Previous Infection with Plasmodium berghei Confers Resistance to Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Mice

Article information

Abstract

Both Plasmodium spp. and Toxoplasma gondii are important apicomplexan parasites, which infect humans worldwide. Genetic analyses have revealed that 33% of amino acid sequences of inner membrane complex from the malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei is similar to that of Toxoplasma gondii. Inner membrane complex is known to be involved in cell invasion and replication. In this study, we investigated the resistance against T. gondii (ME49) infection induced by previously infected P. berghei (ANKA) in mice. Levels of T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody responses, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations were found higher in the mice infected with P. berghei (ANKA) and challenged with T. gondii (ME49) compared to that in control mice infected with T. gondii alone (ME49). P. berghei (ANKA) + T. gondii (ME49) group showed significantly reduced the number and size of T. gondii (ME49) cysts in the brains of mice, resulting in lower body weight loss compared to ME49 control group. These results indicate that previous exposure to P. berghei (ANKA) induce resistance to subsequent T. gondii (ME49) infection.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria, a disease transmitted by mosquitoes which infects humans, has become prevalent in both the tropics and subtropical regions of the world. Malaria is the most important disease among the 6 diseases selected by the World Health Organization (WHO) due to parasitic infestations that causes about 300 to 500 million malaria infections each year, of which more than 1 million patients die [1]. Malaria is an acute febrile infectious disease caused by parasitism in red blood cells and liver cells. Symptoms associated with this disease include periodic fever, anemia, vomiting and jaundice [2].

Similar to malaria, toxoplasmosis also occurs worldwide, and infection rates do not differ between countries. Toxoplasma gondii is a common infectious organism that infects various types of mammals, including humans and it has been documented that about 1/3 of all humans are exposed to this parasite [3]. Once infected, T. gondii can spread to all organs such as the brain, eyes, heart, and muscles, and can lead to death in immunocompromised individuals. Pregnant individuals are also at risk as birth defects are highly plausible. To date, there is no vaccine against toxoplasmosis [4].

The inner membrane complex is made up of flattened membrane sacs termed alveoli, which are supported on the cytoplasmic face by a highly organized network of intermediate filament-like proteins known as the subpellicular network (SPN) and by interactions with the microtubule cytoskeleton. Also, the inner membrane complex has a number of important roles in the complex life cycles of these parasites [5,6], including providing structural stability, as an important scaffold in daughter cell development and as the location of the actin-myosin motor complex, a key component in parasite motility and host cell invasion [7,8]. Recently, understanding of the structure and components of the inner membrane complex has significantly increased with the recognition of various subdomains within the inner membrane complex and its dynamic composition throughout cell division and maturation. The functions of the inner membrane complex of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium berghei are similar, but differences do exist. In T. gondii, 2 daughter buds arise from the maternal parasite through a process called endodyogeny, whereas multiple daughters are formed through merogony in Plasmodium spp.

Analysis of the same gene, inner membrane complex, in P. berghei and T. gondii showed that 33% were similar [9,10]. T. gondii and Plasmodium parasites have been documented to share similar traits, especially with respect to biochemical and molecular pathways involved in pathology, immunomodulation, and metabolism [11]. This may indicate that parasites during co-infection can result in a competitive establishment that can promote or inhibit parasitological pathogenesis and fetal and birth outcomes. Yet, the disease outcome and immunological response induction as a consequence of interaction between Plasmodium and T. gondii remain largely elusive [11]. In this study, we determined the resistance to T. gondii (ME49) in mice induced by malaria P. berghei (ANKA) infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and animal ethics

Female Balb/c 8 mice (7 weeks old) were purchased from KOATECH (Pyeongtaek, Korea). P. berghei (ANKA) and T. gondii (ME49) were maintained in mice by serial intraperitoneal passage. Groups of mice (n=8) were infected with 1%/100 μl of P. berghei (ANKA) by intraperitoneal (IP) injection. One hundred T. gondii (ME49) cyst were used to infect the mice via oral route. To determine the resistance to T. gondii infection, mice were primarily infected with Plasmodium berghei, and treated to remove malaria in the blood at day 7. The treated mice were subsequently infected with T. gondii (ME49). All of the experimental procedures involving animals have been approved and conducted under the guidelines set out by Kyung Hee University IACUC (KHUASP [SE]-17-078).

