Abstract

Thelazia callipaeda, a parasitic nematode that causes thelaziosis in various mammals, including humans, is known to be endemic in Korea. However, life cycle-related information on the parasite, primarily from human infection and a few dog cases, is limited. This study reports additional cases of T. callipaeda infections in dogs from both rural and urban areas in Korea, indicating the potential for transmission to humans and other animals. We collected 61 worms from 8 infected dogs from Paju and Cheongju Cities and observed their morphological characteristics under a light microscope. The findings indicate that T. callipaeda infections in animals in Korea may be underestimated and are distributed close to human environments. Our results contribute to the growing knowledge of the reservoir hosts of T. callipaeda in Korea and highlight the importance of continued surveillance and research to prevent and control this emerging zoonotic disease.

-

Key words: Thelazia callipaeda, rural town, dog, definitive host, reservoir host, Korea

Thelazia callipaeda Railliet and Henry, 1910 (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) is a parasitic nematode of the family Thelaziidae that affects the orbital cavity of various mammals [

1]. This parasitic infection causes a disease called thelaziosis or thelaziasis in its final hosts, including humans. The clinical manifestation of thelaziosis range from minor ophthalmological problems such as foreign body sensation and itching to chronic follicular conjunctivitis related to corneal ulceration [

1–

3]. The life cycle of

T. callipaeda is maintained through a 2-step host, with drosophilid flies acting as the intermediate host. Adult females release larvae into the lacrimal secretions of final hosts, which develop into third-stage (L3) larvae inside drosophilid flies that swallow the lacrimal secretions. The infection is acquired when the fly attaches to the eyes of other definitive hosts [

1,

2].

Thelazia callipaeda, commonly referred to as the “oriental eyeworm”, has primarily been reported in East Asian countries and Korea is one of the endemic areas [

1,

4–

6]. However, information related to definitive hosts, especially the reservoir hosts in Korea, has been limited. The current study aims to report additional cases of reservoir hosts for

T. callipaeda in Korea, including dogs raised in the rural town of Cheongju-si (city), Chungcheongbuk-do (province), and cases from a companion animal clinic in Paju-si, Gyeonggi-do. We provide case descriptions along with morphological data of the species.

The neutering plan was decided to conduct for dogs from a small town in Myoam-ri (village), Munui-myeon (township), Cheongju, Korea, in April 2021 as part of a volunteering program for rural dog health care. Three male dogs were selected for castration. The first dog was physically restrained by its owner. Anesthesia was administered using a combination of tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazepam hydrochloride (2.5 mg/kg) by intramuscular injection. Several nematodes were occasionally exposed to the corneal surface of each eye while a lubricant was used to protect the dog’s eyes (

Fig. 1). The nictitating membranes were lifted using blunt-edged forceps, and the adjacent areas of the conjunctival sacs were investigated to find additional worms. Like the first dog, 2 more dogs were confirmed as parasite-positive among the additional 5 dogs examined. The other 5 dogs were mixed breeds, except for the first dog, which is a Golden retriever. A total of 14 nematodes were recovered from the 3 dogs (9, 4, and 1 worm, respectively). They were rinsed with physiological saline, preserved in 70% ethyl alcohol, and transferred to the Department of Parasitology, School of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea for parasitological analysis.

A veterinarian from a clinic in Paju-si, Gyeonggi-do stored small whitish nematodes collected from the orbital cavities of dogs in 10% neutral buffered formalin and provided them to laboratory. All 5 vials containing 47 worms were collected from 2017 to 2021, from individual dogs (

Table 1).

Worms were identified through observations of the morphological characteristics and measurements of morphometric features using a light microscope (BX53, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were cleared with lactophenol solution, and placed on the slide glass with cover slip before being observed under the light microscope. Specimen measurement used 9 of 19 worms isolated in Cheongju and 37 of 47 worms isolated in Paju among the 61 worms collected from 8 dogs.

