Identification of Cystoisospora ohioensis in a Diarrheal Dog in Korea

Article information

Abstract

A 3-month-old female Maltese puppy was hospitalized with persistent diarrhea in a local veterinary clinic. Blood chemistry and hematology profile were analyzed and fecal smear was examined. Diarrheal stools were examined in a diagnostic laboratory, using multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) against 23 diarrheal pathogens. Sequence analysis was performed using nested PCR amplicon of 18S ribosomal RNA. Coccidian oocysts were identified in the fecal smear. Although multiplex real-time PCR was positive for Cyclospora cayetanensis, the final diagnosis was Cystoisospora ohioensis infection, confirmed by phylogenetic analysis of 18S rRNA. To our knowledge, this the first case report of C. ohioensis in Korea, using microscopic examination and phylogenetic analysis.

INTRODUCTION

In humans, cyclosporiasis and cystoisosporiasis are frequently associated with immunocompromised patients worldwide [1]. Recently, canine cyclosporiasis and cystoisosporiasis have been reported. Cyclospora cayetanensis is considered an important pathogen in humans and vertebrates since human cyclosporiasis was first identified in diarrheal patients from Papua New Guinea [2]. The genus Cyclospora comprises obligate intracellular coccidian protozoa that reside in the intestinal epithelium and bile duct of hosts [2]. C. cayetanensis is transmitted through water-borne, soil-borne, and food-borne routes in developing and developed countries [2]. To date, Cylospora-like organisms or C. cayetanenensis have been detected in dairy cattle, Macaca mulatta rhesus monkey, wild chicken, and dogs [2].

Cystoisospora canis, C. ohioensis, and C. burrowsi cause diarrhea in puppies <6 months of age and immunocompromised dogs [3]. Although C. canis is the prevalent Cystoisospora species in dogs, C. ohioensis is frequently detected in Chinese dogs [4]. Recently, Japanese raccoon dogs were identified as the reservoir host of C. ohioensis [5]. However, no clinical cases of canine cystoisosporiasis have been reported to date in Korea although experimental infection and sporulation of C. ohioensis isolates have been performed in Korean puppies [6].

It is difficult for veterinary clinicians to diagnose cyclosporiasis and cystoisosporiasis based on clinical signs alone. The morphological similarity of Cyclospora and Cystoisospora oocyst hinders microscopic diagnosis using stools. Thus, both microscopic examination and molecular techniques for differential diagnosis are used [4,5]. The present study aimed to describe a clinical case in which the protozoan pathogen C. ohioensis was identified in a Korean dog, using microscopy of diarrheal stools and confirmed using phylogenetic analysis of 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

CASE RECORD

A 3-month-old female Maltese puppy was hospitalized with mild to moderate symptoms of repetitive diarrhea, dehydration, and reduced appetite in a local veterinary clinic. Microscopic examination of fecal smear was performed. Blood chemistry and hematology profile were analyzed using the Fuji DRI-CHEM NX500 automated clinical chemistry analyzer (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan) and veterinary hematology analyzer PE-6800 VET (Prokan, Shenzhen, China), respectively.

Blood chemistry analysis showed that total protein and sodium concentrations were slightly lower than the normal range (Table 1). Because vomiting and diarrhea lead to decreased total protein and sodium concentrations, these results were consistent with the observed symptoms. In contrast, the concentration of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (484 U/L) was higher than the normal concentration. Although high ALP concentration is associated with hepatic damage, it is frequently observed in normal puppies. Total white blood cells and red blood cells were in the normal range. Remarkably, the number of lymphocytes and neutrophils were 6.7×103/μl and 6.6×103/μl, respectively. The percentage of lymphocytes and neutrophils were 47.6% and 47.5%, respectively.

