Mapping of the Complement C9 Binding Region on Clonorchis sinensis Paramyosin

Article information

Abstract

Heliminthic paramyosin is a multifunctional protein that not only acts as a structural protein in muscle layers but as an immune-modulatory molecule interacting with the host immune system. Previously, we found that paramyosin from Clonorchis sinensis (CsPmy) is bound to human complement C9 protein (C9). To analyze the C9 binding region on CsPmy, overlapping recombinant fragments of CsPmy were produced and their binding activity to human C9 was investigated. The fragmental expression of CsPmy and C9 binding assays revealed that the C9 binding region was located at the C-terminus of CsPmy. Further analysis of the C-terminus of CsPmy to narrow the C9 binding region on CsPmy indicated that the region flanking 731Leu–780Leu was a potent C9 binding region. The CsPmy fragments corresponding to the region effectively inhibited human C9 polymerization. These results provide a precise molecular basis for CsPmy as a potent immunomodulator to evade host immune defenses by inhibiting complement attack.

INTRODUCTION

Clonorchis sinensis, the oriental liver fluke, is one of the important foodborne trematode parasites causing chronic hepatobiliary disease in China, Korea, northern Vietnam, and eastern Russia [1,2]. The zoonotic parasite usually infects humans who consume raw or undercooked freshwater fish contaminated with the metacercariae. The metacercariae excyst in the duodenum, move to the bile ducts, and induce several pathological alterations in the bile ducts via prolonged mechanical and biochemical stimulations. Chronic and heavy infection usually causes hepatobiliary diseases such as cholangitis, cholelithiasis, and cholangiectasis, and can cause cholangiocarcinoma [2,3].

Paramyosin is an α-helical rod-shaped myofibrillar protein exclusively found in invertebrates [4,5]. Paramyosin has also been identified in helminth parasites including Schistosoma mansoni, Fasciola hepatica, Paragonimus westermani, Clonorchis sinensis, Brugia malayi, Echinococcus granulosus, Taenia saginata, and Trichinella spiralis [6–13]. Paramyosin in helminth parasites is likely to play multiple roles. The primary function of the protein in helminth parasites is a structural role mediating muscle contraction, but it also acts as a host immune-modulating molecule by repressing the classical complement cascade pathway [14–16] and acting as an Fc receptor [17,18].

Previously, we identified and characterized a paramyosin from C. sinensis (CsPmy). CsPmy is distributed in the subtegumental muscle, tegument. The protein was the muscle layer surrounding the intestine of the parasite. The protein was constitutively expressed in various developmental stages of the parasite, suggesting its essential role in muscular contraction activity [13]. The high immunogenic properties of CsPmy suggest its potential as a reliable serodiagnostic antigen for clonorchiasis [13,19]. The binding ability of CsPmy to human complement C9 (C9) also suggests its plausible role in immunological defenses by repressing the host immune response [13]. In the present study, we investigated the inhibitory function of CsPmy on C9 polymerization and mapped the C9 binding region on CsPmy to provide an in-depth molecular basis for CsPmy as a potential immunomodulator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mapping of the C9 binding region of CsPmy

