Prevalence of head louse infestation among primary schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea: nationwide observation of trends in 2011–2019

Article information

Abstract

Head louse infestation is a significant public health problem across the world, particularly among preschool and primary schoolchildren. This study investigated the trends of head louse infestation in the Republic of Korea over a 9-year period (2011–2019), targeting primary schoolchildren in 3 areas of Seoul, 4 other large cities, and 9 provinces. A survey was administered annually by the health staff of each regional office (n=16) of the Korea Association of Health Promotion (KAHP). The branch offices of KAHP examined a total of 51,508 primary schoolchildren, comprising 26,532 boys and 24,976 girls. Over the 9-year survey, a total of 1,107 (2.1%) schoolchildren tested positive for adults and/or nits of Pediculus humanus capitis. The prevalence was 2.8% (133/4,727) in 2011–2012 and gradually decreased to 0.8% (49/6,461) in 2019 (P<0.05). Head lice were found more frequently in girls (3.0%; 746/24,976) than in boys (1.4%; 361/26,532) (P<0.05). In terms of geographic localities, the highest infestation rate, 4.7% (average prevalence over 9 years), was observed in southern Seoul (Gangnam branch of KAHP), whereas the lowest infestation rate, 0.7%, was seen in Gyeongsang (north and south provinces) and western Seoul. Although the prevalence decreased significantly during the 9-year period, head louse infestation remains a health and hygiene issue among primary schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea. Regular surveys along with health education are needed to further improve children’s hair hygiene.

Introduction

Three species of Pediculidae are among the external parasites in humans; Pediculus humanus capitis, Pediculus humanus humanus, and Phthirus pubis [1]. Infestations of P. humanus capitis are primarily caused by physical contact with humans or objects, such as hair and combs; they can cause severe itching and skin diseases on the head [2]. P. humanus capitis has a long history of infestation across the world, including being found in ancient human mummies and hairbrushes from approximately 10,000 years ago [3].

Head louse infestation has been a common problem in developed and developing countries and primarily affects children aged 4–13 years [4,5]. It is associated with factors, such as race, age, sex, hair characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, occupation, and literacy of parents (including the educational level of the mother), frequency of washing hair per week, resistance to pesticides, and regional factors [6–8]. It can cause considerable social distress, discomfort, and embarrassment to the child, anxiety to the parents, and disruptions in work or school life [4].

The prevalence of P. humanus capitis was 13.0% in children aged 4–12 years in Australia [9], 35.0% in children aged 0–15 years in Brazil [10], 50.0% in women in Thailand [11], 52.9% in children aged 7–14 years in Ukraine [12], and 67.3% in schoolgirls aged 7–12 years in a low-income area in Iran [13]. Generally, the prevalence of head louse was 0.7–59.0% in the Asian population, 0.48–22.4% in Europeans, 3.3–58.9% in Africans, and 3.6–61.4% in Americans [14].

In the Republic of Korea, researchers have reported the prevalence of head louse infestation in primary schools, mental health hospitals, and public welfare facilities [15–22]. The prevalence among schoolchildren in urban areas was 16.6–41.5% and 35.7–70.3% in urban and rural areas, respectively, from 1985 to 1994; however, it decreased to 3.2–5.0% and 10.6–12.8% in urban and rural areas, respectively, from 1995 to 2004 [22]. From 2007 to 2008, the average prevalence was 4.1% among 15,373 kindergarten and primary schoolchildren, with a prevalence rate of 3.7% and 4.7% in urban and rural areas, respectively [22]. Girls had a higher infestation rate (6.5%) than boys (1.9%) [22]. Thereafter, no further reports have been available regarding the prevalence of head louse infestation among young children in the Republic of Korea. This study investigates the trends in head louse infestation among primary schoolchildren from 2011 to 2019.

Materials and Methods

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health Research of the KAHP (IRB no. 130750-202009-HR-020). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of each child, guardians, and/or the school principal.