Parasite antigens preparation

T. gondii RH tachyzoites were harvested from the peritoneal cavity of mice 4 or 5 days after infection by injecting 3 ml of 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) as described [13]. Peritoneal exudate was centrifuged at 100 g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The parasites in the supernatant were precipitated by centrifugation at 600 g for 10 min, which were washed in PBS and sonicated. P. berghei (ANKA) antigen was prepared as described previously [14]. The P. berghei-infected red blood cells (RBCs) were collected from whole blood of mice with parasitemia exceeding 20% by low speed centrifugation (1,500 rpm, 10 min) at 4°C. The RBCs pellets were lysed with equal volume of 0.15% saponin in PBS for 10 min at 37°C and the released parasites were pelleted and washed 3 times with PBS (13,000 rpm for 1 min at 4°C) [15]. Parasites were sonicated twice for 30 sec at 40 Hz on ice and used as coating antigens for ELISA.

Assay on antibody response

Blood samples were collected at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after challenge infection with T. gondii (ME49). T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a, IgG2b response was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 96-well plates (SPL, Pocheon, Korea) were coated with 4 μg/ml of T. gondii (RH) antigen at 4°C overnight [17]. The plates were washed and then blocked with 0.2% gelatin in PBST for 2 hr at 37°C. After washing, diluted sera (1:100) samples were added and incubated for 2 hr at 37°C. Antibody responses were detected using the HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG [18]. The substrate O-phenylenediamine in citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0), containing 0.03% H2O2, was used to develop color and stopped with 2N H2SO4. The optical density at 490 nm was measured with an ELISA reader.

Reagents

SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (10,000×concentrate in DMSO, Cat. No. S9430) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California, USA). Other reagents saponin (Cat. NO. 47036) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and CD3e-PE-Cy5, CD4-FITC, CD8a-PE markers were purchased form BD Biosciences (San Jose, California, USA). Goat anti-mose IgG-HRP purchased from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, Alabama, USA).

Assay on parasitemia

For staining of infected RBC, 2 μl of blood obtained from the retro-orbital plexus puncture of infected mice was collected into a 1.5-ml tube containing 100 μl of a premixed stock of PBS with 500 U/ml of heparin. RBCs from P. berghei (ANKA) infected mice were stained using 1 μl SYBR Green I. The samples were incubated in a dark 37°C incubator for 30 min and then flow cytometry was performed [16].

T. gondii ME49 cyst count and size in the brain

One month after infection with T. gondii, the brains of mice were collected and finely ground in 200 μl PBS using a syringe. Approximately 5 μl of homogenized brain tissue lysate was placed on a glass slide and observed under the microscope to count and measure the sizes of cysts [13]. All samples were counted thrice to reduce counting errors.

CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells populations from splenocytes of mice at 1-month post-challenge infection were analyzed by flow cytometry. Splenocytes (1×106 cell/ml) in staining buffer (2% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide in 0.1 M PBS) were incubated for 15 min at 4°C with Fc Block (clone 2.4G2; BD Biosciences) [19]. For surface staining, cells were incubated with surface antibodies (CD3e-PE-Cy5, CD4-FITC, CD8a-PE, BD Biosciences) at 4°C for 30 min. Splenocytes were washed with staining buffer and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min before acquisition using BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using C6 Analysis software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All parameters were recorded for individuals within all groups. Statistical comparisons of data were carried out by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test or student t-test using PC-SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A P-value<0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