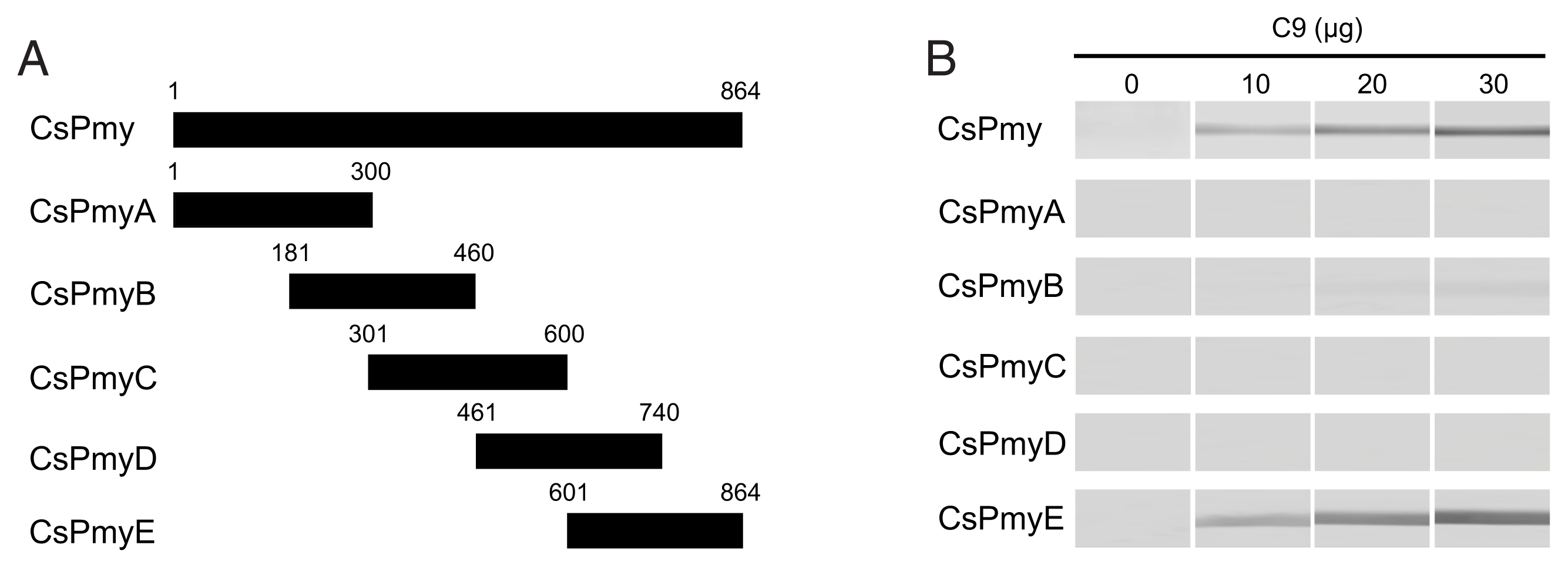

To identify the C9 binding region on CsPmy, full-length CsPmy was fragmented into 5 overlapping fragments of CsPmyA (1Met–300Glu), CsPmyB (181Leu–460His), CsPmyC (301Tyr–600Glu), CsPmyD (461Asp–740Ala), and CsPmyE (601Val–864Met) (Fig. 1A). The CsPmy expression clones used in this study were constructed in our previous study [13,19]. Each expression construct was expressed in Escherichia coli and recombinant CsPmy fragment was purified as described previously [19]. To determine the C9 binding region on the recombinant CsPmy fragments, the 5 recombinant proteins (2 μg) were subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). The membrane was cut into strips and blocked with 5% skim milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) at room temperature (RT) for 2 h. The strips were separately incubated with different amounts of recombinant human C9 (10, 20, or 30 μg/ml; Quidel, San Diego, California, USA) in PBS at 37°C for 2 h [16]. After washing with PBST several times, the strips were probed with goat anti-human C9 antibody (1:500 dilution; Quidel) at RT for 2 h. The membrane was reacted with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-goat IgG (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) at RT for 2 h. The strips were washed with PBST several times and the immunoreactive bands were visualized using 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma).

Determination of the C9 binding region on CsPmy. (A) Scheme for expression constructs. To identify the C9 binding region on CsPmy, the gene was fragmented into 5 overlapping fragments (CsPmyA-CsPmyE). (B) Immunoblot analysis. To determine the C9-binding region on CsPmy, full-length recombinant CsPmy and 5 fragmented recombinant proteins (CsPmyA-CsPmyE) were expressed in E. coli and purified [13,19]. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted. Each membrane was cut into strips, incubated with different concentrations (0, 10, 20, and 30 μg) of human C9 at RT for 2 h, and reacted with goat anti-human C9 antibody followed by HRP-conjugated mouse anti-goat IgG.