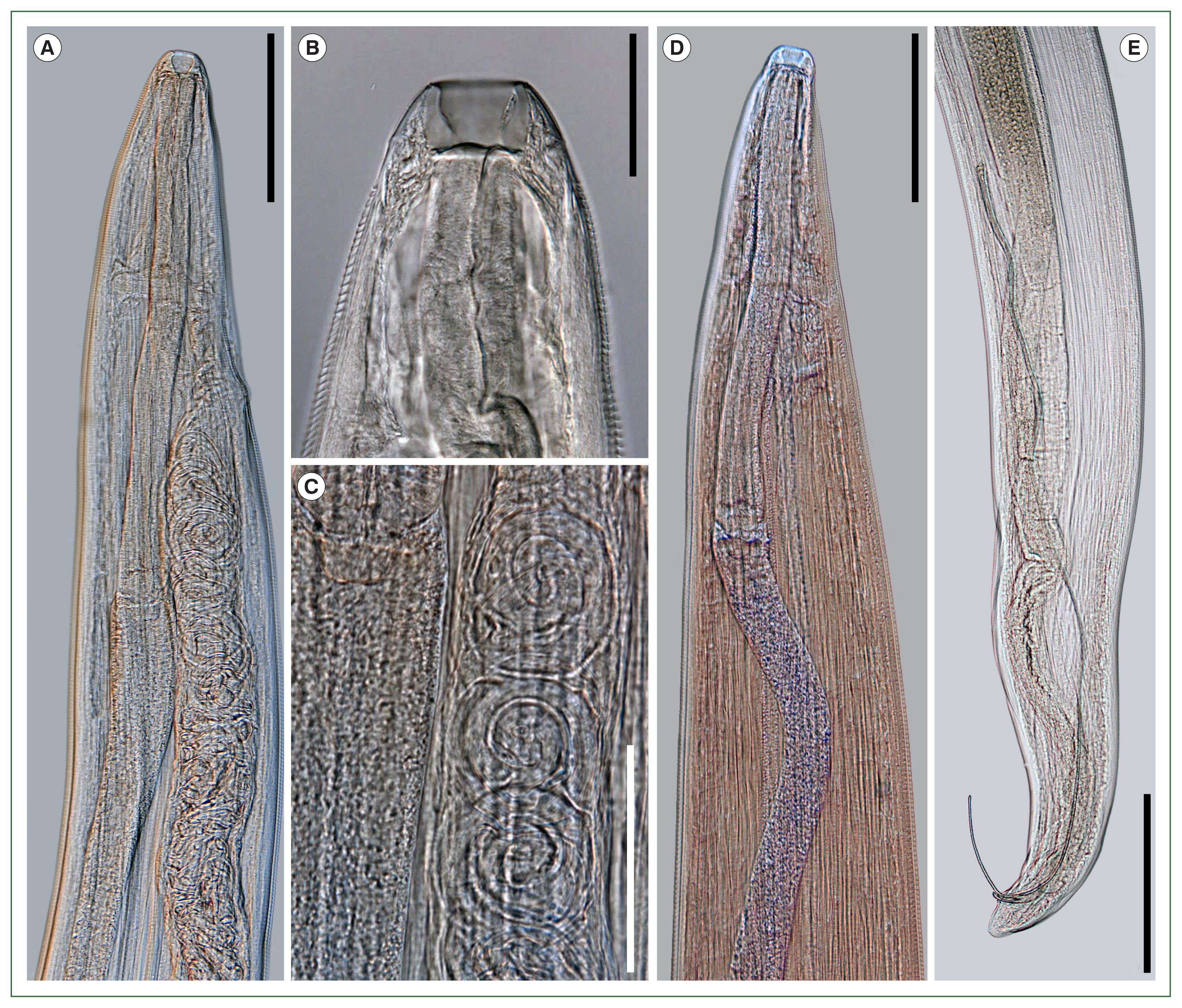

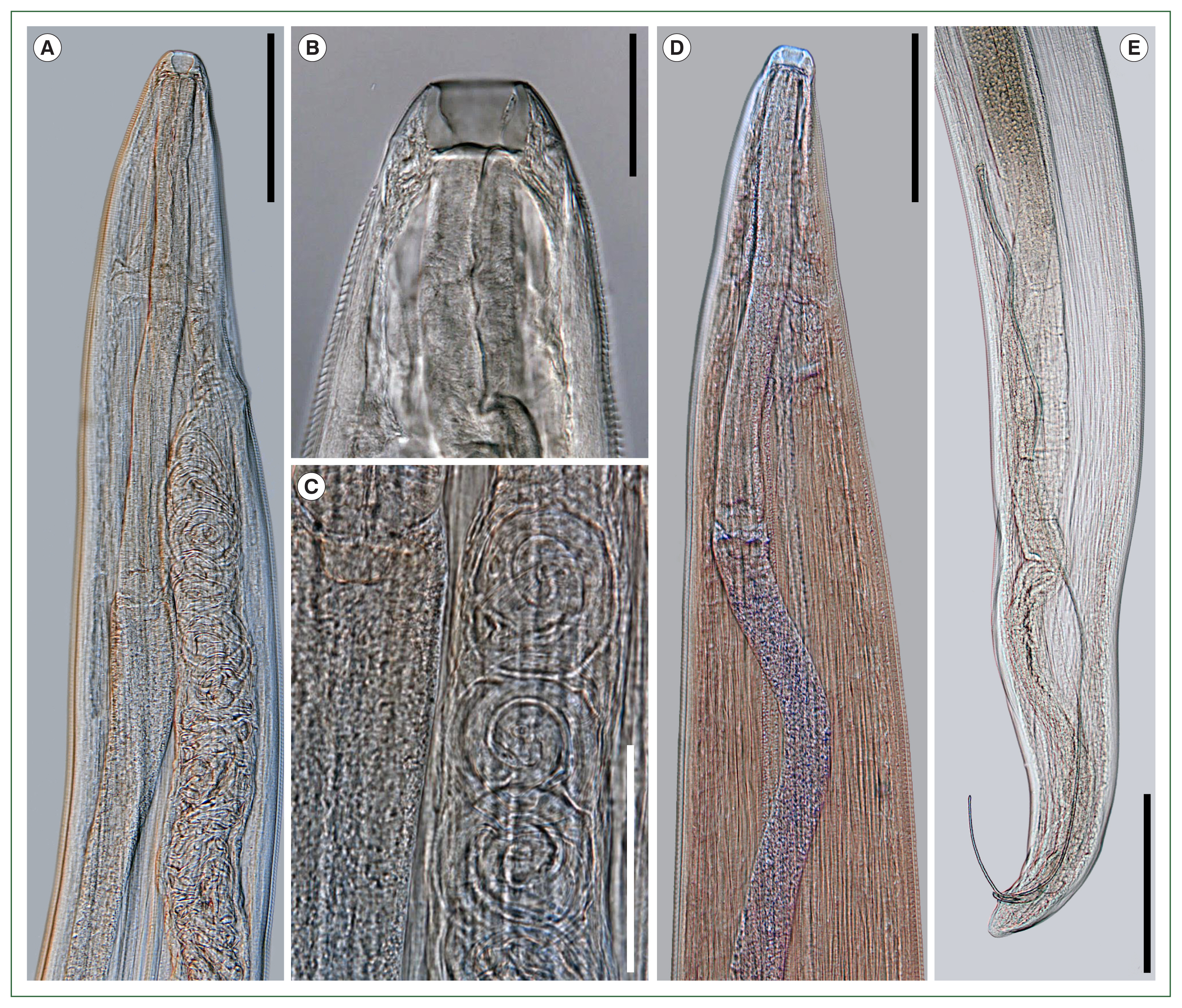

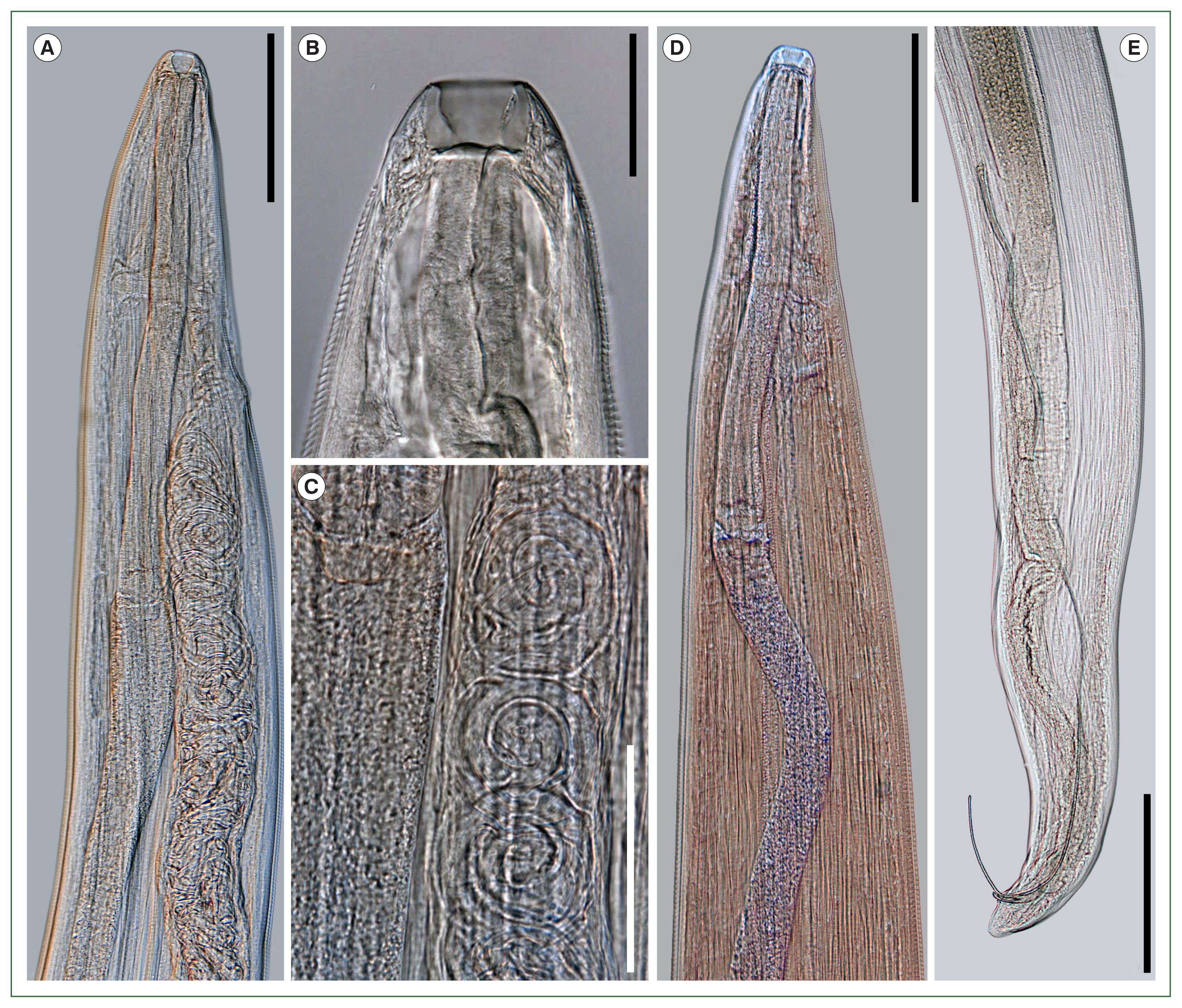

All of the specimens shared critical morphological characteristics well-fitted with the known characteristics of the genus

Thelazia (

Fig. 2) [

7]. The specimens were recovered from the eyes of dogs and had a well-developed buccal capsule, muscular esophagus without a partition, cuticle striation, and a remarkably short tail. In female worm, the vulvar was located at the mid or posterior half level of the intestine and the uterus was filled with coiled larvae and eggs. Male spicules have markedly different size. Although the condition of the specimens prevented the observation of some features, we were able to identify. We identified 7–8 pairs of precloacal papillae and a few pairs of postcloacal papillae. We identified the specimens as

T. callipaeda based on the morphological features [

8].

Table 2 shows the morphometrical measurements.

Thelzia callipaeda is one of the neglected parasites in Korea. Cases of thelaziosis have been sporadically reported to date while the prevalence of other parasitic diseases, including soil-transmitted helminthiasis, has significantly decreased [

9,

10]. Reports on thelaziosis in Korea mostly focused on clinical cases of over 40 human infections to date [

11]. Recently, approximately 40 cases are known although more

Thelazia has been collected from humans because case reports are not made unless there is something new or unusual. However, other disease aspects are comparatively neglected, with only 4 cases of reservoir hosts that can maintain the life cycle of the parasite other than humans [

12–

15], and even the vectors that transmit the parasite to humans have not been documented.

