Determination of Knockdown Resistance (kdr) Allele Frequencies (T929I mutation) in Head Louse Populations from Mexico, Canada, and Peru

Article information

Abstract

The head louse Pediculus humanus capitis (De Geer) is a hematophagous ectoparasite that inhabits the human scalp. The infestations are asymptomatic; however, skin irritation from scratching occasionally may cause secondary bacterial infections. The present study determined the presence and frequency of the knockdown resistance (kdr) mutation T929I in 245 head lice collected from Mexico, Peru, and Canada. Head lice were collected manually using a comb in the private head lice control clinic. Allele mutation at T9291 was present in 100% of the total sampled populations (245 lice) examined. In addition, 4.89% of the lice were homozygous susceptible, whereas 6.93% heterozygous and 88.16% homozygous were resistant, respectively. This represents the second report in Mexico and Quebec and fist in Lima.

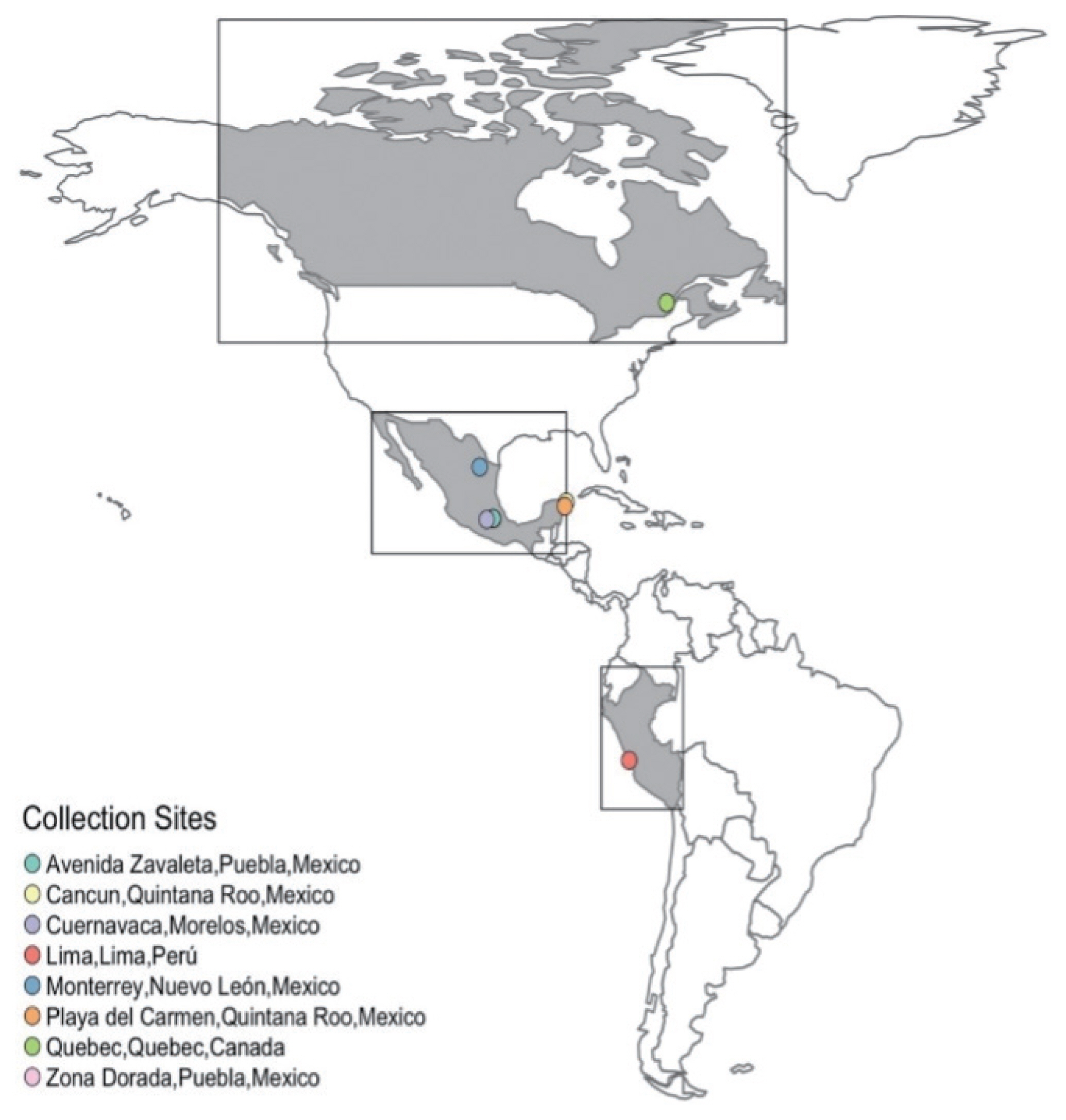

Pediculosis is a public health problem affecting the health of children aged 3 to 12 years, regardless of economic status [1–4]. Pediculus humanus capitis is a vector of Bartonella quintana and seems to be a potential transmitter of Rickettsia prowazekii [5]. Pyrethroid insecticides are potent neurotoxicants affecting voltage-sensitive sodium channels (VSSCs). The VSSCs are integral membrane proteins responsible for the conduction of sodium ions that open or close the channels. Over the last 2 decades, many cases of resistance to pyrethrin- and pyrethroid-based pediculicides have been documented [6,7]. Knockdown resistance (kdr) is a major attribute of resistant lice and supports the claim that treatment failures are largely due to insecticide resistance [7]. Molecular markers have been used to detect the presence of kdr mutations in sodium channel genes [3,6–10], which are associated with pyrethroid resistance genes. Detection of the early phase of resistance is crucial to efficient long-term management, which can delay and/or reverse the development of resistance [11]. All head lice samples were collected manually using a comb (fine-toothed comb Beka No 136, México. D.F.) All samples were collected in the head lice control clinic (ItchyBitsi SPA), in Quebec (Canada), Lima (Peru), and 5 places México (Monterrey, Cancun, Playa del Carmen, Puebla (Zona Dorada and Zavaleta), Cuernavaca) (Fig. 1) with ethics statement (N°01/ORD/2015). The collected specimens were immediately stored in absolute ethanol (99.8%). Genomic DNA was extracted from each individual specimen using a salt extraction technique [12]. Concentration and quality of each DNA sample were determined with a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the polymorphic region of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel α-subunit gene was performed in a total reaction volume of 25 μl. The reaction mix contained ~200 ng of genomic DNA, 0.1 μM of each primer, 2.5 μl of 10× Taq polymerase buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mM MgCl2), 0.2 mM dNTPs and 0.15 U Taq DNA polymerase (Bioline, Taunton, Massachusetts, USA). The