Fine mapping of the C9 binding region on CsPmyE

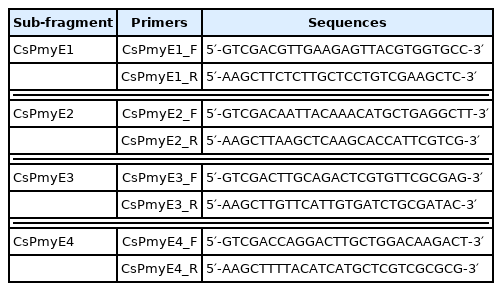

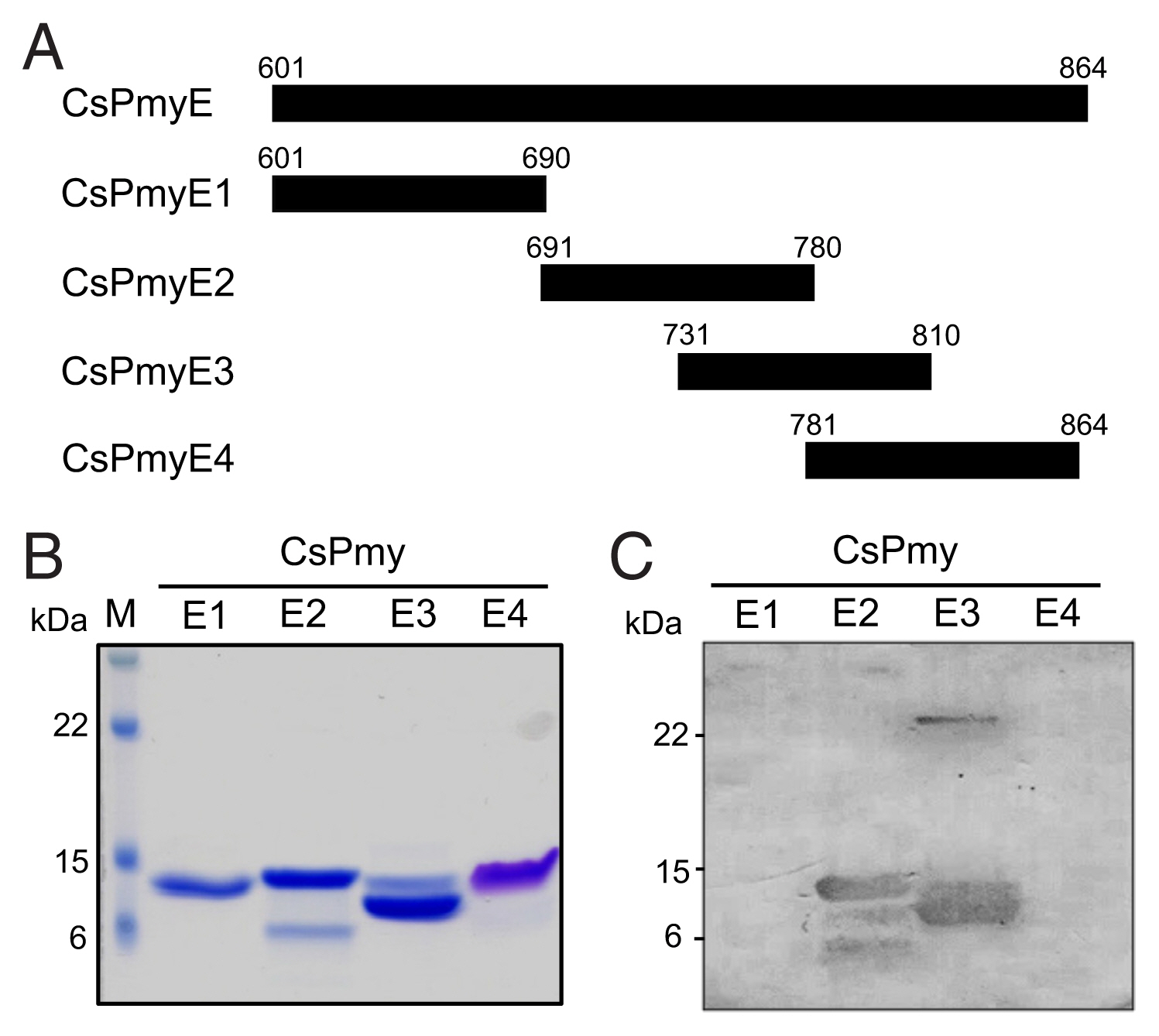

To further narrow the C9 binding region on CsPmy, CsPmyE was fragmented into 4 separate sub-fragments: CsPmyE1 (601Val–690Glu), CsPmyE2 (691Asn–780Leu), CsPmyE3 (731Leu–810Asn), and CsPmyE4 (781Gln–864Met) (Fig. 2A). Each sub-fragment was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primer pairs for each sub-fragment (Table 1). The amplification profile was 94°C for 5 min and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a 72°C extension for 5 min. Each amplified PCR product was purified from the gel, cloned into a T&A cloning vector (Real Biotech Corporation, Banqiao City, Taiwan), and transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells. The nucleotide sequence of each cloned CsPmyE sub-fragment was confirmed by automatic DNA sequencing. Each fragmented CsPmyE was cloned into the bacterial expression vector pQE-9 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and transformed into E. coli M15 [pREP4] cells (Qiagen). The expression of the recombinant proteins was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG; final concentration 1 mM) at 37°C for 3 h with gentle shaking at 200 rpm for aeration. