Epidemiological Characteristics of Re-emerging Vivax Malaria in the Republic of Korea (1993–2017)

Article information

Abstract

Historically, Plasmodium vivax malaria has been one of the most highly endemic parasitic diseases in the Korean Peninsula. Until the 1970s, vivax malaria was rarely directly lethal and was controlled through the Korean Government Program administered by the National Malaria Eradication Service in association with the World Health Organization’s Global Malaria Eradication Program. Vivax malaria has re-emerged in 1993 near the Demilitarized Zone between South and North Korea and has since become an endemic infectious disease that now poses a serious public health threat through local transmission in the Republic of Korea. This review presents major lessons learned from past and current malaria research, including epidemiological and biological characteristics of the re-emergent disease, and considers some interesting patterns of diversity. Among other features, this review highlights temporal changes in the genetic makeup of the parasitic population, patient demographic features, and spatial distribution of cases, which all provide insight into the factors contributing to local transmission. The data indicate that vivax malaria in Korea is not expanding exponentially. However, continued surveillance is needed to prevent future resurgence.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is one of the oldest known and most prevalent parasitic diseases in the world, with an estimated 3.2 billion people being at risk of infection [1]. The incidence of malaria has decreased in recent years. In 2016, there were an estimated 216 million cases of malaria, about 5 million more cases than in 2015, and the number of deaths reached 445,000, a similar number to the previous year [2]. Among the protozoa that cause malaria, Plasmodium falciparum is the greatest menace because of its high mortality rate. Malaria caused by P. vivax is less lethal but is a huge burden on public health, greatly affecting the quality of life for many people in tropical, subtropical, and temperate countries [3,4]. Previous eradication programs have shown that P. vivax can persist long after P. falciparum is eliminated [5]. Unlike P. falciparum, P. vivax infections include dormant hypnozoites that can survive in the liver without the onset of disease and cause clinical relapses. These relapses manifest as blood infections that are clinically indistinguishable from primary infections. They constitute a substantial, but geographically variable, proportion of the total infections and disease risk within populations [6,7]. Moreover, parasitemia in a P. vivax infection is usually of a lower density than that in a P. falciparum infection, making diagnostic tools less effective.

