Abstract

Clonorchis sinensis is a food-borne trematode that infects more than 15 million people. The liver fluke causes clonorchiasis and chronical cholangitis, and promotes cholangiocarcinoma. The underlying molecular pathogenesis occurring in the bile duct by the infection is little known. In this study, transcriptome profile in the bile ducts infected with C. sinensis were analyzed using microarray methods. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were 1,563 and 1,457 at 2 and 4 weeks after infection. Majority of the DEGs were temporally dysregulated at 2 weeks, but 519 DEGs showed monotonically changing expression patterns that formed seven distinct expression profiles. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis of the DEG products revealed 5 sub-networks and 10 key hub proteins while weighted co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)-derived gene-gene interaction exhibited 16 co-expression modules and 13 key hub genes. The DEGs were significantly enriched in 16 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways, which were related to original systems, cellular process, environmental information processing, and human diseases. This study uncovered a global picture of gene expression profiles in the bile ducts infected with C. sinensis, and provided a set of potent predictive biomarkers for early diagnosis of clonorchiasis.

-

Key words: Clonorchis sinensis, bile duct, transcriptome, differentially expressed gene, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a rare but aggressive malignancy, with a 5-year survival rate lower than 10% [

1]. It arises from the bile duct epithelium and can be classified as either intrahepatic CCA or extrahepatic CCA. Several identifiable risk factors for CCA have been identified; among these,

Clonorchis sinensis has been regarded as a group 2 biological carcinogen which can induce human CCA by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [

2]. Both experimental and epidemiological studies convincingly implicate

C. sinensis infection is associated with the etiology of CCA [

3]. Persistent infection and chronic inflammation caused by the liver fluke have recognized as the major risk factor for CCA [

4].

Although the effects of the liver fluke infection on host physiology and host responses have been reported previously [

5], only limited information is currently available on the underlying molecular mechanisms for bile duct changes including CCA induced by

C. sinensis infection. Previous reports on the time-dependent host responses to

C. sinensis itself, and its excretory and secretory products (ESPs) are still scarce and variable responses among the experimental animals [

6,

7]. In these points, investigation on the underlying molecular pathological events in the bile ducts infected with

C. sinensis is important to understand pathology of clonorchiasis as well as to unveil reliable diagnostic markers and drug targets to control the infections and to prevent serious complications by the liver fluke, especially in the high endemic areas [

8,

9].

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks or co-expression networks are very informative to investigate the relationships between disease and genes/proteins, and hence are helpful to identify molecular mechanisms occurring in the certain disease [

10]. Most genes/proteins generally play together for biological tasks. It has been presumed that diverse host-parasite interactions (HPIs) are communicated with receptor-mediated events.

In the present study, overall patterns of significant functional genes and gene sets expressed in the bile ducts of experimental rats infected with C. sinensis were analyzed to understand molecular pathophysiological events in bile ducts. Understanding differential expressions of diverse gene sets in the C. sinensis-infected bile ducts might shed light on the underlying mechanism of carcinogenesis in bile ducts induced by the liver fluke infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites, experimental animals and infections

Clonorchis sinensis metacercariae were collected from naturally infected intermediate host,

Pseudorasbora parva, as described previously [

11,

12]. Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (female, 160–180 g; 6 weeks) were infected with the parasite by oral feeding 100 metacercariae.

C. sinensis infection was validated in all challenged SD rats by observing

C. sinensis worms in bile ducts when sacrificed. Bile duct tissues of SD rats were surgically removed at 2 weeks (2W; n=2) and 4 weeks (4W; n=3) after infection and normal control (NC; n=3) groups under microscopy. Subsequently, the bile duct tissue samples were gently washed five times with sterile cold physiological saline to remove any other tissues and parasites, and were used immediately for RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and quality assessment

Total RNA was isolated from each bile duct tissue sample using the TRI Reagent (MRC, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) according to the protocols of manufacturer and then was dissolved in RNase-free-water. RNA samples were quantified, divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C until use. The quality of RNA was assessed by analyzing RNA purity and integrity with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA).

Labeling and hybridization of microarray

Microarray hybridization was performed as described below. Cyanine-3 labeled complementary RNA (cRNA) was prepared from 1 μg RNA using the One-Color Low RNA Input Linear Amplification PLUS Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions followed by RNAeasy column purification (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). Dye incorporation and cRNA yield were checked with the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The labeled cRNA sample was hybridized on a Whole Rat Genome Microarray 4×44K v3 (Probe Name version, Design ID #028282, GPL14746 platform, Agilent Technologies) using a Gene Expression Hybridization Kit (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Data preprocessing and normalization

After washing the hybridized slides with GE washing buffer, the dried slides were scanned with an Agilent Microarray Scanner (G2505C). Feature extraction software v10.5.1.1 employing default for all parameters was used to convert the scanned images into signal intensities. Spots judged as sub-standards by visual examination of each slide were flagged and excluded for further analysis. The raw data were processed based on the Agilent normalization method using the Babelomics v5 [

13], and normalized to 27,078 probe IDs excluding missing data and subsequently the values were transformed to log base 2. Gene expression data were deposited to NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [

14] and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE136575. For further analysis, gene expression data were adjusted through quantile normalization [

15] and then standardized using EXPression ANalyzer and DisplayER (EXPANDER) v8.0 [

16].

Multi Experiment Viewer (MeV) v4.8 [

17] was used to test the effect of a factor (infection duration) on gene expression. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed on 27,078 normalized probes using

P-values based on permutation (1,000 permutations per probe) with an overall threshold set to 0.05. The

Post-

hoc Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison tests were applied to identify significant differences among the sample groups using Tukey R-package [

18]. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using Linear Models for Microarray Data (LIMMA) R-package [

19] with log

2 Fold Change (log

2FC)≥1 and adjusted

P-value cut-off of 0.05 as implemented in the integrated Differential Expression and Pathway analysis (iDEP) v90 [

20]. Agilent probe IDs were converted into Ensembl gene IDs and gene symbols using the biological DataBase network (bioDBnet) [

21] and HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) Mart (

https://biomart.genenames.org). Probe sets without any annotation or having duplicated gene symbols were filtered out. All significant DEGs were analyzed for their intersections among the different sample groups using the web tool (

https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/).

To identify genes clustering in

C. sinensis-infected and uninfected normal samples, hierarchical clustering (HCL) and principal components analysis (PCA) were performed between genes (n=2,419) and between samples (n=6), respectively. It was applied to probe sets having statistical significance using the iDEP v90 [

20] with average linkage clustering using Pearson’s correlation as similarity metric. HCL was visualized as a dendrogram based on gene and sample distances simultaneously.

Time course data were analyzed using Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM) [

22]. STEM clustering method was applied with rat genome database (

https://rgd.mcw.edu), maximum number (50) of model profiles and maximum unit change (3) between two time points. Probes were filtered out with minimum absolute expression change (1) based on maximum-minimum parameter. The 50 permutations per gene was applied and the

P-value was corrected using the Bonferroni correction where the significance level is divided by the number of model profiles. The

P-values less than 0.001 were considered to be statistically significant. Similar model profiles were significantly clustered each other with minimum correlation of 0.8.

PPI networks for top 400 DEGs were constructed using the Search Tool in the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database v11.0 [

23]. PPIs included direct and indirect interactions derived from three connection sources, such as “Experiments”, “Databases”, and “Co-expression”. The minimum interaction parameter was set as a medium confidence threshold of 0.4. The PPI networks were imported into Cytoscape v3.7.2 [

24] using the StringApp v1.5.1 plug-in [

25]. Significant sub-networks were explored using the ClusterONE v1.0 plug-in [

26] with a minimum size of 5 and remaining parameter as the default. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs in each cluster was carried out using the ClueGo v2.5.7 plug-in [

27]. Significantly enriched pathways (

P<0.05) were visualized using CluePedia v1.5.7 plug-in [

28]. Hub proteins were chosen using the cytoHubba v0.1 plug-in [

29] with Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) method. All networks were visualized in the Edge-weighted Spring Embedded Layout.

Co-expression networks and modules were identified using Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) R-package [

30]. To minimize noise in the correlation matrix, a soft threshold of 18 was chosen for the limited number of samples according to the recommendation [

31] and set the minimum module size to 200 genes. Genes in each module within each network were analyzed for enriched GO gene sets using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [

32] with a minimum module size filter of 20 and default Edge threshold of 0.4. The module networks were imported into the Cytoscape [

24] and hub genes were visualized with the cytoHubba plug-in as described above.

KEGG enrichment analysis of all DEGs having statistical significance was performed and the matched genes were mapped on the KEGG pathways using PaintOmics v3 [

33]. KEGG enrichment results were plotted using FuncTree [

34]. Image was labeled and formatted using Inkscape graphics software v1.0beta2 (

http://www.inkscape.org).

RESULTS

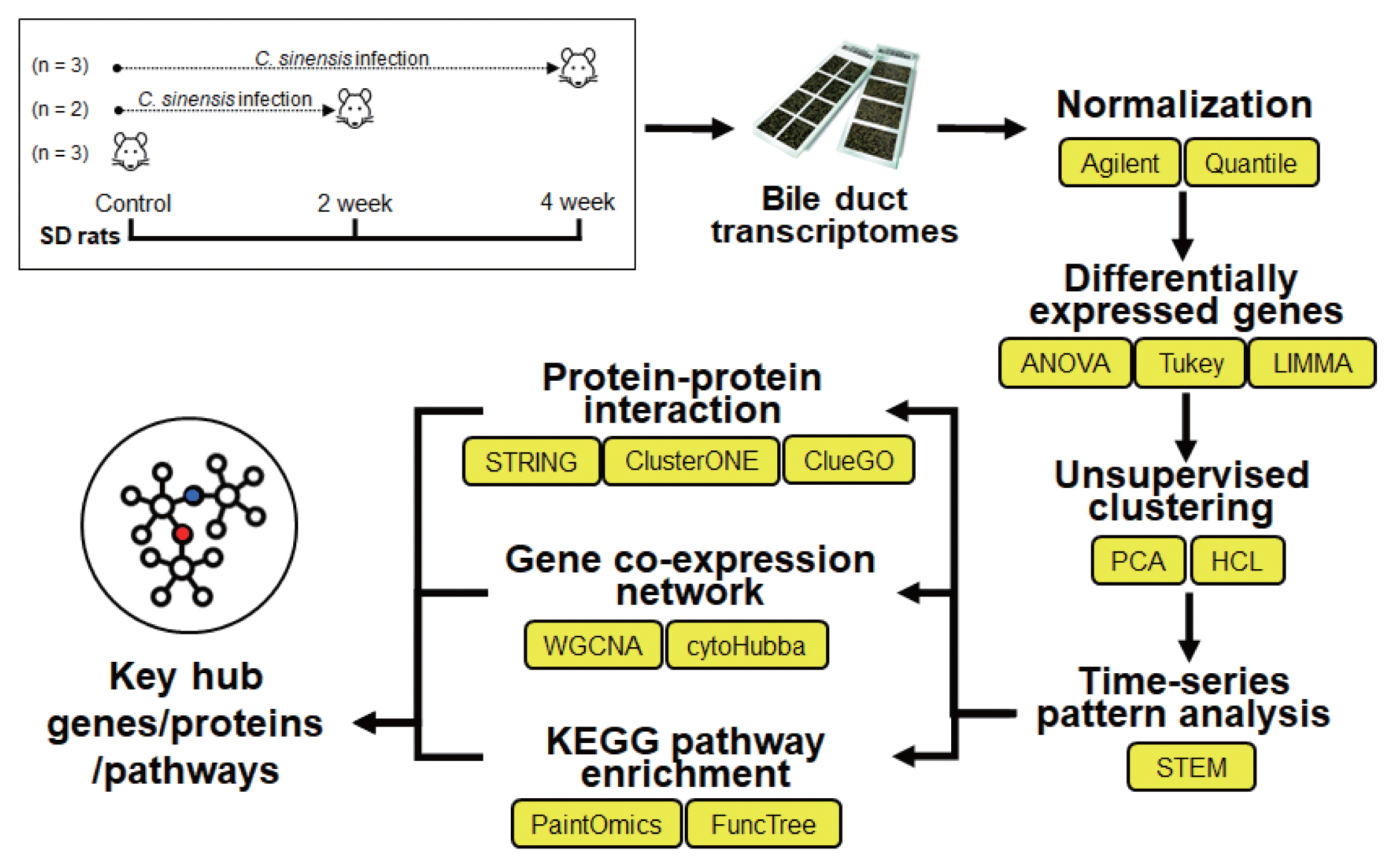

Microarray preprocessing and normalization

An integrative bioinformatic analysis of microarray data was performed to investigate transcriptional regulation of co-expression genes and pathway-related genes in the bile ducts of SD rats involving