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and the bacterial cells were suspended in native lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), sonicated on ice, and centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min at 12,000×g. The supernatants were collected and recombinant CsPmyE sub-fragments were purified via nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) chromatography (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The purification and purity of the recombinant sub-fragments were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE. To determine the binding ability of the recombinant CsPmyE fragments to C9, the recombinant proteins (2 μg) were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE, then immunoblotted as described above.

Fine mapping of the C9 binding region in CsPmy. (A) Scheme of the expression construct design. To identify the C9 binding region in CsPmyE, the gene was fragmented into 4 separated sub-fragments (CsPmyE1-CsPmyE4). (B) SDS-PAGE. The recombinant CsPmyE sub-fragments were expressed in E. coli, purified with Ni-NTA affinity column, and analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE. Lane M, size marker proteins; lane E1, CsPmyE1; lane E2, CsPmyE2; lane E3, CsPmyE3; lane E4, CsPmyE4. (C) Immunoblot analysis. Each recombinant protein was separated on 15% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted. The membrane was incubated with human C9 (30 μg) for 2 h and reacted with goat anti-human C9 antibody followed by HRP-conjugated mouse anti-goat IgG. Lane E1, CsPmyE1; lane E2, CsPmyE2; lane E3, CsPmyE3; lane E4, CsPmyE4.