Participants

Based on the reports that P. humanus capitis mainly affects children living in groups [15–22], this study involved a total of 51,508 schoolchildren, including 26,532 boys (51.5%) and 24,976 girls (48.5%), all over the country (except islands) from 2011 to 2019. Surveys were conducted annually by regional offices (n=16) of the KAHP in Seoul (western, eastern, and southern), main cities (Incheon, Daegu, Busan, and Ulsan), and the provinces of Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Chungcheong (north and south), Jeolla (north and south), Gyeongsang (north and south), and Jeju. The staff of each regional office randomly selected 3–5 schools, and the students were then tested using the direct detection method for head lice (adults and/or nits) using a fine-toothed comb. The test was conducted by an expert proficient in screening for ectoparasites, in cooperation with a health teacher under the approval of the parents, guardians, and schoolmasters.

Diagnosis of head louse infestation

For an accurate diagnosis, adult lice, and nits (alive), were carefully combed from the scalp to the ends of the hair. Observation of live adult worms was the basic criterion for a positive diagnosis. However, adult worms can crawl away quickly 6–30 cm per min [21] and can be difficult to see; therefore, the examiners carefully observed the nits to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis. Typically, P. humanus capitis adult females spawn nits within 6 mm from the scalp [21]. The spawned nits are immobile and easily spotted on the nape and behind the ears. However, the examiner needs to distinguish live nits from empty nits and foreign bodies such as dandruff, scabs, dirt, and other insects that are sometimes mistaken for nits. The nits are glossy, yellowish-white, and oval, with a length of about 0.8 mm [23]. A morphological criterion for living nits was whether they contain internal contents.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a chi-square test to compare qualitative variables; P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The overall prevalence of head louse infestation among schoolchildren was 2.1% (Table 1). The prevalence appeared to persist in 2011–2016 with minor changes that were not significant (P>0.05) (Table 1). However, from 2017 to 2019, the prevalence decreased abruptly; the decrease was significant (P<0.05) (Table 1). The highest prevalence was found in 2013–2014, with an average infestation rate of 3.1%, and the lowest was found in 2019, with a rate of 0.8%. In terms of gender, the prevalence was significantly higher in girls (3.0%) than in boys (1.4%) (P<0.05) (Table 1). We compared the prevalence of head louse infestation by 2 age groups, represented by school grades, 1–3 and 4–6 grades; however, the difference was not significant (data not shown).