C. sinensis infection (

Fig. 1). At first, all probe datasets (n=8) were within-array normalized by the Agilent normalization; NC (n=3), 2W (n=2) and 4W (n=3) of

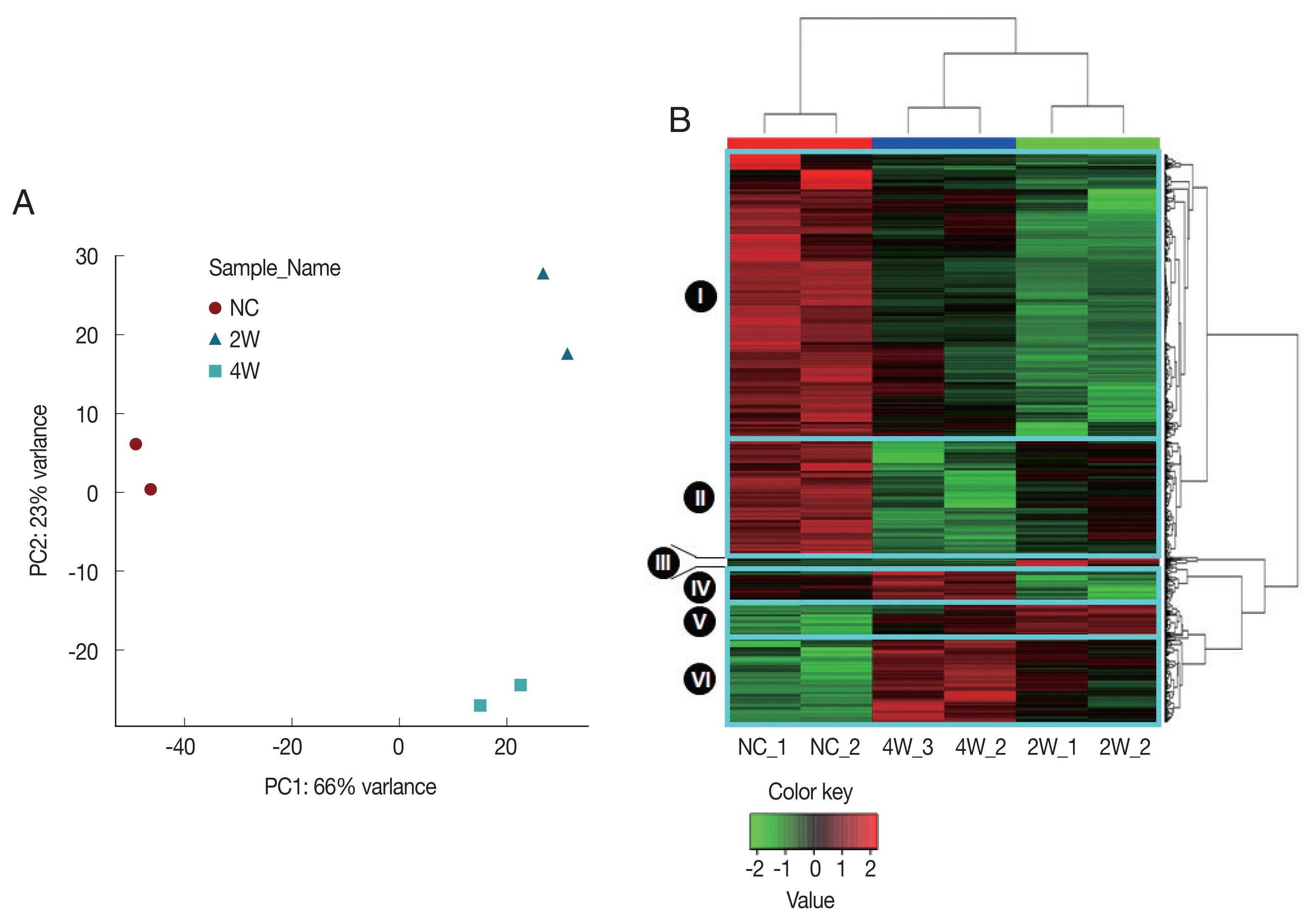

C. sinensis. Among them, NC_3 and 4W_1 samples were excluded because they didn’t closely match to the corresponding experimental group with preliminary PCA and HCL (data now shown). Remaining data were log2-transformed, performed between-array normalization by the quantile normalization method, and finally standardized (normalization of each expression pattern to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1).

After preprocessing, group-wise comparisons were carried out using one-way ANOVA test at each time point after

C. sinensis infection. The group comparisons revealed significant gene expression changes between each group; statistically significant 2,895 genes (

P<0.05) were survived across 27,078 normalized time course probes. The observed differences between any two groups were confirmed to be significant using

post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests [

18] (

Table 1). A total of 2,419 DEGs were chosen to be significantly altered in

C. sinensis-infected groups compared to NC, |log

2FC|≥1 and

P<0.05 in at least one infection condition, as identified by LIMMA [

19]. All probes of all samples including DEGs in any condition were further analyzed with unsupervised PCA and HCL to validate array quality and sample level variances. The PCA plot visually indicated that 2W and 4W were separated from NC along Principal Component 1 (PC1), accounting for 66% of the variations in

C. sinensis-infected groups (

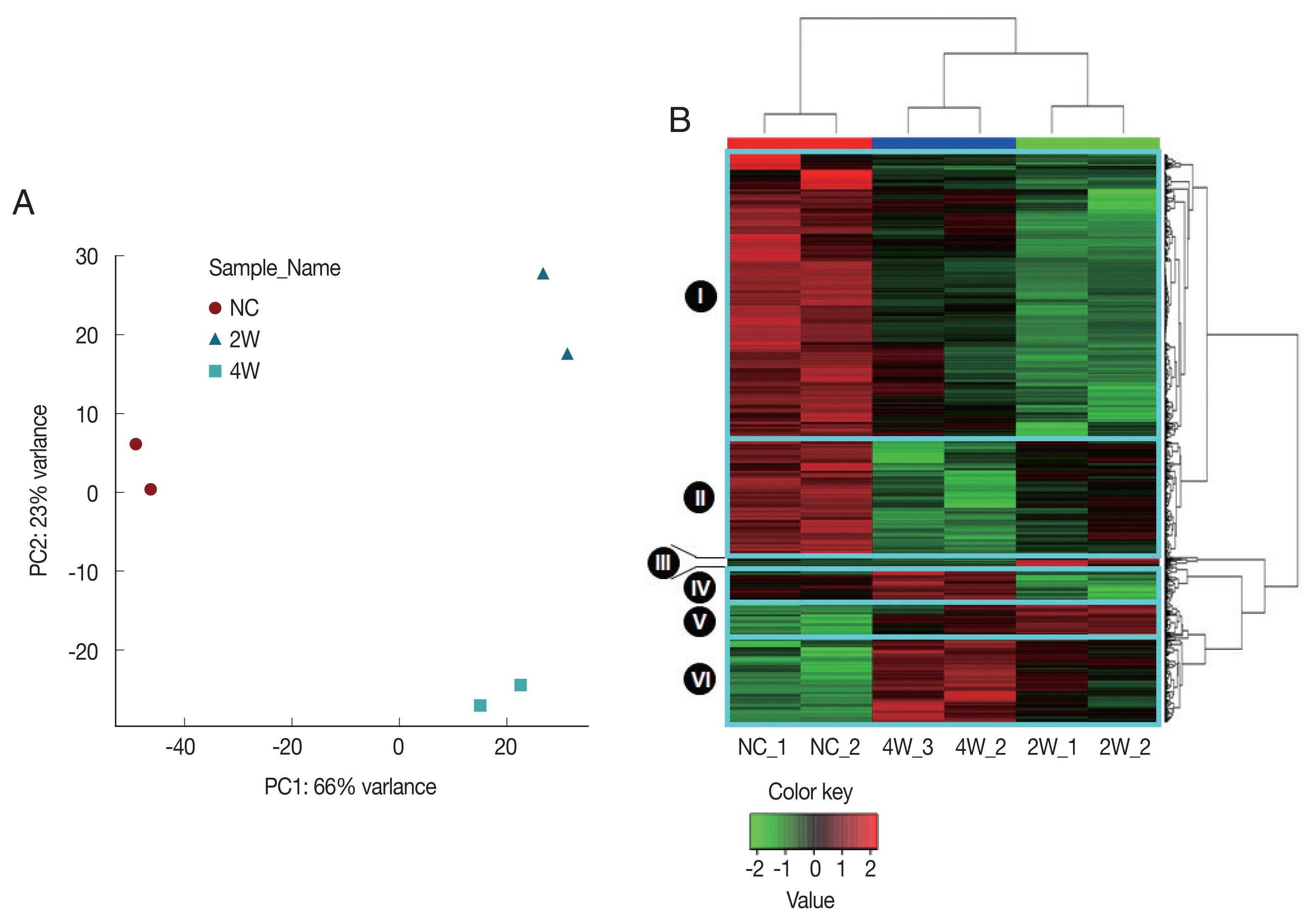

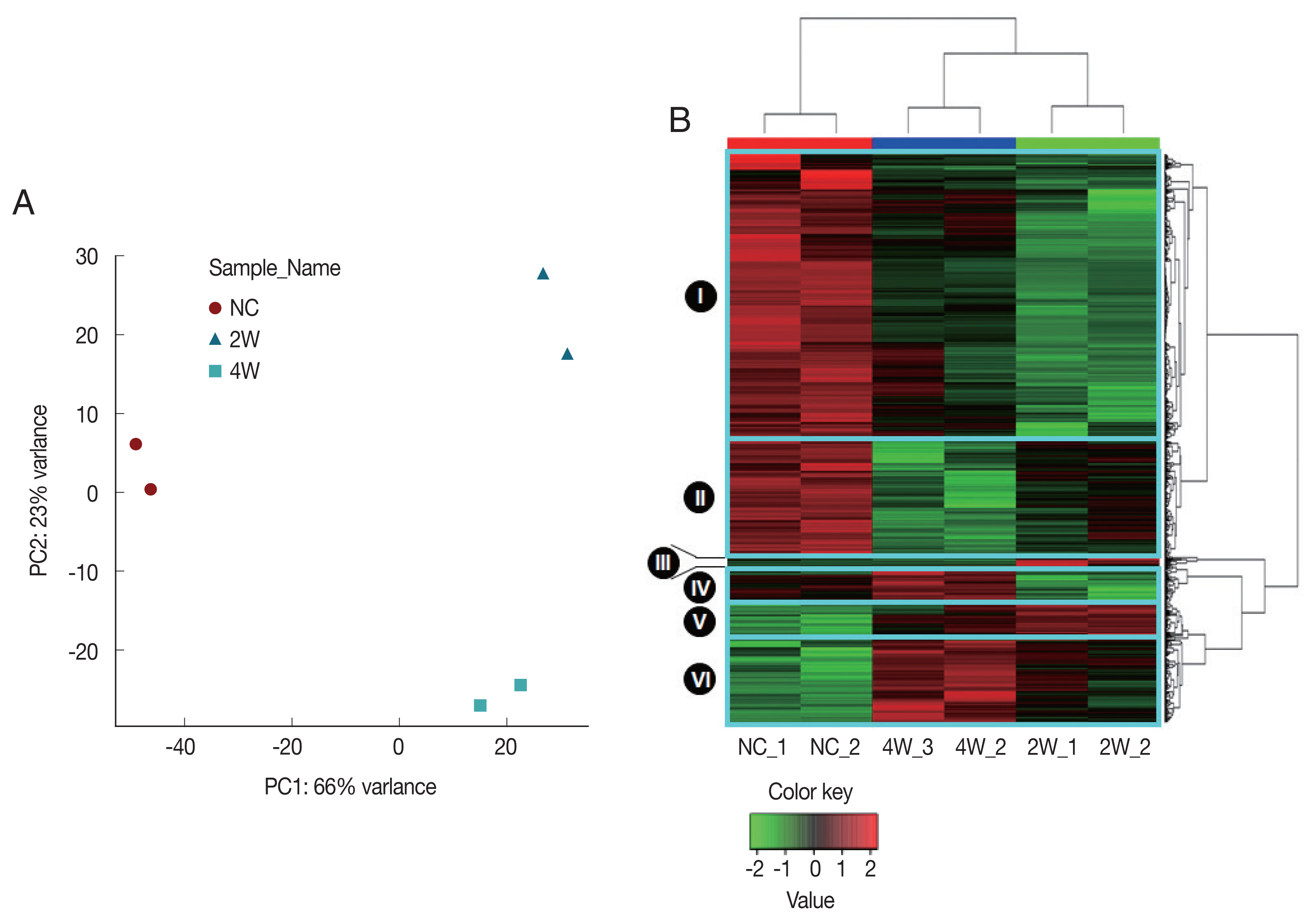

Fig. 2A). Three distinctive clusters corresponding to each biological group were identified based on the transcriptional profiles. The relative position of the samples demonstrates a higher correlation in intragroup than intergroup conditions, revealing an early qualitative and quantitative alterations of gene transcripts. These demonstrate that transcriptional differences compared to NC were greater at 2W than at 4W.