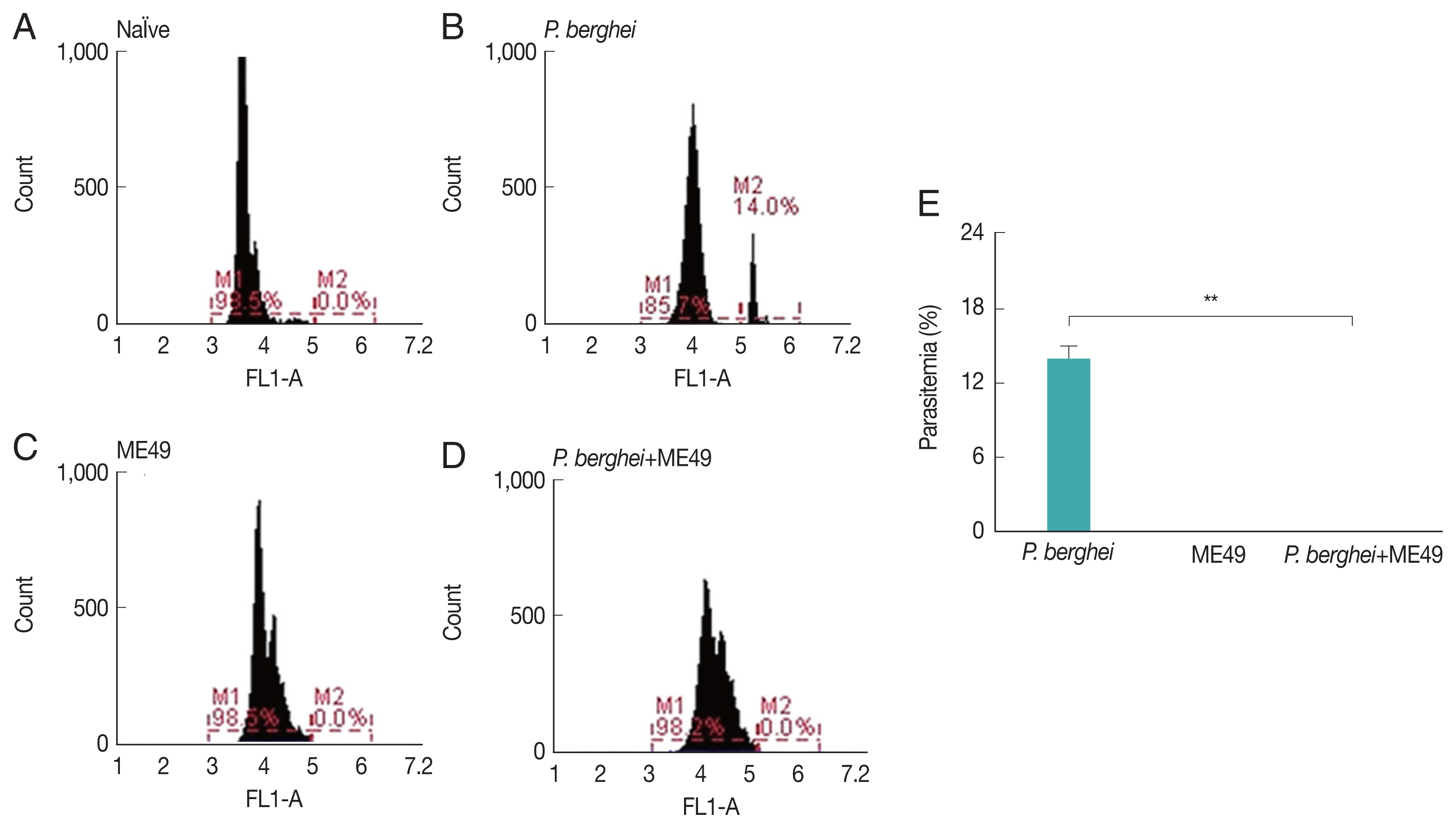

Parasitemia induced by P. berghei

Parasitemia levels in blood were measured from all groups, including naïve mice and P. berghei infected mice (Fig. 1E). Mice infected with P. berghei showed 14% increased parasite counts (Fig. 1A, B). P. berghei parasites were not detected from mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii (ME49) alone (Fig. 1C). Absence of parasitemia was also detected from mice challenge-infected with T. gondii, which had previously received anti-malarial treatment to remove malaria in the blood post-P. berghei infection (Fig. 1D).

Parasitemia levels in mice infected with P. berghei. Blood collected from infected mice were used to assess the level of parasitemia by flow cytometry. (A) Naïve mice. (B) Naïve mice infected with P. berghei. (C) Mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii. (D) Mice infected with P. berghei first, then subsequently infected with Toxoplasma gondii. (E) Average parasitemia per group is shown in the bar graph (**P<0.01).

T. gondii-specific antibody responses

The T. gondii-specific antibody responses profiles in sera were determined as scheduled. P. berghei+ME49 mice induced significantly higher T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibody responses at weeks 1, 2, and 4 than mice infected with T. gondii alone (Fig. 2). T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibody responses were found to be higher at week 4 compared to those at weeks 1 or 2 in P. berghei+ME49 mice. These results indicate that T. gondii–specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibodies were successfully boosted due to previous exposure to malaria.

Antibody response profiles against T. gondii antigen. Mice were primarily infected with P. berghei, and at week 4, mice were subsequently infected with T. gondii ME49. T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody responses (A, B) in the sera were determined at weeks 1, 2, and 4 post-infection with T. gondii (mean±SD, *P<0.05).