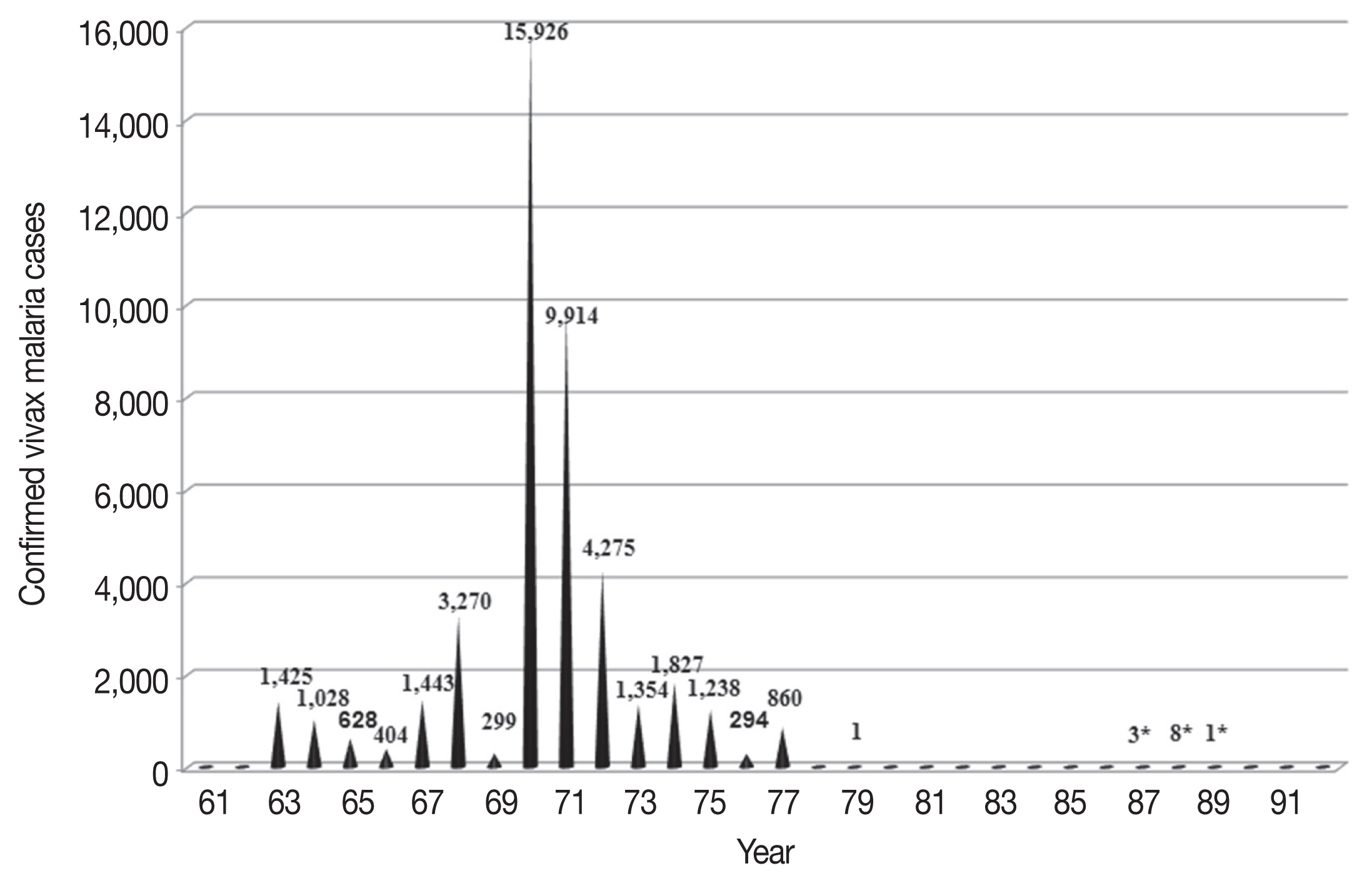

Vivax malaria has been an endemic infectious disease in the Korean Peninsula for a long time (Fig. 1). Indigenous falciparum malaria has not been reported. vivax malaria was eliminated in Korea in the late 1970s but re-emerged in the early 1990s and has continued to prevail despite the ongoing national eradication program [8,9].

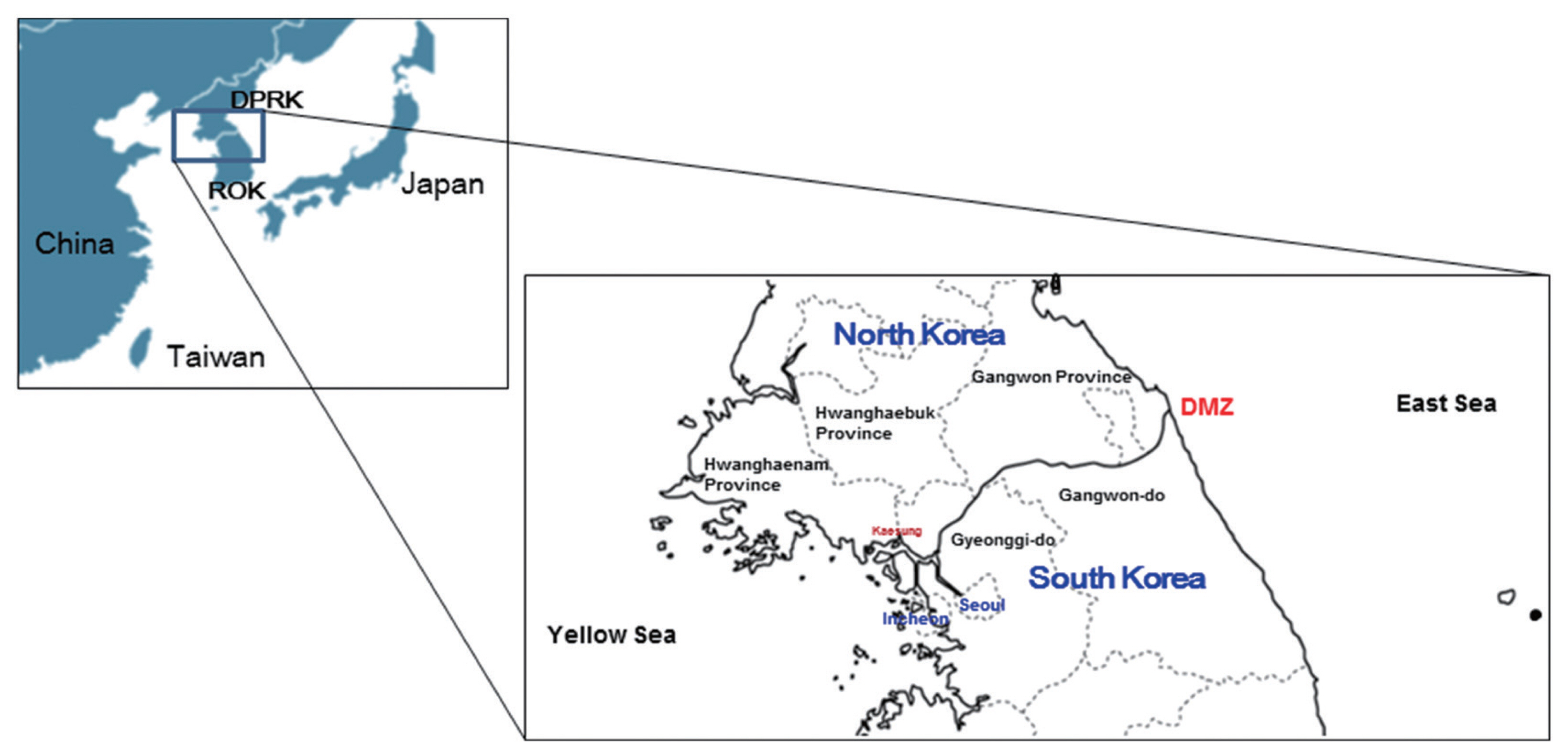

Map of the Korean Peninsula. The DMZ divides Korea and North Korea. Malaria in Korea occurs mainly in the northern area close to the DMZ of Incheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, and Gangwon-do, and malaria in North Korea occurs in Gaeseong City, North and South Hwanghae provinces, and Gangwon province.

