Delayed Human Neutrophil Apoptosis by Trichomonas vaginalis Lysate

Article information

Abstract

Neutrophils play an important role in the human immune system for protection against such microorganisms as a protozoan parasite, Trichomonas vaginalis; however, the precise role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of trichomoniasis is still unknown. Moreover, it is thought that trichomonal lysates and excretory-secretory products (ESP), as well as live T. vaginalis, could possibly interact with neutrophils in local tissues, including areas of inflammation induced by T. vaginalis in humans. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of T. vaginalis lysate on the fate of neutrophils. We found that T. vaginalis lysate inhibits apoptosis of human neutrophils as revealed by Giemsa stain. Less altered mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and surface CD16 receptor expression also supported the idea that neutrophil apoptosis is delayed after T. vaginalis lysate stimulation. In contrast, ESP stimulated-neutrophils were similar in apoptotic features of untreated neutrophils. Maintained caspase-3 and myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) in neutrophils co-cultured with trichomonad lysate suggest that an intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis was involved in T. vaginalis lysate-induced delayed neutrophil apoptosis; this phenomenon may contribute to local inflammation in trichomoniasis.

INTRODUCTION

Trichomonas vaginalis, a protozoan parasite which infects the vagina of women and causes vaginitis, is one of the common causes of non-viral sexually transmitted disease (STD) worldwide, especially in women who work in the commercial sex industry [1,2]. The pathogenesis of trichomoniasis in humans is not yet clearly understood, although T. vaginalis is known to be a non-invasive microorganism which recruits inflammatory cells to the infection site following genital tract surface attachment [3]. Meanwhile, many neutrophils were observed in the vaginal discharge of women with trichomoniasis and a known chemotactic cytokine, IL-8, secretion was observed after T. vaginalis stimulation [4,5]. It has been suggested that neutrophils migrate to the inflammatory site following infection with trichomonads and play an important role in protective mechanisms against the parasite.

Neutrophils have a short life span in the blood and undergo spontaneous apoptosis within 24 hr. During inflammation, a range of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1α, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or even acidic conditions function to prolong polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) life span [6-8].

Rapid onset of apoptosis in neutrophils and the subsequent engulfment of the apoptotic cells by phagocytes are important in the rapid resolution of inflammation. This is necessary to avoid unwanted tissue damage caused by activated neutrophils around the infection site [7,9]. It is known that delayed neutrophil apoptosis is associated with the pathogenesis of several diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease [10,11]. Aspirin (acetyl salicylic acid), an anti-inflammatory drug, counteracts the delay of neutrophil apoptosis by turning off survival signaling mediated by nuclear factor κB (NF-κB); as a result the inflammatory response is decreased [8].

In our previous report, live T. vaginalis induced human neutrophil apoptosis via a caspase-3 and Mcl-1 dependent manner using reactive oxygen species (ROS) [12,13]. However, the relationship between T. vaginalis lysate and the apoptosis of human neutrophils is still unclear. Moreover, it is thought that trichomonal lysates and excretory-secretory products (ESP), as well as live T. vaginalis, could interact with neutrophils in the local tissue around inflammation induced by T. vaginalis.

In the present study, we observed the alteration of neutrophil apoptosis during T. vaginalis lysate co-incubation to determine whether T. vaginalis lysate affects the inflammatory reaction of trichomoniasis. Our results suggest that T. vaginalis lysate induces the delay of human neutrophil apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway and thereby may contribute to local inflammation in trichomoniasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trichomonads

The human trichomonad, T. vaginalis, (T016 isolate), and the bovine trichomonad, Tritrichomonas foetus, were used for this experiment [14,15]. Trichomonads were axenically cultured every 24 hr in a glass tube containing complex trypticase-yeast extract-maltose (TYM) medium (pH 6.2 for T. vaginalis; pH 7.2 for T. foetus) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, New York, USA) in 5% CO2 in air at 37℃ [16]. The viability of the trichomonads was determined before each experiment using trypan blue staining (>99%).

