Sirtinol Supresses Trophozoites Proliferation and Encystation of Acanthamoeba via Inhibition of Sirtuin Family Protein

Article information

Abstract

The encystation of Acanthamoeba leads to the development of metabolically inactive and dormant cysts from vegetative trophozoites under unfavorable conditions. These cysts are highly resistant to anti-Acanthamoeba drugs and biocides. Therefore, the inhibition of encystation would be more effective in treating Acanthamoeba infection. In our previous study, a sirtuin family protein—Acanthamoeba silent-information regulator 2-like protein (AcSir2)—was identified, and its expression was discovered to be critical for Acanthamoeba castellanii proliferation and encystation. In this study, to develop Acanthamoeba sirtuin inhibitors, we examine the effects of sirtinol, a sirtuin inhibitor, on trophozoite growth and encystation. Sirtinol inhibited A. castellanii trophozoites proliferation (IC50=61.24 μM). The encystation rate of cells treated with sirtinol significantly decreased to 39.8% (200 μM sirtinol) after 24 hr of incubation compared to controls. In AcSir2-overexpressing cells, the transcriptional level of cyst-specific cysteine protease (CSCP), an Acanthamoeba cysteine protease involved in the encysting process, was 11.6- and 88.6-fold higher at 48 and 72 hr after induction of encystation compared to control. However, sirtinol suppresses CSCP transcription, resulting that the undegraded organelles and large molecules remained in sirtinol-treated cells during encystation. These results indicated that sirtinol sufficiently inhibited trophozoite proliferation and encystation, and can be used to treat Acanthamoeba infections.

INTRODUCTION

Acanthamoeba is an opportunistic human pathogen that causes granulomatous amebic encephalitis, dermatitis, and amebic keratitis. Its life cycle comprises both trophozoites and cysts [1,2]. Under conditions unfavorable to the growth of Acanthamoeba, vegetative trophozoites are metabolically inactivated and become dormant cysts through encystation to maintain survival [3–6]. Thus, suppression of encystation during the treatment of Acanthamoeba infection may yield more favorable clinical outcomes. In our previous study, we identified the sirtuin (SIR2) family protein, Acanthamoeba silent-information regulator 2-like protein (AcSir2), and found that the regulation of its expression was critical for Acanthamoeba castellanii proliferation and encystation [7]. AcSir2 overexpression leads to increased cell growth in A. castellanii trophozoites and accelerated encystation. Sirtuins regulate a variety of transcription factors and coregulators such as p53, FOXOs (forkhead box subgroup O), PPARs (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors), and NF-κB through the deacetylation and act as a sensor of energetic status that interprets the external changes and regulates the internal responses at a subcellular level [8–10]. Sirtuin family members (SIRT1 to SIRT7), which have different subcellular localization [11] and protein substrates, are involved in various critical cellular processes, including transcription, DNA repair, metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, and stress resistance [12,13]. Salermide, as a sirtuin inhibitor, suppresses not only proliferation but also the encysting process of trophozoites by inhibiting cellulose synthase (CS) transcription, which is essential for cyst wall formation. Thus, AcSir2 expression highlights its value as a therapeutic target, and its inhibitor is critical for developing anti-Acanthamoeba reagents. In this study, we examine the effects of sirtinol (2-[(2-Hydroxynaphthalen-1-ylmethylene)amino]-N-(1-phenethyl)benzamide), another sirtuin inhibitor, on trophozoite growth and encystation, and observe whether sirtinol can be used to treat Acanthamoeba infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Acanthamoeba castellanii Cultures and the Induction of Encystation

The Acanthamoeba castellanii Neff strain (ATCC #30010) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in peptone-yeast-glucose medium at 25°C, as previously described [14]. According to a previous study with slight modifications, the encystation of Acanthamoeba was induced [15]. Briefly, from the post-logarithmic growth phase, 1×106 cells of A. castellanii trophozoites were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated in 10 ml of encystment medium (95 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM NaHCO3, and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0) at 25°C for 72 hr.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was conducted in AcSir2-overexpressing [7] or control cells using an Eco Real-Time PCR system (Illumina, SD, USA): 10 min of pre-incubation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C with CS-(sense: 5′-TCATCTACATGTTCTGCGCCC-3′; antisense: 5′-CGATCCAGTTGTTGTTGAGCATGC-3′) or CSCP-specific primers (sense: 5′-AACAGCACGCTCGTTTCCCTCT-3′; antisense: 5′-GTAGTTGGCCTCCGTCATGAGCTT-3′). The relative amounts were calculated and normalized using Acanthamoeba actin as an internal standard (GenBank: CAA23399) [16] (sense primer: 5′-AGGTCATCACCATCGGTA ACG-3′; antisense primer: 5′-TCGCACTTCATGATCGAGTTG-3′), as previously described [17].