Similar gene expression patterns were also observed in the HCL, in which gene expression profiles split 2W and 4W versus NC (

Fig. 2B). Three distinct major regulation features were observed; (1) a major number of genes in the clusters I and II were highly expressed in NC, but down-regulated at 2W and 4W, (2) expressions of some genes in the clusters II and VI were monotonically increased or decreased during the infection (monotonically changing DEGs). (3) some genes in the clusters I, III, IV and V were temporally dysregulated in

C. sinensis infection (

Fig. 2B).

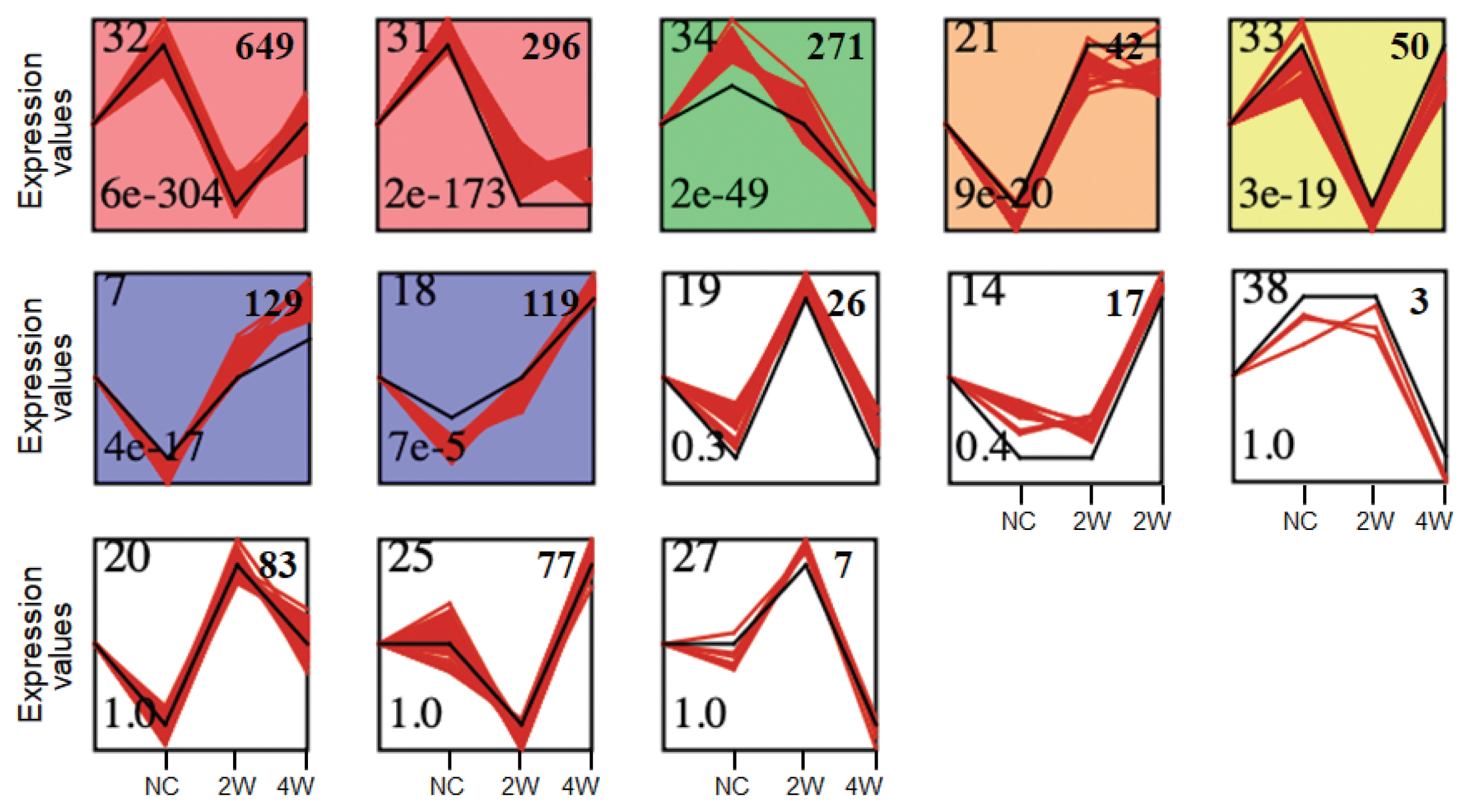

Given the 1,771 DEGs (only genes having Ensembl gene IDs [

35]), genes with highly similar response profiles were sought using the STEM [

22]. The DEGs were clearly clustered into seven profiles based on expression patterns over time in

C. sinensis infection (

Fig. 3). A large percentage of 1,037 DEGs were significantly overrepresented in the Profiles 32, 31, 21, and 33 (

P<0.05), in which gene expression levels were temporally dysregulated. Among these, 699 genes of the Profiles 32 and 33 were suppressed at 2W but induced at 4W. Meanwhile, 271 genes showed monotonically decreasing expression (MDE) patterns in Profile 34 (

P<0.05) over the time course of infection and 248 genes revealed monotonically increasing expression (MIE) patterns in Profiles 7 and 18 (

P<0.05). These genes showing monotonically changing expression patterns are considered to be core responses induced by

C. sinensis infection. These findings indicate more robust transcriptional changes occur at early stage of infection (2W), such as Profiles 32, 31, and 21.

