Molecular and biochemical characterization of hemoglobinase, a cysteine proteinase, in Paragonimus westermani

Article information

Abstract

The mammalian trematode Paragonimus westermani is a typical digenetic parasite, which can cause paragonimiasis in humans. Host tissues and blood cells are important sources of nutrients for development, growth and reproduction of P. westermani. In this study, a cDNA clone encoding a 47 kDa hemoglobinase of P. westermani was characterized by sequencing analysis, and its localization was investigated immunohistochemically. The phylogenetic tree prepared based on the hemoglobinase gene showed high homology with hemoglobinases of Fasciola hepatica and Schistosoma spp. Moreover, recombinant P. westermani hemoglobinase degradaded human hemoglobin at acidic pH (from 3.0 to 5.5) and its activity was almost completely inhibited by E-64, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor. Immunohistochemical studies showed that P. westermani hemoglobinase was localized in the epithelium of the adult worm intestine implying that the protein has a specific function. These observations suggest that hemoglobinase may act as a digestive enzyme for acquisition of nutrients from host hemoglobin. Further investigations may provide insights into hemoglobin catabolism in P. westermani.

INTRODUCTION

Paragonimus westermani is a typical digenetic medically important parasite, which causes paragonimiasis in humans and animals, i.e., tigers, dogs, cattle, pigs, cats, and feral carnivores (Shim et al., 1991; Toscano et al., 1995). P. westermani has been reported in Asia, Africa, and Americas (Piekarski, 1989). Although the total number of persons infected worldwide has not been determined, annually about 200 and 500 cases are sporadically reported in Japan and Korea, respectively. Human infections are closely related with eating habits, and in many endemic regions, people become infected by eating raw or undercooked freshwater crustaceans.

The proteinases of a number of parasites have been investigated to elucidate their roles in parasite infection, survival and pathogenicity (McKerrow, 1989; Auriault et al., 1982; Carmona et al., 1993; Tamashiro et al., 1987; Sakanari et al., 1989). The primary function of the secreted proteolytic enzymes of parasites is the digestion of host tissue components such as collagens and hemoglobin to facilitate parasite invasion and enable it to obtain nutrients (Brady et al., 1999; Goldberg et al., 1990; Rosenthal et al., 1988), and host hemoglobin may be an important source of nutrients for Paragonimus.

Blood consuming parasites depend on hemoglobin catabolism for survival, and several putative hemoglobin degrading enzymes have been already characterized in protozoans and helminths,: including Plasmodium falciparum (Dahl et al., 2005), Plasmodium sp. (Berry et al., 1999; Moon et al., 1997; Silva et al., 1996), Ancylostoma caninum (Harrop et al., 1996), Strongyloides stercoralis (Gallego et al., 1998), Haemonchus contortus (Longbottom et al., 1997), Caenorhabditis elegans (Ray et al., 1992), Haplometra cylindracea (Hawthorne et al., 1994) and Schistosoma mansoni (Silva et al., 2002; Baig et al., 2002). In addition, these proteolytic enzymes have been shown to belong to either cysteinyl or aspartyl families of peptidases (Dalton et al., 1995).

Maturing and adult schistosomes live in blood vessels of human hosts, where they feed on red blood cells. S. mansoni uses a variety of proteinases, referred to as hemoglobinases, to obtain nutrients from host globin (El Meanawy et al., 1990). These hemoglobinases offer a means of understanding parasitism by P. westermani, however, hemoglobin-hydrolyzing activities of this parasite have not been characterized. Thus, we considered that elucidation of the hydrolysis of host hemoglobin by P. westermani hemoglobinase could add to our understanding of feeding mechanisms employed by these organisms.

In this study, a cDNA clone encoding a 47 kDa hemoglobinase of P. westermani was isolated and characterized. The antigenicity of the recombinant protein and its localization in the adult worm were investigated to evaluate the biologic function of this hemoglobinase in P. westermani.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of parasites

Metacercariae of Paragonimus westermani were recovered from naturally infected crayfish collected from Youngam, for triploid P. westermani, an indigenous area, Jeollanam-do, Korea (Park GM et al., 2001). Collected crayfish were digested with artificial digestive juice by incubation for 2 h at 37℃. Metacercariae were collected under a dissecting microscope and washed 3 times with autoclaved saline. Fifty metacercariae were fed to 4 experimental dogs, and 16 weeks later, the dogs were sacrificed to obtain adult worms. Lung lobes were carefully examined for the presence of worm cysts, and adult worms collected from cysts were washed 3 times with autoclaved saline, and incubated for 30 min to excrete host tissues.