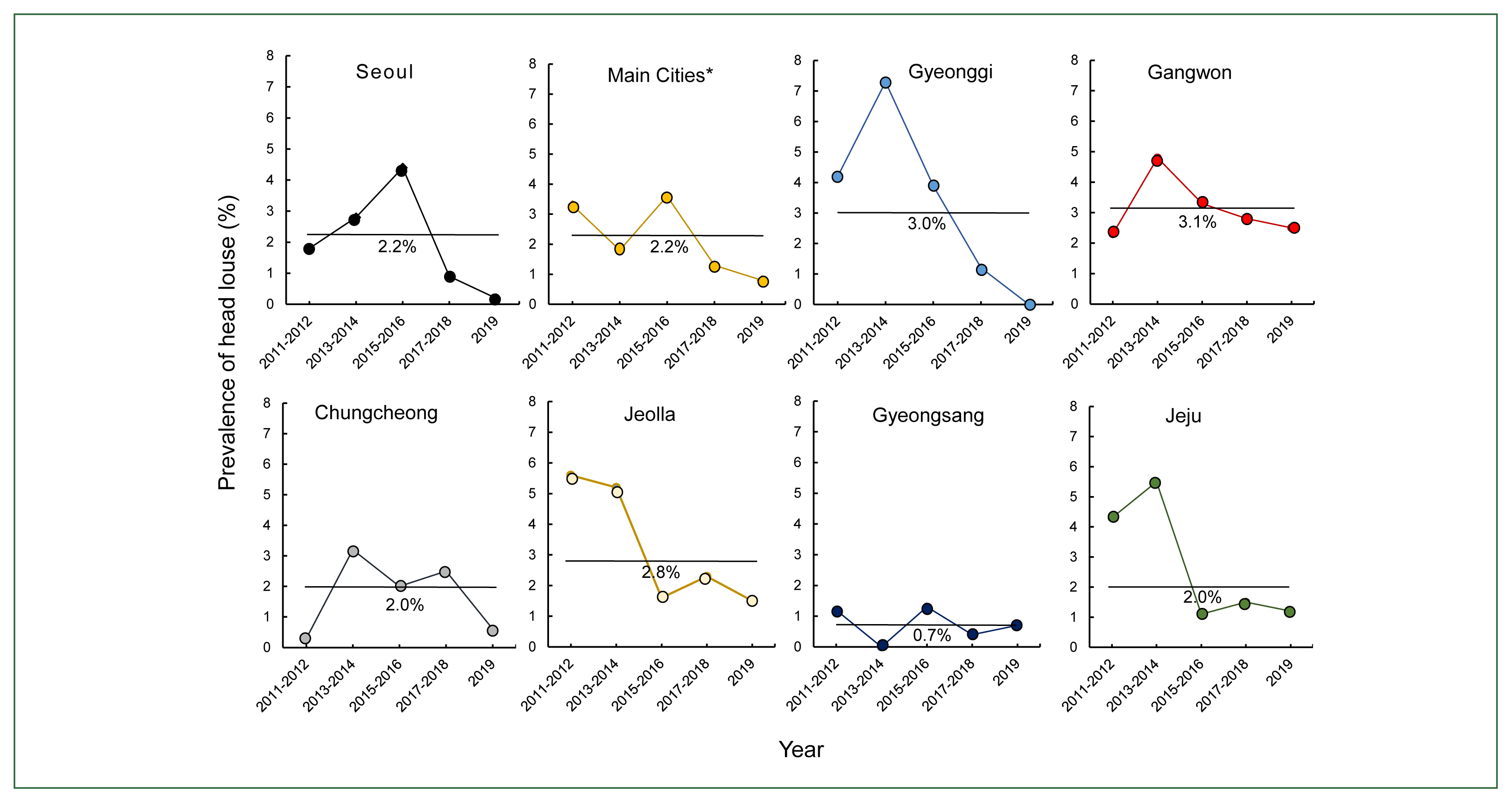

The infestation rates of schoolchildren in each region varied considerably from as low as 0% (Gyeongsang, 2013–2014; Gyeonggi, 2019) to as high as 7.3% (Gyeonggi, 2013–2014) (Fig. 1). The most significant decrease was seen in Gyeonggi, followed by Jeju and Seoul (3 areas combined) over the 9 years of the survey (Fig. 1). However, the differences in infestation rates by area were not significant (P>0.05). In terms of the average infestation rate during the 9 years by area, the rate in Gangwon was the highest at 3.1% followed by Gyeonggi at 3.0%, and the rate in Gyeongsang was the lowest at 0.7% (Fig. 1).

Geographic variation in the prevalence of head louse infestation among primary schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea during the 9-year period. Gangwon (3.1%), Gyeonggi (3.0%), and Jeolla (2.8%) showed the highest mean prevalence (horizontal lines), whereas Gyeongsang (0.7%) showed the lowest mean prevalence.