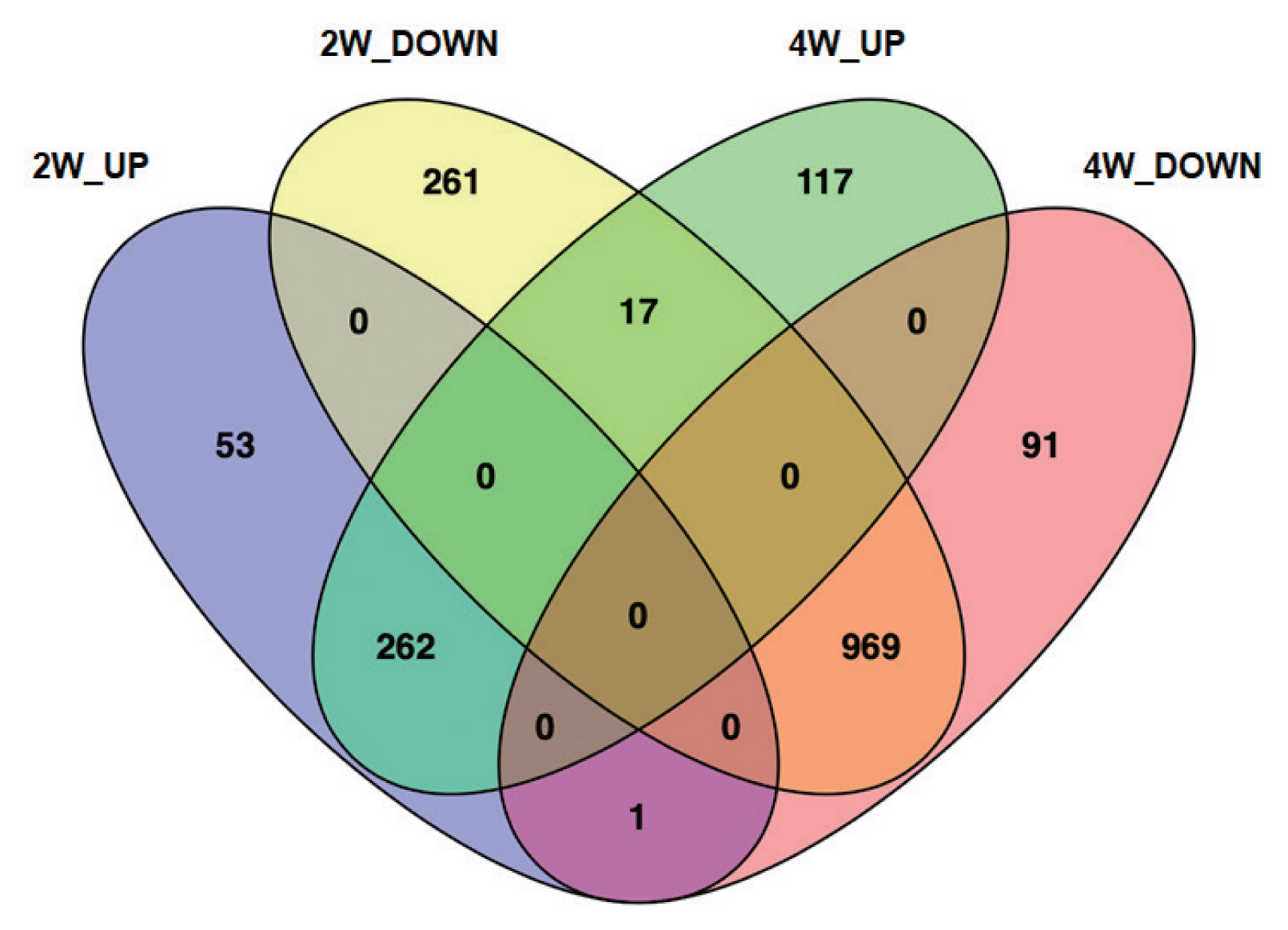

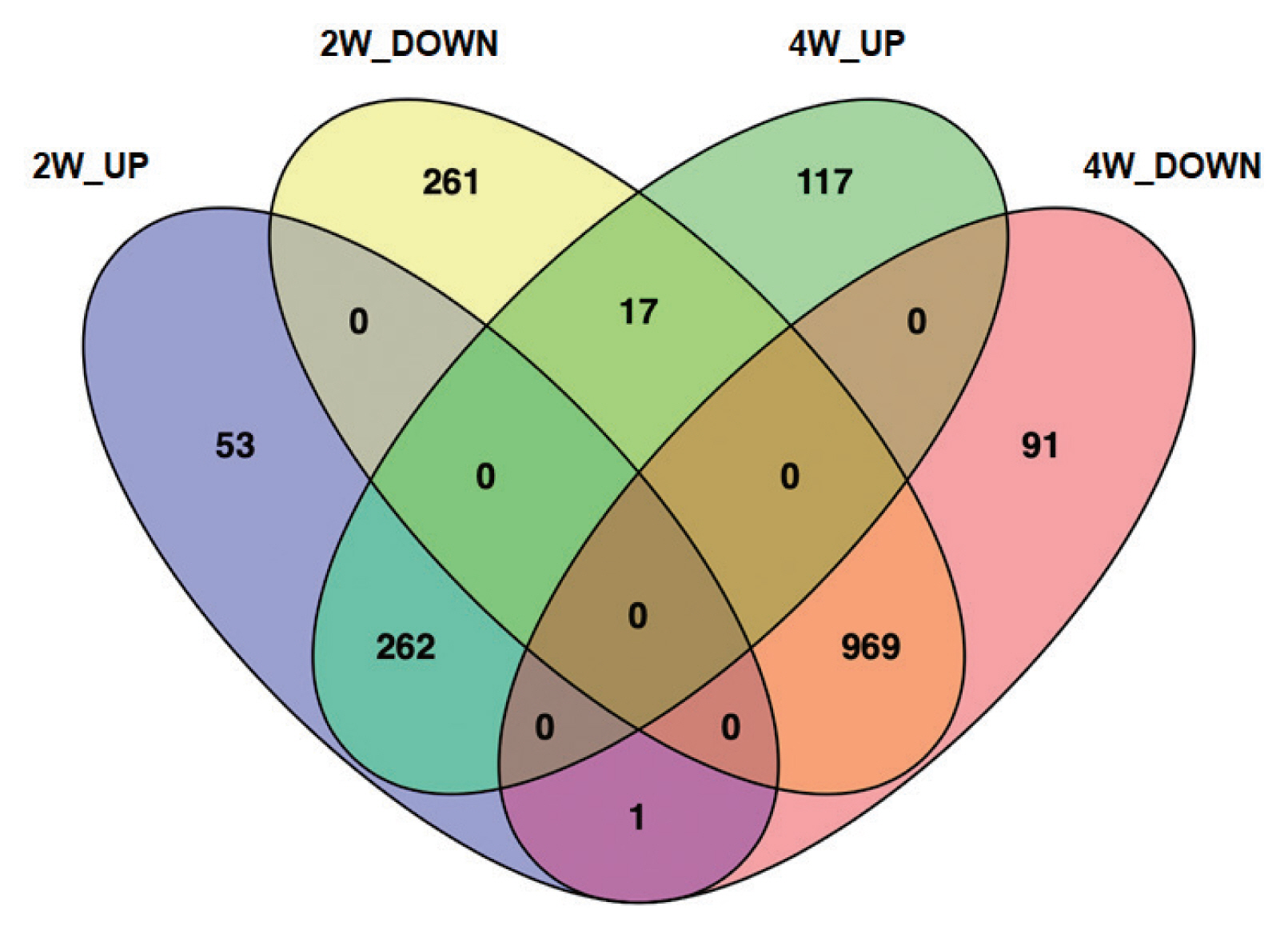

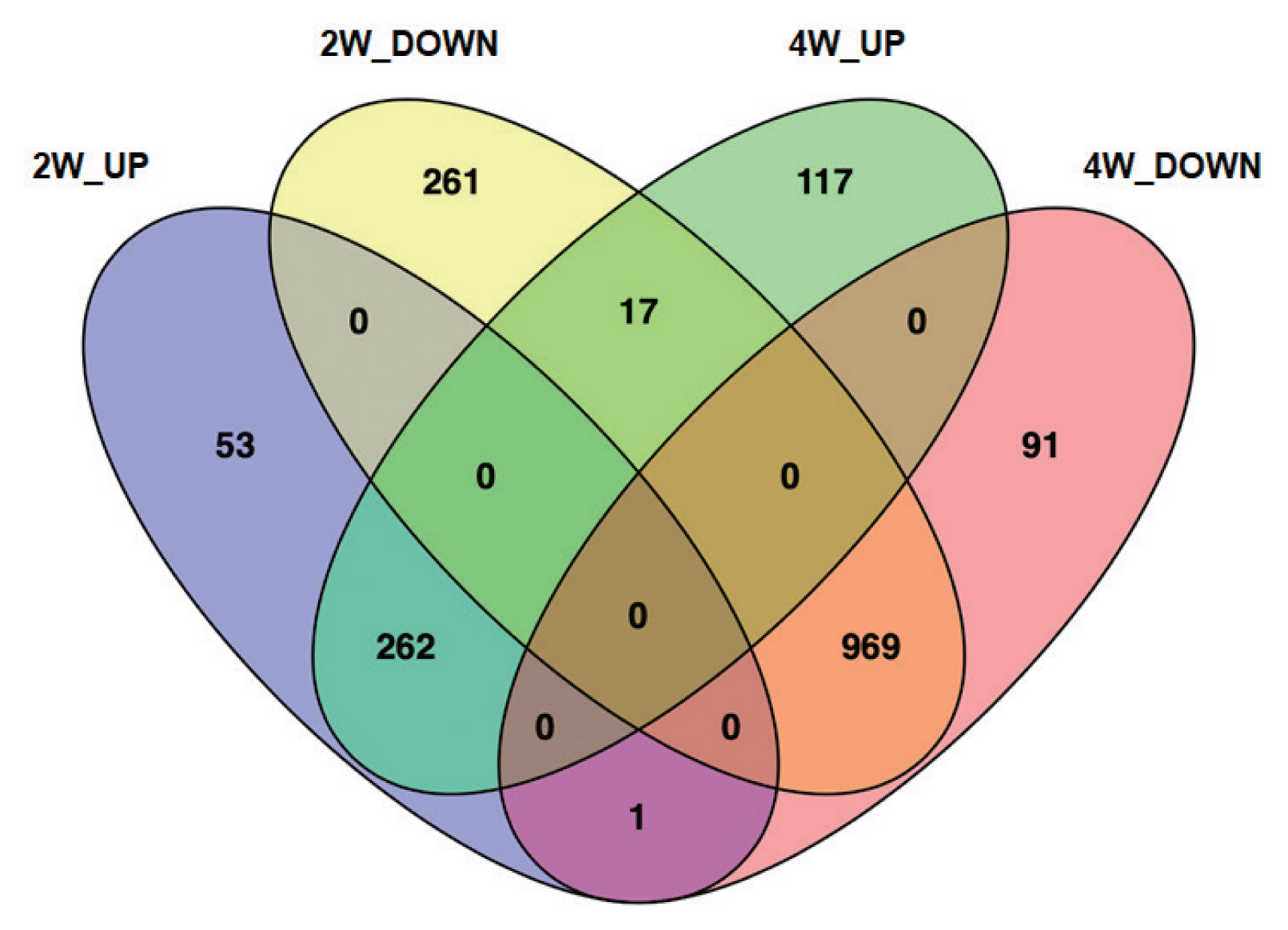

All genes showing monotonically changing expression pattern were further investigated in terms of DEGs and pathway-related genes. The 1,771 DEGs were found to be differently expressed between and among each group as shown in Venn diagrams (

Fig. 4). Compared to NC, 316 genes and 1,247 genes were up-regulated and down-regulated in 2W, respectively. While, 396 genes were up-regulated, but 1,061 ones were down-regulated in 4W compared to NC. Collectively, a majority of DEGs (1,339 genes, 75.6%) were down-regulated in either 2W or 4W. Compared to NC, 314 DEGs (17.7%) were unique to 2W and 208 DEGs (11.7%) were distinctive in 4W. Out of 262 up-regulated DEGs (14.8%) in both 2W and 4W, collagen type IV alpha 6 (

Col4a6; log

2FC=2.40 at 2W and log

2 FC=1.40 at 4W) and collagen type VI alpha 6 (

Col6a6; log

2 FC=2.40 at 2W and log

2FC=1.61 at 4W), were the most highly induced genes by

C. sinensis infection. The infection also induced the expressions of several other genes, such as regenerating islet-derived 3 gamma (

Reg3g), RNase A family 2 (

Rnase2), POU class 2 associating factor 1 (

Pou2af1), MAS-related G-protein coupled receptor member G (RGD1562011), Matrilin 2 (

Matn2), and fibroblast growth factor 2 (

FGF2). Among 969 DEGs (54.7%), which were down-regulated in both 2W and 4W, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (

Glp1r; log

2FC=−2.43 at 2W and log

2FC=−1.03 at 4W) was representative of the most highly-suppressed genes. Several other genes including LOC681282, esophagus cancer-related protein 2 (

Spink7), EP300 interacting inhibitor of differentiation 2B (

Eid2b), acrosin binding protein (

Acrbp) and leucine-rich repeat, and immunoglobulin-like and transmembrane domains 1 (

Lrit1) were also down-regulated, despite their biological functions in

C. sinensis infection are not clear.

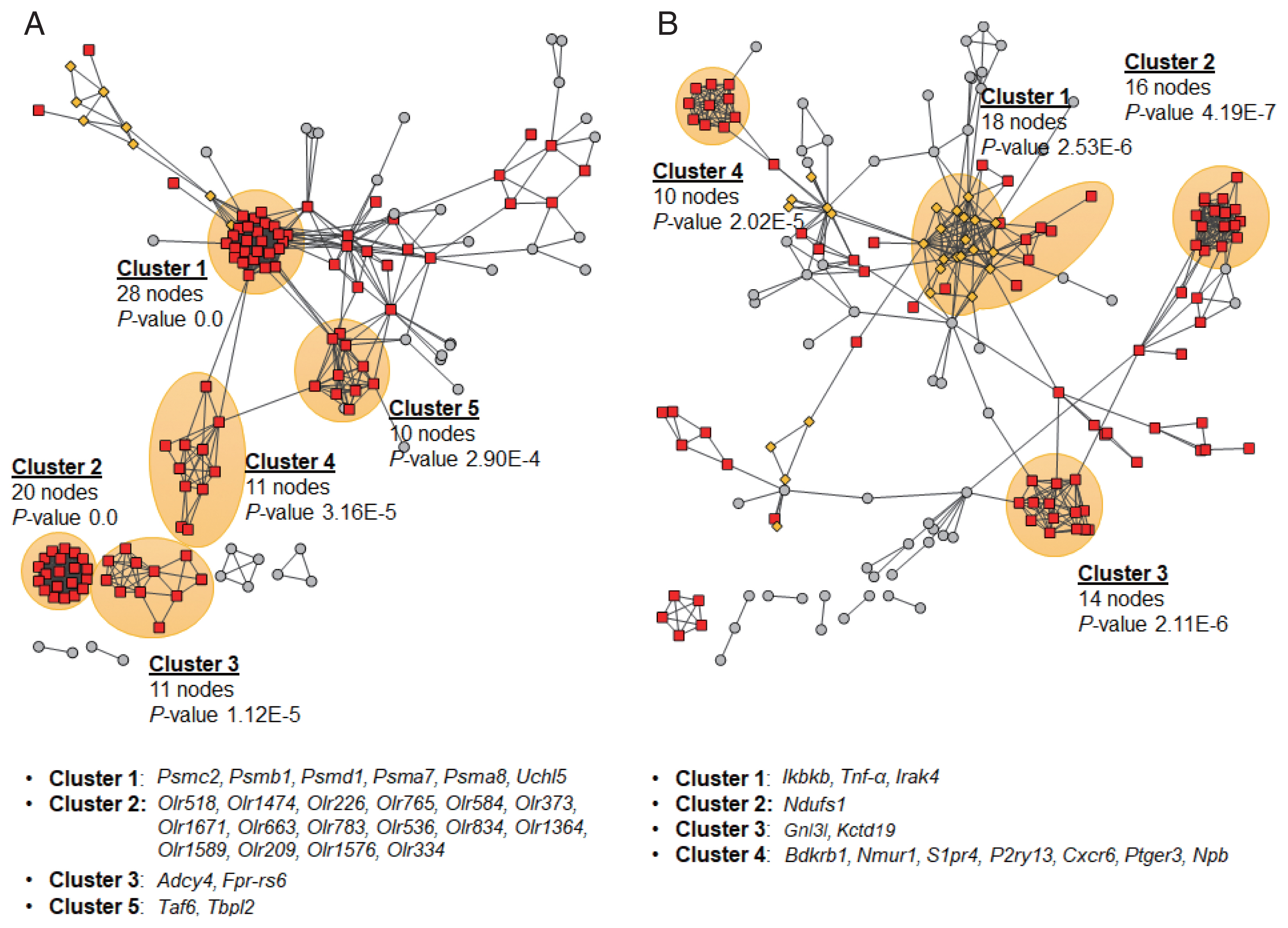

PPIs of DEG products and their neighbors were constructed using STRING database v11.0 [

23] to explore their interactions and sub-networks. PPI networks constructed for the early stage of infection (2W) suggested 5 sub-networks, of which the cluster 1 was significantly linked to important GO cellular components, peptidase complex and proteasome complex (

Fig. 5A). Out of top 400 DEGs, 26 hub genes showed high degree centrality of 8 to 29, which all were down-regulated. Six hub genes,

Psmc2,

Psmb1,

Psmd1,

Taf6,

Tbpl2, and

Mapk1, were key genes with high betweenness centrality of 228 to 1,568. For 4W, 13 hub genes in 4 sub-networks were identified, but no clusters showed any significant enrichment with functional ontologies (

Fig. 5B). Four hub genes,

Gnl3l,

Kctd19,

Bdkrb1, and

Nmur1, were detected as key hub genes with high degree centrality of 8 to 11 and high betweenness centrality of 107 to 2,771.

