Recurred Sparganosis 1 Year after Surgical Removal of a Sparganum in a Korean Woman

Article information

Abstract

Sparganosis, an infection due to the plerocercoid of Spirometra erinacei, are found worldwide but the majority of cases occur in East Asia including Korea. This report is on a recurred case of sparganosis in the subcutaneous tissue of the right lower leg 1 year after a surgical removal of a worm from a similar region. At admission, ultrasonography (USG) of the lesion strongly suggested sparganosis, and a worm was successfully removed which turned out to be a sparganum with scolex. Since sparganum has a variable life span, and may develop into a life-threatening severe case, a patient once diagnosed as sparganosis should be properly followed-up for a certain period of time. Although imaging modalities were useful for the diagnosis of sparganosis as seen in this case, serological test such as ELISA should also be accompanied so as to support the preoperative diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Among the parasitic infections, sparganosis is a relatively rare parasitic infection caused by the migrating plerocercoid (=sparganum) of Spirometra erinacei. Sparganosis is found worldwide but the majority of cases occur in East Asia, including Korea [1,2]. Human sparganosis was first reported in China by the discovery of ribbon-like worm bodies from a dead human body [3]. In Korea, sparganosis was first discovered from the leg of a farmer in 1917 [3]. Four years previously, we reported a sparganosis case from which a sparganum was surgically removed from the ankle region of a 60-year-old woman who was presumed to be infected by ingestion of infected copepods [4,5]. However, sparganosis recurred in the same patient after 1 year. The present report deals with the recurred sparganosis case in the subcutaneous tissue of the right lower leg.

Although the majority of sparganosis does not make critical problems, they are sometimes misunderstood as other clinical situations that make soft tissue masses. Sparganum may invade the vital organs such as the brain, and Korea in one of the countries which shows the highest number of sparganum cases. Furthermore, sparganum can survive for a long time in the human body [6-8], and the sparganum of the previous case (the same patient as in this report) was presumed to have survived for at least 20 years inside the patient's leg [4]. Therefore, possible suggestions for follow-up of sparganosis were discussed.

CASE RECORD

In our previous case report, a 60-year-old woman who had been living as a farmer in Cheonan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea, was admitted to Dankook University Hospital due to a painful nodular mass at the right ankle [4]. A sparganum was surgically removed from the ankle, and the diagnosis was sparganosis. Since she denied ingesting snake or frog meat, untreated mineral water from a local mountain was suggested to be the infection source. While she was followed up after the operation, she (61-year-old) complained of discomfort in the region superior to the right lateral malleolus with a feeling that something is moving inside her leg from 1 year after the surgical treatment.

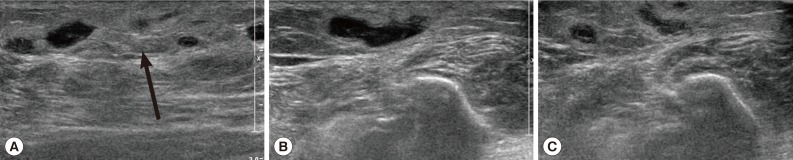

Routine laboratory tests were unremarkable, and no eosinophilia was noted. Ultrasonography (USG) showed diffuse longitudinal (about 10 cm) thickening of the subcutaneous fat layer with increased echogenicity on the lateral aspect of the right fibula (Fig. 1A). The subcutaneous thickening was located around the region where the Achilles tendon of the right lower leg begins. A long tubular structure with a diameter of 3-5 mm was found inside the subcutaneous thickening (Fig. 1B). The tubular structure was mostly continuous without interruption and partially filled with echogenic material (Fig. 1B). The anteroinferior aspect of the lesion was isolated tubular-shaped whereas the posterosuperior aspect was a tubular cystic lesion having a blind loop (Fig. 1C). These findings could be interpreted as partially thrombosed venous structure surrounded by thrombophlebitic inflammatory changes. However, in this case, venous structures of the lesion were normal and accompanied by an isolated cystic lesion. Thus, this case was suggested as a recurred sparganosis by a remained plerocercoid worm or possibly due to incomplete removal of the scolex at the time of the previous operation.

Ultrasonography of the right ankle in the present case. (A) The increased echogenicity was seen on the lateral aspect of the right fibula. Arrow indicates the soft tissue swelling. (B) A long tubular structure with a diameter of 3-5 mm was seen inside the subcutaneous thickening. The tubular structure was mostly continuous without interruption and partially filled with echogenic material. Arrows indicate the sparganum. (C) The posterosuperior aspect was tubular cystic lesion having blind loop.