primer sequences for the α-subunit genes were forward 5′-AAATCGTGGCCAACGTTAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-TGAATCCATTCACCGCATAA-3′ [3]. The reaction mix was incubated for 5 min at 94°C for the initial denaturation, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step of 72°C for 3 min. A 20-μl aliquot of the PCR product was mixed with 2 U SspI (Invitrogen, San Diego, California, USA), restricted with enzyme, and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The polymorphisms were categorized as follows: susceptible “SS” homozygote (non-cleavable), visualized as a 332-bp band; resistant “RR” homozygote (cleavable), visible as 2 bands (261 and 71 bp); or “RS” heterozygote, visible as 3 bands (332, 261, and 71 bp). The digestion product was loaded on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide for UV light visualization (Fig. 1). To confirm the genotype, samples were sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator v3.1. Cycle Sequencing Kit and the same PCR primers used for amplification. The reactions were analyzed in the ABI PRISM 3,100 Genetic Analyzer using the Sequencing Analysis Software v5.3 (Applied Biosystems) and Gene Studio ver2.2.0.0 molecular biology suite. Genotypic frequencies (f) were calculated by dividing the number of lice with a specific genotype by the total number of lice analyzed. Genotype frequencies at the 929 locus were tested to fit the Hardy-Weinberg assumptions using a χ2 goodness-of-fit test with one degree of freedom [13]. Wright’s inbreeding coefficient (FIS) was calculated using the formula: FIS=1−(Hobs/Hexp), where Hobs is the number of heterozygotes observed and Hexp the expected genotypes. The 95% confidence interval was calculated using the Wald test:

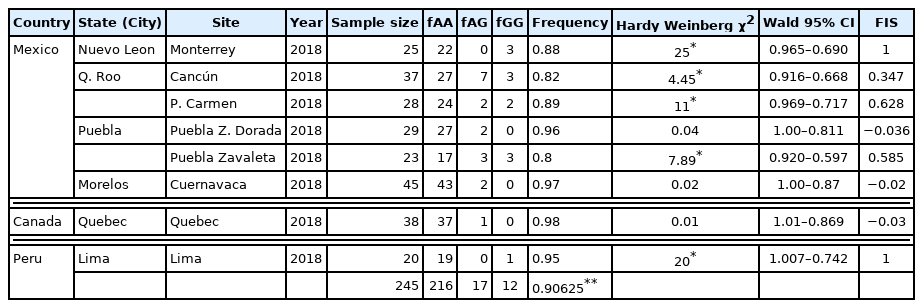

Table 1 shows the location, collection years, sample size, number of individuals with each genotype, and the frequency of kdr T929I in each collection and confidence interval. If FIS was significantly ≥0, then an excess of homozygotes was present, whereas, if FIS was significantly <0, an excess of heterozygotes was present. Eight collections using the Hardy-Weinberg model. We analyzed genotype frequencies were not in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in 3 of the 8 populations (Table 1): Puebla (zona dorada), Cuernavaca and Quebec. In all populations, FIS was higher than 0, indicating an excess of homozygotes (Table 1). The mutant genotype (RR) was identified by 2 bands (261 and 71 bp). The heterozygote (RS) showed 3 bands (332, 261, and 71 bp), and the normal genotype (SS) was identified by a single band (332 bp). While the presence of kdr-type mutations alone may not directly predict clinical failure, their increasing frequency in louse populations coincides with reports of product failures in controlled studies [15]. One of the factors contributing to increasing numbers of head lice infestations is insecticide resistance. Therefore, molecular markers, such as kdr-like polymorphisms, may be useful because they allow the processing of large numbers of insects from many populations relatively quickly.