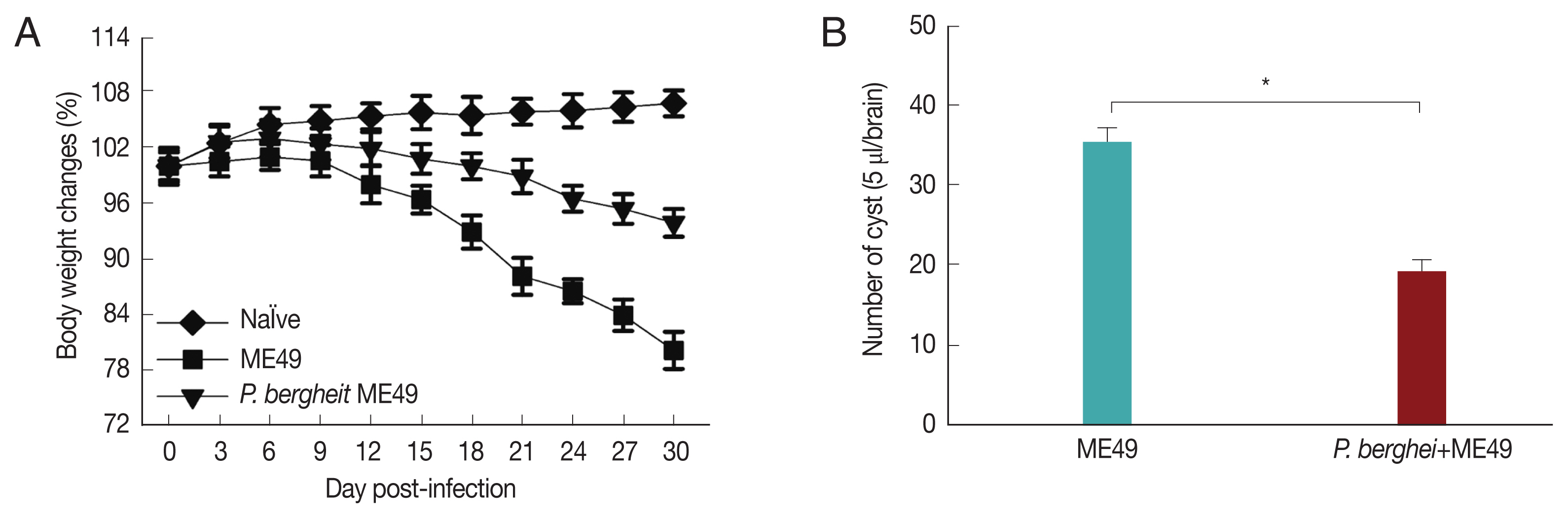

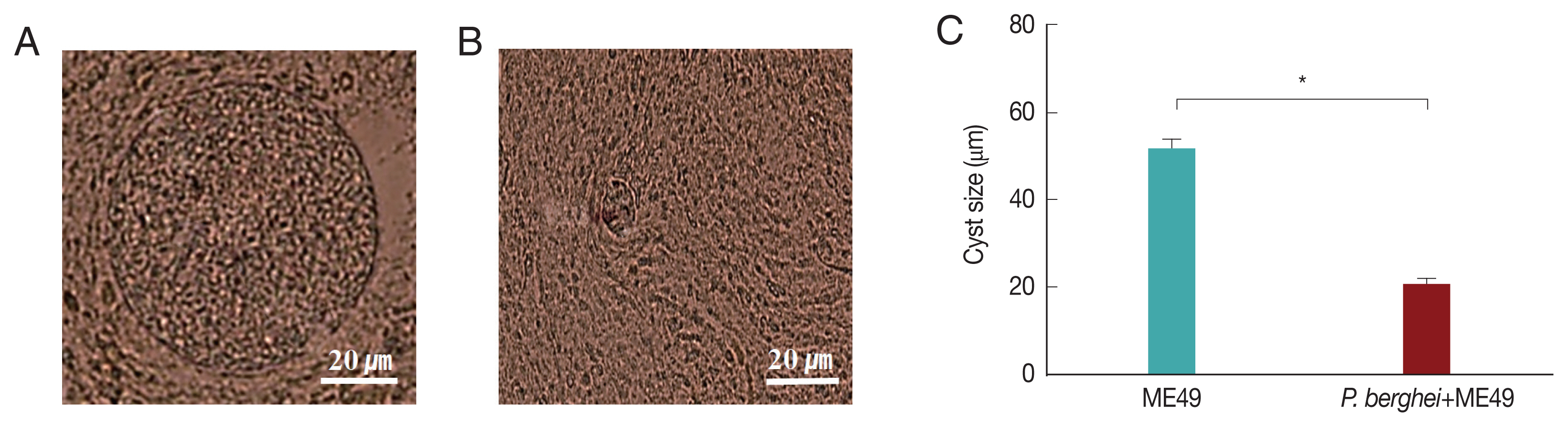

Previous infection with P. berghei shows resistance to T. gondii infection

Fig. 3A showed that P. berghei+ME49 mice had a 15% less reduction in body weight compared to mice infected with T. gondii (ME49) alone. In addition, in Fig. 3B, the number of T. gondii (ME49) cysts in 4 mice infected with P. berghei also decreased by 55%. As shown in Fig. 4C, 4 mice infected with P. berghei (ANKA) showed a 38% reduction in cyst size compared to mice infected with ME49 alone. The average cyst size was about 52 μm in the ME49-infected mice (Fig. 4A), whereas the cyst size was about 20 μm in the ME49-infected mouse which had previous exposure to P. berghei (Fig. 4B). This suggests that previous infection with P. berghei (ANKA) confers resistance to infection with T. gondii (ME49).

Body weight changes and cyst counts in the brain. Mice were primarily infected with P. berghei, and at week 4, mice were subsequently infected with T. gondii. Mice body weight changes were recorded daily upon T. gondii infection and cyst counts in the 5 μl/brain were determined at 1 month after T. gondii (ME49) infection. (A) Body weight changes, and (B) cyst counts (*P<0.05).

Cysts size of Toxoplasma gondii (ME49) in the brain. Mice were sacrificed at 1 month after infection with T. gondii, and cysts were observed in the brain under microscopy. (A) T. gondii (ME49) infection control. (B) Mice infected with P. berghei were subsequently infected with T. gondii malaria. (C) Ten cysts from 1 mouse brain were observed (n=4) (*P<0.05).

Previous infection with P. berghei shows CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses upon challenge infection with T. gondii

