Cited By

Citations to this article as recorded by

Cryptosporidium spp. Diagnosis and Research in the 21st Century

Jennifer K. O'Leary, Roy D. Sleator, Brigid Lucey

Food and Waterborne Parasitology.2021; 24: e00131.

CrossRef Lateral Flow Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Test with Stem Primers: Detection ofCryptosporidiumSpecies in Kenyan Children Presenting with Diarrhea

Timothy S. Mamba, Cecilia K. Mbae, Johnson Kinyua, Erastus Mulinge, Gitonga Nkanata Mburugu, Zablon K. Njiru

Journal of Tropical Medicine.2018; 2018: 1.

CrossRef Causes of acute gastroenteritis in Korean children between 2004 and 2019

Eell Ryoo

Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics.2021; 64(6): 260.

CrossRef Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in Environmental Soil and Vegetables

Semie Hong, Kyungjin Kim, Sejoung Yoon, Woo-Yoon Park, Seobo Sim, Jae-Ran Yu

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2014; 29(10): 1367.

CrossRef Comparison of Three Real-Time PCR Assays Targeting the SSU rRNA Gene, the COWP Gene and the DnaJ-Like Protein Gene for the Diagnosis of Cryptosporidium spp. in Stool Samples

Felix Weinreich, Andreas Hahn, Kirsten Alexandra Eberhardt, Torsten Feldt, Fred Stephen Sarfo, Veronica Di Cristanziano, Hagen Frickmann, Ulrike Loderstädt

Expression and Purification of gp40/15 Antigen of Cryptosporidium parvum Parasite in Escherichia coli: an Innovative Approach in Vaccine Production

Hossein Sobati, Habib Jasor-Gharebagh, Hossein Honari

Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal.2017;[Epub]

CrossRef

Abstract

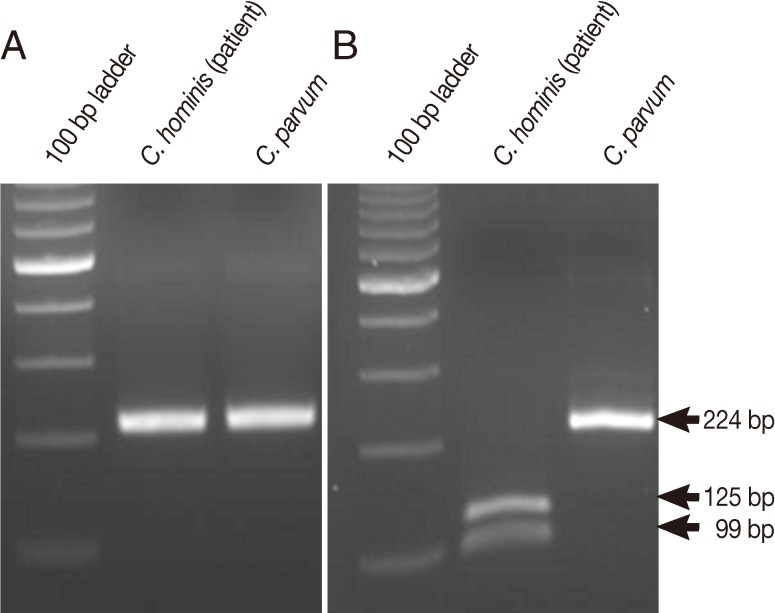

There are approximately 20 known species of the genus Cryptosporidium, and among these, 8 infect immunocompetent or immunocompromised humans. C. hominis and C. parvum most commonly infect humans. Differentiating between them is important for evaluating potential sources of infection. We report here the development of a simple and accurate real-time PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method to distinguish between C. parvum and C. hominis. Using the CP2 gene as the target, we found that both Cryptosporidium species yielded 224 bp products. In the subsequent RFLP method using TaqI, 2 bands (99 and 125 bp) specific to C. hominis were detected. Using this method, we detected C. hominis infection in 1 of 21 patients with diarrhea, suggesting that this method could facilitate the detection of C. hominis infections.