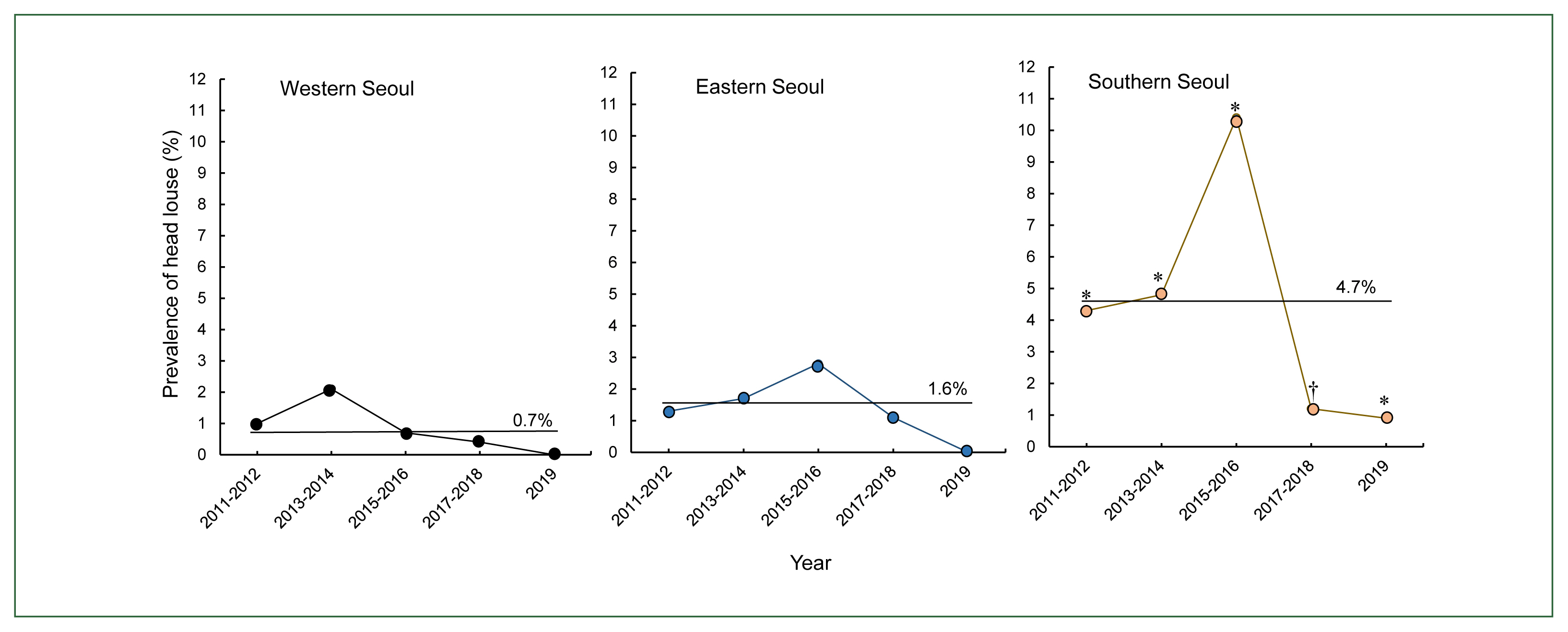

The average infestation rate of schoolchildren in Seoul (3 areas combined) from 2011 to 2019 was 2.2% (225/10,209), which was not remarkably different from the rate in other areas (Fig. 1). However, the average infestation rate in southern Seoul was 4.7% which was markedly higher than in the other 2 areas of Seoul (0.8% in western and 1.6% in eastern Seoul) and other areas (Fig. 1). A high prevalence was found from 2011 to 2016 in southern Seoul (Fig. 2). Particularly, in 2015–2016, the prevalence in southern Seoul reached 10.4% (95/915) (Fig. 2), which was the highest average prevalence observed during this survey. Overall, the prevalence in southern Seoul was significantly higher (P<0.05) than in the western and eastern areas of Seoul throughout the survey, except in 2017–2018 (Fig. 2).

The prevalence of head louse infestation among primary schoolchildren in 3 localities of Seoul during the 9-year period. Significant differences were noted in the prevalence between western and southern Seoul (*P<0.05), and between eastern and southern Seoul, through all periods (*P<0.05) except for 2017–2018 (†P>0.05).

Discussion

Head lice, a type of insect, are obligate ectoparasites, with 6 legs and no wings, and they reach 2–4 mm (adults) in length. They live in human heads (hair) and suck blood from the skin [24]. Moreover, they can transmit febrile diseases, such as epidemic typhus, trench fever, and relapsing fever [15]. They can also cause severe itching and secondary bacterial infections due to skin damage. A recent report suggested that head lice and body lice can cause bacterial infection of Bartonella quintana among homeless persons in the USA [25]. Hence, from a public health point of view, head louse management is an important issue.

Head lice have continued to be a prevalent issue from the past to the present, especially among children. They spread rapidly to other individuals through physical contact. When an infected person interacts in a community, a group infestation may rapidly occur. Thus, the prevalence of head louse is believed to differ significantly across different social groups. Periodic examinations, efforts to improve the environment, and preventive measures are necessary to prevent and manage head louse infestations.

This study found that the prevalence of head louse infestation among schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea declined over the past 9-year period. The average prevalence during the 9 years was 2.1% and decreased every year from 2.8% in 2011–2012 to 0.8% in 2019. Further, there was a gender difference in the prevalence, with a prevalence of 3.0% in girls and 1.4% in boys, which was not very different from previous reports [22]. This gender difference may be due to gender-specific behavioral differences, such as the condition and length of hair and various home and school environments. Regarding the geographic region, the average infestation rate over the 9-year period was the highest in southern Seoul (4.7%) followed by Gangwon (3.1%) and Gyeonggi (3.0%), and the lowest rate (0.7%) was observed in Gyeongsang and western Seoul. This finding is considered to be due to regional factors, such as the socioeconomic status and behavior of the people.