The aim of this brief review is to provide key information on the epidemiological and biological characteristics of reemerging vivax malaria in Korea. The review focuses on the characterization of the transmission of vivax malaria in Korea after its re-emergence in 1993.

MALARIA CONTROL UP TO 1993

In Korea, malaria is classified as a group III infectious disease and malaria control efforts started in the middle of the 20th century. From the early 1970s to 1993, Korea was considered to be a malaria-free region. Historically, however, P. vivax malaria was highly endemic in the Korean Peninsula for centuries and caused unstable malaria transmission [8,9].

Malaria is popularly known as Hah-roo-geo-ri (meaning “every-other-day fever”) or Hahk-geel (Korean disease name) [10]. Medical characteristics of vivax malaria in Korea include few previous clinical malaria episodes prior to the current infection, no association with concurrent bacteremia, and extremely rare occurrences of severe anemia, hypoglycemia, and acute kidney injury complications. Mortality is rare. Relatively common and notable characteristics include cerebral and pulmonary manifestations, spontaneous bleeding, shock, and metabolic acidosis [11]. Many medical books published in the Joseon Dynasty described the main symptoms and treatments for the disease. The first systematic and scientific descriptions of malaria in the Korean Peninsula were published in 1913 [12]. The article described P. vivax cases confirmed by microscopy in the general population and stationed Japanese army soldiers. The same article also provided information on the prevalence of vivax malaria in the Korean Peninsula during the Japanese colonial era. During the Korean War (1950–1953), vivax malaria became a serious problem. Treatment of American troops infected with vivax malaria and the recurrence of the infection after repatriation were important medical issues [13,14]. Malaria control was consolidated in 1959 with the inauguration of the National Malaria Eradication Service (NMES) under the control of Korean Government with the assistance of the Global Malaria Eradication Program of the World Health Organization (WHO), which included regions of the globe other than Africa. As a part of these efforts, a nationwide survey was performed to gauge the prevalence of the protozoan parasite [15]. The use of effective insecticides and anti-malarial drugs, as well as an improved standard of living and easy access to medical clinics facilitated the effective treatment of malaria. As a consequence, the national prevalence of malaria was markedly diminished by the late 1970s (Fig. 2) [16–19]. Extensive use of agricultural pesticides also contributed greatly to the decrease in malaria incidence through the eradication of the mosquito vector of the disease. In 1979, the WHO officially certified that Korea was a malaria-free country. The country was the first nation to receive this WHO certification [20]. With the exception of a memoir citing 2 cases of malaria in 1985 [18], no official malaria cases were reported in Korea until 1993. At that time, one case was reported along the western edge of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a fortified zone 4 km wide and 248 km long that incorporates territory on both South and North Korea. The DMZ was established following the end of the Korean War by pulling back the respective forces 2 km from each side of the border (Fig. 1) [21,22].