Gene cloning and sequence analysis

The cDNA used in this study was derived from EST analysis of P. westermani adults in our laboratory (Kim et al, 2006). Based on a partial hemoglobinase from EST analysis, we designed primer for RACE PCR to obtain the full sequence. The primers were as follows: Forward 5'-actgtttaccgtggcttctctca-3'. RACE-PCR was performed using gene-specific primers over 30 cycles of 94℃ for 30 sec, 68℃ for 30 sec and 72℃ for 3 min. RACE-PCR product was analyzed on 1% agarose gels, extracted and cloned into pGEM T-Easy vectors (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) for sequence confirmation.

Sequences obtained were searched for homology using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool X (BLASTx) program designed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), National Institutes of Health (USA). Sequences with other previously reported hemoglobinase in the database were searched for using the ClustalW version 1.82 available from the European Bioinformatics Institute Server, predicted motifs and secondary structures were obtained using PredictProtein, a sequence analysis and protein structure prediction service operated by the University of Columbia Bioinformatics Center.

The full sequence of the hemoglobinase gene was obtained by PCR using template cDNA constructed according to manuals (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA). PCR was performed using gene-specific primers over 30 cycles of 94℃ for 30 sec, 68℃ for 3 min, and 72℃ for 3 min, using Taq-polymerase (Intron Biotechnology Inc, Sungnam, South Korea). The PCR product obtained was checked by electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel, extracted, and cloned into pGEM T-Easy vectors (Promega) for sequence confirmation. The sequences of the primers were as follows: forward 5'-ccggaattcatgccgggagttccagc-3' and reverse 5'-ccgctcgagttatgatgcacacacgttc-3'.

Expression and purification of recombinant hemoglobinase

To produce recombinant hemoglobinase, the above PCR product and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) Gene Fusion System was utilized (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Briefly, the full length PCR product cloned into pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega) was cleaved with EcoR I and Xho I, and ligated into equivalently cleaved pGEX-4T1 expression vectors (Amersham Biosciences). After ligation, the constructed vectors were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 using standard methods (Sambrook et al., 1989), and transformants were selected using ampicillin. An E. coli strain BL21 was verified by digesting plasmid with corresponding restriction enzymes, electrophoresing in 1% agarose gel and by sequencing the plasmid.

To determine optimum conditions for expressing hemoglobinase, different growth conditions, i.e., a temperature and isopropyl β-D thiogalactoside (IPTG) concentration, were examined. To induce pGEX-4T1/hemoglobinase, we used IPTG at 4 different concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 0.5 and 1.0 mM), and 5 different growth temperatures (20℃, 25℃, 30℃, 35℃, and 37℃).

Bulk cultures were lysed by sonication. Proteins expressed were bacterial lysate inclusion bodies. To purify recombinant hemoglobinase, inclusion bodies were dissolved in IB buffer (1 ml PBS, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% N-lauroyl sarcosine (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and sonicated, and GST was excised from fusion protein by thrombin cleavage. Recombinant hemoglobinase was purified by gel elution using an electroeluter (BioRad, Hercules, California, USA) and then dialyzed twice versus 0.1 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Additional dialysis was performed in 0.1 mM Tris-HCl without 0.1% Triton X-100. Protein purity was checked by SDS-PAGE and concentrations were determined by using Lowry assays using bovine serum albumin (BioRad) as a standard.

Hemoglobin hydrolysis assay

The hydrolysis of hemoglobin by cysteine proteinase in other organisms, i.e., P. falciparum and S. mansoni, was studied. To evaluate the hydrolysis of hemoglobin (Sigma), hemoglobin was incubated at 37℃ with purified recombinant hemoglobinase in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer at different pH (from 3.0 to 6.0 with intervals of 0.5). After incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Product was electrophoresed in 15% polyacrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie blue. The inhibition of hemoglobinase by E-64 (a cystein proteinase inhibitor) was also studied. To evaluate hemoglobinase inhibition by E-64, hemoglobin was incubated at 37℃ with purified recombinant hemoglobinase in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 3.5. Products were then electrophoresed in 15% polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue.

