Plasmodium vivax Malaria: Status in the Republic of Korea Following Reemergence

Article information

Abstract

The annual incidence of Plasmodium vivax malaria that reemerged in the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1993 increased annually, reaching 4,142 cases in 2000, decreased to 864 cases in 2004, and once again increased to reach more than 2,000 cases by 2007. Early after reemergence, more than two-thirds of the total annual cases were reported among military personnel. However, subsequently, the proportion of civilian cases increased consistently, reaching over 60% in 2006. P. vivax malaria has mainly occurred in the areas adjacent to the Demilitarized Zone, which strongly suggests that malaria situation in ROK has been directly influenced by infected mosquitoes originating from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). Besides the direct influence from DPRK, local transmission within ROK was also likely. P. vivax malaria in ROK exhibited a typical unstable pattern with a unimodal peak from June through September. Chemoprophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and primaquine, which was expanded from approximately 16,000 soldiers in 1997 to 200,000 soldiers in 2005, contributed to the reduction in number of cases among military personnel. However, the efficacy of the mass chemoprophylaxis has been hampered by poor compliance. Since 2000, many prophylactic failure cases due to resistance to the HCQ prophylactic regimen have been reported and 2 cases of chloroquine (CQ)-resistant P. vivax were reported, representing the first-known cases of CQ-resistant P. vivax from a temperate region of Asia. Continuous surveillance and monitoring are warranted to prevent further expansion of CQ-resistant P. vivax in ROK.

Malaria is the most prevalent parasitic disease in the world, with an estimated 500 million cases and 1-3 million deaths being annually attributed to this disease [1]. Plasmodium vivax, the causative agent of P. vivax malaria, is the second most common species among the 4 species of Plasmodium that can cause human malaria; an estimated 35 million P. vivax-transmitted malaria cases occur worldwide each year [2]. P. vivax malaria was endemic on the Korean Peninsula for many centuries until the late 1970s, when the Republic of Korea (ROK) was declared malaria-free [3]. During the Korean War (1950-1953), approximately 15% of all febrile illnesses among ROK Army personnel were due to malaria [4,5]. However, the incidence decreased steadily after the Korean War as socioeconomic conditions in ROK improved and associated malaria control efforts were strengthened, and ROK was finally declared malaria-free in 1979 [3]. However, focal indigenous cases that originated from imported cases continued to be reported until 1984 [6].

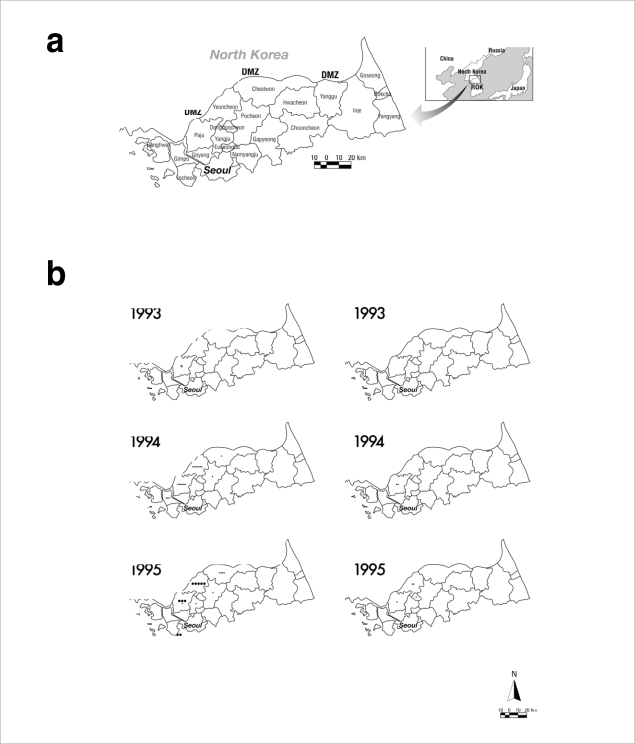

P. vivax malaria had not been reported in ROK until 1993, when the first reemerging case was diagnosed in a ROK Army soldier stationed in Paju County, which is located near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that divides ROK (South Korea) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK; North Korea) [7]. After its reemergence, the annual incidence of P. vivax malaria increased rapidly, reaching 4,142 cases in 2000 [7]. Although there was a decrease in the annual number of P. vivax malaria cases to 864 in 2004, it once again increased in 2005 and reached more than 2,000 cases by 2007 (Table 1) [8-10]. After reemergence, more than two-thirds of the total annual cases were reported among military personnel. However, the proportion of civilian cases increased consistently since the late 1990s, reaching over 60% in 2006 (Fig. 1) [7-10].