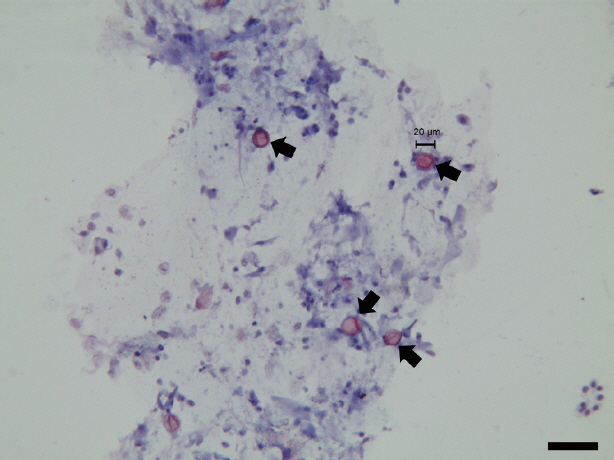

Fecal smears fixed with 3% acid alcohol were stained with boiling safranin and counter-stained with hematoxylin. The microscopic image was acquired and analyzed by LAS V4.1 software (Leica Microsystems, Frankfurt, German). Phase-contrast microscopy showed that the fecal smears were negative for spirochetes. Coccidian oocysts were clearly observed in the fecal smears (Fig. 1). All oocysts were 20 to 22 μm in diameter, with an oval structure, and appeared refractile. The oocysts were stained red, with more intense staining at the edges than at the center. However, because the internal structure of the oocysts was not clearly determined, the genus of the pathogen could not be confirmed based on microscopic morphology.

Diarrheal stools were collected and transported to POBANILAB, an animal hospital specialized in infection and allergy diagnostics. Immunochromatographic assay, multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) were performed at POBANILAB using POBGEN canine enteric pathogen detection kits (POSTBIO, Hanam, Korea) for 23 enteric pathogens, including canine distemper, parvovirus, coronavirus, norovirus, circovirus, astrovirus, sapovirus, group A rotavirus, Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Salmonella species, entero-toxigenic Escherichia coli, enteropathogenic E. coli, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, enteroinvasive E. coli, Lawsonia intracellularis, Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, C. cayetanensis, Toxoplasma gondii, and Toxocara canis. Although all laboratory tests were negative for 8 canine viruses, 9 bacteria, and 5 other parasites, multiplex real-time PCR showed a positive reaction only for C. cayetanensis. Considering that the threshold cycle value of C. cayetanensis was as high as 28.8, C. cayetanensis was suspected to be responsible for the diarrhea.

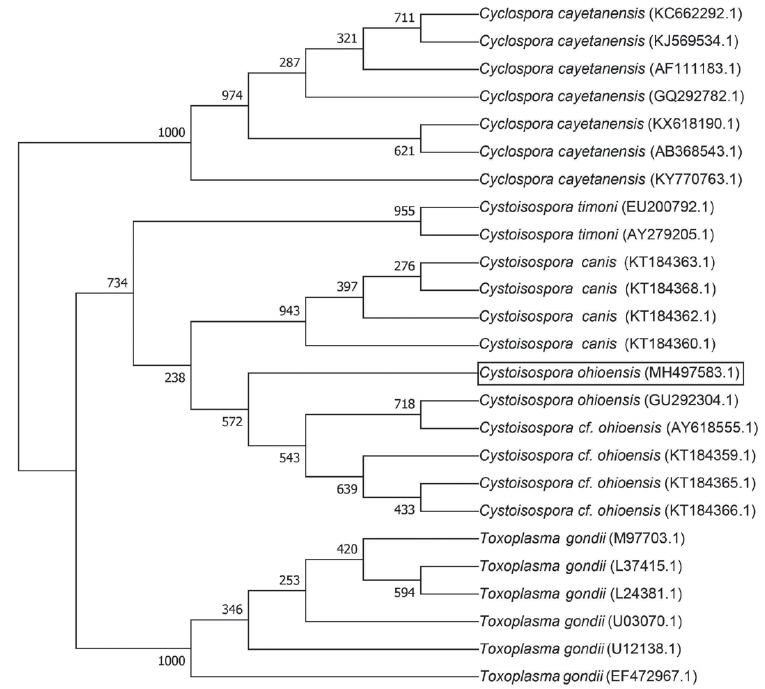

In order to confirm coccidian organisms in fecal samples, sequence analysis was performed as described previously [7]. For primary PCR, ExCycF (5′-AAT GTA AAA CCC TTC CAG AGT AAC-3′) and ExCycR (5′-GCA ATA ATC TAT CCC CAT CAC G-3′) were used to amplify 18S ribosomal RNA locus. Nested PCR was performed with NesCycF (5′-AAT TCC AGC TCC AAT AGT GTA T-3′) and NesCycR (5′-CAG GAG AAG CCA AGG TAG GCR TTT-3′). A 498-bp nested PCR product was confirmed on a 1% agarose gel and purified. The purified PCR product was cloned in competent E. coli using an All in One™ PCR Cloning Kit (Biofact, Deajeon, Korea). Sequencing was performed with ABI 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) using the Sanger dideoxy method. C. cayetanensis, C. ohioensis, C. canis, C. timonii, and T. gondii were used as outgroup species. Sequence alignment of 18S rRNA was performed using ClustalX2.1 (http://softadvice.informer.com/Clustalx_2.1.html). The phylogenetic tree was analyzed using the neighbor joining method and generated using MEGA7 (http://www.megasoftware.net/).