Lysate of the trichomonads was prepared using the sonication method. Briefly, trichomonads in the log phase were harvested and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Trichomonad pellets were lysed by a sonicator (UP 50H, dr. hielscher GmbH, Teltow, Germany), then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was collected and used as a lysate of trichomonads after measuring the protein content using the Bradford method.

ESP of trichomonads was prepared by cultivating 1×107/ml trophozoites in a 12-well plate at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1 hr. The incubation medium was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min and filtered through 0.2 µm pore-sized filter paper before use.

Neutrophil isolation and culture conditions

The human neutrophils were isolated from healthy donors by the previously described method with a minor modification [5]. Freshly isolated neutrophils were suspended in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL). Viability of the neutrophils was determined by the trypan blue exclusion test (>99%). To measure neutrophil apoptosis, cells (5×105) were cultured with trichomonad lysate (100 µg/ml) in polypropylene tubes containing 1 ml of RPMI 1640/10% FBS and cultured at 37℃ up to 72 hr. In addition, neutrophils were treated with live T. vaginalis trophozoites (5×104; cell:trichomonad = 10 : 1), ESP of T. vaginalis (100 µ/ml), or T. foetus lysate (100 µg/ml) to investigate the influence of these various conditions of trichomonads on neutrophil apoptosis. The pro-apoptotic drug actinomycin-D (5 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was used to induce neutrophil apoptosis.

Light microscopy for apoptotic neutrophils

Apoptotic neutrophils were morphologically observed by light microscopy following Giemsa staining. After incubation with trichomonad lysate at the indicated time point, neutrophils (5×105) were centrifuged using a Cytospin centrifuge (Shandon, Loughborough, UK). Centrifuged cells were stained with Giemsa solution, then the apoptotic rate of the neutrophils was determined by counting the number of neutrophils with condensed nuclei [17].

Flow cytometric analysis for mitochondrial membrane potential and surface expression of CD16

Flow cytometric analysis was done after JC-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) staining to evaluate the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) of the neutrophils. Alteration of JC-1 aggregates (high MMP) and JC-1 monomers (low MMP) were measured using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany), and neutrophils with a low MMP were regarded as apoptotic neutrophils [13,18]. Surface CD16 receptor shedding was also used as a marker of neutrophil apoptosis [19]. Trichomonad lysate-stimulated neutrophils were stained with PE-labeled anti-human CD16 mAb (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, California, USA), then the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified by flow cytometric analysis. At least 5,000 neutrophils in each experimental group were selected and analyzed using CellQuest pro software (BD Pharmingen).

Western blot analysis for Mcl-1 and caspase-3 detection

The expression of the Bcl-2 family protein Mcl-1 and caspase-3 in T. vaginalis lysate-treated neutrophils was detected using Western blot analysis. After the indicated time of incubation, neutrophils (2×106) were lysed with 120 µl ice-cold lysis buffer composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM APMSF, 1% NP-40, and leupeptin (5 µg/ml), and all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The cellular proteins were subjected to SDS polyacrylamide gel (10% for Mcl-1, 15% for caspase-3 analysis) and Western immunoblotting was performed with mouse monoclonal anti-Mcl-1 Ab (1 : 200 dilution; Oncogene, San Diego, California, USA) or rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 Ab (1 : 100 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) on PVDF membranes. The blots were then incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG as a secondary Ab (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and the protein band was detected by ECL plus kits (Amersham Pharmacia) as described by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using means of the Mann-Whitney U-test using SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Significant difference was accepted at a P value of < 0.05.

RESULTS

Trichomonas vaginalis lysate inhibits spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis

After incubation of neutrophils in vitro with T. vaginalis lysate (100 µg/ml), neutrophil apoptosis was observed by light microscopy, fluorescent microscopy, and flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1A, T. vaginalis lysate-co-incubated neutrophils were shown to have a decreased rate of apoptosis compared to untreated neutrophils by counting neutrophils with condensed chromatin following Giemsa staining.