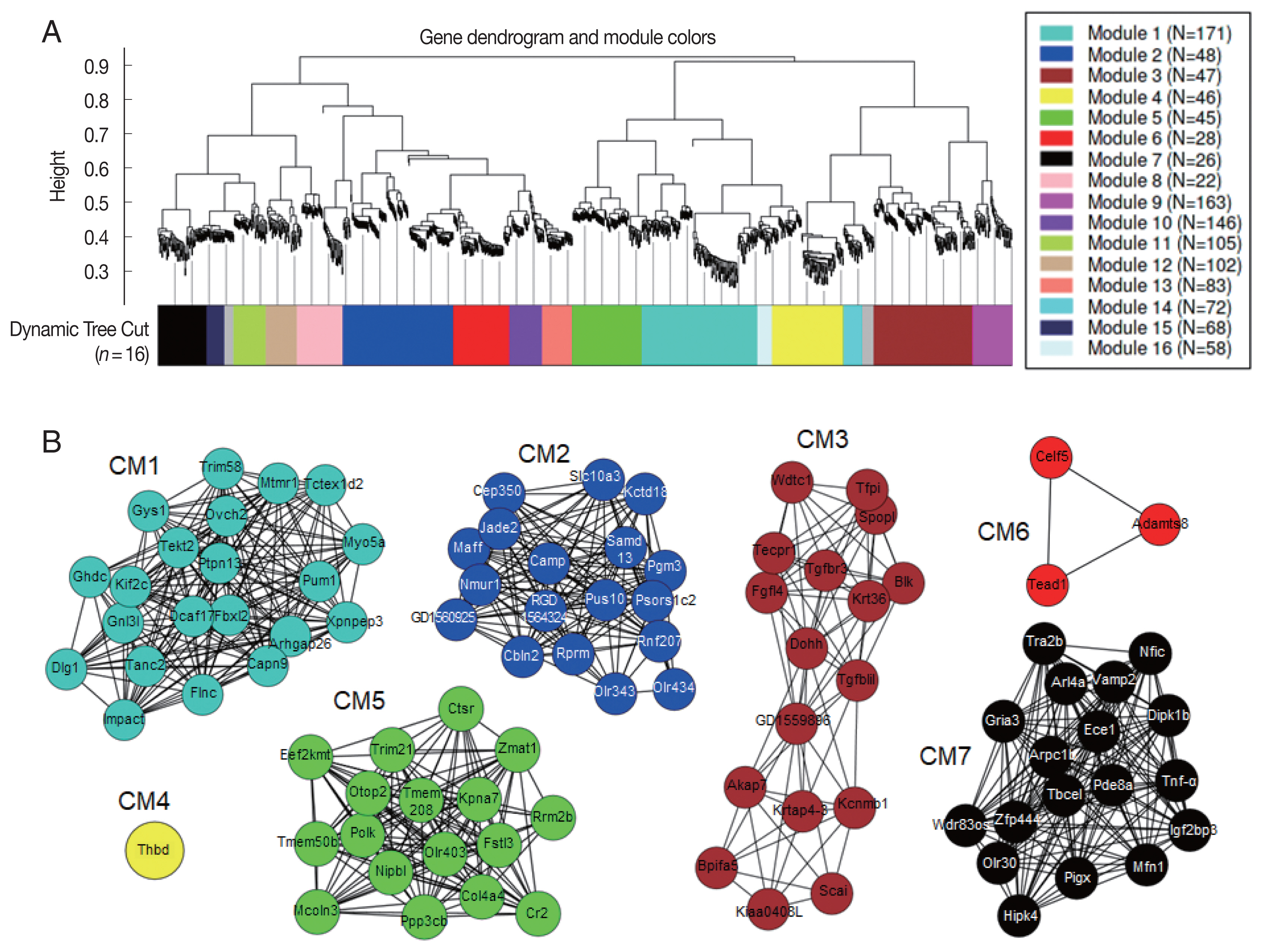

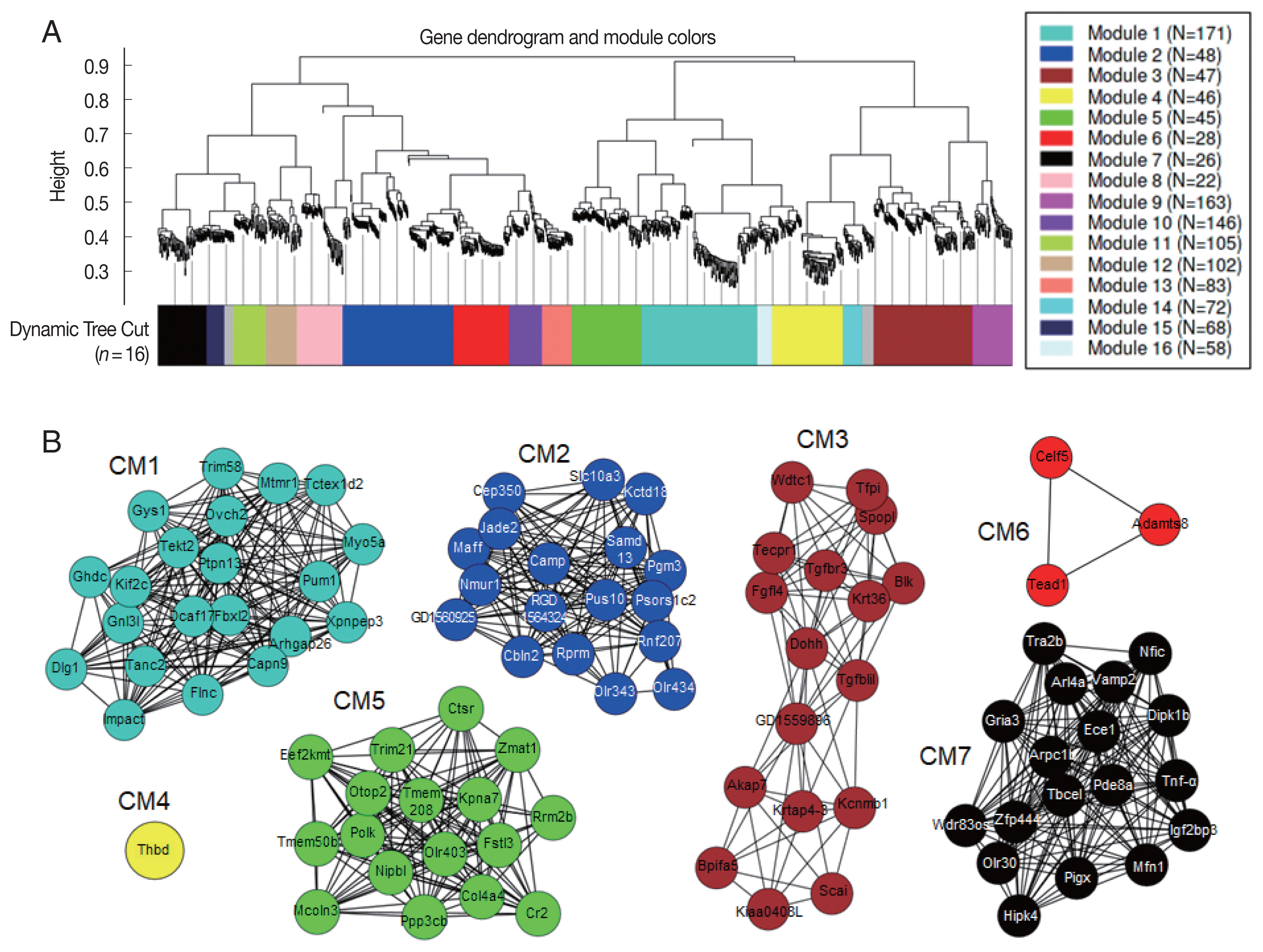

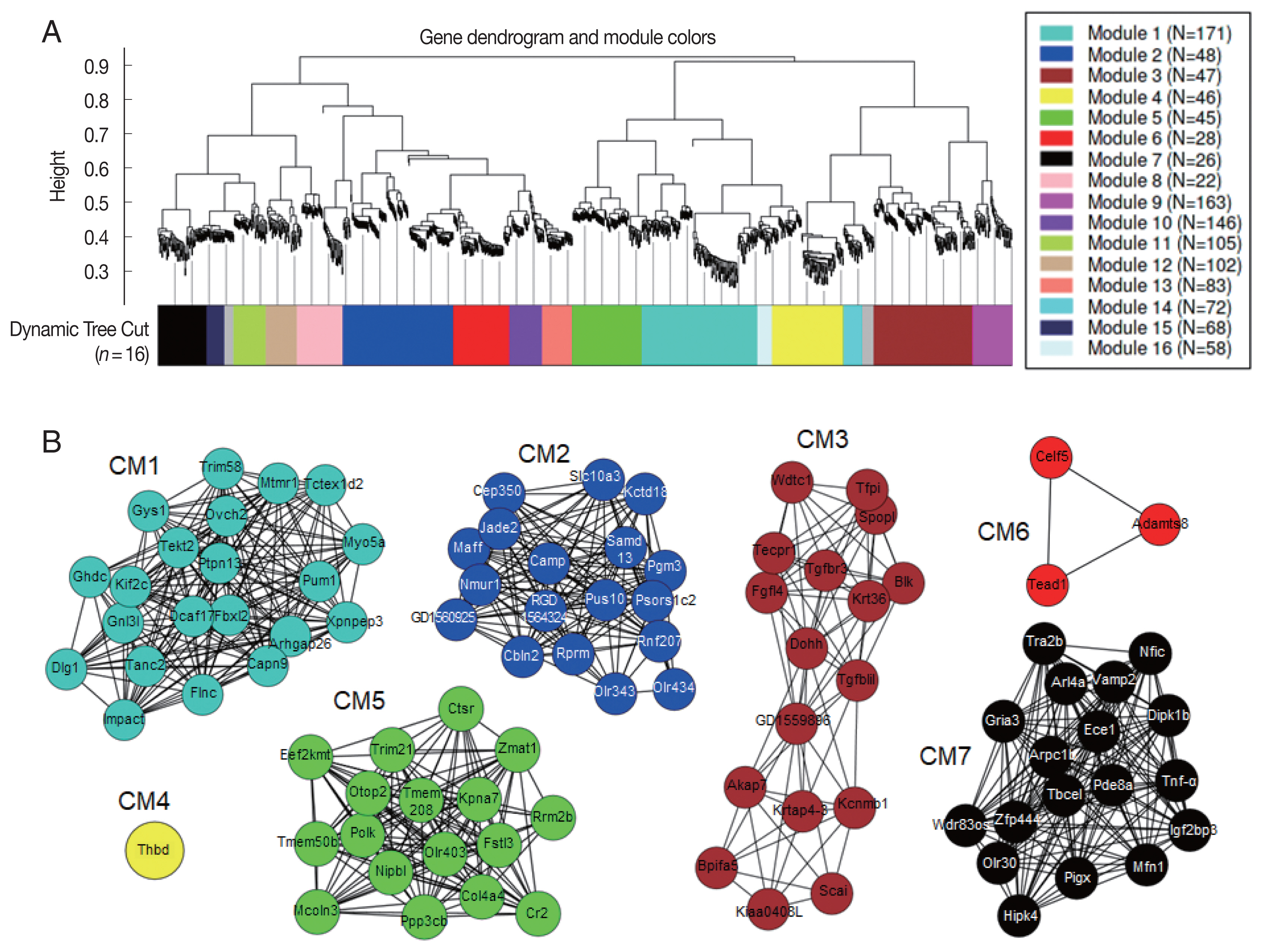

Co-expression network modules analyzed by WGCNA [

30] suggested correlation weighted network based on the gene expression data and gene modules related with the condition under the study. Overall, 1,771 DEGs were arranged into 16 co-expression modules (CM) (

Fig. 6A). Five modules, CM2, CM6, CM10, CM13, and CM14, were identified with significant GO enrichment, suggesting several important biological processes, such as G protein-coupled receptor activity in CM2, sensory perception of chemical stimulus in CM6, signaling receptor activity in CM10, olfactory receptor activity in CM13, and glial cell differentiation in CM14, seemed to be associated with host’s responses against

C. sinensis infection (

Table 2). Although some other modules were also highly correlated, they did not have enough members to pass the significance threshold for GO analysis. A total of 738 hub genes, which had 50 degrees and more, were identified. The 95 hub genes showing MIE or MDE, including 21 genes in CM1, 18 genes in CM2, 17 genes in CM3, 1 gene in CM4, 17 genes in CM5, 3 genes in CM6, and 18 genes in CM7, were finally selected (

Fig. 6B). Among them, 13 key hub genes showed high degree centrality of 97 to 135 and high betweenness centrality of 116 to 372;

Impact,

Mtmr1,

Capn9,

Flnc,

Dcaf17, ENSRNOG00000046969,

Dlg1,

Tanc2, and

Ghdc in CM1,

Dohh, RGD1559896,

Tgfb1i1, and

Ddx19a in CM3.