Annual incidence of Plasmodium vivax malaria among the Republic of Korea Army military personnel, veterans and civilians

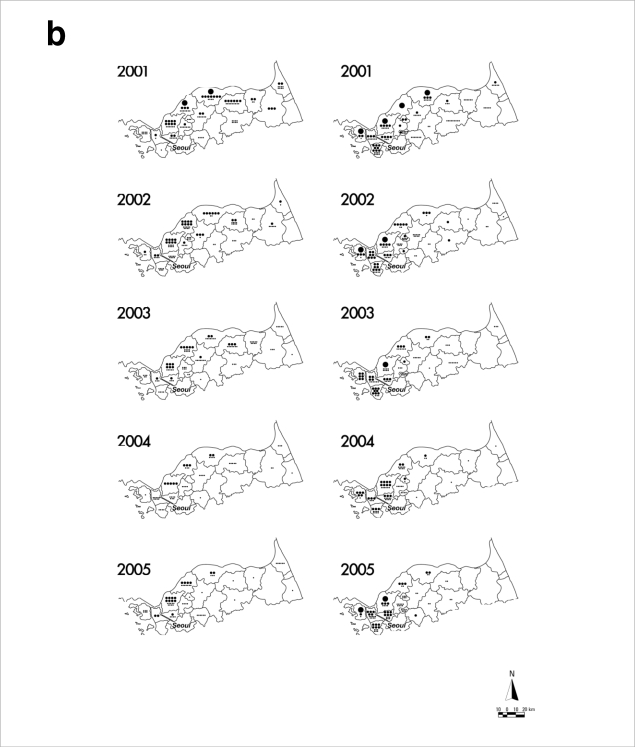

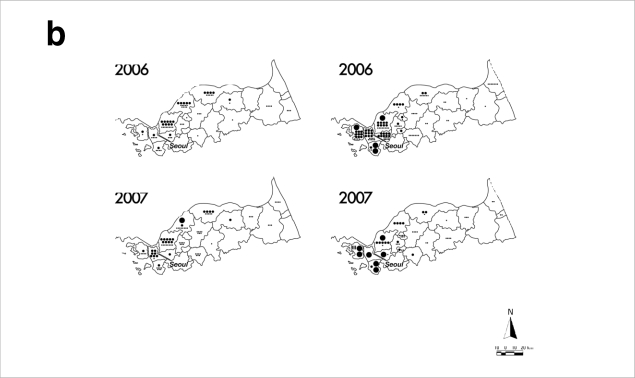

After reemergence in 1993, P. vivax malaria mainly has occurred in regions of ROK adjacent to the DMZ (Fig. 2) [7-10]. This epidemiological data strongly suggests that the P. vivax malaria situation in ROK has been directly influenced by infected mosquitoes originating from DPRK [11,12]. Soon after reemergence, P. vivax malaria mainly occurred in areas adjacent to the midwestern part of the DMZ (Gimpo and Paju Cities, Yeoncheon and Cheolwon Counties). From 1998-2000, when the annual incidence of P. vivax malaria in ROK peaked, the malaria-risk areas expanded to encompass large areas adjacent to the DMZ from Ganghwa to Yanggu Counties. P. vivax malaria also occurred in Goseong County located east of the Taebaeck Mountain Range during this period. However, malaria occurrence in Goseong County might have resulted from infected mosquitoes originating from the adjacent DPRK, and not from direct expansion from neighboring Yanggu County. Since 2001, the occurrence of malaria cases had decreased in most cities/counties located in the malaria-risk areas with reduction of the total annual incidence. However, P. vivax malaria continues to be problematic in the northwestern part of ROK including the cities of Gimpo, Incheon, Goyang, and Paju, and in Ganghwa and Yeoncheon Counties. Increase of the total annual incidence that has occurred since 2005 has been mainly due to the increased number of cases in these locales, which might be influenced by the malaria situation in DPRK. In the mid-2000s, regional incidences in some areas of the southwestern part of DPRK adjacent to the DMZ - a region harboring many rice fields that can be breeding grounds for mosquitoes-remained as high or even higher than in 2000 and 2001 when the number of P. vivax malaria cases in DPRK reached the highest peak ever [13-15], which might have influenced the rapid increase of malaria cases in the northwestern part of ROK. In contrast to the malaria situation during the 1990s, few malaria cases occurred in the northeastern part of ROK. Besides the direct influence from DPRK, local transmission within ROK has been implicated in the more recent cases. Many cases occurred in Incheon and Goyang Cities that are more than 30 km away from the DMZ, and civilian cases, most of which generally reside south of the Civilian Control Line, have exceeded 60% of the total annual cases since 2003. Focal outbreaks have not been reported in Seoul or other areas that are not adjacent to the malaria-risk areas. All the cases diagnosed in Seoul or southern provinces involved persons who has lived or traveled in the malaria-risk areas.

