A case of disseminated strongyloidiasis diagnosed by worms in the urinary sediment

Article information

Abstract

Strongyloidiasis is a chronic infection caused by the intestinal nematode parasite Strongyloides stercoralis and is characterized by a diverse spectrum of nonspecific clinical manifestations. This report describe a case of disseminated strongyloidiasis with urination difficulty, generalized weakness, and chronic alcoholism diagnosed through the presence of worms in the urinary sediment. A 53-year-old man was hospitalized for severe abdominal distension and urinary difficulties that started 7–10 days prior. The patient also presented with generalized weakness that had persisted for 3 years, passed loose stools without diarrhea, and complained of dyspnea. In the emergency room, approximately 7 L of urine was collected, in which several free-living female adult and rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis, identified through their morphological characteristics and size measurements, were detected via microscopic examination. Rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis were also found in the patient’s stool. During hospitalization, the patient received treatment for strongyloidiasis, chronic alcoholism, peripheral neurosis, neurogenic bladder, and megaloblastic anemia, and was subsequently discharged with improved generalized conditions. Overall, this report presents a rare case of disseminated strongyloidiasis in which worms were detected in the urinary sediment of a patient with urination difficulties and generalized weakness combined with chronic alcoholism, neurogenic bladder, and megaloblastic anemia.

Introduction

Strongyloides stercoralis (Nematoda: Strongyloididae) is an intestinal nematode found globally, with more than 600 million people at risk of infection [1]. Humans become infected with the parasite when larvae penetrate the skin or are ingested. Once infected, these larvae migrate to the lungs via the bloodstream where they ascend the respiratory tract and are subsequently swallowed. Upon reaching the small intestine, they grow into parthenogenic females that lay eggs in the bowel, which hatch into rhabditiform larvae that are passed in the feces [2,3]. However, some larvae may transform into infective filariform larvae, which penetrate the intestinal mucosa and cause autoinfection [2,3].

Depending on the host’s immunity and parasite load, S. stercoralis can cause a wide spectrum of disease presentations, including acute or chronic strongyloidiasis, hyperinfection syndrome, and disseminated infection [2,3]. Disseminated strongyloidiasis is characterized by the migration of larvae to organs beyond the range of the pulmonary autoinfective cycle, allowing them to settle in ectopic sites including the skin, liver, brain, heart, and urinary tract [2,3]. The detection of parasites in urine is a relatively rare and nearly universally incidental finding but can be an important point of disease discovery in some cases [4–8]. Urinary strongyloidiasis has been reported in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder [4]; renal transplantation [5]; diabetes mellitus [6]; hypopharyngeal cancer receiving a combination of fluorouracil, cisplatin, and corticosteroids [7]; and hydronephrosis [8].

In Korea, human S. stercoralis infections have been reported sporadically and mainly involve cases of intestinal strongyloidiasis or Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome [9–11]. No case of S. stercoralis detected in urine samples has yet been reported. This report describes a rare case of disseminated strongyloidiasis in which worms were detected in the urinary sediment of a patient who presented with urination difficulties, severe abdominal distension, and generalized weakness combined with chronic alcoholism, neurogenic bladder, and megaloblastic anemia.

Case Description

A 53-year-old Korean man was admitted the emergency room of Chungnam National University Hospital with the chief complaints of abdominal distension and urination difficulties that started 7–10 days prior to visit. Approximately 3 years prior to visit, he developed generalized weakness. The patient also passed loose stools without having diarrhea and complained of dyspnea. Physical examination upon visit revealed an afebrile, ill-looking, and hypertensive male with generalized pitting edema. In the emergency room, approximately 7 L of urine was collected from the patient over 24 h using a Foley catheter, a portion of which was fixed with 10% formalin and transferred to the Department of Parasitology, Chungnam National University College of Medicine, since several parasites were recognized in the urinary sediment.