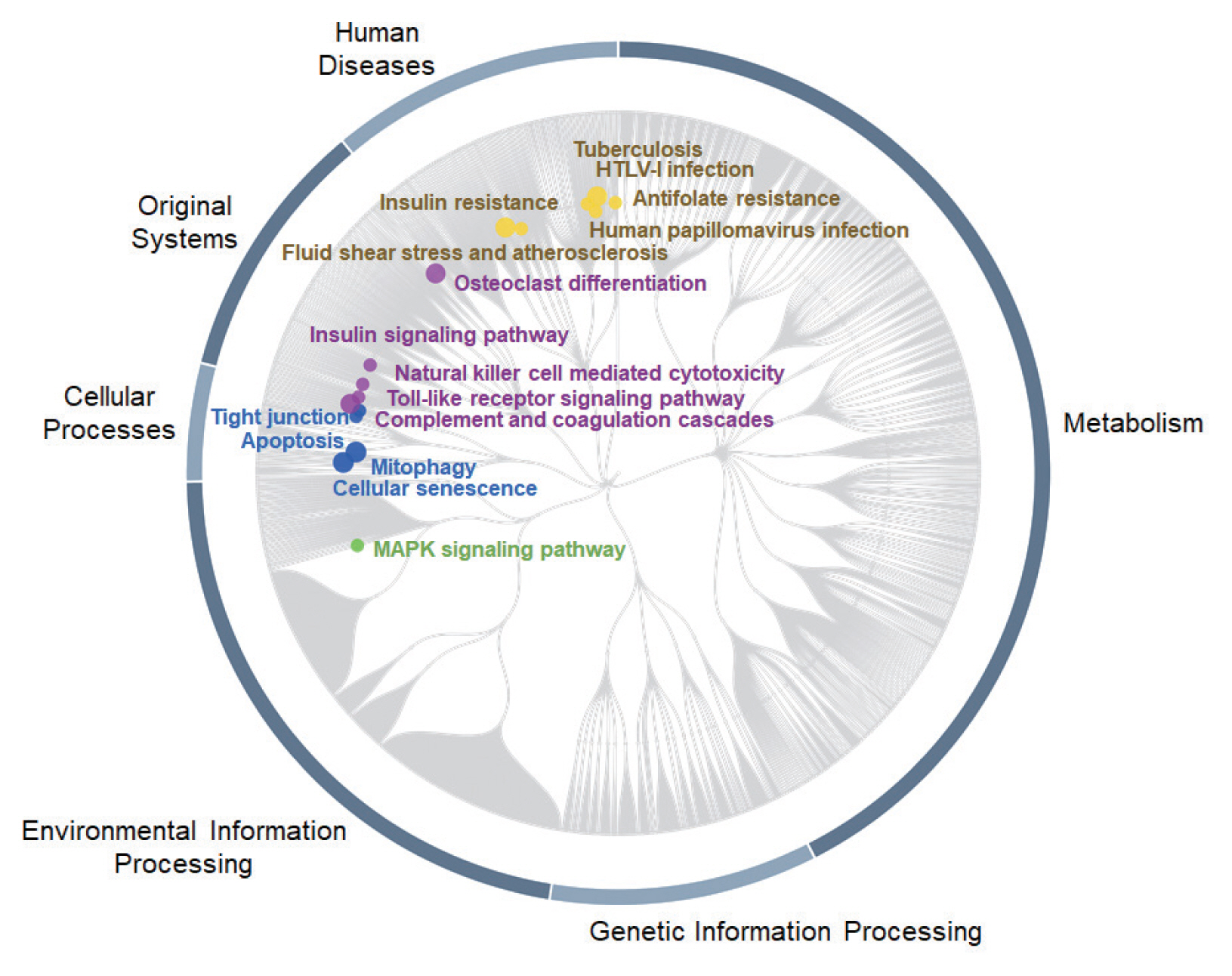

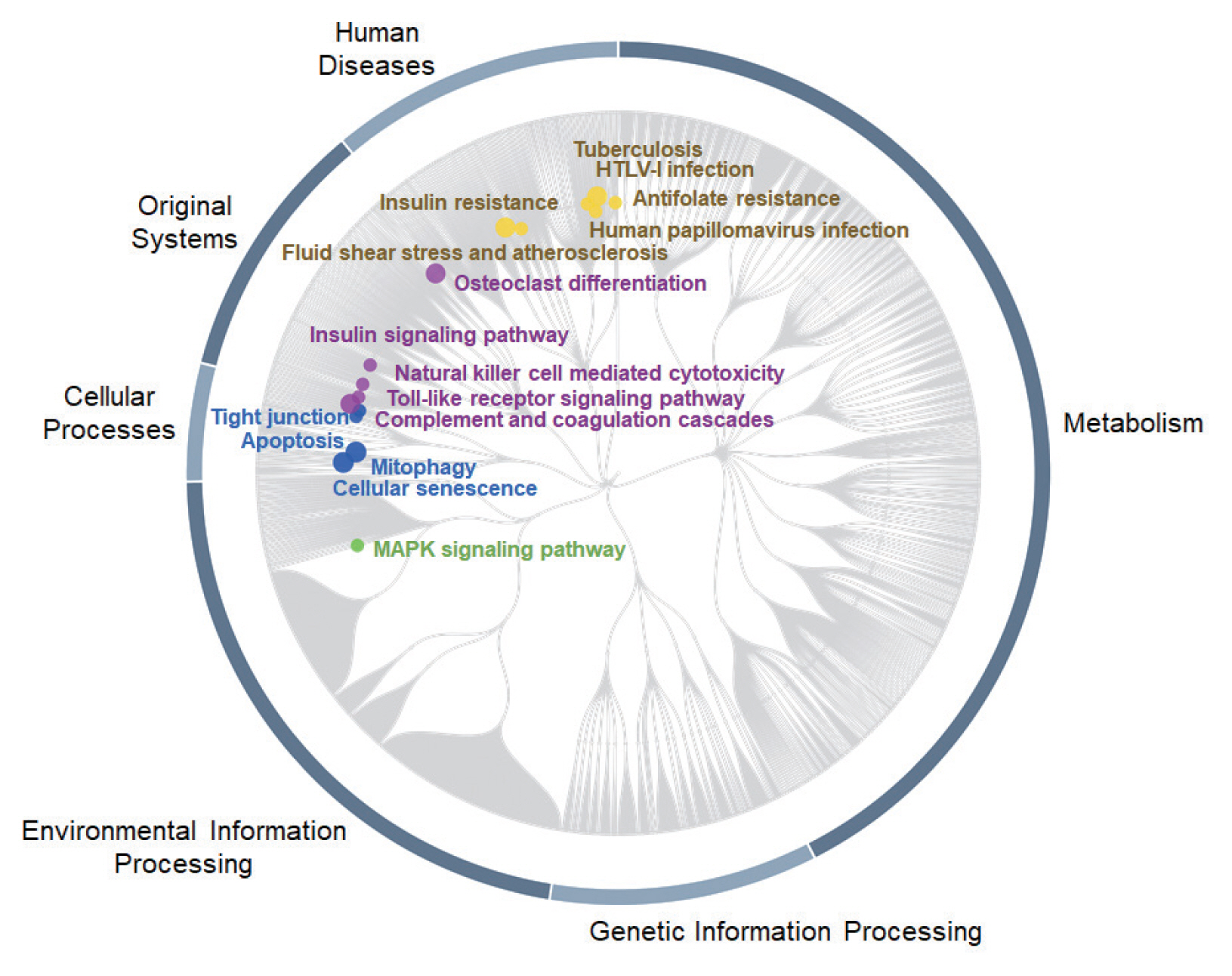

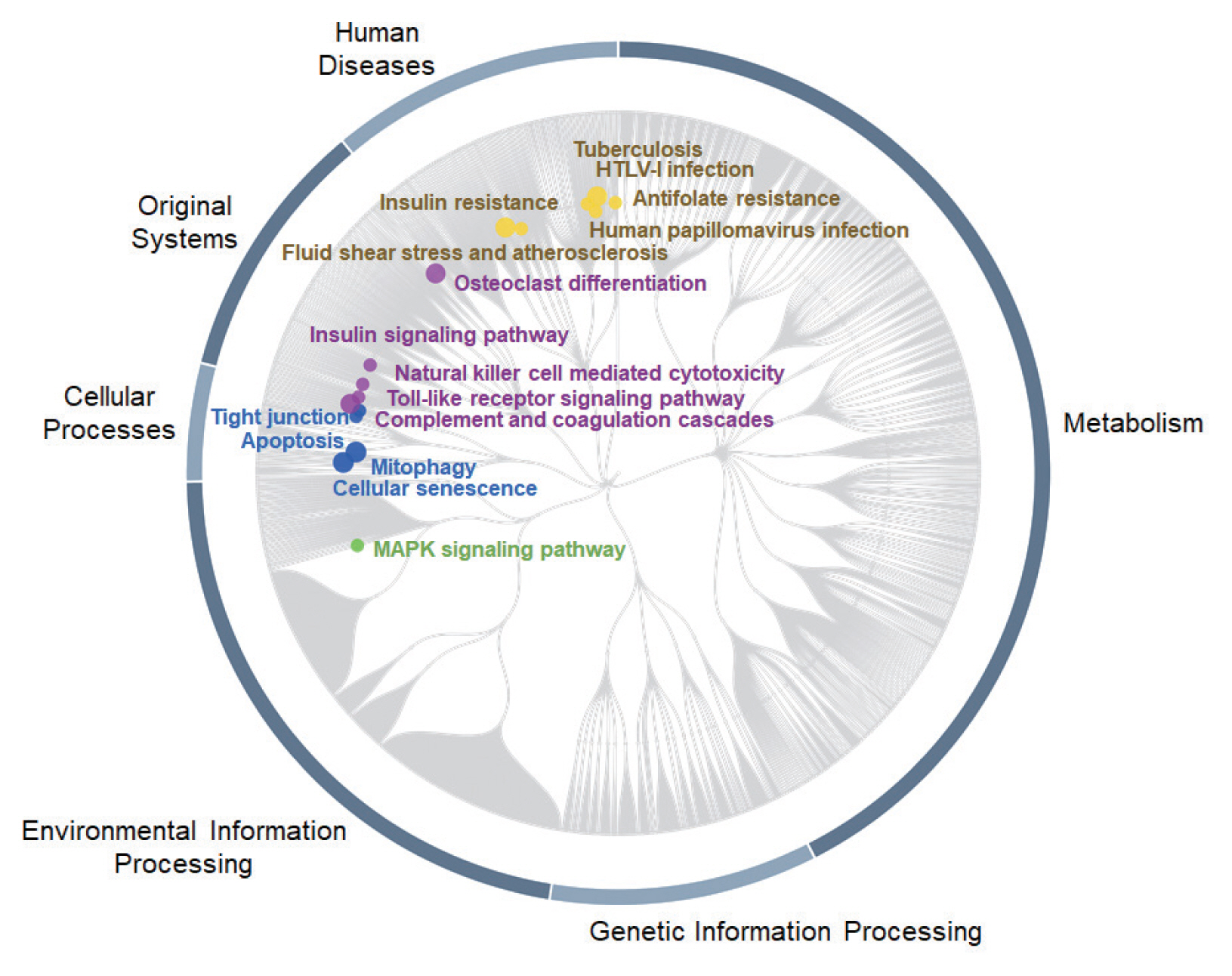

To identify the most important pathways, where 519 DEGs with monotonically changing expression patterns (as a feature list) were statistically enriched, analysis with PaintOmics v3 [

33] was performed. The biological pathways of rats’ bile duct tissues in response to

C. sinensis infection at 2W and 4W were visualized by mapping KO terms assigned by individual DEGs on KEGG pathways. The KEGG pathway gene set analysis of all DEGs showed significant enrichment of 16 pathways, among which 5 pathways were associated with “Original Systems”, 4 pathways with “Cellular Processes”, 6 pathways with “Human Diseases”, and 1 pathway with “Environmental Information Processing” (

Fig. 7). Top 3 key KEGG pathways were human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-I) infection, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection according to the number of nodes. In the MAPK signaling pathway mapped with 28 DEGs, all up-regulated genes were DEGs having MIE.