Distribution of reported P. vivax malaria cases among ROK military personnel and civilians in malaria-risk areas during 1993-2007. Data and figures are from references [7-10]. (a) Administrative boundaries of the malaria-risk areas in ROK. DMZ represents the Demilitarized Zone. (b) Annual malaria cases among military personnel (left panels) and civilians (right panels). Large dots represent 100 cases, medium dots 10 cases, and small dots 1 case. The asterisk in the 1993 military personnel map represents the first case.

Copyright © The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 69, 159-167, 2003].

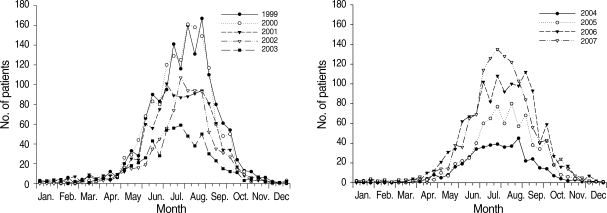

P. vivax malaria in ROK has presented a typical unstable malaria pattern (Fig. 3) [7-10]. Most malaria cases in civilians, who, in contrast to the military personnel, did not receive chemoprophylaxis, occurred from June through September with a unimodal peak. Ten-day incidence showed its peak in July and August. However, in 2005 and 2006, the incidence displayed a wider peak extending to early September, which was unusual considering the seasonal incidence pattern of the previous years [9,10]. The increase in P. vivax malaria cases during September and October in 2005 and 2006 means that early primary attack cases via short incubation period actively occurred, implying a longer transmission period during these years.

Number of P. vivax malaria cases of civilians, reported at 10-day intervals, 1999-2007, ROK. Data and figures are from references [7-10]. Copyright © The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 69, 159-167, 2003; 73, 604-608, 2005; 76, 865-868, 2007; 81, 605-610, 2009].

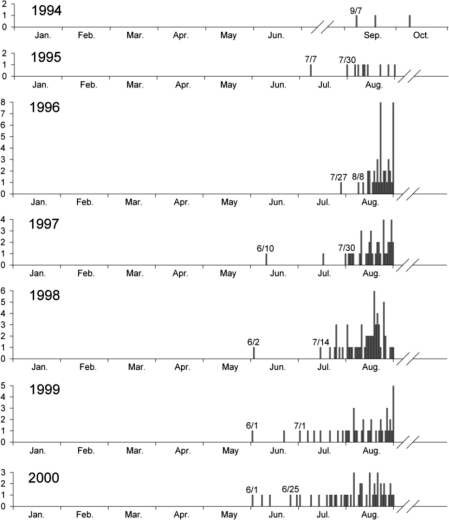

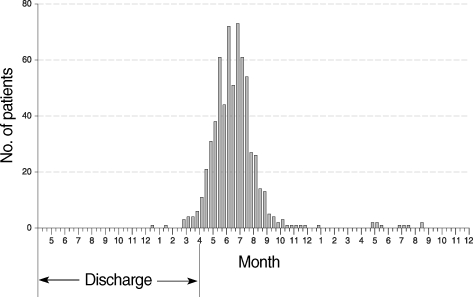

To determine the exact period of the first primary attack cases, P. vivax malaria cases with a short incubation period among ROK Army military patients who had been exposed to malaria for only 1 season, having begun their military service in the same year or after November of the previous year, were examined. The results showed that the first cases of early primary attack with a short incubation period occurred in early June (Fig. 4) [7]. These cases were attributed to mosquitoes that became infected from P. vivax malaria patients, who were exposed and transmitted in the previous year, in April of the current year. Therefore, the earliest cases would be transmitted from mosquitoes to humans in mid-May of the same year with symptoms being observed in early June. A large number of early primary attack cases began to occur from late July onwards. On the other hand, cases of the first late primary attack cases among veterans via a long incubation period mainly occurred during the first transmission season after their discharge, with the peak apparent between mid-June and mid-August (Fig. 5) [10]. This pattern was quite similar to that observed during the Korean War [4]. The basic biological characteristics of P. vivax with regard to relapse or late primary attack have remained the same for several decades on the Korean Peninsula.

Date of diagnosis for ROK military personnel without previous exposure to malaria the preceding year. The y-axis of each graph represents the number of patients. Data and figure are from reference [7].

Copyright © The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 69, 159-167, 2003].