Sequence data of 18S rRNA obtained in this study were deposited in Genbank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Accession no. MH497583.1). Phylogenetic analysis of 18S rRNA sequence showed a 98.79% homology with the C. ohioensis sequence (GenBank Accession No. AY618555.1) (Fig. 2). However, sequence analysis did not match with any of C. cayetanensis sequences. On the basis of all data, the final diagnosis of this case was confirmed as C. ohioensis infection.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the detection of C. cayetanensis by multiplex PCR; however, the final diagnosis of this case was C. ohioensis infection, confirmed by sequence analysis. Recently, C. cayetanensis was identified in the diarrheal stools of dogs in Nepal and Brazil [1]. It has also been reported that some human cyclosporiasis cases in Guatemala, Peru, Nepal, Jordan, and Egypt may be associated with contact with C. cayetanensis-infected animals [2]. However, C. cayetanensis experimental infection in mouse, rat, sand rat, chicken, duck, rabbit, hamster, ferret, pig, dog, owl monkey, rhesus monkey, and cynomolgus monkey have failed [9]. Although zoonotic potential of C. cayetanensis seems to be low, public health guidelines emphasize on preventing its transmission from companion animals to humans. Canine cyclosporiasis has not been documented in Korea to date; however, it is necessary to monitor it in future research.

To our knowledge, this is the first phylogenetic analysis of C. ohioensis isolates confirmed in a veterinary clinic in Korea. Previous studies have reported high prevalence of canine cystoisosporiasis: 8.7% in Austria, 5.7% in north-eastern Italy, and 5.1% in the United Kingdom [3]. C. canis was the prevalent species in the United Kingdom, whereas C. ohioensis was prevalent in Australia, Japan, and China [3–5]. Although other coccidian parasites are not associated with peripheral eosinophilia, it is known that cystoisosporiasis causes eosinophilic enteritis [1]. However, veterinary clinicians could not observe peripheral eosinophilia in the hematology profile (Table 1). The veterinary hematology analyzer commonly used in Korea has only 3 channels for lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils; this limitation might hinder the diagnosis of C. ohioensis in dogs.

Notably, nested PCR primers described in a previous study [7] detected not only C. cayetanensis but also C. ohioensis because the 18S rRNA gene is frequently used to detect protozoa [4,5,7,8]. In some previous studies, 18S rRNA for C. cayetanensis and 5.8S rRNA and ITS2 region for Cystoisospora belli were used for the development of multiplex PCR, whereas in other studies, 18S rRNA and ITS1 genes of Cystoisospora spp. were used for phylogenetic analysis [4,5,8]. For diagnostic purposes, detection by the 18S rRNA gene has limitations in differentiating C. cayetanensis from C. ohioensis. Therefore, ITS1, which is a high-copy number element of the genome commonly used as a DNA biomarker or DNA barcode, could be a promising target for detecting and differentiating C. ohioensis and C. cayetanensis. After the development of C. ohioensis species-specific PCR, its primer specificity should be tested with C. cayetanensis.

Based on multiplex real-time PCR and fecal smear analyses, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and metronidazole were initially administered to the puppy for treatment of the condition tentatively diagnosed as canine cyclosporiasis. In general, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole is recommended for the treatment of cyclosporiasis and cystoisosporiasis [1]. However, an initial prescription of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole did not improve the clinical signs of this case. A combination of clavamox (amoxicillin trihydrate/clavulanate potassium) and metronidazole was effective in the treatment of diarrhea in this case. Ciprofloxacin is an alternative drug for the treatment of diarrhea in HIV-infected patients or patients allergic to sulfa drugs [1]. Recently, nitazoxanide was used in the treatment of a C. cayetanensis-infected patient who was not responsive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [10]. Although ciprofloxacin or nitazoxanide was not prescribed in this case, notably, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole was not effective. Thus, a combination of clavamox and metronidazole can be considered as an alternative treatment for canine cyclosporiasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through Advanced Production Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (316021-03-1-SB010).

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declared that there is no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.