Cacnb2,

Efna4,

Flt1, and

Ikbkb, which are related with “Classical MAP kinase pathway”, were monotonically up-regulated. High expression of genes associated with “JNK and p38 MAP kinase pathway” such as

Flnc,

Hspa1l, and

Tnf-α, were also identified. Meanwhile, no matched gene for the ERK5 pathway was identified. Viruses infection- and tuberculosis infection-related pathways were also significantly enriched.

Chd4,

Ikbkb,

Itga11,

Tnf-α,

Pik3r2,

Pxn, and

Rbl1, which are related with “HPV infection pathway”, were up-regulated. For “Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection”, most of DEGs were down-regulated, but

Ikbkb,

Tnf-α,

Pik3r2, and

Pold1 were up-regulated in

C. sinensis infection.

DISCUSSION

In this study, transcriptional alterations in bile ducts induced by

C. sinensis infection were analyzed. A majority of DEGs were down-regulated at 2W, suggesting potential pathological changes in the bile ducts start from the early stage of

C. sinensis infection. The DEGs are likely to be temporally dysregulated over the time course of the infection, as evidenced by 699 DEGs of Profiles 32 and 33 in STEM. On the other hand, overall expression patterns at 4W were more similar to those at NC than 2W in the HCL dendrogram, which suggests host’s responses to recover initial pathologic changes in the bile ducts that were induced by the infection operate to maintain functional consequences. Among the most up-regulated DEGs at both infections time points (2W and 4W),

Reg3g and

Rnase2 are likely to be related with defense responses against

C. sinensis infection based on the GO terms, similarly suggested by “defense response to Gram-positive bacterium” (GO:0050830) and “defense response to virus” (GO:0051607).

Reg3g is known as one of inflammatory response genes modulated by

Salmonella infection [

36]. Several Mapk genes such as

Mapk1,

Mapk11, and

Mapk14 have suggested as key genes in response to parasitic infections [

37]. ADP-ribosylation factors including

Arl4a are reported to be up-regulated in

Opisthorchis viverrini-infected hamsters [

38], which was coincided with our results. Increased expressions of the collagen family members in

C. sinensis-infected rat’s bile duct were also in agreement with the previous study that

C. sinensis infection enhanced cell-to-cell communication in the liver tissues of

C. sinensis-infected FVB/N mice [

39].

Out of top down-regulated DEGs at both 2W and 4W, impact of parasitic infection on

Glp1r is not clear, however,

Schistosoma mansoni infection evoked profound alterations in glucagon pathway-related genes at 10 days post-infection in mice [

40].

Glp1r plays a role in the control of glucose and insulin level as a member of gut hormone receptors [

41], and has been considered as a hub gene for both neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction and cAMP signaling pathway [

42]. In addition, under the injured hepatic tissues of rats, GTP-binding proteins and

Blk are reported to be associated with signal transduction [

43] and the inflammatory response [

44], respectively.

The findings in this study are in broad agreement with a previous study, in which a large numbers of DEGs were detected at the early stage of

C. sinensis infection, but only small numbers of DEGs remained up- or down-regulated throughout the time course in FVB/N mouse liver infected with

C. sinensis [

39]. However, our study had several strengths than the previous study [

39]: first, this study applied diverse statistical tests including ANOVA [

17] and

Post-

hoc Tukey’s HSD multiple test [

18] to obtain confident DEGs and to compare across multiple groups in pairwise comparison rather than single Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) [

45]; second, this study applied time-course specific algorithm, STEM [

22], to select DEGs showing monotonically changing expression pattern; and third, this study performed a multi-step integrative bioinformatics analysis to explore the network-based analysis and hub genes/proteins rather than the individual DEGs.

Network approaches to detect sub-networks and key hub genes/proteins that respond to

C. sinensis infection suggested several features in terms of the relationships between DEGs and PPI or WGCNA. DEGs showing MIE or MDE had lower centrality but higher betweenness centrality in PPI networks than in WGCNA. Degree centrality [

46] is a typical centrality measure in characterizing the importance of nodes in a network, suggesting that the greater number of neighbors of a node, the greater influence is predicted. Moreover, the betweenness centrality [

47], which defines the number of shortest paths through the current node in a network, was applied in this study because hub proteins with a higher betweenness tend to be more critical.

From the networks of both PPI and WGCNA, neuromedin-U receptor 1 (

Nmur1; log

2FC=1.82 at 2W and log

2FC=2.30 at 4W) and guanine nucleotide-binding protein-like 3-like protein (

Gnl3l; log

2FC=−1.38 at 2W and log

2FC=−2.27 at 4W) were identified as key hub genes, which haven’t been reported yet in any infection models.

Nmur1 has been reported to play a critical role in stimulating the type 2 cytokines which are important in mediating innate and adaptive defense immune responses against helminth infections and maintaining metabolic homeostasis and repair of damaged tissue [

48]. Worm burden of intestinal nematode

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis is proven to be higher in

Nmur1−/− mice than in

Nmur1+/+ control mice [

49].

Gnl3l has been identified as one of the crucial regulators responsible for the maintenance of the tumorigenic properties and NF-κB signaling-mediated cell survival in humans [

50]. It has reported that free radicals induced by chronic

C. sinensis infection can trigger NF-κB-mediated inflammation in human cholangiocarcinoma cell line [

5]. Therefore,

Nmur1 could be a predictive marker of clonorchiasis in early infection stage, whereas increased expression of

Gnl3l could be used to determine chronic

C. sinensis infection. Further study to investigate these as useful biomarkers would be necessary.

The DEGs were enriched to 16 major canonical KEGG pathways relevant to

C. sinensis infection. These findings are consistent with the previous studies that parasitic infections could contribute to transcriptional alterations of immune system (complement and coagulation cascades [

51], toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway [

51] and natural killer cell/mediated cytotoxicity [

39]), cell growth/death (cellular senescence [

52] and apoptosis [

38]), signal transduction (MAPK signaling pathway [

53]), and endocrine system (insulin signaling pathway [

51]). However, it is worth to mention that the alterations of these pathways may have no biological significance, considering some pathways are often differentially expressed because mammals have a myriad of related genes, such as TLR signaling transducers and MAPK signaling molecules [

54–

57]. The role of TLRs in helminth infections is not clear.

Hymenolepis diminuta induced up-regulations of

Tlr2 and

Tlr4 in the rats’ jejunum in early infection stage [

54]. In this study, monotonical down-regulation of

Tlr7 was observed during

C. sinensis infection, which is consistent with the previous study that

Brugia malayi down-regulated

TLR7 in the host cell [

55].

Mapk1 (a.k.a.

Erk2) and

Mapk8 (a.k.a.

Jnk1) were also significantly down-regulated in the bile ducts of rats infected with

C. sinensis. It has recently reported that expression of MAPK gene members changed by

Echinococcus multilocularis [

56]. In a timely manner, balanced regulation of

ERK1/

2 and

JNK was involved in proliferation and apoptosis of hepatocyte, respectively, because two signaling molecules belong to different MAPK pathway subgroups, such as growth factors and external stimuli [

57]. In particular,

Tnf-α was concurrently enriched in 11 KEGG pathways and regarded as a monotonically up-regulated gene but not a key hub gene/protein. It is proposed that

Tnf-α may play a major role in inflammatory response in bile epithelial cells in clonorchiasis [

7]. Biological significances of regulated expressions of these genes above should be investigated further throughout the prolonged period of

C. sinensis infection. These findings may provide new insights to understand for host dynamics against

C. sinensis infection.

In conclusion, analysis of comprehensive transcriptomic profiles in rats’ bile duct provided useful information for understanding the pathological changes of bile ducts during initial infection phases of C. sinensis. A total of 1,771 DEGs, which revealed highly dynamic and time-dependent expression patterns, were detected and 519 of them showed monotonically changing expression patterns in the infected rats. PPIs of the DEG products and co-expression networks of the DEGs suggested 10 key hub proteins and 13 key hub genes, respectively. All DEGs were enriched to a set of 16 key KEGG pathways which are essential to immune response and signal transduction for host defense against parasitic infection. Our results could facilitate future studies to uncover molecular pathogenic mechanism of clonorchiasis and to identify a set of diagnostic marker candidates for early detection of C. sinensis infection. However, this study also had a limitation in that the numbers of bile ducts analyzed in this study were not sufficient to generalize. Despite this limitation, this is the first trial to understand molecular pathobiological events in bile ducts induced by C. sinensis via a microarray-based methodology. Further study is necessary to evaluate the potential biomarkers identified in this study as reliable ones for early diagnosis clonorchiasis. Moreover, more comprehensive study is needed to investigate pathobiological changes in the bile ducts of C. sinensis infected host for in-depth understanding the pathology of the carcinogenic parasite.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interests related to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (Grant No. NRF2016R1C1B1009348 and NRF2018R1C1B6005581).

Fig. 1A workflow of this study.

Fig. 2Unsupervised discrimination of different groups based on rat bile duct gene expression profiles. All sample groups were discriminated clearly based on the DEGs using (A) principal components analysis (PCA) and (B) hierarchical clustering (HCL). The dendrograms were generated based on HCL of correlation distance between individual microarray expression profiles. NC, normal control; 2W and 4W, 2 and 4 weeks post-infection with C. sinensis.

Fig. 3Time series-based gene expression patterns at early and late infection groups. All of 1,771 DEGs were analyzed using STEM [

22]. Black lines indicated expression patterns of 40 model profiles while red lines represented expressions of all genes. NC, normal control, 2W, 2 weeks, and 4W, 4 weeks. Significant profiles were colored, and similar colors meant the same cluster of model profiles. Numbers on the top left and bottom left correspond to the numbers of profiles and the associated

P-value, respectively. Profiles were ordered based on the

P-value significance of numbers of genes assigned (on the top right) versus expected.

Fig. 4A Venn diagram showing DEGs in the bile ducts infected with C. sinensis. 2W and 4W, 2 and 4 weeks post-infection with C. sinensis. Purple, yellow, green and magenta colors denote 2W_UP, 2W_DOWN, 4W_UP, and 4W_DOWN, respectively.

Fig. 5Protein-protein interactions and sub-networks of DEG products. The networks were constructed using each top 400 DEG products and no more than 50 interactors from the 2 week (A) and 4 week groups (B) using STRING database v11.0 [

23]. The most significant sub-networks were shaded in orange and the hub genes of each sub-network were provided below each network.

Fig. 6Correlation dendrogram and modules identified by co-expression network in the

C. sinensis-infected rat’s bile ducts. (A) Based on gene expression pattern, WGCNA [

30] identified a network of 1,771 genes divided into 16 co-expression modules (CM). Only hub genes showing monotonically changing expression patterns were displayed. The genes in the same module were the same colors, but grey color indicated outliers or uncharacterized genes. (B) Genes were represented as nodes and each node was connected to other nodes in the weighted network.

Fig. 7Top 16 significantly enriched KEGG pathways. The pathway enrichment analysis was carried out using PaintOmics v3 [

33]. Nodes were labeled only for the KEGG pathways and the diameter of each node circle was proportional to

P-value.

Table 1

Post-hoc Tukey HSD results showing multiple comparisons (n=2,895)

Table 1

|

Treatments pair |

Tukey HSD |

|

Q statistic |

P-value |

Inference*

|

|

NC vs 2W |

69.620 |

0.001 |

Significant |

|

NC vs 4W |

35.705 |

0.001 |

Significant |

|

W2 vs 4W |

33.915 |

0.001 |

Significant |

Table 2Co-expression modules associated with C. sinensis infection among DEGs

Table 2

|

Co-expression module (CM) |

Gene set name |

P-value |

No. of genes |

|

CM2 |

G protein-coupled receptor activity |

1.60E-04 |

35 |

|

Transmembrane signaling activity |

9.70E-04 |

36 |

|

Sensory perception of chemical stimulus |

8.70E-03 |

24 |

|

Detection of stimulus involved in sensory perception |

8.70E-03 |

24 |

|

|

CM6 |

Sensory perception of chemical stimulus |

2.60E-05 |

20 |

|

Olfactory receptor activity |

2.60E-05 |

19 |

|

Nervous system process |

1.10E-02 |

3 |

|

Olfactory transduction |

2.20E-04 |

16 |

|

G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway |

6.80E-04 |

22 |

|

Transmembrane signaling receptor activity |

6.90E-04 |

22 |

|

G protein-coupled receptor activity |

7.70E-04 |

20 |

|

System process |

7.80E-04 |

24 |

|

|

CM10 |

Signaling receptor activity |

6.00E-03 |

16 |

|

Transmembrane signaling receptor activity |

7.40E-03 |

15 |

|

|

CM13 |

Olfactory receptor activity |

8.80E-03 |

10 |

|

Olfactory transduction |

8.80E-03 |

9 |

|

Sensory perception |

8.80E-03 |

12 |

|

|

CM14 |

Glial cell differentiation |

4.40E-03 |

4 |

|

Cell proliferation in hindbrain |

4.40E-03 |

2 |

|

Gliogenesis |

4.40E-03 |

5 |

References

- 1. Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States Part III: Liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology 2009;136:1134-1144.