Number of the first late primary attack cases of P. vivax malaria among veterans discharged from the military between May, 2003 and April, 2006, during 2 consecutive malaria-transmission seasons after their discharge. Data and figure are from reference [10].

Copyright © The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 81, 605-610, 2009].

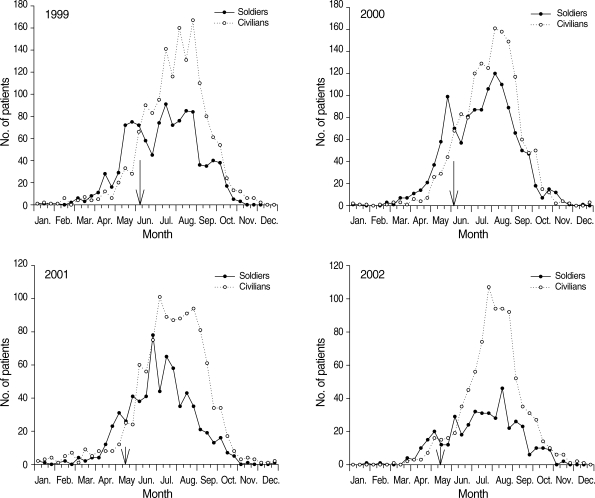

To cope with epidemic malaria among various military units and to reduce spread to civilian populations, chemoprophylaxis was initiated among military personnel assigned to areas deemed to be high-risk for malaria in 1997. Chemoprophylaxis has involved hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which is an analogue of chloroquine (CQ) with equivalent activity against malaria to CQ, followed by presumptive anti-relapse therapy with primaquine (PQ). The chemoprophylaxis program was expanded annually from approximately 16,000 soldiers in 1997 to 200,000 soldiers in 2005 (Table 2) [16]. Decreased incidence of P. vivax malaria in the ROK military was attributed to the annual expansion of chemoprophylaxis in high-risk malaria areas, especially since 1999. Prior to the initiation of chemoprophylaxis, soldier patients accounted for > 80% of all malaria cases in ROK (Table 3). With the introduction of chemoprophylaxis, the proportion of military cases out of the total annual cases declined to 67% in 1997 and to 24% in 2002. From 1999 through 2002, the prevalence of malaria in the military population began to decrease 1-2 weeks after the initiation of chemoprophylaxis in early June or mid-May. This finding was different that the steadily increasing cases of malaria cases among civilians not provided with chemoprophylaxis (Fig. 6). During the prophylactic period, the period from chemoprophylaxis was initiated to 1 week after the final dose of HCQ, the proportion of military personnel out of total annual cases was 71% (771/1,085) in 1999, 75% (960/1,288) in 2000, 82% (550/673) in 2001 and 80% (338/425) in 2002. On the other hand, the proportion of annual malaria cases among civilians during the prophylactic period was 87% (1,337/1,541) in 1999, 88% (1,333/1,515; in whom the day of symptom onset was confirmed) in 2000, 87% (963/1,111) in 2001 and 88% (760/866) in 2002 (Table 3) [16].

Proportion of the total ROK military cases and annual military malaria cases in areas of highest prevalence (Paju, Yeoncheon, and Cheolwon Counties) compared to the total number of annual malaria cases reported by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Ten-day incident cases of malaria involving soldiers and civilians in ROK, January 1999 through December 2002. Arrows represent the starting point of chemoprophylaxis in each year. Data and figures are from reference [16].

Copyright © The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences [Journal of Korean Medical Science, 20, 707-712, 2005].

Until 1997, > 90% of the total military cases occurred in areas of highest incidence including Yeoncheon, Paju, and Cheolwon Counties, where chemoprophylaxis was provided at the early stage. Cases in these regions gradually decreased to 56% by 2002 (Table 3) [16]. To calculate the chemoprophylactic efficacy, the occurrences of P. vivax malaria were compared between paired units with the similar risk for the exposure to infected Anopheline mosquitoes. In the treatment groups (those receiving chemoprophylaxis), a significant reduction in number of malaria cases was demonstrated while in their paired control group (no chemoprophylaxis) the number of cases increased significantly (Table 4) [16]. These results also demonstrate that even with partial chemoprophylaxis in malaria high-risk areas, the incidence of malaria decreased while expanding in adjacent counties where chemoprophylaxis was not provided.

