A Case of Cerebral Cysticercosis in Thailand

Article information

Abstract

Cysticercosis and sparganosis are not uncommon parasitic infections in the developing world. Central nervous system infection by both cestodes can present with neurological signs and symptoms, such as seizure and mass effect, including brain hernia. Early detection and accurate diagnosis can prevent a fatal outcome. Histological examinations of brain tissues can confirm the diagnosis of cerebral cysticercosis, which differs from sparganosis by the presence of a cavitated body. We report here a case of cerebral cysticercosis which has the similar clinical and imaging findings as sparganosis.

INTRODUCTION

Cysticercosis is an important parasitic infection in the developing countries. It is caused by cestodes, the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium. Humans may be either definitive hosts (adult tapeworms residing in the human intestines) or intermediate hosts (the larval stage residing in the tissues) for T. solium [1].

Humans can become an intermediate host when they either ingest cysticerci (encysted larvae) or consume eggs. Cysticerci are ingested by eating undercooked pork while eggs are usually ingested by eating contaminated foods, including uncooked or inadequately washed raw vegetables or salads [2]. When eggs reach the stomach, gastric enzymes will break down the egg wall and release larvae. The larvae penetrate the intestinal mucosa into the blood circulation and form cysticerci which can be found in any part of the body, especially central nervous system (neurocysticercosis). There are 2 main forms of neurocysticercosis [3]. One is “isolated cyst” (cysticercus cellulosae), and the other is “racemose cyst (cysticercus racemosus) [4].

We report a case of cerebral cysticercosis in Bangkok, Thailand of which imaging studies showed an atypical convoluted lesion, similar to sparganosis, another kind of cestode infection in the brain.

CASE RECORD

A 30-year old Thai female presented to the outpatient clinic with generalized tonic-clonic seizure 1 week ago. The duration of the seizure was less than 1 min. The patient passed out for 1 hr, and gained consciousness without memory deficit. There was no history of fever, vomiting, headache, or visual disturbances. No history of previous accident, drug allergy, or cancer was present. Her physical examination was normal. The brain MRI revealed a conglomeration of several small ring enhancing lesions of 1.9×1.4×1.6 cm in size, at the cortical posterior left middle frontal gyrus. Neither midline shift nor hydrocephalus was seen (Fig. 1). A chest x-ray showed an unremarkable finding. No abnormal calcification was detected by plain radiograph of the femur. Routine blood examinations showed an absence of eosinophilia, and stool examinations showed no parasites.

MRI findings of the patient. (A) Horizontal section of T1 weighted MRI of lesion with ring enhancement. (B) Sagittal section of T1W MRI. (C) T2-weighted MRI with perilesional edema.

A left frontal craniotomy was done. A greyish white cyst of about 1×2×1 cm in size filled with clear fluid and small white nodule was removed. Multiple sections studied revealed necrotic material with neutrophils, mononuclear cells, some eosinophils, surround by granulation tissues (Fig. 2A). Nearby the necrotic material, a cyst with cavitory larva of T. solium was found. There were numerous branching and duct-like invaginations (Fig. 2B). Staining with PAS (periodic acid-Schiff) revealed microvilli (Fig. 2C), while Von Kossa staining revealed calcified corpuscles (Fig. 2D).

Histopathological findings of the patient. (A) Necrotic areas with inflammation. (B) The parasite with branching internal structures. (C) Microvilli at outer membrane of the cyst. (D) Calcified corpuscles inside the parasite.

The patient was treated with albendazole for 3 weeks and was doing well at 1 month follow up. Her family denied any history of cysticercosis.

DISCUSSION

Parasitic infections of the central nervous system can share similar clinical presentations, depending on the location, size, and number of lesions, and the inflammatory responses evoked by the parasites [2,3]. Regarding cerebral infections in developing countries, the possible diagnosis of the patient with confluent ring enhancing lesion by MRI can be due to cysticercosis, sparganosis, and even tuberculoma [4].

Regarding the imaging studies, Kim et al. [5] described the features of sparganosis by MRI as widespread white matter degeneration and cortical atrophy, and mixed-signal lesions with irregular dense enhancement of central foci. Viable cysticerci can be diagnosed on MRI as cystic lesions which appear hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 with an eccentric nodule. When the cyst degenerates, fluid leaks out and creates inflammation which is seen as peripheral enhancement on MRI and CT. Also, variable degrees of edema may be seen in the surrounding tissues [6,7].

Dubey et al. [8] claimed that soft tissue cysticercosis can be seen as elongated calcification along the muscle fibers on plain radiographs and CT scan, once the larvae become a final calcified stage, but not the early stage of live cysticerci. So, a combination of MRI and ultrasonography can be confidently used to diagnose non-invasive cysticercosis in soft tissues [8].

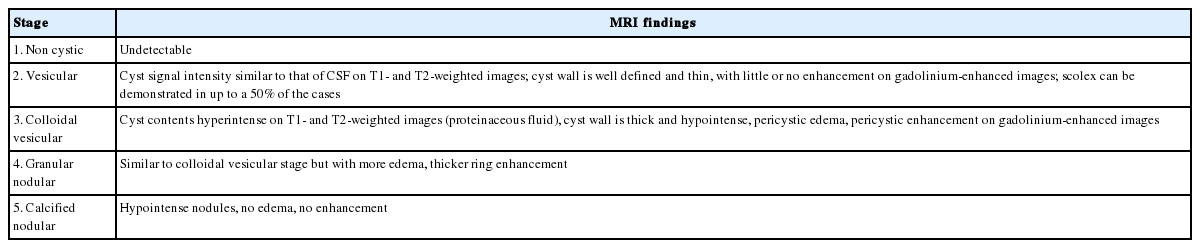

The definite diagnosis of cysticerci can be made only by tissue biopsy. Spargana differ from cysticerci by the absence of bladder walls and armed scolex and the presence of solid non-cavitated body [9]. However, in our case we could not find the scolex by histological studies. Teitelbaum et al. [10] claimed that the scolex in cysticercosis is found in nearly 50% of cases. The reason why we cannot find the scolex is related to “stages of the disease”. According to the stage of the cyst, our case was compatible with “colloidal vesicular stage”, in which larvae begin to degenerate and scolex disintegrates, with surrounded striking inflammatory responses as shown in Table 1 [11,12].

Recently, there is a PCR technique which can help molecular genetic confirmation [13]. Unfortunately, we lack molecular facilities in our center. We hope that we will have a chance to investigate more in the future.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We do not have any conflict of interest related to this work.