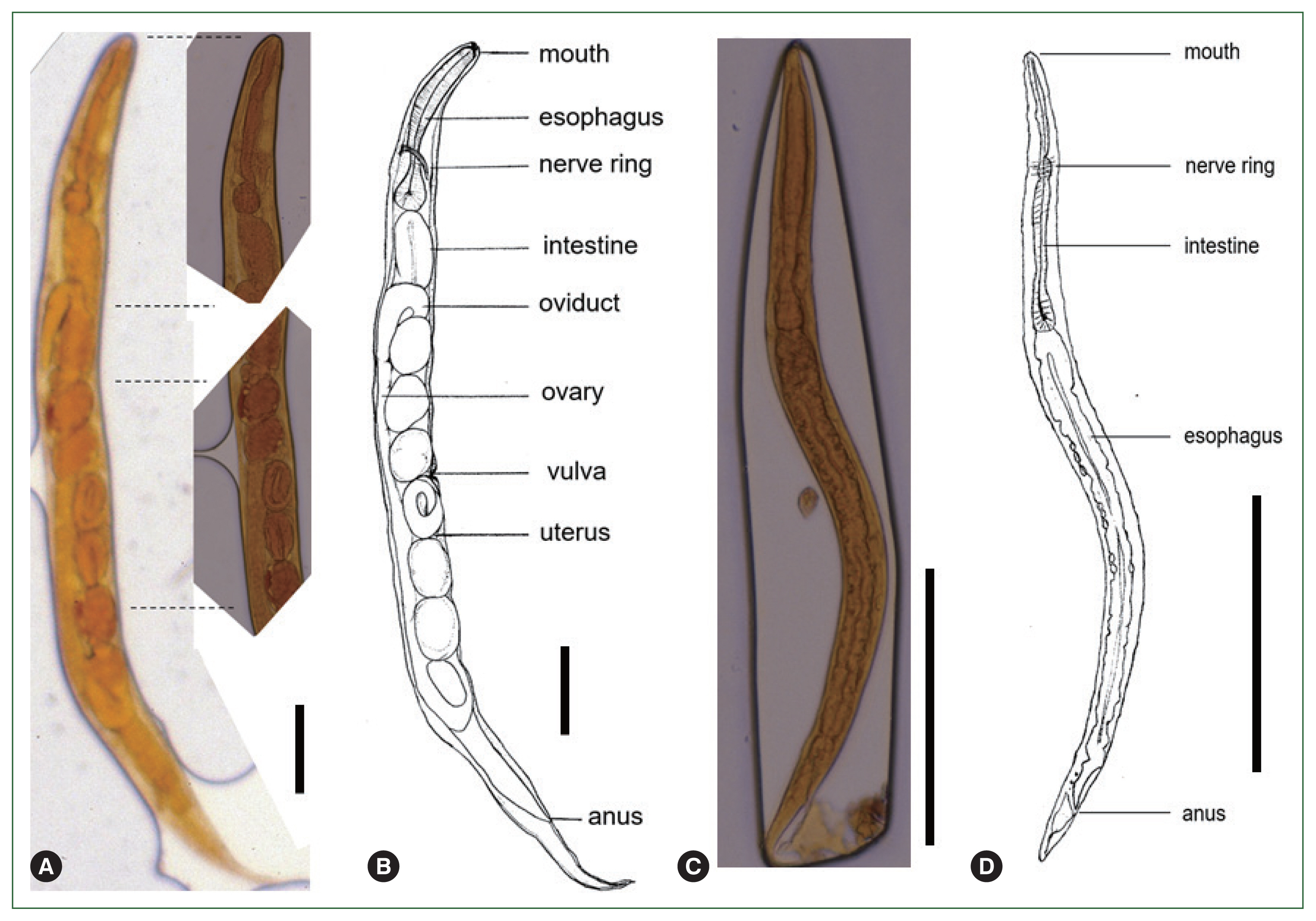

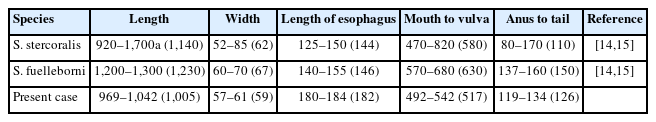

Several free-living female adult and rhabditiform larvae of nematode were found in the urine under microscopic examination. To identify the nematodes present in the urine, the morphological characteristics and sizes of free-living female adult worms and rhabditiform larvae were examined. In the free-living female adult worms, the mouth, esophagus, intestine, uterus, vulva, and anus were observed, and the eggs around the vulva contained larvae (Fig. 1A, B). Their mean length and width were 1,005 and 59 μm, respectively. Their esophagus was 182 μm long, front end (mouth) to vulva length was 517 μm, and anus to tail length was 126 μm long (Table 1). The larvae were elongated, with the esophagus being the most prominent organ under a microscope. The larvae measured 226–312 μm (mean: 244 μm) in length and 11–20 μm (mean: 16 μm) in width (Fig. 1C, D). Rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis were also found on stool examination.

Microscopic findings of Strongyloides stercoralis in the urine of the patient. (A) Free-living female adult of S. stercoralis. (B) Schematic description of a free-living female adult of S. stercoralis. (C) Rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis. (D) Schematic description of a rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis. Scale bar=100 μm.