This study is the fifth report on

T. callipaeda infection in dogs from Korea. Previous cases reported infected dogs limited to a single dog or military dogs in mass breeding sites [

12–

15]. The present cases are noteworthy for 2 reasons. First, the infection was detected in several dogs in a rural town, indicating that

T. callipaeda maintains its life cycle close to human habitation and poses a high potential for transmission to humans and other animals [

12]. Two of the 3 infected dogs were chained, indicating that they may have been infected at the site and that the intermediate host of

T. callipaeda was abundant in the dog’s environment. Second, a single veterinary clinic located in an urban area had multiple cases. The case of the veterinary clinic emphasizes that

T. callipaeda infections in animals in Korea may be underestimated. Five

T. callipaeda infection cases were identified despite being collected from a single clinic over 3 years, indicating a high prevalence of animal infections that have yet to be recognized. Moreover, the reported 40 cases of human infection indirectly suggest that the number of animal infections could be even higher. Sohn et al. [

11] reported that the majority of the infections were from Seoul and Gyeonggi-do (28 cases), while the remaining cases were reported from other parts of the country (11 cases). The higher number of reported cases in Seoul and Gyeonggi-do is not necessarily indicative of higher infection rates but may be due to the abundance of academic facilities and trained personnel, who may be more aware of the infection and able to report it, as well as higher levels of outdoor activity among residents in these areas [

11]. Unfortunately, the research on parasitic diseases has been plagued by issues, such as underreporting of infections and insufficient scientific investigation of certain diseases, such as the case of canine myiasis [

11,

16]. The infections have been solely treated as diseases without proper documentation, which has hindered our understanding of these conditions.

A previous study mentioned that 146 individual nematodes were found in 39 cases of human infection with

T. callipaeda in Korea [

11]. The present study revealed 61 eyeworms from 8 infected dogs, with the number of worms varying between 1 and 22 (average: 7.6). Notably, the number of worms collected from the veterinary clinic represents only a fraction of the total number of infections. The higher individual worm burden of dogs than that in humans (between 1 and 15, an average of 3.7 [

11]) indicates that dogs may be more suitable hosts for

T. callipaeda than humans. This finding supports the notion that the infection status of dogs in Korea may be underestimated.

Therefore, the infection in reservoir hosts, such as dogs, should be controlled, to prevent human infection by

T. callipaeda and to halt its transmission and breeding. Further, other hosts involved in the life cycle, such as wildlife reservoirs and vectors, should be investigated. The known reservoir hosts of

T. callipaeda include a wide range of animals, from domestic dogs and cats to wildlife, such as fox, wolf, leopard cat, European wildcat, lynx, black bear, giant panda, hare, beech marten, and wild boar [

1,

17–

19]. Additionally, 2 species of drosophilid flies,

Phortica variegata and

P. okadai, have been recognized as the natural vectors of

T. callipaeda in Europe and Asia, respectively [

2,

17,

20]. Some of the known reservoir hosts and vectors of

T. callipaeda are distributed in Korea, such as foxes, wild boars, leopard cats, and

Phortica flies; thus, these animals and insects may act as hosts for the parasite in Korea.

This report presents T. callipaeda infection cases in 8 dogs from 2 different localities in Korea, contributing to the expanding body of knowledge on the definitive/reservoir hosts of this parasite in the country. We present morphometric data for T. callipaeda specimens obtained in this study. Our study was limited in its ability to conduct molecular analysis and obtain genetic data for T. callipaeda while the specimens collected were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Additionally, the symptoms from the parasites were not well described due to the mild (in Cheongju) to asymptomatic (in Cheongju and Paju) conditions of dogs in this study. Further studies should aim to investigate the currently limited information on T. callipaeda in Korea, including the possible involvement of wildlife hosts and vector-intermediate hosts. We emphasize the importance of continued surveillance and research on this emerging zoonotic disease.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Choe S, Kim JH Formal analysis: Kim S, Nath TC, Kim JH Funding acquisition: Choe S Investigation: Nath TC, Kim JH Methodology: Kim S, Nath TC Project administration: Choe S Resources: Kim JH Software: Kim S, Nath TC Supervision: Choe S Validation: Nath TC Visualization: Choe S Writing – original draft: Choe S Writing – review & editing: Choe S, Kim S, Nath TC

-

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Chungbuk National University Korea National University Development Project (2021). The authors thank all the participants who contributed to the volunteering program for the rural dog health care project, as well as a veterinarian from a veterinary clinic in Paju City, Korea, who preferred not to be named.

Fig. 1

Thelazia callipaeda Railliet and Henry, 1910 detected in the conjunctiva of a dog from a rural town in Cheongju City (arrow).