RE-EMERGENCE OF VIVAX MALARIA

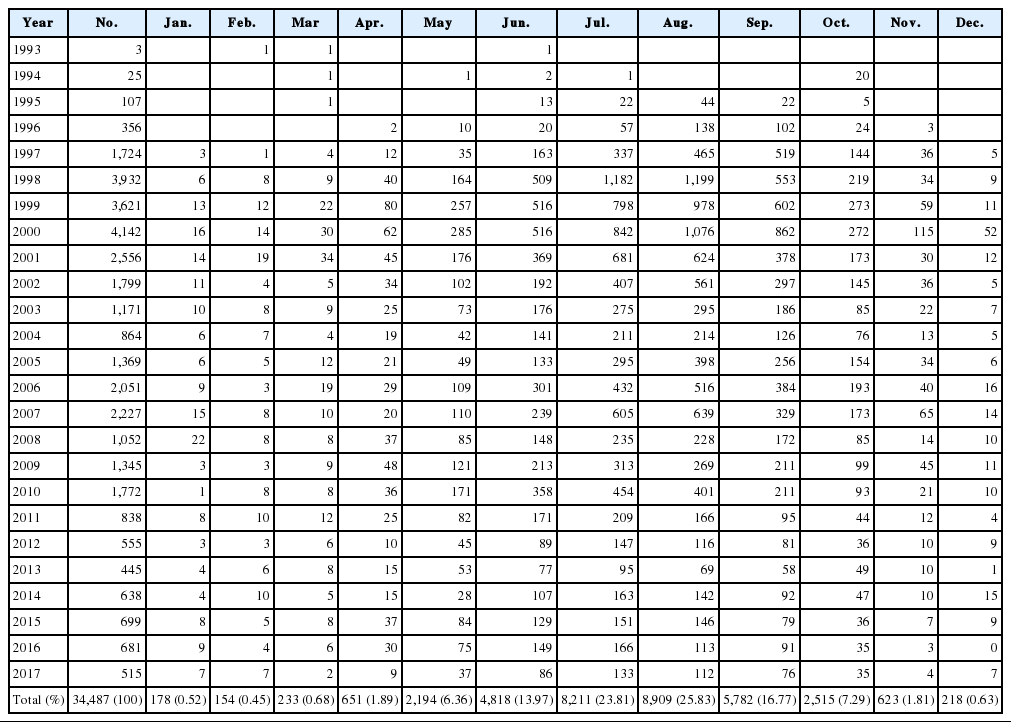

In July 1993, a Korean Army soldier stationed near the western edge of the DMZ in northern Gyeonggi-do (do=province) developed a fever with a periodic pattern of occurrence and was admitted to the Capital Armed Forces General Hospital. He was diagnosed with vivax malaria based on the blood smear method [21], which revealed the typical ring, trophozoite, and gametocyte forms of P. vivax. After this first case of recurrence, there was an exponential increase in vivax malaria cases in Korea with epidemic outbreaks from 1995–2000 (Table 1; Fig. 3). Since then, vivax malaria has been recognized as a notable public health problem [23–25].

Number and percentage of vivax malaria cases confirmed in Korea from 1993 through 2017, and the distribution of the confirmed cases according to the month