Influence of Trichomonas vaginalis lysate on the delay of human neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophils were incubated with T. vaginalis lysate (100 µg/ml) for 20 hr. Morphology of the neutrophils' nuclei was observed by Giemsa staining after cytocentrifuging (A). Arrows indicate neutrophils with condensed nuclei. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potentials were observed using a JC-1 probe (B). Arrows show changes of MMP with T. vaginalis lysate. Surface CD16 receptor shedding was observed by flow cytometry following anti-CD16 Ab staining (C). The data represent one of 3 separate experiments. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

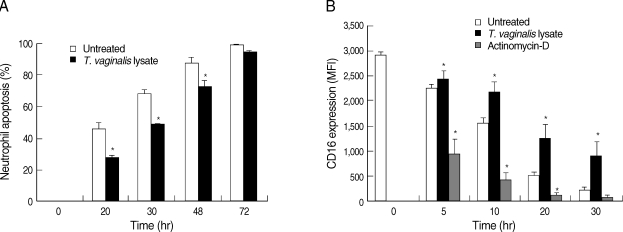

The membrane potential of mitochondria is known to be decreased in neutrophils during apoptosis [13]. To determine whether T. vaginalis lysate induces a delay of neutrophil apoptosis via a mitochondrial pathway, change of the MMP was observed with a JC-1 probe. In JC-1 staining, fluorescence was seen in both green (FL-1) and red (FL-2) channels. Alteration of MMP was determined by fluorescence changes from red (JC-1 aggregates; high MMP) to green (JC-1 monomers; low MMP). The neutrophils co-incubated with T. vaginalis lysate showed maintained low levels of MMP at 20 hr (Fig. 1B). The shedding of surface CD16 receptors is also known to be an early apoptotic change of neutrophils. The MFI of CD16 receptors was increased in T. vaginalis lysate-treated neutrophils compared with that of untreated and actinomycin-D treated neutrophils (Fig. 1C, Fig. 2B).

Neutrophil apoptosis over a 72 hr time period following Trichomonas vaginalis lysate stimulation. Neutrophils were co-cultured with T. vaginalis lysate for up to 72 hr. (A) At the indicated time points, cytospun neutrophils were stained with Giemsa and apoptotic cells were counted by light microscopy. (B) Surface CD16 receptor expression was determined with anti-CD16 Ab staining. Actinomycin D was used as a positive control for cell apoptosis. The data represent means ± SE of 3 separate experiments.

*P < 0.05; untreated neutrophils vs T. vaginalis lysate-treated neutrophils.

Spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils was increased with incubation time in the experimental culture. In this experiment, neutrophils were cultured for up to 72 hr and their apoptosis was observed with the passage of time. Giemsa staining revealed that neutrophil apoptosis increased with time, and condensed chromatin in trichomonal lysate-treated neutrophils was observed at a significantly lower rate (28.9%, 49.9%, and 67.3% at 20 hr, 30 hr, and 48 hr, respectively, P < 0.05) compared to untreated neutrophils (46.3%, 68.5%, and 87.8% at 20 hr, 30 hr, and 48 hr, respectively, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). However, there was no difference in neutrophil apoptosis irrespective of T. vaginalis lysate treatment after 72 hr of incubation.