Proliferation and Encystation Assays

The effect of the sirtuin inhibitor, sirtinol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), on the proliferation and encystation of Acanthamoeba was determined according to a previous study [7]. First, 3×105 cells/well of trophozoites were seeded into 6-well plates containing 3 ml of encystment medium, treated with sirtinol, and incubated at 25°C for 24, 48, and 72 hr. The sirtinol was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −20°C until further use. The same amount of DMSO was used in the final solutions of sirtinol as a control. After incubation with sirtinol or DMSO, the cells were stained with trypan blue and observed under a microscope. For the encystation suppression assays, encystment was induced and the change from trophozoites to cysts was observed under a light microscope. The encystation ratio was calculated by counting the cysts using a hemocytometer under a light microscope after treating the cells with 0.5% sarkosyl and 0.4% trypan blue [18–20].

Transmission Electron Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, the cells treated with DMSO or sirtinol were prepared according to a previous study with slight modifications [17].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance and Student’s t-tests with GraphPad Prism 8.2 software (GraphPad, San Diego, USA). Significant group differences were observed using Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison tests or Bonferroni correction. P<0.01 (**) was used to consider the significant differences from the control.

RESULTS

Sirtinol Affected Acanthamoeba Proliferation and Encystation

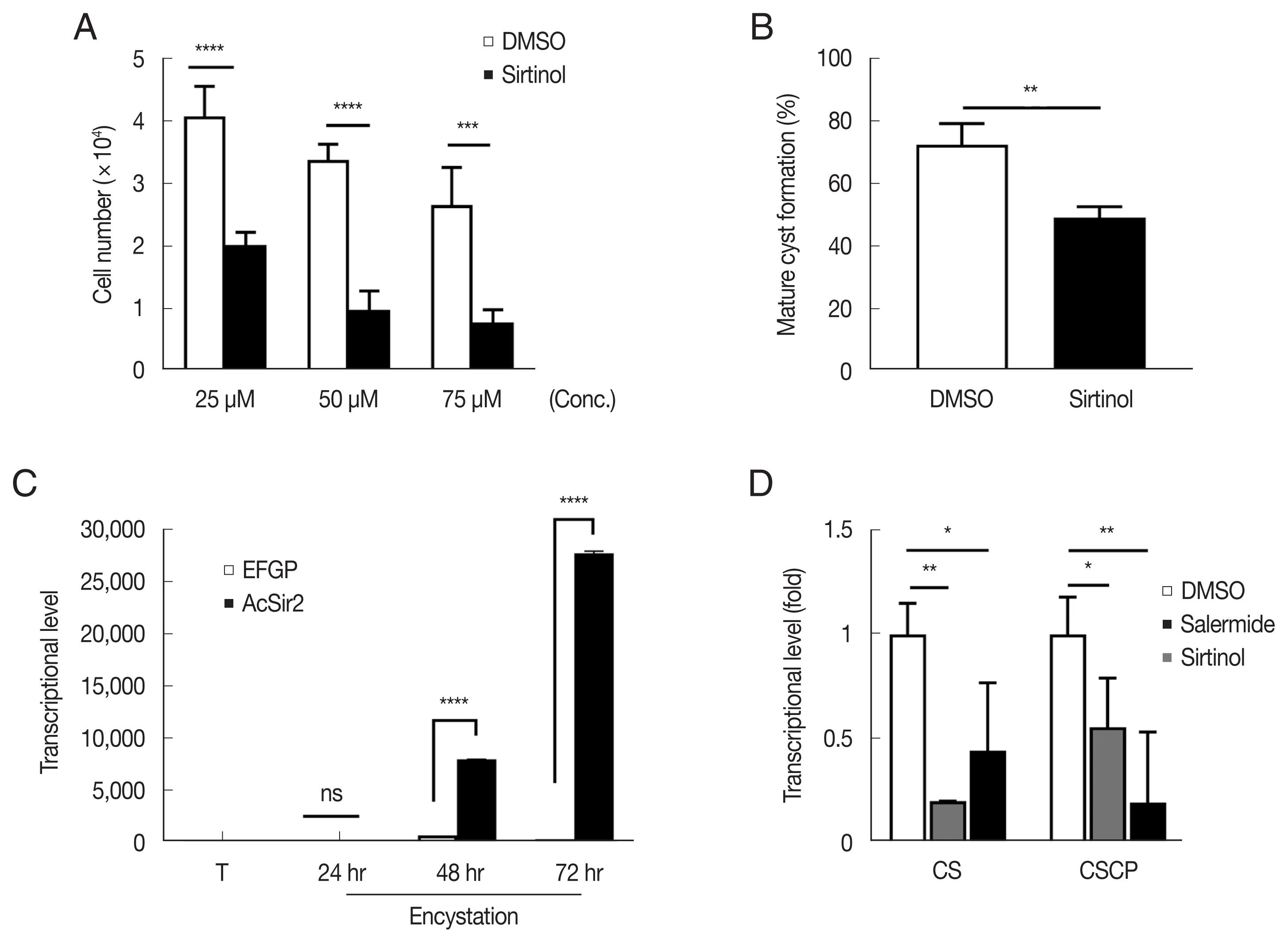

To determine the effect of sirtinol on Acanthamoeba proliferation, A. castellanii trophozoites were treated with sirtinol or DMSO (control) and incubated at 25°C for 48 hr. As shown in Fig. 1A, the number of sirtinol-treated cells significantly reduced by 49.6% (25 μM, P<0.0001), 29.2% (50 μM, P< 0.0001), and 28.7% (75 μM, P<0.001) after 48 hr, compared to those of DMSO-treated cells, respectively. This result indicated that sirtinol dose-dependently inhibited A. castellanii trophozoites proliferation.

Effects of sirtinol on the proliferation and encystation of A. castellanii trophozoites. (A) Trophozoites were incubated with various concentrations of sirtinol or DMSO (control). For each sirtinol or DMSO concentration, the data represent the mean cell number at 48 hr after incubation. (B) Effects of sirtinol on A. castellanii trophozoite encystation. A. castellanii trophozoites were transferred into an encystation medium containing 200-μM sirtinol and incubated for 24 hr. The mature cysts were counted under