Production of antibodies against recombinant hemoglobinase

Purified recombinant hemoglobinase (> 100 μg) was subcutaneously injected into two 6-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Bionics, Seoul, South Korea) with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma). Prior to immunization, negative blood samples were collected from the rats for control experiments. Two boosters of hemoglobinase were administered at 14 and 28 days after the first injection using recombinant hemoglobinase (> 100 μg) in equal volumes of Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma). Blood samples were collected from rats before administering boosters to monitor antibody production. Antiserum was obtained from the heart 14 days after the final booster. Anti-recombinant hemoglobinase antibodies were obtained from blood by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 min at 4℃ and analyzed by western blotting.

Western blotting

Recombinant hemoglobinase was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), which were then blocked overnight in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at 4℃, washed with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST), incubated with 1:1,000 diluted recombinant hemoglobinase antiserum, washed with TBST and incubated with 1:2,000 diluted rat immunoglobulins/horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled antibodies (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). For detection, ECL Western blotting detection reagents were used (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunohistochemical staining

Hemoglobinase was localized in worms by immunostaining. Briefly, paraffin-embedded crosssections of P. westermani adults were deparaffinized and incubated with polyclonal anti-recombinant hemoglobinase antiserum at a dilution of 1:100 and then incubated with HRP-labeled antibodies at a dilution of 1:1,000. Negative controls were incubated with pre-immunized rat sera. To develop color, slides were submerged in freshly prepared diaminobenzidine solution and counterstained with hematoxylin. They were then observed under a light microscope.

RESULTS

Sequence of hemoglobinase gene

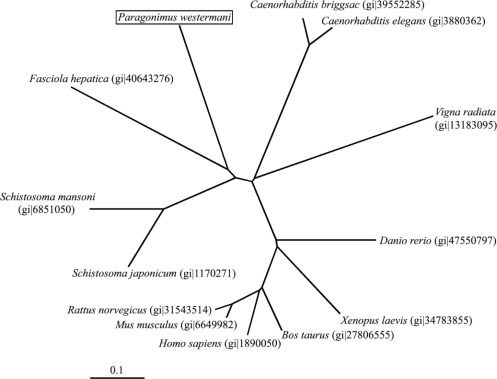

The hemoglobinase gene amplified from the cDNA library of P. westermani adults was found to contain a complete open reading frames consisting of 1,299 bp and encode a peptide of 355 amino acid residues with a calculated mass of 47 kDa. Fig. 1 shows the deduced amino acid sequences encoding the hemoglobinase. The constructed phylogenetic tree illustrated that the hemoglobinase gene shared high homology with hemoglobinases of Fasciola hepatica and Schistosoma spp. (Fig. 2).

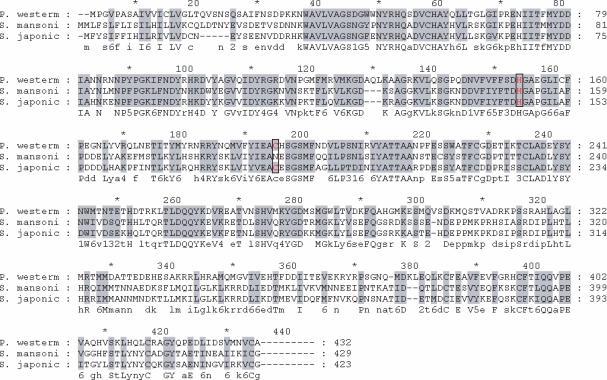

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence encoding the hemoglobinase of Paragonimus westermani. A full length hemoglobinase encodes 355 amino acids with a calculated mass of 47 kDa. The amino acid sequences of P. westermani, Schistosoma mansoni, and S. japonicum are shown for comparison. The His and Cys active site residues are boxed.

Neighbor-joining unrooted phylogenetic tree derived by aligning the amino acid sequences of the hemoglobinase with other hemoglobinase in the database. The hemoglobinase gene is 63% and 62% positively matched with the hemoglobinase of Fasciola hepatica and S. mansoni (Gene id is indicated in parenthesis).