C9 polymerization inhibition assay

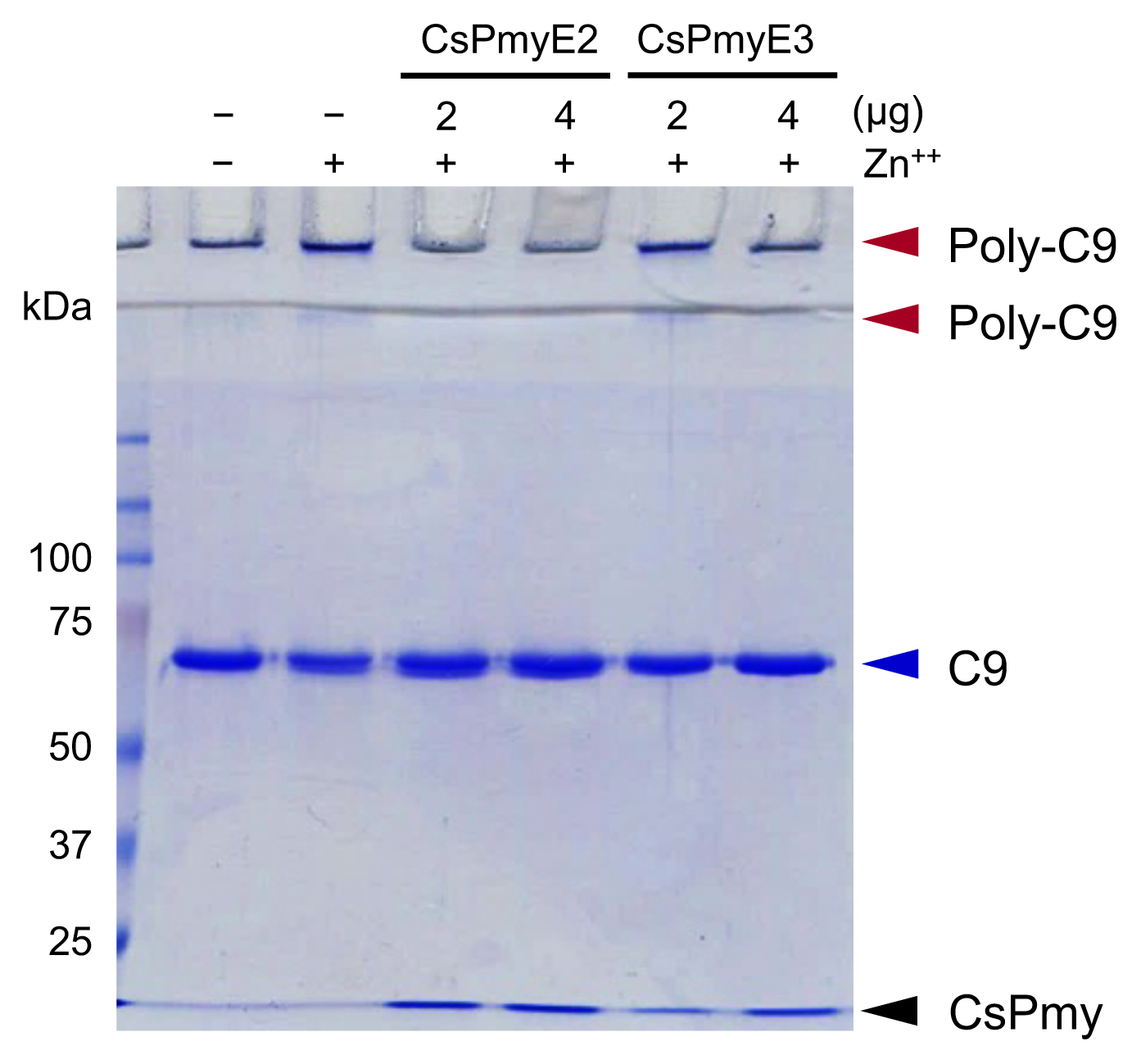

To analyze the inhibitory effect of CsPmyE fragments on C9 polymerization, recombinant CsPmyE2 (2 or 4 μg) or CsPmyE3 (2 or 4 μg) was pre-incubated with human C9 (2 μg; Quidel) in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2) supplemented with 50 μM ZnCl2 at 37°C for 2 h [20]. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE to detect the inhibitory effect of CsPmyE fragments on Zn2+-induced C9 polymerization [21].