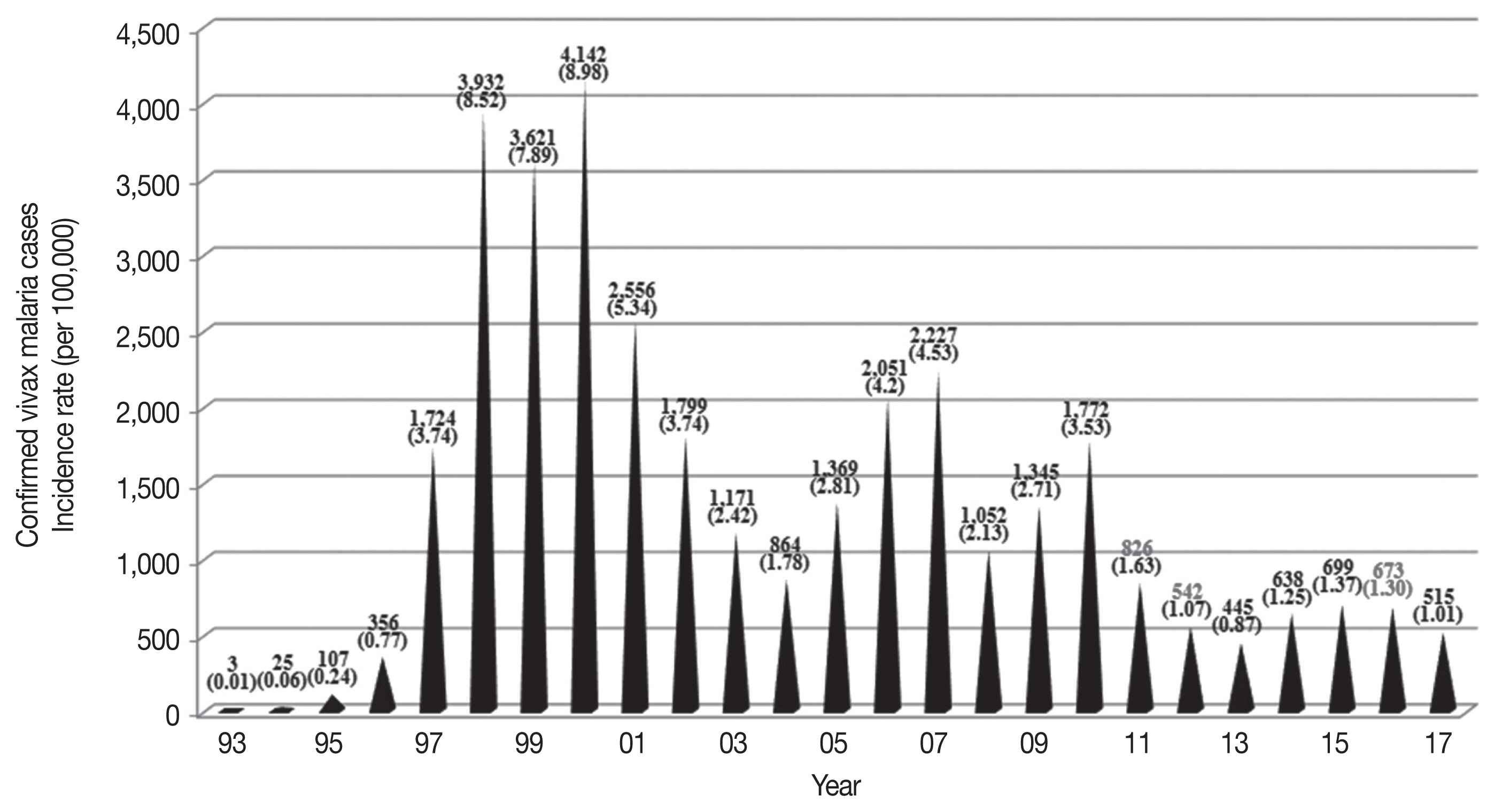

Indigenous malaria cases in Korea after re-emergence. Since its re-emerging in 1993, the highest patient outbreak occurred in 2000. Since 2000, there has been a mixed pattern of repeated increases and decreases in the incidence of malaria, but the overall trend shows a plateau.

Almost all (>90%) of malaria cases at the beginning of the outbreak occurred among Korean and American soldiers stationed near the DMZ in the northern part of Gyeonggi and Gangwon-do, and among veterans who had been repatriated to their hometowns where they subsequently developed vivax malaria [26]. Prior to 1996, over 80% of vivax malaria patients were military personnel. However, the prevalence gradually decreased from 65% in the period of 1997–2000 (8,786 of the 13,419 total cases; [27,28]) to approximately 40% in 2007 (908 of the 2,227 total cases) [29]. Correspondingly, the prevalence grew among the civilian population residing in nearby areas. Malaria has once again become endemic and a serious public health burden in Korea. The Korean Army introduced a strategy of mass chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine during the malaria transmission season and primaquine after the transmission season to reduce the number of vivax malaria cases in both the military and civilian populations. Chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine and primaquine began with about 16,000 soldiers in 1997 and was expanded to more than 200,000 military personnel in zones with a high risk for vivax malaria [30].

The increased risk of malaria infection among people near the DMZ suggested that North Korea might be a major reservoir of vivax malaria. The infection would spread across the border to Korea via sporozoite-bearing mosquitoes (Fig. 2) [31]. North Korea had a restricted capacity to eliminate malaria until 1998 and experienced its highest reported incidence of malaria in 2001, peaking at 296,540 microscopically confirmed and indigenous cases (43.4 cases per a population of 1,000), according to the 2010 WHO World Malaria Report. Malaria control efforts by North Korea for at-risk populations focused on mass primaquine preventive treatment (MPPT) as a means of chemoprophylaxis directed towards relapse, and the introduction of a National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) in 1999. Both strategies have been fully operational since 2001 [32,33]. The majority of cases in North Korea occurred in Gangwon and Hwanghae Province, which border the DMZ. Korea had over 4,000 cases reported in the 2010 WHO World Malaria Report (Table 1) [34]. High-risk areas in Korea were adjacent to those in North Korea, including Incheon-si (si=city) and northern Gyeonggi and Gangwon-do. Perhaps exacerbating the transmission, travelers from Korea were allowed to visit certain regions of North Korea, including Gaeseong City and Geumgang-san (san=mountain) (Fig. 1). The influx of mosquitoes (Anopheles sinensis) infected with P. vivax from North Korea could be one of the possible routes of re-emergence. An. sinensis, the major anopheline vector for vivax malaria in Korea, travels up to 12 km in a single night, theoretically permitting traversal of the DMZ [35]. Meanwhile, a haplotype network analysis of the parasite’s mitochondrial genome suggested that the genealogical origin of the re-emerged P. vivax in Korea was Southern China [36]. Further complex analyses of the genotypes of the Korean P. vivax population are necessary to conclusively trace the path of reemerged P. vivax in Korea.

PREVALENCE OF THE MALARIA PARASITE

The published articles included in this review chronicle the prevalence of vivax malaria between 1993 and 2017 in Korea. We incorporated data from several sources, including [1] national-level data including guidelines, reports, documents, and maps from the Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (KCDC), [2] related data from outside the Ministry of Health and Welfare, [3] scientific articles on malaria in Korea, and [4] WHO reports of technical missions, records, and reports of the WHO Regional Office for Asia meetings. In Korea, reports to the local Public Health Center (PHC) for malaria cases in hospitals or clinics are required by law. PHCs must periodically report cases to the KCDC using the infectious diseases surveillance system [37]. Since the re-emergence of vivax malaria in Korea (1993–2017), 33,972 cases have been diagnosed and reported (Table 1).

The high-risk areas in Korea adjacent to the malaria-risk areas in North Korea, which include Incheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, and Gangwon-do, account for over 70% of all vivax malaria cases in Korea (Table 2). Each malaria case in Korea is reported in the metropolitan area/province where the diagnosis is made, which may differ from the area where the infection occurred. In addition, it is particularly difficult to ascertain the transmission sites, since approximately 60% of vivax malaria in Korea is latent, with symptoms occurring 1–24 months after infection [38]. The issue of latency of vivax malaria will be discussed in later sections. Thus, despite the recent progress to reduce malaria cases, these efforts will likely not be sufficient to eliminate malaria from Korea.