- 2. . Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori

. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon: 7–14 June 1994; IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994. 61:1-241.

- 3. Sawanyawisuth K, Wongkham C, Araki N, Zhao Q, Riggins GJ, Wongkham S. Serial analysis of gene expression reveals promising therapeutic targets for liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13(suppl):89-93.

- 4. Yongvanit P, Pinlaor S, Bartsch H. Oxidative and nitrative DNA damage: key events in opisthorchiasis-induced carcinogenesis. Parasitol Int 2012;61:130-135.

- 5. Pak JH, Kim DW, Moon JH, Nam JH, Kim JH, Ju JW, Kim TS, Seo SB. Differential gene expression profiling in human cholangiocarcinoma cells treated with Clonorchis sinensis excretory-secretory products. Parasitol Res 2009;104:1035-1046.

- 6. Pak JH, Lee JY, Jeon BY, Dai F, Yoo WG, Hong SJ. Cytokine Production in Cholangiocarcinoma Cells in Response to Clonorchis sinensis Excretory-Secretory Products and Their Putative Protein Components. Korean J Parasitol 2019;57:379-387.

- 7. Kang JM, Yoo WG, Le HG, Lee J, Sohn WM, Na BK.

Clonorchis sinensis MF6p/HDM (CsMF6p/HDM) induces pro-inflammatory immune response in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells via NF-kappaB-dependent MAPK pathways. Parasit Vectors 2020;13:20.

- 8. Rahman SM, Bae YM, Hong ST, Choi MH. Early detection and estimation of infection burden by real-time PCR in rats experimentally infected with Clonorchis sinensis

. Parasitol Res 2011;109:297-303.

- 9. Rahman SMM, Song HB, Jin Y, Oh JK, Lim MK, Hong ST, Choi MH. Application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay targeting cox1 gene for the detection of Clonorchis sinensis in human fecal samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11:e0005995.

- 10. Pan XH. Pathway crosstalk analysis based on protein-protein network analysis in ovarian cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:3905-3909.

- 11. Na BK, Kang JM, Sohn WM. CsCF-6, a novel cathepsin F-like cysteine protease for nutrient uptake of Clonorchis sinensis

. Int J Parasitol 2008;38:493-502.

- 12. Kang JM, Bahk YY, Cho PY, Hong SJ, Kim TS, Sohn WM, Na BK. A family of cathepsin F cysteine proteases of Clonorchis sinensis is the major secreted proteins that are expressed in the intestine of the parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2010;170:7-16.

- 13. Alonso R, Salavert F, Garcia-Garcia F, Carbonell-Caballero J, Bleda M, Garcia-Alonso L, Sanchis-Juan A, Perez-Gil D, Marin-Garcia P, Sanchez R, Cubuk C, Hidalgo MR, Amadoz A, Hernansaiz-Ballesteros RD, Aleman A, Tarraga J, Montaner D, Medina I, Dopazo J. Babelomics 5.0: functional interpretation for new generations of genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:W117-121.

- 14. Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 2002;30:207-210.

- 15. Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 2003;19:185-193.

- 16. Ulitsky I, Maron-Katz A, Shavit S, Sagir D, Linhart C, Elkon R, Tanay A, Sharan R, Shiloh Y, Shamir R. Expander: from expression microarrays to networks and functions. Nat Protoc 2010;5:303-322.

- 17. Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, Sturn A, Snuffin M, Rezantsev A, Popov D, Ryltsov A, Kostukovich E, Borisovsky I, Liu Z, Vinsavich A, Trush V, Quackenbush J. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 2003;34:374-378.

- 18. Copenhaver MD, Holland B. Computation of the distribution of the maximum studentized range statistic with application to multiple significance testing of simple effects. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 1988;30:1-15.

- 19. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:e47.

- 20. Ge SX, Son EW, Yao R. iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 2018;19:534.

- 21. Mudunuri U, Che A, Yi M, Stephens RM. bioDBnet: the biological database network. Bioinformatics 2009;25:555-556.

- 22. Ernst J, Bar-Joseph Z. STEM: a tool for the analysis of short time series gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics 2006;7:191.

- 23. Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M, Wyder S, Simonovic M, Santos A, Doncheva NT, Roth A, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45(D1):362-368.

- 24. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003;13:2498-2504.

- 25. Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J, Jensen LJ. Cytoscape StringApp: Network Analysis and Visualization of Proteomics Data. J Proteome Res 2019;18:623-632.

- 26. Nepusz T, Yu H, Paccanaro A. Detecting overlapping protein complexes in protein-protein interaction networks. Nat Methods 2012;9:471-472.

- 27. Mlecnik B, Galon J, Bindea G. Automated exploration of gene ontology term and pathway networks with ClueGO-REST. Bioinformatics 2019;35:3864-3866.

- 28. Bindea G, Galon J, Mlecnik B. CluePedia Cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics 2013;29:661-663.

- 29. Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol 2014;8(Suppl 4):S11.

- 30. Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008;9:559.

- 31. Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA package FAQ 2017.

- 32. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:15545-15550.

- 33. Hernandez-de-Diego R, Tarazona S, Martinez-Mira C, Balzano-Nogueira L, Furio-Tari P, Pappas GJ Jr, Conesa A. PaintOmics 3: a web resource for the pathway analysis and visualization of multi-omics data. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(W1):503-509.

- 34. Furnham N, Sillitoe I, Holliday GL, Cuff AL, Rahman SA, Laskowski RA, Orengo CA, Thornton JM. FunTree: a resource for exploring the functional evolution of structurally defined enzyme superfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(D1):776-782.

- 35. Zerbino DR, Achuthan P, Akanni W, Amode MR, Barrell D, Bhai J, Billis K, Cummins C, Gall A, Girón CG, Gil L, Gordon L, Haggerty L, Haskell E, Hourlier T, Izuogu OG, Janacek SH, Juettemann T, To JK, Laird MR, Lavidas I, Liu Z, Loveland JE, Maurel T, McLaren W, Moore B, Mudge J, Murphy DN, Newman V, Nuhn M, Ogeh D, Ong CK, Parker A, Patricio M, Riat HS, Schuilenburg H, Sheppard D, Sparrow H, Taylor K, Thormann A, Vullo A, Walts B, Zadissa A, Frankish A, Hunt SE, Kostadima M, Langridge N, Martin FJ, Muffato M, Perry E, Ruffier M, Staines DM, Trevanion SJ, Aken BL, Cunningham F, Yates A, Flicek P. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(D1):754-761.

- 36. Rodenburg W, Keijer J, Kramer E, Roosing S, Vink C, Katan MB, van der Meer R, Bovee-Oudenhoven IM. Salmonella induces prominent gene expression in the rat colon. BMC Microbiol 2007;7:84.

- 37. Han H, Peng J, Hong Y, Zhang M, Han Y, Fu Z, Shi Y, Xu J, Tao J, Lin J. Comparison of the differential expression miRNAs in Wistar rats before and 10 days after S. japonicum infection. Parasit Vectors 2013;6:120.

- 38. Wu Z, Boonmars T, Boonjaraspinyo S, Nagano I, Pinlaor S, Puapairoj A, Yongvanit P, Takahashi Y. Candidate genes involving in tumorigenesis of cholangiocarcinoma induced by Opisthorchis viverrini infection. Parasitol Res 2011;109:657-673.

- 39. Kim DM, Ko BS, Ju JW, Cho SH, Yang SJ, Yeom YI, Kim TS, Won Y, Kim IC. Gene expression profiling in mouse liver infected with Clonorchis sinensis metacercariae. Parasitol Res 2009;106:269-278.

- 40. Cortes-Selva D, Elvington AF, Ready A, Rajwa B, Pearce EJ, Randolph GJ, Fairfax KC.

Schistosoma mansoni Infection-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Hepatic Macrophage Metabolism Correlate With an Athero-Protective Phenotype. Front Immunol 2018;9:2580.

- 41. Jiang M, Zeng Q, Dai S, Liang H, Dai F, Xie X, Lu K, Gao C. Comparative analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis gene expression profiles. Mol Med Rep 2017;15:380-386.

- 42. Kashyap S, Kumar S, Agarwal V, Misra DP, Phadke SR, Kapoor A. Protein protein interaction network analysis of differentially expressed genes to understand involved biological processes in coronary artery disease and its different severity. Gene Reports 2018;12:50-60.

- 43. Sharma MR, Polavarapu R, Roseman D, Patel V, Eaton E, Kishor PB, Nanji AA. Increased severity of alcoholic liver injury in female verses male rats: a microarray analysis. Exp Mol Pathol 2008;84:46-58.

- 44. Yang Q, Mattick JS, Orman MA, Nguyen TT, Ierapetritou MG, Berthiaume F, Androulakis IP. Dynamics of hepatic gene expression profile in a rat cecal ligation and puncture model. J Surg Res 2012;176:583-600.

- 45. Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:5116-5121.

- 46. Sabidussi G. The centrality index of a graph. Psychometrika 1966;31:581-603.

- 47. Freeman LC. A Set of Measures of Centrality Based on Betweenness. Sociometry 1977;40:35-41.

- 48. Klose CSN, Mahlakoiv T, Moeller JB, Rankin LC, Flamar AL, Kabata H, Monticelli LA, Moriyama S, Putzel GG, Rakhilin N, Shen X, Kostenis E, Konig GM, Senda T, Carpenter D, Farber DL, Artis D. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature 2017;549:282-286.

- 49. Cardoso V, Chesne J, Ribeiro H, Garcia-Cassani B, Carvalho T, Bouchery T, Shah K, Barbosa-Morais NL, Harris N, Veiga-Fernandes H. Neuronal regulation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells via neuromedin U. Nature 2017;549:277-281.

- 50. Thoompumkal IJ, Rehna K, Anbarasu K, Mahalingam S. Leucine Zipper Down-regulated in Cancer-1 (LDOC1) interacts with Guanine nucleotide binding protein-like 3-like (GNL3L) to modulate Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-kappaB) signaling during cell proliferation. Cell Cycle 2016;15:3251-3267.

- 51. Airas N, Nareaho A, Linden J, Valo E, Hautaniemi S, Jokelainen P, Sukura A. Early Trichinella spiralis and Trichinella nativa infections induce similar gene expression profiles in rat jejunal mucosa. Exp Parasitol 2013;135:363-369.

- 52. Mayer DA, Fried B. The role of helminth infections in carcinogenesis. Adv Parasitol 2007;65:239-296.

- 53. Lin R, Lu G, Wang J, Zhang C, Xie W, Lu X, Mantion G, Martin H, Richert L, Vuitton DA, Wen H. Time course of gene expression profiling in the liver of experimental mice infected with Echinococcus multilocularis

. PLoS One 2011;6:e14557.

- 54. Kosik-Bogacka DI, Wojtkowiak-Giera A, Kolasa A, Salamatin R, Jagodzinski PP, Wandurska-Nowak E.

Hymenolepis diminuta: analysis of the expression of Toll-like receptor genes (TLR2 and TLR4) in the small and large intestines of rats. Exp Parasitol 2012;130:261-266.

- 55. Semnani RT, Venugopal PG, Leifer CA, Mostbock S, Sabzevari H, Nutman TB. Inhibition of TLR3 and TLR4 function and expression in human dendritic cells by helminth parasites. Blood 2008;112:1290-1298.

- 56. Zhang C, Wang J, Lu G, Li J, Lu X, Mantion G, Vuitton DA, Wen H, Lin R. Hepatocyte proliferation/growth arrest balance in the liver of mice during E. multilocularis infection: a coordinated 3-stage course. PLoS One 2012;7:e30127.

- 57. Zhao Y, Gui W, Niu F, Chong S. The MAPK Signaling Pathways as a Novel Way in Regulation and Treatment of Parasitic Diseases. Diseases 2019;7:9.

, Woon-Mok Sohn2, Byoung-Kuk Na2,3,*

, Woon-Mok Sohn2, Byoung-Kuk Na2,3,*