A surgically confirmed case of breast sparganosis showing characteristic mammography and ultrasonography findings

Article information

Abstract

A case of breast sparganosis was confirmed by surgical excision of a worm (fragmented into 5 pieces) in a 59-year-old Korean woman suffering from a palpable mass in the left breast. Mammography and ultrasonography characteristically revealed the presence of several well-defined, isodense and hypoechoic tubular masses, in the upper quadrant of the left breast, each mass consisting of a continuous cord- or worm-like structure. During surgery, a long segment of an actively moving sparganum of Spirometra sp. and 4 small fragments of the same worm, giving a total length of 20.3 cm, were extracted from the upper outer quadrant of the left breast and the axillary region. The infection source remains unclear, because the patient denied ingesting any snake or frog meat or drinking untreated water.

INTRODUCTION

Spargana are the plerocercoid larvae of a pseudophyllidean tapeworm that belongs to the genus Spirometra (Beaver et al., 1984). These larval tapeworms only very rarely grow to the adult stage in the human body (Lee et al., 1984), but the larval stage can cause an infection, namely, human sparganosis (Cho et al., 1974, 1975). Human sparganosis is contracted by eating raw or improperly cooked flesh of snakes or frogs infected with the plerocercoid larvae, by topically applying snake or frog skin to sore eyes, or drinking water contaminated with cyclops harboring the procercoid larvae (Beaver et al., 1984).

Human sparganosis cases are reported worldwide, but are more common in Asia, particularly Korea, China, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Thailand (Beaver et al., 1984). In Korea, 3 human cases were reported for the first time in 1924 (Kobayashi, 1925), but more than 100 cases were subsequently documented before the end of the 1980s in the Republic of Korea (Cho et al., 1975; Min, 1990). The patients were distributed nationwide, although more cases were reported in the northern parts of the Republic of Korea (Min, 1990). Moreover, seroepidemiologic observations in the normal adult population and in epileptic patients revealed high antibody positivities of 1.9% and 2.5%, respectively (Kong et al., 1994). The major reasons why snake meat is consumed in the Republic of Korea are due to the misconception that snake meat is an aphrodisiac, and because it is viewed as field food during military survival training (Cho et al., 1974, 1975; Min, 1990).

Radiological (Chung et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2005; Koo et al., 2006) and serological (Kong et al., 1994) techniques can provide useful diagnostic clues of sparganosis. However, in the case of breast sparganosis, radiological images closely resemble those of a neoplasm or granulomatous mastitis (Jeong et al., 1995; Chung et al., 1995; Moreira et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2005). Nevertheless, if a case shows characteristic, though not specific, mammography and ultrasonography findings, these helpfully raise suspicions of breast sparganosis.

We encountered an interesting case of breast sparganosis that showed characteristic mammography and ultrasonography findings. The diagnosis was later confirmed by surgical excision of the worm.

CASE RECORD

A 59-year-old Korean woman, a housewife residing in Seoul, with palpable masses in the left breast of 2 years duration, visited a local clinic, and was suspected as having a soft tissue tumor. She was transferred to a university hospital and then to the Korea Cancer Center Hospital. The patient had a clinical history of hormone replacement therapy some 10 years previously. Except for the palpable breast masses, physical examinations revealed no other abnormalities. She had a good consciousness and nutritive condition, and routine hematological, urinal, and chemical investigations were normal. No active lesion was observed by chest X-ray.

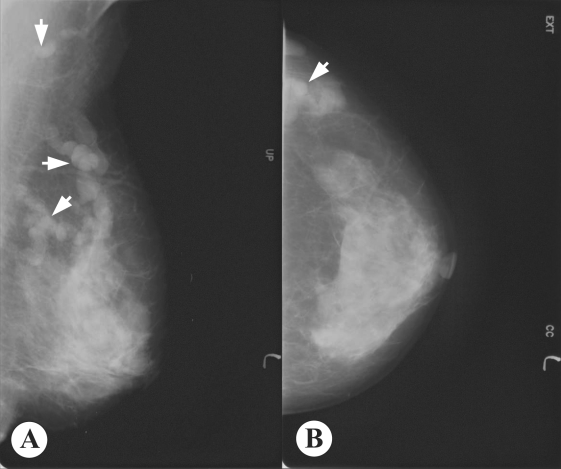

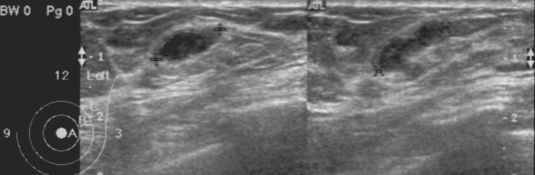

Mammography showed multiple, well-defined, isodense, lobular, and continuous cord-like structures in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast (Fig. 1). Ultrasonographic findings also showed well-defined, hypoechoic, tubular masses with folded band-like tracts and a tubule-in-tubule appearance, in the parenchymal layer of the left breast (Fig. 2). A neoplastic disease could not be ruled out, and therefore, fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed on the breast mass, which showed no evidence of neoplastic diseases. Then, breast sparganosis was suspected.

Mammogram of the present breast sparganosis case. A: Mediolateral oblique view, B: Craniocaudal view. Welldefined, isodense, lobular, and continuous cord-like structures (arrows) were characteristically observed in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast.

Ultrasonograms of the present sparganosis case, showing a well-defined hypoechoic, tubular mass with internal heterogeneous echogenicity, and tubule-in-tubule appearance in the subcutaneous layer of the upper outer quadrant of the left breast.