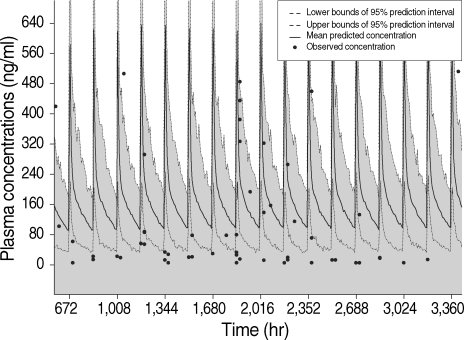

Mass chemoprophylaxis of United States soldiers was done on a large scale during the Korean War (1950-1953). However, the scale of chemoprophylaxis undertaken for ROK Army personnel since 1997 is unprecedented. Despite the sizable reduction in malaria incidence among military personnel as a result of this campaign, efficacy of the mass chemoprophylaxis has been hampered by poor compliance. Among soldier patients, < 25% followed a regular chemoprophylaxis schedule (Table 5) [10]. Mass chemoprophylaxis with poor compliance increases the possibility of the occurrence of CQ-resistant strains of P. vivax. Since 2000, many prophylactic failure cases had been reported in those soldiers who followed chemoprophylactic schedule. In some, plasma concentrations of HCQ were high enough to exert anti-malarial activity, which signifies resistance to the HCQ prophylactic regimen (Fig. 7) [17]. The steady reduction of malaria cases among military personnel suggests the necessity of a scale-down of chemoprophylaxis. Moreover, the elimination time of parasitemia by CQ or HCQ treatment has been prolonged and 2 cases of CQ-resistant P. vivax were confirmed in ROK (Table 6) [18]. These cases represented the first report of CQ-resistant P. vivax from a temperate region of Asia. In the patients, parasitemias were reduced markedly, but not cleared, by HCQ administration.

Compliance of military personnel patients to chemoprophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine and primaquine in ROK, 2005-2007

Comparison of the actual plasma concentrations of HCQ in 61 soldier patients infected with malaria parasites despite chemoprophylaxis for longer than 4 weeks to the simulated plasma time-concentration profiles of HCQ after oral administration of HCQ sulfate with a prophylactic dose of 400 mg/week. Data and figure are from reference [17].

Copyright © American Society for Microbiology [Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 53, 1468-1475, 2009]

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 2 patients infected with P. vivax who were unsuccessfully treated with the conventional HCQ regimen, ROK

Despite the epidemiological evidences linking DPRK to cases in ROK, DPRK was unwilling to confirm malaria occurrence in DPRK until 1998. However, it seems most likely that P. vivax malaria began to occur long before reemergence in ROK when considering various epidemiological data [19]. Official peak annual malaria incidence in DPRK was approximately 300,000 cases in 2001 (Fig. 8) [20]. This incidence might be an underestimate, since the official DPRK incidence has been confined to civilian cases, and most of the diagnosis has been made by clinical symptoms, not by microscopic confirmation.

Although the government of ROK had no irrefutable data on the DPRK malaria situation, it has donated materials and cash (> US$ 1 million annually since 2006) via the World Health Organization to DPRK since 2000 to help their malaria control activity [20]. This assistance by ROK has likely been influential in the decrease of P. vivax malaria incidence in DPRK after 2001, which subsequently influenced the situation in ROK. In the spring of 2007, a large-scale presumptive anti-relapse therapy with PQ was performed on approximately 5 million DPRK individuals involving ROK assistance. The rapid reduction in the case incidence during September and October of 2007 in ROK seems related to this activity (Fig. 3) [10]. In 2000 and 2001, the number of P. vivax malaria cases in DPRK reached the highest peak ever, with nationwide prevalence of the disease except in the northern mountainous areas (Table 7) [13,14,20]. After 2001, the total number of annual cases dropped, with the geographic distribution shrinking to the southwestern part of DPRK that harbor many rice fields [15]. Monthly incidence of P. vivax malaria in DPRK showed a similar pattern to that in ROK with the peak in August (Fig. 9) [20].

After reemergence in 1993, P. vivax malaria has been a constant presence in ROK. Even though the occurrence of malaria in ROK has been directly influenced by the malaria situation of DPRK, the possibility of local transmission within ROK has increased. Recently, the malaria transmission season became extended, possibly under the influence of global warming. CQ-susceptibility of P. vivax has steadily decreased; the 2 cases of CQ-resistant P. vivax, which were the first report of CQ-resistant P. vivax from a temperate region of Asia, were reported in ROK. Continuous surveillance and monitoring are warranted to prevent further expansion of CQ-resistant P. vivax in ROK.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Yuri Choi and Ms. Hye-Jin Kim for drawing the maps.We also thank Visiting Professor Seung-Yull Cho (Department of Parasitology, Graduate School of Medicine, Gachon University of Medicine and Science) for kindly reviewing this manuscript.