Fig. 2Photomicrographs of Thelazia callipaeda, recovered from dogs in the present study. (A) Anterior portion of female worm showing the uterus which is connected to the vulva located at the esophageal level. Bar=200 μm. (B) Anterior extremity of female worms showing well-developed buccal capsule. Bar=50 μm. (C) Encysted larvae in the uterus of female worms. Bar=100 μm. (D) The anterior portion of male worms. Bar=200 μm. (E) The posterior portion of male worms, showing the unequal size of spicules. Bar=500 μm.

Table 1Host information for Thelazia callipaeda infection cases in dogs from Paju city

Table 1

|

Date |

Breed |

No. of collection |

History |

|

2018. 04. 19. |

Golden retriever |

3 |

Stray dog |

|

2020. 08. 12. |

Yorkshire terrier |

3 |

Home breed |

|

2020. 08. 17. |

Border collie |

13 |

Home breed |

|

2021. 02. 02. |

Border collie |

22 |

Home breed, adopted from a stray dog shelter a week before visiting the hospital |

|

2017. |

Pug |

6 |

Unknown |

Table 2Measurements of

Thelazia callipaeda specimens collected from the present study

a

Table 2

Breed

Locality

Year |

Golden retriever

Cheongju

2021 |

Pug

Paju

2017 |

Golden retriever

Paju

2018 |

Border collie

Paju

2020 |

Yorkshire terrier

Paju

2020 |

Border collie

Paju

2021 |

|

Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number observed |

5 |

4 |

3 |

12 |

2 |

7 |

|

Body length |

11,309–15,063 (13,224) |

10,776–12,614 (11,320) |

9,475–14,675 (11,938) |

6,209–14,675 (7,997) |

7,779–13,735 (10,757) |

12,083–14,049 (13,106) |

|

Body width |

460–519 (490) |

425–555 (471) |

424–475 (441) |

381–475 (422) |

375–388 (382) |

440–479 (461) |

|

Buccal capsule length |

20–27 (23) |

22–41 (28) |

20–28 (25) |

18–28 (23) |

22–24 (23) |

22–31 (25) |

|

Buccal capsule width |

22–28 (24) |

22–30 (27) |

20–30 (25) |

20–30 (24) |

22–24 (23) |

18–29 (24) |

|

Esophagus length |

553–703 (612) |

559–628 (607) |

621–651 (637) |

389–651 (525) |

625–638 (631) |

526–664 (593) |

|

Nerve ring from anterior extremity |

226–317 (277) |

242–291 (262) |

262–268 (265) |

131–317 (248) |

229–291 (260) |

265–320 (289) |

|

Vulva opening from anterior extremity |

294–500 (408) |

366–451 (414) |

311–432 (389) |

232–468 (379) |

271–494 (383) |

301–533 (420) |

|

Tail length |

14–41 (29) |

37–43 (41) |

52–76 (67) |

19–76 (49) |

91–98 (94) |

11–73 (50) |

|

Male |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number observed |

4 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|

Body length |

9,247–10,535 (9,908) |

7,788–8,215 (8,002) |

- |

4,444 |

7,749 |

9,218–10,517 (9,834) |

|

Body width |

371–461 (424) |

387 |

- |

373 |

423 |

395–481 (430) |

|

Buccal capsule length |

19–25 (21) |

22 |

- |

20 |

20 |

21–23 (22) |

|

Buccal capsule width |

19–25 (22) |

24–25 (26) |

- |

22 |

24 |

22–24 (23) |

|

Esophagus length |

510–576 (537) |

461–494 (477) |

- |

396 |

644 |

468–559 (533) |

|

Nerve ring from anterior extremity |

216–284 (259) |

239 |

- |

265 |

324 |

229–317 (268) |

|

Right spicule length |

119–155 (138) |

132–141 (136) |

- |

138 |

144 |

115–130 (122) |

|

Left spicule length |

1,610–1,864 (1,710) |

1,864–2,273 (2,068) |

- |

1,740 |

1,775 |

1,697–1,995 (1,862) |

|

Tail length |

52–59 (56) |

59–76 (67) |

- |

16 |

95 |

65–92 (79) |

References

- 1. Anderson RC. Nematode parasites of vertebrates: their development and transmission. 2nd ed. CABI Publishing. Guilford, UK. 2000, pp 404-407.

- 2. Otranto D, Traversa D.