a microscope, followed by treatment with sarkosyl. DMSO was used as solvent control. (C) Transcriptional changes in CSCP in encysting AcSir2-overexpressing cells. AcSir2-overexpressing trophozoites (0 hr) and encysting cells at 24, 48, and 72 hr after encystation induction were examined for transcriptional changes in CSCP using qRT-PCR. CSCP transcriptional levels were normalized to that of Acanthamoeba actin. (D) Effects of sirtinol on transcription levels in CS and CSCP during the encystation process. Trophozoites were transferred into an encystation medium containing 100-μM sirtinol, incubated for 24 hr, examined for transcriptional changes in CS and CSCP using qRT-PCR, and compared to those of DMSO-treated cells. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001.

We then assessed whether sirtinol treatment inhibited the encysting process. For this, the encysting trophozoites were treated with sirtinol, and we assessed the encystation efficiency by counting the number of cysts under a light microscope. As shown in Fig. 1B, the encystation rate of cells treated with sirtinol significantly decreased to 39.8% (200 μM sirtinol) after 24 hr of incubation compared to controls (P<0.01), indicating that sirtinol suppressed Acanthamoeba encystation. From our previous results, Acanthamoeba CS transcription significantly increased in AcSir2-overexpressing cells and salermide treatment inhibited this CS upregulation. Thus, identifying the genes regulated by AcSir2 during encystation is crucial. As one of the gene screening processes, we used qRT-PCR to measure the transcriptional change of cyst-specific cysteine protease (CSCP), an Acanthamoeba cysteine protease involved in the degradation of unnecessary molecules and organelles during encystation [21], in AcSir2-overexpressing cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, CSCP transcription level in AcSir2-overexpressing cells was 11.6- and 88.6-fold higher at 48 and 72 hr after encystation induction, respectively, compared with vector control cells (P<0.0001). Thus, we initially examined the transcriptional levels of CS and CSCP in sirtinol-treated cells using qRT-PCR. The CS transcriptional levels in sirtinol-treated cells (100 μM) decreased but not significantly more than in salerimide-treated cells (100 μM) (P<0.1). However, those of CSCP in sirtinol-treated cells more significantly decreased to 20% (P<0.01) at 24 hr after encystation induction compared to those of control cells (Fig. 1D). These results were slightly different from our previous results in that salermide almost completely inhibited CS transcription. Sirtinol, in particular, suppresses CSCP transcription more significantly than salermide.