Expression of recombinant P. westermani hemoglobinase

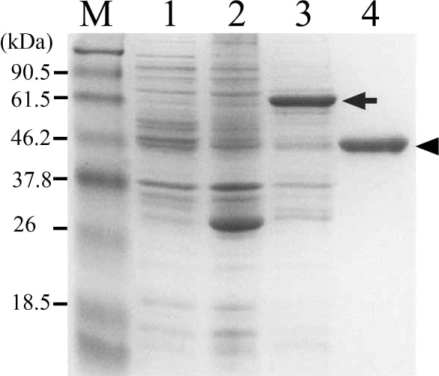

The expression of recombinant hemoglobinase in bacteria, E. coli strain BL21, resulted in high levels of hemoglobinase as visualized by Coomassie blue staining of whole bacterial lysates separated by SDSPAGE. Thick band of fusion proteins, at 73 kDa corresponding to hemoglobinase-GST fusion protein detected. The protein was expressed as inclusion bodies in bacterial lysates. To purify the recombinant hemoglobinase, hemoglobinase-GST fusion protein dissolved in sarcosyl and the band was confirmed to be located at their expected size (Fig. 3).

SDS-PAGE analysis of the recombinant hemoglobinase expressed in E. coli. Lanes: M, molecular mass standards; 2, lysates of BL21; 2, pGEX-4T1; 3, pGEX-4T1/hemoglobinase; 4, purified recombinant hemoglobinase (arrow indicates GST-hemoglobinase and arrow head indicates purified P. westermani hemoglobinase).

Hemoglobin hydrolysis assays

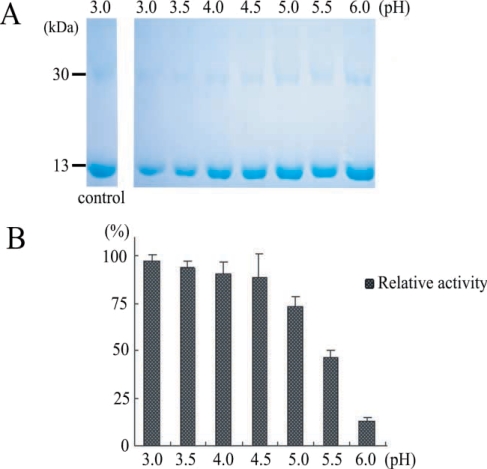

Protein activities were checked 4 times by hemoglobin degradation in sodium acetate buffer at pH (from 3.0 to 6.0) (Fig. 4). This result suggested that our purified enzyme might work in organs an acidic environment, such as, intestine, and that hemoglobinase was inhibited by E-64 (0.1 mg/ml) (Fig. 5). In addition, we confirmed that P. westermani hemoglobinase is a cysteine proteinase.

Degradation of human hemoglobin by recombinant hemoglobinase of P. westermani and relative activity under different pH conditions. A. SDS-PAGE of hman hemoglobin degradation by hemoglobinase. B. Relative activity of human hemoglobin degradation.

Properties of antibodies against hemoglobinase

Anti-recombinant hemoglobinase antibody was collected 6 weeks after immunizing 2 rats with recombinant protein. Immunoblot analysis showed positive reaction with their corresponding recombinant protein. Sera of experimental rats infected with P. westermani were collected and used to test the antigenicity of the recombinant hemoglobinase protein, by immunoblotting, the recombinant hemoglobinase showed a reactive band against the rat sera (Fig. 6).

Immunolocalization of P. westermani hemoglobinase

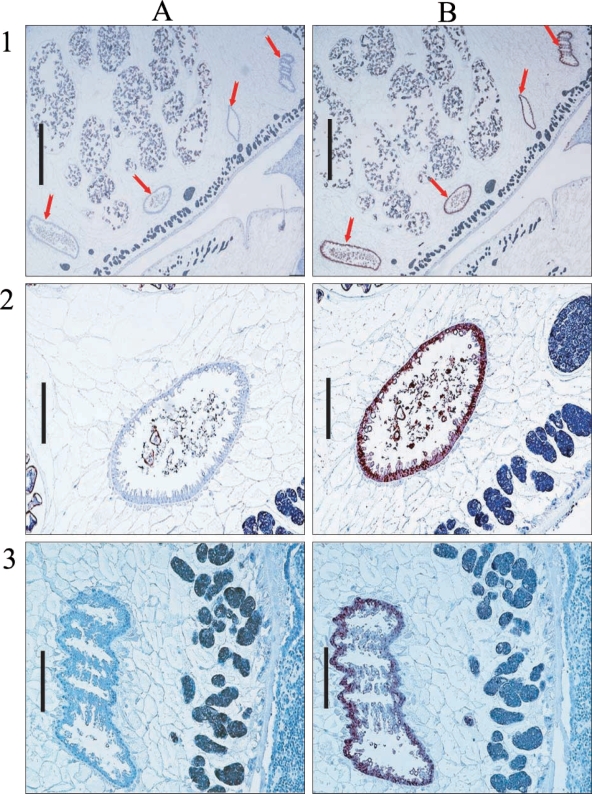

Hemoglobinase was localized in the epithelium of intestines in cross-sections of P. westermani adult by immunostaining (Fig. 7).