Thelazia eyeworm: an original endo and ecto-parasitic nematode. Trends Parasitol 2005;21(1):1-4.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2004.10.008

- 3. Marino V, Gálvez R, Montoya A, Mascuñán C, Hernández M, et al. Spain as a dispersion model for Thelazia callipaeda eyeworm in dogs in Europe. Prev Vet Med 2020;175:104883.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.104883

- 4. Bhaibulaya M, Prasertsilpa S, Vajrasthira S.

Thelazia callipaeda Railliet and Henry, 1910, in man and dog in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1970;19(3):476-479.

https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.476

- 5. Shen J, Gasser RB, Chu D, Wang Z, Yuan X, et al. Human thelaziosis-a neglected parasitic disease of the eye. J Parasitol 2006;92(4):872-875.

https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-823R.1

- 6. Otranto D, Lia RP, Traversa D, Giannetto S.

Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) of carnivores and humans: morphological study by light and scanning electron microscopy. Parassitologia 2003;45(3–4):125-133.

- 7. Chabaud AG. Keys to genera of the order Spirurida Part 1. Camallanoidea, Dracunculoidea, Gnathostomatoidea, Physalopteroidea, Rictularoidea and Thelazioidea. In Anderson RC, Chabaud AG, Willmott S eds, CIH Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham Royal. Bucks, UK. 1975, pp 1-27.

- 8. Kofoid CA, Williams OL. The nematode Thelazia californiensis as a parasite of eye of man in California. Arch Opthalmol 1935;13(2):176-180.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1935.00840020036002

- 9. Lee YJ, Kim SE, Kim JH, Paik JS, Yang SW.

Thelazia callipaeda infestation with tarsal ectropion. J Korean Opthalmol Soc 2020;61(3):294-297. (in Korean). https://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2020

- 10. Hong SH, Kim TH, Shi HJ, Eom JS, Park Y. A case of Thelazia callipaeda ocular infection identified in patient with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Korean J Healthc Assoc Infect Control Prev 2022;27(1):77-79. (in Korean). https://doi.org/10.14192/kjicp.2022.27.1.77

- 11. Sohn WM, Na BK, Yoo JM. Two cases of human thelaziasis and brief review of Korean cases. Korean J Parastiol 2011;49(3):265-271.

https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2011.49.3.265

- 12. Choi DK, Cho SY. A case of human thelaziasis concomitantly found with a reservoir host. J Korean Ophth Soc 1978;19(1):125-129. (in Korean).

- 13. Ryang YS, Lee KJ, Lee DH, Cho YK, Im JA, et al. Scanning electron microscopy of Thelazia callipaeda Railliet and Henry, 1910 in the eye of a dog. Korean J Biomed Lab Sci 1999;5(1):41-49.

- 14. Seo M, Yu JR, Park HY, Huh S, Kim SK, et al. Enzoocity of the dogs, the reservoir host of Thelazia callipaeda, in Korea. Korean J Parastiol 2002;40(2):101-103.

https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2002.40.2.101

- 15. Kim JT, Cho SW, Kim HS, Ryu SY, Jun MH, et al. Scanning electron microscopical findings of Thelazia callipaeda from a domestic dog. J Vet Sci CNU 2005;13:21-25.

- 16. Choe S, Lee D, Park H, Jeon HK, Kim H, et al. Canine wound myiasis caused by Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2016;54(5):667-671.

https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2016.54.5.667

- 17. Jin Y, Liu Z, Wei J, Wen Y, He N, et al. A first report of Thelazia callipaeda infection in Phortica okadai and wildlife in national nature reserves in China. Parasit Vectors 2021;14(1):13.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04509-0

- 18. Otranto D, Danta-Torres F, Mallia E, DiGeronimo PM, Brianti E, et al.

Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in wild animals: report of new host species and ecological implications. Vet Parastiol 2009;166(3–4):262-267.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.08.027

- 19. El-Dakhly K, El-Hadid SA, Shimizu H, El-Nahass S, Murai A, et al. Occurrence of Thelazia callipaeda and Toxocara cati in an imported European lynx (Lynx lynx) in Japan. J Zoo Wild Med 2012;43(3):632-635.

https://doi.org/10.1638/2011-0086R2.1

- 20. Otranto D, Lia RP, Cantacessi C, Testini G, Troccoli A, et al. Nematode biology and larval development of Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in the drosophilid intermediate host in Europe and China. Parasitology 2005;131(6):847-855.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182005008395