Results of kdr T929I mutation in head lice P. h. capitis samples collected from Mexico, Canada, and Peru

We examined 245 head lice samples and found that 95.1% of those lice carried the resistance allele. This percentage is similar than that obtained by Bialek et al. [10], who examined 120 head lice samples and found the kdr-like (Thr929Ile and Leu932Phe) gene in 112 lice (93%), with the remaining 8 carrying the wild-type gene. These similarities may be due to the fact that selection pressure is being exerted with the same active ingredient. Subsequent studies in Mexico, Ponce et al. [16], determined frequencies of the T929I mutation, between 0.32–0.96 for the state of Nuevo León and between 0.35–0.82 for the state of Yucatan. These high frequencies agreed with results obtained with the current investigation, however, the minimum frequency obtained of 0.80, indicates that in other states of Mexico the use of formulated products based on permethrin is evident. Marcoux et al. [6] collected lice in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, and analyzed the specimens by using serial invasive signal amplification reaction to genotype the T917I mutation. They reported that 133/137 (97.1%) head lice samples had a resistant genotype, and 2.9% had a susceptible genotype. Currently these frequencies are maintained in Quebec, as our results showed a 98% resistant genotype. With respect to Lima (Peru), there are no reports of mutations associated with voltage-dependent sodium channels. In Japan, 4 mutations (D11E, M815I, T929I, and L932F) in the sodium channel gene of human head lice samples were reported [9]. Out of 630 head lice examined 55 (8.7%) possessed homozygous and heterozygous kdr-like genes, in which the 4 mutations existed concomitantly. Likewise, Clark [11] determined the kdr allele frequency of head lice populations collected from different countries. In the populations collected in the United States, the overall resistance allele frequency was 75.1%. In South America, the same author found resistance allele frequencies of 89.5% for Argentina, 62.5% for Brazil, 0% for Ecuador, and 100% for Uruguay. The same study showed resistance allele frequencies of 83% for populations in Denmark and 27.5% for the Czech Republic. Durand et al. [1] in Bobigny, France, determined 22.2% of homozygous were susceptible at position 929 of the kdr-like allele, 36.7% were homozygous resistant, and 41.1% were heterozygous. Thus, 77.8% of the lice studied carried 1 or 2 T929I mutant alleles [1]. Globally, the frequency of the T929I mutation was 0.57. Kristensen [17] evaluated the presence of the T929I haplotypes in head lice collected from several schools in Denmark. Kristensen determined that 57.9% of the samples analyzed were homozygous resistant, 15.8% were heterozygous, and 26.3% were homozygous susceptible. These results differ from our present results when the presence of the kdr mutation (T929I) predominates, with 4.9% homozygous susceptible, 17.0% heterozygous, and 88.2% homozygous resistant. The results of Durand et al. [1] coincide with the allele frequency results obtained by Clark [11] and Hodgdon et al. [7], who determined the kdr allele frequencies (T917I mutation) of head lice from 14 countries using the serial invasive signal amplification reaction. Lice collected from Uruguay, the United Kingdom, and Australia had kdr allele frequencies of 100%, whereas lice from Ecuador, Papua New Guinea, South Korea, and Thailand were missing the kdr allele. In the remaining 7 countries investigated, 7 populations from the United States, 2 from Argentina, and 1 each from Brazil, Denmark, Czech Republic, Egypt, and Israel displayed variable kdr allele frequencies, ranging from 11 to 97%. Meanwhile, Brownell et al. [18], analyzed 260 head lice samples collected from 15 provinces in the 6 regions of Thailand, to identify the kdr T917I mutation. Of these 156 (60. 00%) were SS, 58 (22.31%) were RS, and 46 (17.69%) were RR. The overall frequency of the kdr T917I mutation was 0.31. Kelsey et al. [19] also detected the T917I kdr amino acid substitution in 2 head lice populations; frequencies ranging between 0.45–0.5. The total frequency of this substitution was 0.47. Of these, 5 (6.1%) were homozygous susceptible and 78 (93.9%) were heterozygotes, while the kdr-resistant homozygote (RR) was not detected. Thus, 93.9% of the head lice collected in Honduras harbored only 1 T917I allele. Our study revealed the presence of the kdr mutation T929I in all head lice populations collected. These results provide evidence that head lice populations are developing resistance to pyrethroids. Although there is evidence that kdr mutations have generated resistance to pyrethroid insecticides [1,20–23], there are no related insecticide susceptibility results in Canada, Mexico, and Peru. This should be determined in the future investigations and correlations be made with the frequency of kdr mutation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lizeth Rocha for her collaboration in this research work. We especially thank the principals, parents and children for their cooperation.

Notes

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.