Immunohistochemical localization of hemoglobinase in P. westermani adult worm. Arrows indicate intestine of P. westermani. A. Immunohistochemistry with sera from nonimmunized rat for negative control. B. Immunohistochemistry with sera from rat immunized against the hemoglobinase. Bar = 1 mm in 1; 0.2 mm in 2 and 3.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we characterized a cDNA encoding a P. westermani hemoglobinase. Comparison of its amino acid sequence with hemoglobinases of other organisms revealed that it shared a high degree homology with hemoglobinases of trematodes, Fasciola hepatica and Schistosoma spp. (Merckelbach et al., 1994).

Highly conserved sequences of His and Cys were found in the hemoglobinase of P. westermani. Of the cysteine proteinases, papain family usually has His, Cys and Asp catalytic residues, but other cysteine proteinases lack Asp residues (Otto et al., 1997). Moreover, the activity of purified recombinant hemoglobinase of P. westermani was almost completely inhibited by cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64. These results indicated that this hemoglobinase is a type of cysteine proteinase.

P. westermani produces a number of classes of cysteine proteases in its developmental stages for various purposes. The diverse biological roles of the enzymes include metacercarial excystment (Chung et al., 1995), host immune evasion by cleaving human IgG (Chung et al., 1997), host tissue invasion (Na et al., 2006), and nutrient uptake from the host (Hamajima et al., 1985). The hemoglobinase showed specific activity toward host hemoglobin. P. westermani would uptake the host blood during its life. It has been reported that RBC is essential for the development of Paragonimus (Hata et al., 1987). P. westermani hemoglobinase would digest hemoglobin of the host RBC to provide essential nutrients especially amino acids and iron for worm development as hemoglobinases in other organisms do (Becker et al., 1995; Sijwali et al., 2001; Serrano-Luna et al., 1998).

Recombinant hemoglobinase of P. westermani was able to degrade hemoglobin at acidic pH values, from 3.0 to 5.5. The pH of the P. westermani intestine is not clearly defined yet, however, intestinal contents of a related blood-feeding helminth, S. mansoni, were reported to be acidic (Caffrey et al., 2004). Moreover, all of the proteinases in hookworms identified from this anatomic site had acidic pH optima (Williamson et al., 2002, 2003; Loukas et al., 2004). The hemoglobin digestive activities of hookworm secretory extracts were also optimal at pH 5-7 (Brown et al., 1995). Given these results, the purified enzyme would function in acidic environments.

Interestingly, recombinant P. westermani hemoglobinase did not degrade other extracellular matrix proteins, such as, collagen, fibrinogen, fibronectin, or natural blood proteins like IgG (data not shown). A similar result was reported in S. mansoni, which was found to contain a hemoglobinase that did not show any ability to degrade other natural blood proteins, and which led to the suggestion that this proteinase was responsible for hemoglobin degradation in the schistosome digestive tract (Bernhard et al., 1993).

As their various functions, cysteine proteinases of P. westermani have been reported to localize in various tissues of the worm, such as, the epithelia and luminal contents of the intestine (Yang et al., 2004), vitelline glands (Park H et al., 2001), intestinal epithelium and parenchymal cells (Yun et al., 2000). In our immunohistochemical analysis of the hemoglobinase using polyclonal antibodies against recombinant protein, a positive signal was observed in the intestinal epithelium of the adult, which concurs with its expected pH optimum.

In conclusion, the identified cDNA clone was found to encode a P. westermani hemoglobinase. This hemoglobinase showed strong hemoglobin degrading activity under acidic conditions, and was found to be specifically localized in the adult P. westermani intestinal epithelium. Our results suggest that this hemoglobinase act as a digestive enzyme to acquire essential nutrients from host hemoglobin in the intestine of P. westermani.

References

Notes

This study was supported by a grant (E00016-R04-2003-000-10128-0) from the Korea Research Foundation.