Influence of parasite conditions on neutrophil apoptosis

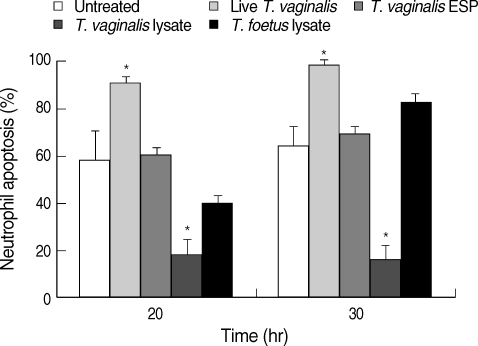

T. vaginalis infects the urogenital system of humans and recruits inflammatory cells to the infection site [3]. Besides live T. vaginalis, various statuses of trichomonads, such as weakened trophozoites fighting inflammatory cells, and ESP from trichomonads, could also influence the immune responses of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils at the site of trichomoniasis. To investigate this possibility, neutrophils were treated with live T. vaginalis, ESP from T. vaginalis, or lysate of T. vaginalis during incubation. Using light microscopy, we found that live trophozoites and trichomonal lysate significantly increase and decrease the rate of neutrophil apoptosis, respectively. However, ESP of trichomonads did not influence the life span of the neutrophils (Fig. 3).

Trichomonad lysate-induced neutrophil apoptosis in a species-specific manner. The neutrophils were co-cultured with live Trichomonas vaginalis, excretory-secretory products (ESP) of T. vaginalis, T. vaginalis lysate, or Tritrichomonas foetus lysate. Apoptotic rate was determined by light microscopy using Giemsa staining. The data represent means ± SE of 3 separate experiments.

*P < 0.05; untreated vs trichomonad-treated neutrophils.

While parasite infection is representative of zoonosis all over the world, each parasite infects their host in a species-specific manner. We observed changes of apoptosis in neutrophils treated with lysate of a bovine trichomonad, T. foetus, to verify these species-specific properties in trichomonads. Neutrophil apoptosis was not significantly reduced with T. foetus lysate treatment as observed using Giemsa staining (Fig. 3).

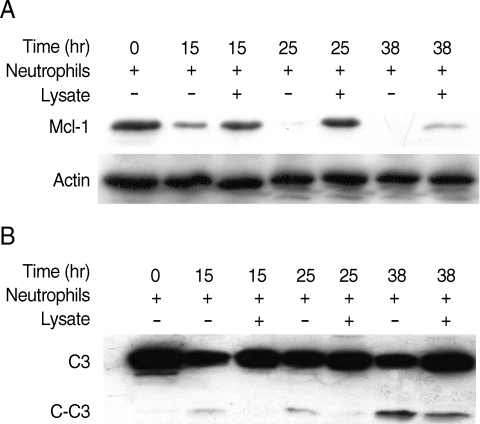

Involvement of Mcl-1 and caspase-3 on T. vaginalis lysate-induced reduced apoptosis

Cells were analyzed by Western blots using a previously described method to investigate the effect of Mcl-1 and caspase-3, key elements of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, on delaying neutrophil apoptosis induced by T. vaginalis lysate [12]. Mcl-1, an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, was maintained in T. vaginalis lysate-co-incubated neutrophils at 25 hr and decreased after 38 hr incubation. However, Mcl-1 expression in untreated neutrophils decreased after only 15 hr (Fig. 4A).

Involvement of Mcl-1 (A) and caspase-3 (B) in delay of neutrophil apoptosis induced by Trichomonas vaginalis lysate. After co-incubation of neutrophils with T. vaginalis lysate for 15, 25, and 38 hr, cells were electrophoresed for a Western blot analysis. One of the 2 separate experiments is shown. C3, caspase-3; C-C3, cleaved caspase-3.

Caspase-3, a cysteine protease, is activated by various pro-apoptotic signals [20]. In this experiment, treatment with T. vaginalis lysate reduced caspase-3 cleavage in neutrophils at 15 hr and 25 hr incubation. However, active caspase-3 (cleaved caspase-3) was shown in untreated neutrophils at 15 hr incubation (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

Neutrophil apoptosis delay was known to be associated with the pathogenesis of several diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [10]. At the site of trichomoniasis, clearance of aged or apoptotic neutrophils may help to protect normal tissues from the toxic molecules released by necrotic neutrophils. Our previous study suggested that live T. vaginalis increases neutrophil apoptosis; this may contribute to the resolution of inflammation via clearance of apoptotic neutrophils [12,13]. However, the T. vaginalis lysate used in this experiment decreases neutrophil apoptosis and may subsequently allow the initiation of inflammation.