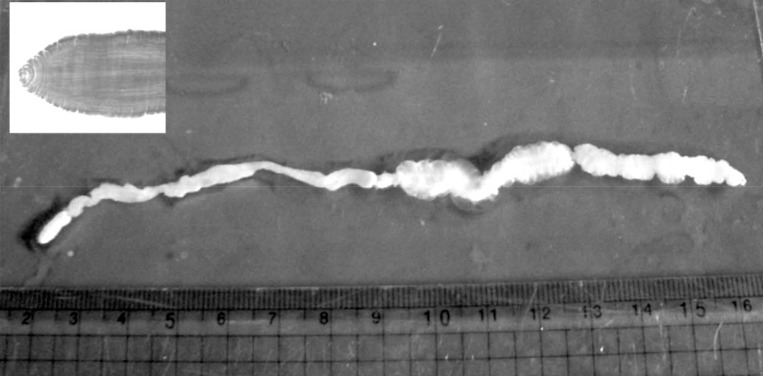

During the surgery, a longitudinal incision was made on the lateral aspect of the right lower leg. A soft, movable, and poorly marginated mass with a diameter of 2 cm was observed. The same as the previous operation, a white-shiny, synovium-like piece of body popped out through the incision, and determined as a sparganum. The removed worm was 15 cm in length, slightly shorter than that of the previously removed one (18 cm in length), and the scolex was easily seen (Fig. 2). After removing the sparganum, neuroraphy was performed because a ruptured sural nerve was observed. The pathological examination revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with a degenerating parasite caused by a parasitic (possibly sparganum) infection. The patient's symptoms were improved thereafter and considered not reappeared again for more than 2 years after the second operation.

DISCUSSION

This case is on a sparganosis case that recurred in the leg of a woman. There exists a strong gender preference with regard to sparganosis especially in Korea due to the habit of eating raw reptiles among men [1,3], which might interrupt prompt diagnosis or even lead to a wrong diagnosis. However, as mentioned in our previous report [4], sparganosis can also occur through drinking copepods contaminated in impure water [9].

Various imaging tools including plain X-ray, MRI, and ultrasonography (USG) were used in the present sparganosis case. USG findings were highly useful for the differential diagnosis of sparganosis from superficial varicose veins or soft tissue tumors [10]. USG finding of sparganosis generally includes a low echogenic tubular lesion along with increased echogenicity of the surrounding tissue which comes from the sparganum itself and chronic granulomatous inflammation, respectively. In our case, USG findings were typically in accordance with the above mentioned sparganosis that can make other causes such as thrombophlebitis ruled out.

Common clinical manifestations of sparganosis are subcutaneous lumps or masses. However, sparganum can also invade other tissues or organs such as the intestine, eyes, and spine, and even can cause pericardial or pleural effusion by invading peritoneopleural cavity [20,21]. In these cases, special diagnostic tools such as pericardiocentesis or ELISA are necessary [13]. The laboratory examination of blood from the patient of this case did not show the typical eosinophilia which is one of the common signs of parasite infections. Therefore, in case of sparganosis with neither eosinophilia nor subcutaneous masses, serological test should be used as a diagnostic tool along with the imaging modalities. For example, in a case of sparganosis that presented as a recurrent pericardial effusion, the anti-sparganum specific IgG level in the serum was significantly higher than the control [14]. Furthermore, ELISA of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is also suggested as an effective diagnostic tool for cerebral sparganosis [15]. Neuroradiologic imaging is very sensitive and also provides differential features between live and degenerating spargana [16]. However, neuroradiologic imaging alone is not sufficient for a definite identification of the lesion although it can confirm the presence of a lesion in a specific site.

During the surgical procedure, neuroraphy was performed to restore a ruptured sural nerve which had been adhered to the adjacent soft tissue due to the worm. Anatomically, the sural nerve is formed by the union of the medial sural cutaneous nerve and a branch of the common peroneal nerve which are originated from the tibial and common peroneal nerve, respectively. It usually runs in the middle of the calf but this is highly variable. It also accompanies the small saphenous vein, and superficial lymphatic vessels of the lower leg also gather around here. These situations indicate the possibilities of varicose veins and even elephantiasis although only the sural nerve was affected in this case.

In general, direct removal of plerocercoids by surgical method is the treatment of choice and also provides a definite diagnosis [2], because administration of praziquantel alone has a limitation on the successful treatment [17]. Therefore, praziquantel should be an alternative treatment only in surgically unresectable case. However, if 2 or more spargana exist in a patient, complete surgical removal is practically difficult and recurrence of sparganosis should be possible by the remnant worm after a surgical removal of a sparganum. The recurrence of sparganosis in our case may have been due to a sparganum which had been left from the previous surgery which migrated through the elongated track-like structure later. However, it might also be possible that the scolex part was cut in the previous operation, retained in the lesion, and regenerated thereafter.

In about 70% of the patients, only 1 sparganum worm has been noted [18]. However, several spargana may also be involved. In a case of pulmonary sparganosis [19], plerocercoids had been surgically removed for several times from muscles and subcutaneous tissues before the development of pulmonary sparganosis. This pulmonary sparganosis case, together with other case reports and reviews on the recurrence of sparganosis, suggests strongly the importance of proper and effective following-up of patient once diagnosed as sparganosis. The patient in our case is doing well for more than 2 years after the recurrence.

Notes

We have no conflict of interest related with this report.