Measurements of female adults in the free-living generation of Strongyloides species compared to those reported in previous studies

Human strongyloidiasis is mainly caused by S. stercoralis and to a lesser extent by Strongyloides fuelleborni [12,13]. Table 1 shows the previously reported measurements of free-living female S. stercoralis and S. fuelleborni [14,15]. Based on morphological characteristics and size measurements, the free-living female adult worms in this case were identified as S. stercoralis. Although the morphological characteristics of Rhabditis hominis nematodes are similar to those of S. stercoralis, female R. hominis adults, which have a length of 1.4–2 mm and width of 0.12 mm [16], are longer and wider than free-living female S. stercoralis adults in the current case.

Laboratory investigations revealed proteinuria, hematuria, hypoalbuminemia, and leukocytosis; however, the patient’s eosinophil count remained within the normal range. Cystoscopy and cystourethrography revealed no fistula between the urinary tract and intestine. During hospitalization, the patient received treatment for chronic alcoholism, peripheral neuritis, neurogenic bladder, megaloblastic anemia, and strongyloidiasis. He was discharged after improvement in his condition. For the treatment of S. stercoralis infection, the patient received albendazole 400 mg/day orally for 2 weeks.

Discussion

The discovery of S. stercoralis in urinary sediment may be caused by urinary specimen contamination from gastrointestinal infection or by urinary tract involvement of infection suggestive of disseminated disease. Thus, cystoscopy and cystourethrography were performed to examine parasitic contamination from the intestine; however, our findings revealed no fistula between the urinary tract and intestine. Several risk factors have been associated with the development of disseminated strongyloidiasis, including immune deficiency, hematologic malignancies, steroid administration, human T-lymphotropic virus-1 infection, chronic alcoholism, renal failure, HIV infection, diabetes, advanced age, and transplantation, among others [2,3,17]. In the present study, our patient complained of generalized weakness combined with chronic alcoholism, neurogenic bladder, and megaloblastic anemia. In our case, generalized weakness (or malnutrition) due to chronic alcoholism may have contributed to the development of disseminated strongyloidiasis. The increased susceptibility to S. stercoralis infections observed in alcoholic individuals could be attributed to their increased exposure to the parasite, malnutrition, breakdown of local immune responses, and alterations in intestinal barriers [3,18,19]. Moreover, ethanol intoxication can increase human endogenous corticosterone levels, which consequently suppresses T-cell function and increases parasite fecundity and survival [3,18,19].

The presence of S. stercoralis in the urine is quite rare and incidental finding. Notably, in the current case, free-living female adult and rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis were found in the urine. This event was presumed to have formed an intrarenal (or intravesicular) special autoinfection cycle in which filariform larvae developed into adult forms (parthenogenic females). In our case, urine remained stagnant in the bladder for days due to a neurogenic bladder and urination difficulties, which created a favorable environment for the sexual life cycle of S. stercoralis and facilitated egg production and subsequent expulsion of rhabditiform larvae in the urine. The same situation was observed in a case who developed intestinal constipation with S. stercoralis hyperinfection, in whom filariform and rhabditiform larvae, eggs, and free-living female adult of S. stercoralis were found in the stool [20]. Furthermore, several researchers have reported the presence of rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis in the urinary sediment of patients [4–8]. These reports, along with ours, indicate that both parthenogenetic and sexual reproduction may occur in S. stercoralis-infected hosts.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis has nonspecific clinical manifestations. Its onset is usually sudden with generalized abdominal pain, distension, and fever associated with indigestion, vomiting, diarrhea, steatorrhea, protein losing enteropathy, weight loss, cough, dyspnea, and others [2,3,17]. The present case developed loose stools, dyspnea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and hypoalbuminemia, similar to those observed in previous reports [2,3,17]. Eosinophilia is present in most cases of uncomplicated strongyloidiasis and in 50–80% of patients with mild infection. However, patients with Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis usually do not present with eosinophilia or have low eosinophil counts [21], which is consistent with the present case.

One limitation of this paper was that additional confirmation, such as molecular studies or new photography, are not possible due to the loss of the patient’s urine sample. Overall, the current report describes our experience with a rare case of disseminated strongyloidiasis combined with urination difficulties, persistent generalized weakness, chronic alcoholism, neurogenic bladder, and megaloblastic anemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research fund from Chungnam National University and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University (Approval number: 202304-BR-058-01) and with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013.

Notes

The author has no conflict of interest related to this work.

Conceptualization: Lee YH

Data curation: Lee YH

Formal analysis: Lee YH

Funding acquisition: Lee YH

Investigation: Lee YH

Methodology: Lee YH

Project administration: Lee YH

Supervision: Lee YH

Visualization: Lee YH

Writing – original draft: Lee YH