Morphological Changes in Encysting Cells Treated with Sirtinol

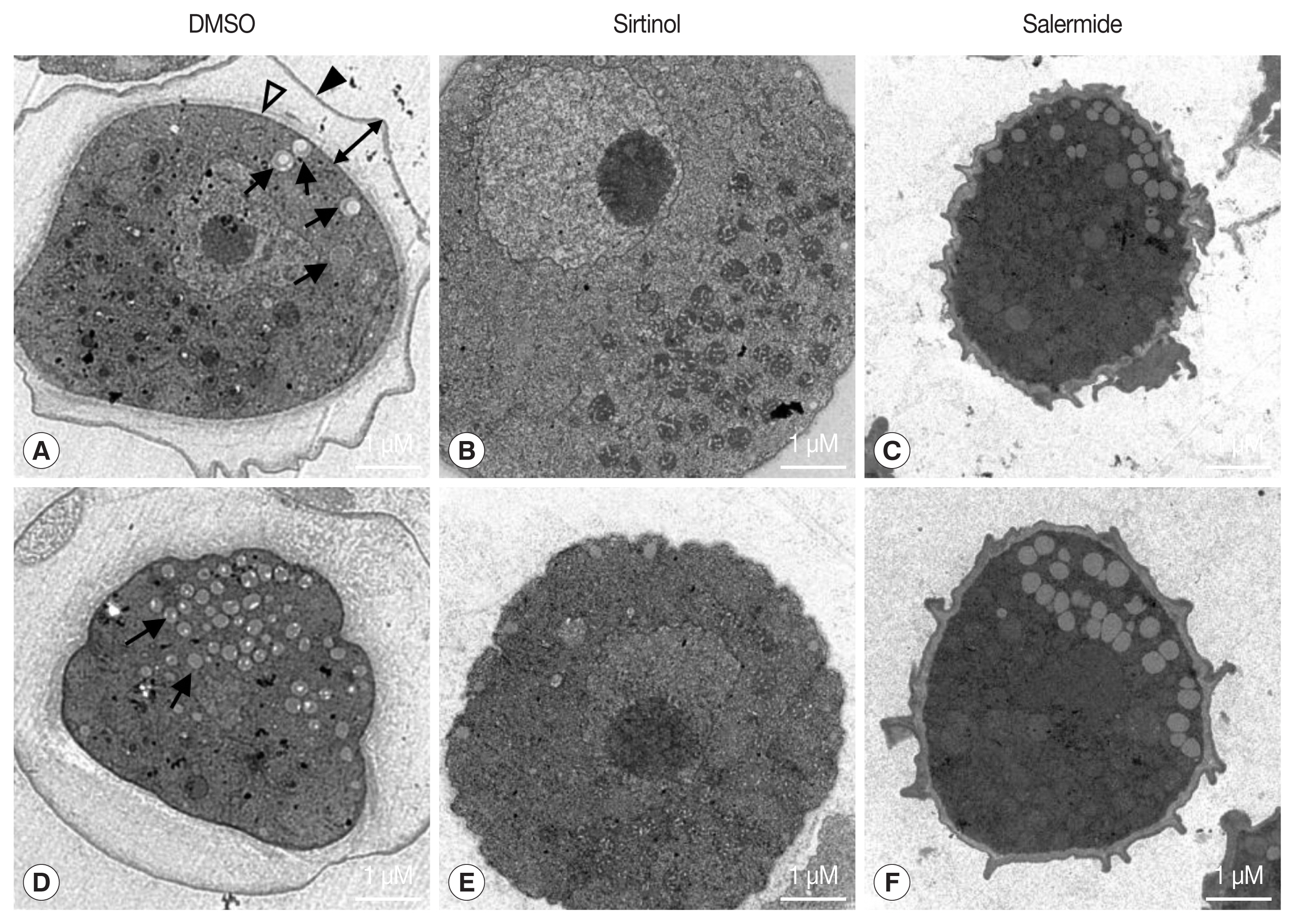

Next, we examined the ultrastructural changes in control (DMSO-treated cells) and encysting cells treated with sirtinol (100 μM) (Fig. 2) for 24 hr using TEM. After induction of encystation, control cells converted into mature cysts with double cyst walls, a laminar fibrous ectocyst (the outer cyst wall) (Fig. 2A, filled arrowheads), and an endocyst (the inner cyst wall) (Fig. 2A, open arrowheads) composed of fine fibrils in a granular matrix, as detected in Acanthamoeba cysts [5]. In the control cells, we detected the phagophore-like autophagic structures and observed partial degradation of organelles within the structures at 24 hr post-encystation induction (Fig. 2A, D, black arrows). When A. castellanii induced encystation by transferring into encystation medium containing 100 μM sirtinol for 24 hr, we hardly detected double cyst walls and autophagosome-like structures, and most organelles remained undigested (Fig. 2B, E), indicating that sirtinol delay or inhibit the autophagosome formation during encystation.