Variously conditioned trophozoites, such as live, damaged, or attenuated parasites, and secretory molecules from T. vaginalis, could have an effect on immune responses around the site of inflammation. For example, trichomonads caused neutrophils to produce low levels of IL-8 compared to live T. vaginalis, and IL-8 may contribute to apoptotic changes of neutrophils [5]. IL-8 secretion was also observed with bacterial supernatant or Anaplasma phagocytophilum treated neutrophils, and apoptosis delay was also shown in these neutrophils [9,21]. Accordingly, it is suggested that a balance of viable trophozoites, lysates, and ESP form T. vaginalis may contribute to progression of inflammatory reactions in trichomoniasis via the control of neutrophil apoptosis.

Recent studies have reported that the response of host cells against microorganisms, including neutrophil apoptosis, is diverse because of the tremendous variation of these pathogens. An extract derived from intact Cysticercus cellulosae induces neutrophil apoptosis via intracellular ROS production. Entamoeba histolytica, a tissue invasive protozoan, induces neutrophil apoptosis via ERK1/2 and caspase-3 activation [22,23]. However, a water-soluble extract of Helicobacter pylori inhibits neutrophil apoptosis via Fas and TNF-R1 [24]. In the case of the obligate intracellular protozoans Leishmania major and Toxoplasma gondii, prolonged survival in host cells results from the inhibition of infected cell apoptosis [25,26].

The family of Bcl-2 proteins and the caspase cascade are related to the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Bcl-2 proteins stimulate the secretion of cytochrome c from mitochondria while cells excited by external and internal apoptotic signaling undergo apoptosis by way of caspase cascade activation and DNA fragmentation [27]. Also, neutrophils constitutively express a range of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins while anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins are expressed restrictively. In neutrophils, only Mcl-1 is reliably measured at both the mRNA and the protein levels [28]. Previous reports regarding the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins in neutrophils indicated that neutrophils do not express Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, but they do express Mcl-1. Therefore, it is speculated that Mcl-1 plays a role in the regulation of neutrophil apoptosis [7]. It has also been demonstrated that changes in cytokine or local oxygen levels control the survival time of neutrophils through regulation of cellular Mcl-1 levels [28]. For example, TNF-α (10 ng/ml) stimulation induces caspase dependent Mcl-1 turnover and eventually increases neutrophil apoptosis [29].

Since live T. vaginalis induced neutrophil apoptosis via Mcl-1 and caspase-3 in our previous studies, we decided to examine Mcl-1 and caspase-3 in neutrophils to investigate the related mechanism of T. vaginalis lysate-induced delayed neutrophil apoptosis [12,13]. As shown in Fig. 4A, Mcl-1 in T. vaginalis lysate-co-incubated neutrophils was maintained after 25 hr of incubation and at the same time point caspase-3 cleavage was reduced compared with untreated neutrophils. These results suggest that the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, including Mcl-1 and caspase-3, is involved in the delay of neutrophil apoptosis induced by T. vaginalis lysate. These results also correspond with the results of other studies which reported that Anaplasma phagocytophilum delayed neutrophil apoptosis via Mcl-1 and caspase-3 mechanisms [9].

Taken together, our results indicate that lysate of the human trichomonad, T. vaginalis, delayed human neutrophil apoptosis through inhibition of typical features of apoptosis such as decreased MMP, caspase-3 activation, and reduction of Mcl-1. These results are different from the influence of viable T. vaginalis trophozoites, which accelerated the rate of neutrophil apoptosis, and are also different from the action of ESP from T. vaginalis, which did not significantly influence neutrophil apoptosis. These data seem to explain how local inflammation is maintained and resolved in T. vaginalis infections. Moreover, further studies regarding detailed components of trichomonad lysate will help us further understand the nature of human infection by T. vaginalis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Anti-Communicable Diseases Control Program of the National Institute of Health (NIH 348-6111-215), Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.