For an etiological diagnosis and treatment, left breast tissue was surgically excised. In resected tissue, a lesion with focal fibrosis, without definite mass formation, was observed and histopathologically confirmed as a fibrocystic disease. In the left side of the fibrotic cyst, a long tapeworm segment (Fig. 3), 12.0 cm × 0.7 cm in size, was found across the upper outer quadrant of the left breast toward the axillary region, and carefully extracted. The presence of a scolex was confirmed in this segment. In addition, 4 more fragments of the same worm of 3.3 × 0.8 cm, 1.7 × 0.7 cm, 1.6 × 0.8 cm, and 1.7 × 0.8 cm (Fig. 3), were collected from around the fibrotic cyst. All 5 extracted segments showed active movement, and were fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin solution for morphological identification. The worm was identified as a sparganum of Spirometra sp., and had a total length of 20.3 cm. The patient denied ingesting snake and frog meat, and drinking untreated water.

DISCUSSION

Spargana have the ability to migrate to any part of the human body (Cho et al., 1975; Min, 1990), including the brain (Anders et al., 1984) and oral cavity (Iamaroon et al., 2002). However, predilection sites include the abdomen (38 cases; 28.1%), urogenital organs (30; 22.2%), extremities (24; 17.8%), central nervous system (16; 11.9%), chest (14; 10.4%), and the orbital region (11; 8.1%); based on an analysis of 135 cases reported before 1987 in the Republic of Korea (Min, 1990). Breast sparganosis is rare, i.e., only 2 of these 135 cases (Jung et al., 1981; Nha et al., 1987). However, since 1987, 18 breast cases have been reported (Chi et al., 1988; Choi et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1992; Park and Hwang, 1992; Jeong et al., 1995; Chung et al., 1995; Park et al., 1996; Chang et al., 2000; Sim et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003). Therefore, the present case becomes the 21st reported case of breast sparganosis in the Republic of Korea; reported cases are briefly summarized in Table 1.

Sparganosis cases with fragmented worm segments in tissue, as in the present case, are uncommon, though infections with multiple worms are not uncommon. Seo et al. (1964) reported a case with 3 worms in the left lower scrotal area, where spargana are frequently found. Park et al. (1986) also observed a case with 4 worms in the scrotum and inguinal region. Cho et al. (1975) reviewed 60 sparganosis cases; 44 had only one worm, 6 with 2 worms, 4 with 3 worms, and the remaining 6 had 4-12 worms. However, in cases of breast sparganosis, only 1 worm has been reported in most patients (Table 1). In our case, 5 worm segments were recovered from the upper quadrant of the left breast and axillary region. All of these segments were actively motile after excision, and thus initially we believed that there were 5 distinct worms. However, careful observation confirmed them to be worm segments from a single worm, the longest of which was equipped with the scolex and neck portion (Fig. 3).

With regard to the source of infection, Min (1990) summarized the past histories of sparganosis patients and noted that the majority of patients had experience of eating various kinds of animal fleshes including snakes and frogs, and that some of the patients had drank untreated water. Moreover, although the likelihood of drinking untreated water is probably similar for men and women, the eating of snakes or frogs is likely to be far more common in men, which concurs with a known disease gender preference, i.e., men, 94 of 119 cases, and women, 25 of 119 cases (Min, 1990). With regard to breast sparganosis, patients reported in the Republic of Korea to date have all been females. Moreover, the majority have denied eating snake or frog meat, which leaves the source of infection in these cases obscure (Table 1). Also in the present case, the mode of infection was unclear, since the patient denied eating any snake or frog meat or drinking untreated water. Thus, the source of sparganum infection in female patients without a history of exposure to known sources should be clarified.

Breast sparganosis presents as soft tissue nodules, as in the present case, and is confused with neoplastic masses in radiological images (Chuen-Fung and Alagaratnam, 1991; Jeong et al., 1995). For example, its mammographic features are usually multiple, lobular, marginated, amorphic, and solid masses without calcifications, which are similar to the features of the circumscribed breast cancer or benign tumor-like fibroadenoma (Chung et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2005). Thus, a confirmatory diagnosis should be established by extracting the worm responsible or by examining surgical pathology specimens. However, as shown in the present case, mammography findings can be characteristic and highly useful for a pre-operative diagnosis of breast sparganosis.

Ultrasonographic findings may also be useful for the pre-operative diagnosis of breast or other organ sparganosis (Chung et al, 1995; Cho et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2005). In breast sparganosis, elongated, folded, band- or tunnel-like hypoechoic tubular structures in heterogenous, hyperechoic masses are characteristic (Chung et al., 1995), whereas in subcutaneous and musculoskeletal sparganosis, serpiginous, cystic, tubular tracts, with internal anechogenicity and posterior echo enhancement, are important characteristics (Cho et al., 2000). Intraluminal lesions formed by the larvae or debris and peritubular echo changes produced by chronic inflammatory reactions have been noted in a half of musculoskeletal sparganosis cases (Cho et al., 2000). However, findings of elongated, serpiginous, and tubular structures may also be obtained in other types of diseases, such as, ectatic ducts, radiation edema, superficial thrombophlebitis, and congestive heart failure (Chung et al, 1995; Kim et al., 2005). Nevertheless, such findings together with high antibody titers against sparganum, and characteristic mammography and ultrasonography findings will be very useful for a pre-operative diagnosis of sparganosis.

References

Notes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation [R05-2002-000-00808-0(2002)]