RESULTS

Mapping of the C9 binding region on CsPmy

To identify the C9 binding region on CsPmy, full-length CsPmy was fragmented into 5 overlapping fragments, CsPmyA, CsPmyB, CsPmyC, CsPmyD, and CsPmyE (Fig. 1A). The immunoblot analysis of the 5 recombinant CsPmy fragments (CsPmyA-CsPmyE) revealed that human C9 bound to CsPmyE specifically in a dose-dependent manner, albeit weak reactivity for CsPmyB was also detected (Fig. 1B). To further narrow the C9 binding region on CsPmy, CsPmyE was fragmented into 4 separate sub-fragments and expressed in E. coli. All recombinant proteins (CsPmyE1-CsPmyE4) were expressed with the predicted molecular sizes (Fig. 2B). Immunoblot analysis of the 4 CsPmyE sub-fragments revealed that human C9 bound to CsPmyE2 (691Asn–780Leu) and CsPmyE3 (731Leu–810Asn), but stronger reactivity was detected for CsPmyE2 (Fig. 2C).

Inhibition of C9 polymerization by CsPmy

The inhibitory function of CsPmyE fragments on C9 polymerization was analyzed. Polymerized C9 precipitates induced by Zn2+ were observed in the wells and the border area between the separating gel and the stacking gel on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). Both CsPmyE2 and CsPmyE3 inhibited C9 polymerization in dose-dependent manners, resulting in disappearances of the precipitates on the gel. CsPmyE2 showed a stronger inhibitory effect on C9 polymerization than CsPmyE3.

Inhibition of C9 polymerization by CsPmyE sub-fragments. Human C9 (2 μg) was incubated with different amounts (2 or 4 μg) of recombinant CsPmyE2 or CsPmyE3 in the presence of 50 μM ZnCl2 at 37°C for 2 h. The samples were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Polymerized C9 (Poly-C9) precipitates (red arrows) were detected in the wells and the border area between the separating gel and the stacking gel. Blue arrow, not polymerized human C9; black arrow, CsPmyE.

DISCUSSION

The complement cascade is a key component of the innate immune defense system against pathogens including parasites and provides the first line of defense by promoting the recruitment of leukocytes to infected foci and modulating the function of cytotoxic effector leukocytes [22,23]. To evade the host immune attack mediated by the complement system, parasites have developed sophisticated complement evasion strategies, which include the recruitment of host complement regulatory components and the presentation of molecules inactivating complement cascade on their surfaces [24–26]. Therefore, parasite-encoded proteins involved in the regulation of the host complement system have been attractive targets for the development of drugs and vaccines. Diverse complement evasion molecules have been identified in helminth parasites, among which paramyosin is one of the most extensively studied molecules [6–17]. CsPmy is a protein found in the tegumental layer of C. sinensis and shares similar structural properties with paramyosin from other helminth parasites such as S. mansoni, P. westermani, and T. spiralis [13]. The fine mapping of the C9 binding region on CsPmy demonstrated that the potential C9 binding site was located on the C-terminal part of CsPmy and further identified the region between CsPmyE2 (691Asp–780Leu) and CsPmyE3 (731Leu–810Asn), which overlapped with 731Leu–780Leu. This is consistent with previous reports that the C9 binding site was located at the C-terminal parts of paramyosin from S. mansoni (SmPmy) [27] and paramyosin of T. spiralis (TsPmy) [28]. Especially, the C9 binding region of CsPmy is well matched to that of SmPmy (744Asp–866Met) [27]. However, the C9 binding site of TsPmy was found at the extreme end of the C-terminal, 866Val–879Met [28]. The effective inhibition of C9 polymerization by the CsPmyE fragment suggests that the CsPmy region may be a key structural element to modulate host immune responses by inhibiting the formation of the membrane attack complex and thereby, contributing to parasite evasion of the activated host complement attack. Further structure-based functional analysis of helminth paramyosin may be necessary for an in-depth understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms of the protein in helminth parasites involved in host immune escape.

In conclusion, we mapped the complement regulatory region on CsPmy, which bound to human C9 and inhibited its polymerization. Our results suggest the precise molecular basis for CsPmy as a potent immunomodulator, which may contribute to the evasion of the host complement system by C. sinensis. Determination of the complement-binding region on CsPmy may also provide a feasible approach to designing epitope-based subunit vaccines for clonorchiasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (NRF-2016R1C1B1009348).

Notes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.