Inhibition of A. castellanii encystation using sirtinol treatment. Ultrastructural changes following treatment with sirtinol in the encysting of A. castellanii. Encystation was induced by transferring cells into an encystation medium containing DMSO (A, D), 100 μM sirtinol (B, E), or salermide (C, F) for 24 hr. The encystation medium also received the same amount of DMSO (as a solvent control). The black arrowhead, empty arrowhead, and black double-headed arrows, and black arrows indicate the exocyst wall, endocyst wall, intercyst space, and autophagosome-like structures, respectively. Scale-bar: 1 μM.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that the formation of cyst wall, particularly the endocyst wall, which is partially composed of cellulose [3,22,23], was significantly impaired due to transcription abolishment of CS [3,22,23]. However, the endocyst wall appears to be affected by the treatment of sirtinol, although its effect was not significant compared to cell treated with salermide. This study showed that the ectocyst wall disappeared compared with that of control (Fig. 2A, D) and salermide-treated cells (Fig. 2C, F). In addition, the number of autophagosome-like structures significantly reduced and undigested organelles, such as mitochondria remained in the cytoplasm of sirtinol-treated encysting cells. These results may be associated with CS transcriptional regulation in sirtinol-treated cells, which was not remarkably reduced compared to that of salermide-treated cells. These results suggest that endocyst wall was not significantly impaired in sirtinol-treated cells than in salermide-treated cells. CSCP transcription in sirtinol-treated cells decreased significantly than in salermide-treated cells, thereby resulting that the undegraded organelles and large molecules remained in sirtinol-treated cells during encystation (Fig. 1D).

Our study indicated that sirtinol and salermide could have different effects on encystation inhibition, which further implied that sirtinol is more effective in autophagy than salermide, and that salermide is more effective on cellulose synthesis for endocyst wall construction than sirtinol. Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved protein degradation pathway in eukaryotes, is essential during Acanthamoeba encystation by eliminating unwanted and/or unnecessary cell material, including mitochondria [24]. Although we did not observe evidence that AcSir2 is directly associated with autophagy in Acanthamoeba, recent studies in mammals revealed that Sirt1 deacetylase plays a critical role in autophagy regulation and provides a link between sirtuin function and the cellular response under limited nutrient conditions [25].

As is shown in Fig. 1A, sirtinol, like salermide, dose-dependently inhibited A. castellanii trophozoite growth. However, treatment with sirtinol (IC50=61.24 μM) inhibited Acanthamoeba proliferation more effectively than treatment with salermide (IC50=82.54 μM) [7]. To date, the active mechanism of sirtinol has not been elucidated; however, it exhibits various features that act in antidiabetic [26] and anticancer activities [27]. Sirtinol was known as a SIRT2 inhibitor prior to salermide [28]. Although salermide, a drug modified from sirtinol, has a greater inhibitory activity of SIRT1 and SIRT2 compared to sirtinol, several lines of evidence suggested that sirtinol is more effective against tumors in vitro [29]. Sirtinol inhibits SIRT2, which deacetylates phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PEPCK1) [26], resulting in a reduced level of PEPCK1 and decreased glucose production [30–32]. The PEPCK1, which plays a critical role in gluconeogenesis, is an enzyme involved in the defense of prolonged nutrient deprivation, such as fasting and starvation, in many multicellular mammalian cells. In the Acanthamoeba genome database (https://amoebadb.org/amoeba/app/), enzymes are related to the gluconeogenesis pathway, including the PEPCK homolog to allow prolonged survival of Acanthamoeba encysting cells, which may explain the inhibition of trophozoite proliferation by sirtinol treatment (Fig. 1A).

It is poorly understood how sirtinol and salermide act on Acanthamoeba sirtuin protein. However, our study demonstrated that both inhibitors sufficiently inhibited trophozoite proliferation and encystation. Our results indicated that the Acanthamoeba sirtuin proteins are valuable as prospective therapeutic targets for treating Acanthamoeba infections and the relevance of developing inhibitors that specifically act on Acanthamoeba sirtuin protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (NRF-2019R1I1A1A01061647).

Notes

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.