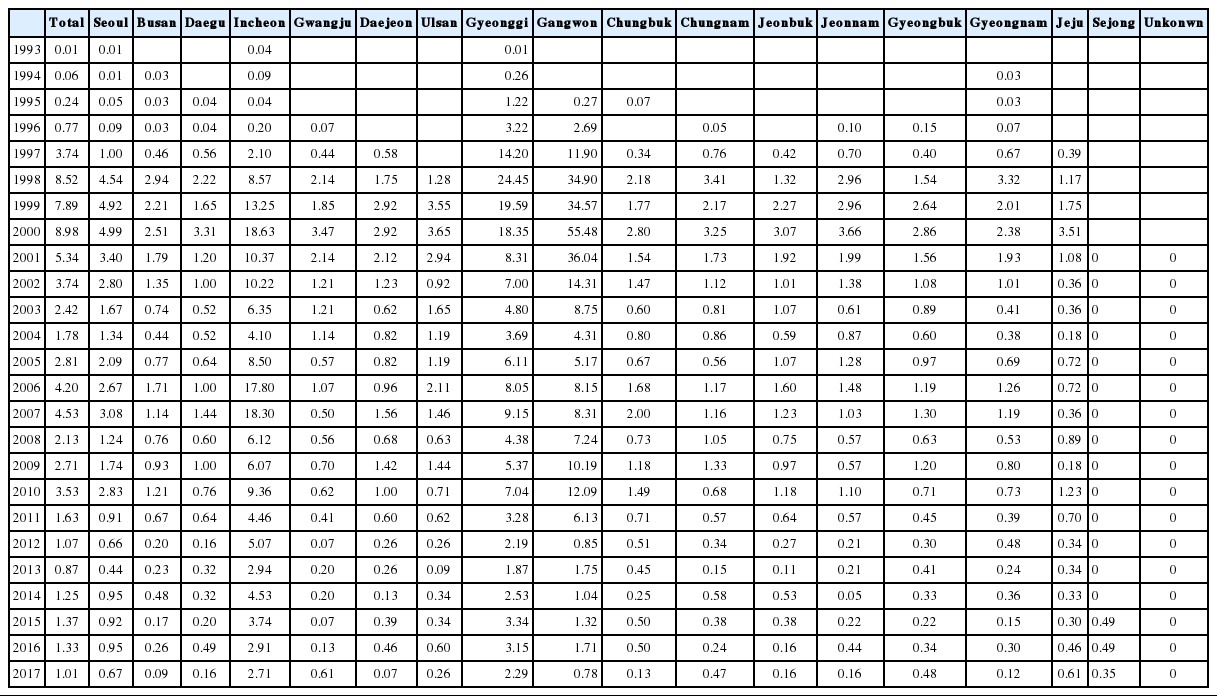

Number and percentage of vivax malaria cases confirmed in Korea from 1993 through 2017 according to the Province

The temporal frequency of cases includes 3 major peaks in 2000 (4,142 cases), 2007 (2,227 cases), and 2010 (1,772 cases) (Table 1). The overall decline in cases may reflect the dedicated anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis that has been carried out on military bases since 1997 and the anti-malarial efforts of the government. The current vivax malaria incidence indicates that exponential growth is not occurring. However, the annual volatility of the pattern of sharp decline since 2000 may also correlate to changes in the environment of the parasite and the mosquito in the endemic areas of Korea.

Although the incidence of malaria is directly affected by the malaria parasites and individuals bitten by infected mosquitoes, climate factors such as temperature, precipitation, humidity, rainfall, and flooding also play critical roles [39]. The correlation between climate change and increased malaria risk in Korea is under investigating. However, there are concerns that changing climate determinants will have an impact on the incidence of malaria. For example, climate change might potentially lead to increased locally-acquired autochthonous transmission by enhancing the growth, survival, and distribution of mosquitoes that can mediate malaria and by changing human activities [39–41]. Thus, efforts to suppress vivax malaria cases should be maintained so that no intrinsic potential for transmission remains.

CASE DISTRIBUTION AND SEASONAL TRENDS

Cases of vivax malaria were limited and sporadic from 1993–1996 but endemic thereafter (Table 1). The incidence of malaria rapidly increased from 0.01/100,000 population in 1993 to 8.52/100,000 population in 1998, peaking at 8.98/100,000 population in 2000 (Table 3). A total of 34,487 indigenous vivax malaria cases were officially reported in Korea from 1993–2017. Although a substantial decrease in the annual number of malaria cases was observed in recent years, vivax malaria still remains endemic in Korea.

Incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of vivax malaria from 1993 through 2017 according to the Province

Malaria in Korea is unstable and seasonal, with 94% of cases (32,429 of 34,487 cases) occurring between 1993–2017 reported between May and October when malaria vectors exist in the field (Table 1). This seasonal distribution pattern of malaria cases has not changed over time and has not been affected by the decline in malaria transmission. Indigenous malaria cases that occurred in the first 4 months of the calendar year, winter and spring, might comprise P. vivax infections contracted in the previous malaria season that had a subsequent prolonged incubation. Such prolonged incubation cases account for approximately 60% of cases annually [38].