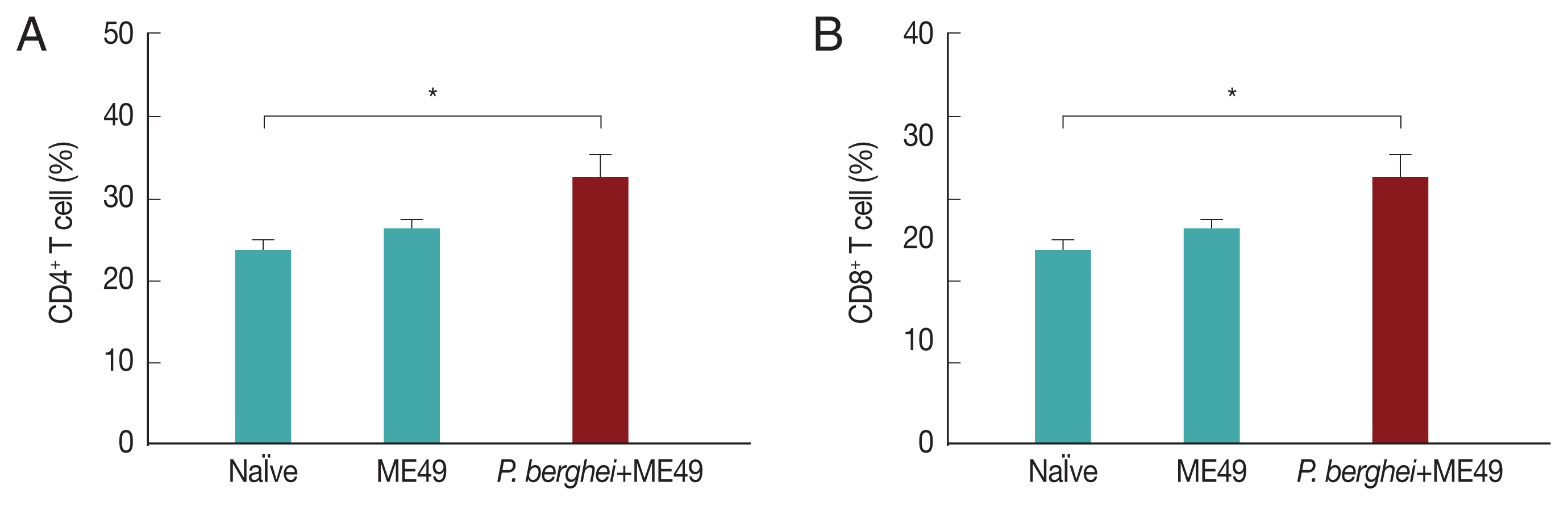

CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell responses are important indicators for assessing immunity induced by infection. CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell responses were determined after sacrifice. As seen in Fig. 5, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in mice infected with T. gondii (ME49) were 26.3% and 21.5% respectively, whereas these populations levels were significantly increased to 32.4% and 25.1% in mice previously infected with P. berghei (ANKA) (Fig. 5). These results indicate that T. gondii (ME49) infected with P. berghei (ANKA) induces more T cell responses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the resistance against Toxoplasma gondii (ME49) in mice previously infected with P. berghei and T. gondii [9,20]. Our results indicate that T. gondii-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a antibody responses, along with CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses contributed to resistance against infection with T. gondii. As far as we know, this is the first report documenting resistance against T. gondii reinfection in P. berghei after treatment. P. berghei (ANKA) used for malaria infection was found to be very important for inhibiting T. gondii (ME49) [21]. In our study, T. gondii (ME49) infection induced greater T. gondii-specific IgG antibody response in mice which had received treatment post-P. berghei infection than control. Specific IgG antibody response detected against P. berghei was also greater than those detected from T. gondii control mice. Compared to the first week after infection with T. gondii (ME49), T. gondii-specific IgG responses doubled by week 4. Antigen-specific IgG1 response was only detected against T. gondii but not P. berghei. In malaria, IgG2a antibodies are primarily involved in controlling parasite infestation. When red blood cells become infected in the early stages of rodent malaria, macrophages are induced. It is possible that activated macrophages stimulate production of IgG2a antibodies, which preferentially attack merozoite-infected RBCs. IgG2a antibody provides important protection from malaria infection, whereas IgG1 antibody does not play an important role in protection [22]. Toxoplasma gondii infection induces a potent, protective Th1 immune response characterized by production of IFN-γ, IL-12 cytokines and IgG2a antibodies. The Th1 immune response induced during T. gondii infection is produced by IL-12 secreted from APC. IL-12 and IFN-γ may also have an impact on the Th2 immune response. T. gondii infection limits the parasite-specific Th2 immune response and induces a Th1 immune response [23]. In addition, marked reduction of brain cyst count was observed and these results can be attributed to enhanced humoral immunity induced upon co-infection [24]. Our results have demonstrated that lesser degree of body weight reduction was observed in mice infected with both P. berghei (ANKA) and T. gondii, in comparison to those infected with T. gondii (ME49) alone. Compared to T. gondii (ME49) control groups, CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell levels were elevated in co-infected mice by 6.1% and 3.6%, respectively [25]. Malaria infection involves accumulation of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IFN-γ and IL-6 along recruitment of various innate immune cells, including but not limited to inflammatory mononuclear cells, macrophages, DCs, and NK cells. IL-12 mediated induction of highly activated parasite-specific CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ (Th1) is also a key to protection against Plasmodium infection [26]. T. gondii infection induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-12, IL-6 and TNF-α. IL-12 differentiates CD4+ T cells into Th1 strains and stimulates IFN-γ release by NK cells in combination with other inflammatory cytokines such as IL-18 and IL-1, which further exacerbates inflammation [27]. The appropriately activated phagocytes respond by secreting IL-12, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 which leads to phagocytosis of parasite-infected host cells. It also activates immune cells such as NK cells and T cells. In second lymphoid tissues, inflammatory cytokine expression continues and parasite antigens are presented on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, leading to T cell activation and proliferation. In particular, IL-12 induces CD4+ T cells to differentiate into potent Th1 cells that secrete large amounts of IFN-γ when activated. Th1 cells and inflammatory cytokines further activate CD8+ T cells [10]. Combining these results, resistance against T. gondii (ME49) due to the activity of Th1 was found through co-infection of P. berghei and T. gondii, which involves contribution from both cellular and humoral immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2018R1A2B6003535, 2018 R1A6A1A03025124).

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.