145-154.

- 12. Levy JK, Snyder PS, Taveres LM, Hooks JL, Pegelow MJ, Slater MR, Hughes KL, Salute ME. Prevalence and risk factors for heartworm infection in cats from northern Florida. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2003;39:533-537.

- 13. Carleton RE, Tolbert MK. Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis and gastrointestinal helminths in cats euthanized at animal control agencies in northwest Georgia. Vet Parasitol 2004;119:319-326.

- 14. Garcia-Guasch L, Caro-Vadillo A, Manubens-Grau J, Carretón E, Morchón R, Simón F, Kramer LH, Montoya-Alonso JA. Is Wolbachia participating in the bronchial reactivity of cats with heartworm associated respiratory disease? Vet Parasitol 2013;196:130-135.

- 15. Wooldridge AA, Dillon AR, Tillson DM, Zhong Q, Barney SR. Isometric responses of isolated intrapulmonary bronchioles from cats with and without adult heartworm infection. Am J Vet Res 2012;73:439-446.

- 16. Côtĕ E, MacDonald KA, Meurs KM, Sleeper MM. Feline Cardiology. Iowa, USA. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011, pp 353-363.

- 17. Berdoulay P, Levy JK, Snyder PS, Pegelow MJ, Hooks JL, Tavares LM, Gibson NM, Salute ME. Comparison of serological tests for the detection of natural heartworm infection in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:376-384.

- 18. Liu J, Song KH, Lee SE, Lee JY, Lee JI, Hayasaki M, You MJ, Kim DH. Serological and molecular survey of Dirofilaria immitis infection in stray cats in Gyunggi province, South Korea. Vet Parasitol 2005;130:125-129.

Fig. 1Areas surveyed (number) for Dirofilaria immitis infection in stray cats in Korea.

Fig. 2The specific amplified 406 bp product of feline heartworm DNA using nested PCR analysis shown in the present study (lane 1, positive control; lane 2, negative control; lane 3, positive sample). The positive control was COI gene extracted from Dirofilaria immitis worms, and the negative control was pure distilled water.

Table 1.Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis infection by nested PCR in stray cats

Table 1.

|

Daejeon city

|

Seoul city

|

Gyeonggi province

|

Total

|

|

Total number |

Positive sample |

Positive rate (%) |

Total number |

Positive sample |

Positive rate (%) |

Total number |

Positive sample |

Positive rate (%) |

Total number |

Positive sample |

Positive rate (%) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Femles |

72 |

3 |

4.2 |

26 |

1 |

3.8 |

23 |

2 |

8.7 |

121 |

6 |

5.0 |

|

Males |

63 |

5 |

7.9 |

24 |

1 |

4.2 |

27 |

2 |

7.4 |

114 |

8 |

7.0 |

|

Total |

135 |

8 |

5.9 |

50 |

2 |

4.0 |

50 |

4 |

8.0 |

235 |

14 |

6.0 |