Malaria is detected in all age groups, but the most affected group is the 20–29-year-old group (10,317 of 20,544 cases [50.22%] in 2001–2017; Table 4). Malaria incidence in males (17,140 of 20,544 cases [83.43%] in 2001–2017) was markedly higher than that in females (3,404 of 20,544, 16.57%) (Table 4). Although there was a progressive decline in vivax malaria cases in individuals over 17 years of age from 2001–2017, the majority of cases were reported in young men 20–29 years of age (10,317 of 20,544 cases, 50.22%) (Table 4). Males 40–49 years of age comprised the group with the second highest number of cases (3,051 of 20,544, 14.85%) (Table 4). The notably higher case prevalence in 20–29-year-old males suggests an increase in the risk of infection outside their places of residence, as these males are the most mobile members of the population and are most likely to be working in the fields or serving as military personnel in Korea. This is consistent with the fact that human contact with vector mosquitoes and the distance between human residences and mosquito habitats are pivotal conditions determining the incidence of malaria [42].

IMPORTED CASES

The number of imported malaria cases has increased in Korea over the past 20 years (Table 1). Most cases of imported malaria were infections with P. falciparum or P. vivax. Infections with P. falciparum were mainly acquired in Africa, and vivax malaria infections mainly in Southeast Asia, consistent with the typical parasite frequencies of these areas. Imported malaria has a higher incidence in males than in females. Similar demographics have been reported in European countries [43–45]. Males in their 20s are most likely to be infected with imported malaria, likely because they are more likely to travel to areas with a high risk of malaria infection and participate in experiential tourism [43–45].

MOSQUITO VECTOR

A dramatic reduction in the incidence of vivax malaria has been achieved through large-scale national control systems in Korea. Yet, active transmission still persists, particularly in Incheon-si and northern part of the Gyeonggi-do. Control of the mosquito vector is essential for the eradication of malaria. Vector, pathogen, and host controls are the principal strategies of an effective malaria control program. The use of national media to increase the awareness of the need for personal protection against mosquitoes should also aid in transmission reduction.

Malaria is transmitted to humans by the bite of a female anopheline mosquito vector carrying malaria parasites during the acquisition of a blood meal. These vector populations depend on specific climatic and sociodemographic factors. P. vivax is transmitted in Korea by 6 Anopheles species (the Hyrcanus Group): An. sinensis sensu stricto, An. belerae, An. pullus, An. kleini, An. sineroides, and An. lesteri [46,47]. The Hyrcanus group of Anopheles mosquitoes typically dwells near irrigation ditches, ponds, ground pools, and uncultivated fields [48]. Studies of the infection capacity of An. sinensis, the most dominant Hyrcanus species in August, September, and October, and the primary vector of malaria in Korea, have been conducted [48–50]. However, an understanding of the other 5 species remains elusive [51]. The frequency of contact of An. sinensis with humans is very low because this vector is highly zoophilic [52,53]. Other factors reducing the contact are the widespread application of personal protection against mosquito bites [54] and the low to moderate longevity of An. sinensis in Korea [19,49]. Thus, the opportunity for malaria transmission by mosquitoes appears limited. In addition to the 6 major Anopheles species, An. koreicus and An. lindesayi japonicus (from the Barbirostris and Lindesayi group, respectively) have been reported in Korea [55–58]. However, the incidence of malaria due to these 2 vectors has not been studied. It is presumed that these 2 species live mainly in swamps and stream margins, including stream inlets and pools [48,59], with low human-vector contact preventing human blood meals and P. vivax infection. However, there is no evidence that these species cannot develop or propagate malaria parasites. Additionally, no systematic reports have focused on the densities of the malaria vector mosquitoes as active disease vectors from 1993–2017. The only related report was issued by the KCDC, which chronicled the monitoring of malaria vector mosquito density and P. vivax malaria infections since 2009 [60]. From 2013–2014, the density of An. sinensis increased at most collection sites with the same high tendency of annual mean temperature and precipitation [61]. More research on malaria vectors in Korea is needed to provide detailed information about P. vivax transmission capacity. The hypnozoites that cause relapse may be activated weeks or months after the initial infection. Little is known about the biology and determinants of this latency [62].

INCUBATION PERIOD OF P. vivax MALARIA

In Korea, tertian malaria consists of 2 sub-groups. A non-latent group displays symptoms 10–21 days after infection (a short incubation period) [63]. A latent group displays symptoms 6–18 months after infection (a longer incubation period) with unusual biological characteristics and the presence of hypnozoites. In addition, the observed distribution of latent and non-latent infection reflects the adaptation of the parasite to the seasonal population dynamics of the An. sinensis vector, ensuring continued transmission of vivax malaria in this temperate zone despite a long winter period [63]. The occurrence of this long-term latency in vivax malaria in Korea over all four seasons impedes disease management at the national level.