The most interesting finding in this study was that the prevalence of head louse infestation was the highest in southern Seoul, whereas it was lower in the western and eastern regions of Seoul. The rate grew steadily higher in southern Seoul in 2011–2016 and reached a peak (10.4%) in 2015–2016, and then decreased thereafter (2017–2019). The high prevalence in southern Seoul is difficult to explain. We believe that this temporary peak was due to a small outbreak of head louse infestation at the time in the surveyed primary schools. It can be postulated that the personal hygiene of schoolchildren at that time may have been lacking for unknown reasons. Further, there may have been increased contact with infected individuals (e.g., infected immigrants in schools from other localities). We regret that further in-depth investigation could not be performed. However, the prevalence decreased and became as low as the other areas in 2017–2019.

The current prevalence of head louse infestation among schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea is not so high compared to that in other countries. In Iran, the prevalence has varied according to participant groups; from 10.25% in primary school students in Ardabil Province [26] to 67.3% in primary school girls aged 7–12 years in a low-income area [13]. In Ukraine, the prevalence among children was 85.0% in 1990 but decreased thereafter to 52.9% among children aged 7–14 years [12]. In Thailand, the prevalence in 1981–2017 ranged from 15.1% to 86.1% in different areas; in 3 rural areas surveyed recently, the prevalence was 50.0% in women and 3.0% in men [11]. In Brazil, the prevalence among children aged 0–15 years from 11 institutions, including day-care centers, and public urban and rural schools, in Uberlândia was 35.0% [10]. In Australia, 13.0% of children aged 4.5–12 years in Victoria revealed active pediculosis in the hair and 3.3% had past treated or inactive infestations [9]. In the USA, an estimated 6 to 12 million cases occur annually, and a survey of elementary schoolchildren from kindergarten to fifth grade in Atlanta reported a prevalence of 5.2% for lice and/or nits (1.6% with adult lice and 3.6% with nits only) [27].

It is noteworthy that the situation of head louse infestation seems to have been favorably influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic [5,28]. In Israel, the use of pediculicides on children progressively increased during 2010–2019; however, it suddenly dropped in 2020 when COVID-19 became severe [5], probably due to social distancing, school closures, and improvement in individual hygiene. Similarly, in Poland, the social restrictions applied during the pandemic significantly reduced the number of infested schoolchildren compared to before the pandemic [29]. However, this could be a temporary phenomenon, and the prevalence of head louse infestation may become worse after the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, the average prevalence of head louse infestation as of 2019 was 0.8% nationwide. Several factors may have contributed to the decline in the prevalence. One factor may be the decrease in the number of children in primary schools. Wide usage of shampoo-type anti-head louse agents is believed to be another factor, alongside the general improvement of personal and institutional hygiene in primary schools. Nevertheless, caution should be paid to head louse infestation because once it occurs in a child it can spread quickly among the group of children. Continuous monitoring in cooperation with health workers, homes, schools, and the government is required to successfully manage head louse infestation among children in the Republic of Korea [29].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all schoolchildren who participated in this study and their parents, guardians, and directors of schools who kindly consented to this study. We are also grateful to the staff of regional offices of the KAHP who visited the schools and helped with the detection of head louse infestations.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Park JY, Lee J, Nah EH, Lee EH, Chai JY

Data curation: Ryoo S, Hong S, Chang TH, Shin H, Jung BK

Formal analysis: Ryoo S

Investigation: Hong S, Shin H

Methodology: Ryoo S, Park JY, Lee J

Project administration: Lee EH

Software: Ryoo S, Hong S

Supervision: Lee J, Nah EH, Lee EH, Chai JY

Validation: Park JY, Lee J, Nah EH, Lee EH, Jung BK

Visualization: Ryoo S, Chang TH

Writing – original draft: Ryoo S

Writing – review & editing: Jung BK, Chai JY

We have no conflicts of interest related to this study.