In Korea, vivax malaria transmission is largely limited to the DMZ. Sixty to seventy percent of patients, including those diagnosed in the summer, are classified as long-term latency patients [38]. By monitoring travel routes of people living in non-endemic areas from 2000–2003, the mean duration of long-term latency was identified as 48.2 weeks (337.4 days), which was 12.7 times longer than that of short-term latency (26.6 days) [63]. The factors affecting long-term latency remain unclear, but it is presumed that temperature, infection time, and number of sporozoites play a role. It has also been hypothesized that differences in latency periods among populations may involve parasite genetics and/or the vector’s capacity for sporozoites. It was recently reported by Goo et al. [64] that the genotype of PvMSP-1 is related to the duration of the latent period. The PvMSP-1 recombinant type was predominant in the long latent period samples, while the PvMSP-1 Sal-1 type was most prevalent in the short latent period.

FUTURE STRATEGIES FOR THE ELIMINATION OF VIVAX MALARIA IN KOREA

Malaria has been an endemic disease in Korea for 25 years since its re-emergence in 1993, with a rapidly increasing trend up until 2000. Since then, there has been a mixed pattern of repeated increases and decreases in malaria outbreaks but a steadily declining trend in overall incidence. Academia, central government, local governments, and the military are carrying out various projects that include rapid patient discovery and treatment, and vector control with the basic goal of malaria elimination through treatment, intervention, and pathogen management. Korea is now reaching the pre-phase of malaria elimination, but outbreaks still continue. Additional efforts are needed for the complete elimination of malaria within the next few years and ongoing prevention.

Microscopic examination as a method to diagnose malaria has some limitations, but this method is regarded as the gold standard. Microscopic examination requires skilled specialists to prepare and examine blood smears. Furthermore, sample preparation and inspection are time-consuming. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based diagnostic protocols have been recognized as powerful tools to detect malaria infection and differentiate the infected species with high specificity and sensitivity [65,66]. Nevertheless, PCR methods also have limitations, such as high cost and low applicability without adequate laboratory equipment. The rapid diagnostic test (RDT) has replaced microscopic examination in many malaria endemic countries worldwide because of its relatively reliable diagnostic performance and easy applicability. However, the RDT also has several drawbacks including its low sensitivity against low parasitemia blood samples. To overcome these shortcomings, a new tool that can detect very small amounts of antigen and antibody is needed. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3, similar numbers of vivax malaria cases were reported from 2014–2017, implying that a steady state of malaria transmission in Korea has been maintained in recent years. Therefore, efforts toward more intensive and systematic malaria surveillance, especially in Incheon-si and the northern part of Gyeonggi-do, are necessary to reduce the potential for future increases in malaria cases in endemic areas. The re-emergence of malaria at the DMZ in 1993 is regarded as an unstable malaria transmission that spontaneously appeared and disappeared within a short period of time without a clear reason [31]. To achieve the goal of complete malaria eradication in Korea, it is necessary to consider re-introduction of active case detection, as employed in the 1960s and 1970s.

In general, the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) antibody is produced by sensitization to the antigen presenting cell (APC) when the sporozoite circulates in the human body for 30 to 60 minutes. The CSP antibody has a short half-life that disappears before the next epidemic [67]. In the winter season, a survey for the presence of the CSP antibodies among the residents of high malaria risk areas in Paju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Cheolwon-gun, Gangwon-do, and Gangwha-gun, Incheon-si, might be useful for providing valuable and indirect data with other malarial antibodies for the certification of complete elimination of vivax malaria in Korea. In addition, new malaria management measures should be carried out in accordance with the situation in 2018.

CONCLUSION

The continued and systematic strengthening of control activities for vivax malaria in Korea is premised on the view that the number of vivax malaria cases has reached a steady-state level after its re-emergence in 1993. In spite of the good prospects for success, elimination has proceeded slowly and has been unsuccessful. The geographic boundary of transmission has not shrunk. These realities provide hints that technical aspects, such as resistance to the vector and drugs, are not primarily important and multiple factors are involved in an effective control system. With the current plateau in the number of malaria cases, more efforts must be made to ensure elimination of vivax malaria in Korea. Thus, the government and private sector have to collaborate in diverse areas including education, agriculture, environment, finance, research, medical inspection, communication, and transportation, and must implement all strategies that feasibly suppress the transmission of the infection. Although, in the past time, vivax malaria were considered to be mostly benign and rarely severe and Korea is one of successfully controlled nations for vivax malaria, the precise pathophysiology of P. vivax infection still remain poorly elusive and there is a critical aperture in the current knowledge on vivax malaria in Korea, for examples, drug resistance against chloroquine and primaquine that have been used for the treatment in Korea, genetic alterations in parasite’s genomic contents, changes in host responses and incubation times etc. Coordinated multidisciplinary struggles are pivotal to bridge this knowledge aperture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Research Grant from Inha University.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.