Key words: Cryptosporidium parvum, Cryptosporidium hominis, real-time PCR, RFLP, TaqI

Cryptosporidium parvum is a parasitic protozoan that infects gastrointestinal epithelial cells of many vertebrates, including humans [

1]. It causes watery diarrhea and can be fatal to immunocompromised individuals [

1]. There are 20 known

Cryptosporidium species and at least 44 genotypes, which differ significantly in their molecular signatures but have not been assigned species status [

2]. Eight fully characterized

Cryptosporidium species (

C. hominis,

C. parvum,

C. meleagridis,

C. felis,

C. canis,

C. suis,

C. muris, and

C. andersoni) and 5 partially characterized species (from the deer, monkey, skunk, rabbit, and chipmunk) infect humans [

2-

5], among which

C. hominis and

C. parvum are the most commonly detected [

3]. A real-time PCR (qPCR) method using primers derived from the

CP2 gene is highly sensitive, specific, and accurate for the detection of cryptosporidiosis but cannot distinguish among species [

6]. Therefore, we developed a qPCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method for the 2

Cryptosporidium spp. differentiation and we detected

C. hominis in 1 of 21 patients with diarrhea.

DNA was prepared from

C. parvum oocysts of (KKU isolates) collected from laboratory mice (C57BL6/J) that were infected with the parasite and maintained as described [

6]. DNA was extracted from the oocysts and fecal materials by using a QIA-quick Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Hamburg, Germany USA). The qPCR reactions were performed according to the method of Lee et al. [

6] using a LightCycler® (Roche, Basel, Switzerland, USA). The results were analyzed using the LightCycler® software (version 4.05, Roche). DNase/RNase-free water was used in place of template DNA as a negative control.

CP2 sequences of

C. parvum (AY471868) and

C. hominis (XM_661199) were aligned using Clone Manager Suite 7 (Sci-Ed Software, Cary, North Carolina, USA), and restriction enzyme cleavage sites were identified using NEBcutter V2.0 (

http://tools.neb.com/NEBcutter2/). An aliquot (15 µl) of the qPCR product was digested with

TaqI (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) at 65℃ for 2 hr, and DNA fragments were analyzed using 2.5% agarose gels. Stool samples from 21 patients with diarrhea in the Busan area of Korea were collected from June 1 to 30, 2011, by the Korea Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Modified acid-fast staining was performed on stool samples that were positive for

C. hominis by using qPCR-based RFLP.

The sequences of the

CP2 genes of

C. parvum (GenBank AY-471868) and

C. hominis (GenBank XM_661199) are 94% identical (data not shown). Because analysis using NEBcutter V2.0 identified a

TaqI site only in the sequence of

C. hominis

CP2 (

Table 1),

TaqI was chosen for restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis.

Using qPCR, we found that 1 of 21 patients with diarrhea tested was positive for

CP2 (data not shown). The patient with positive results was a 6-year-old girl with watery diarrhea. No other information about the patient was available. To further identify the species of

Cryptosporidium responsible for the infection, the sample was digested using

TaqI, which generated 99 bp and 125 bp bands, indicating that the patient was infected by

C. hominis (

Fig. 1).

C. hominis oocysts were also detected in the diarrheal stool sample by using the modified acid-fast staining (

Fig. 2).

Morgan-Ryan et al. [

7] proposed a new species of

Cryptosporidium,

C. hominis, to indicate its isolation from human feces. However,

C. hominis and

C. parvum oocysts are morphologically indistinguishable [

7]. Species discrimination is important for molecular epidemiological purposes to evaluate potential sources of infections [

8]. Real-time PCR increases the speed of sample analysis and decreases the risks of contamination with DNA present in the laboratory [

8]. The present study showed that both major

Cryptosporidium species can be detected simultaneously and distinguished from each other by using

TaqI to digest the

CP2 gene of

C. hominis. Because the

CP2 gene is highly specific, no genetic information is available for other

Cryptosporidium species, except for

C. parvum and

C. hominis in GenBank (

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

The genotypes of

Cryptosporidium in Korea have been reported [

9-

11]. Cheun et al. [

11] studied

Cryptosporidium sp. in 3 rural areas by using a PCR-RFLP method to detect 18S rDNA sequences and identified

C. parvum in 12 patients with

Cryptosporidium infection. Therefore, the case confirmed by the present study is very important, because it indicates the presence of

C. hominis infection in Korea.

In the present study, we developed a simple and accurate qPCR-based RFLP method for differentiating C. parvum from C. hominis. This method could be helpful in facilitating the detection of C. hominis infection in Korea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (RF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2011-3333702) and by a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH-2010E5401000), Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Republic of Korea. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. O'Donoghue PJ.

Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis in man and animals.

Int J Parasitol 1995;25:139-195.

2. Xiao L, Fayer R, Ryan U, Upton SJ. Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:72-97.

3. Caccio SM, Thompson RC, McLauchlin J, Smith HV. Unravelling

Cryptosporidium and Giardia epidemiology.

Trends Parasitol 2005;21:430-437.

4. Nichols RA, Campbell BM, Smith HV. Molecular fingerprinting of

Cryptosporidium oocysts isolated during water monitoring.

Appl Environ Microbiol 2006;72:5428-5435.

5. Feltus DC, Giddings CW, Schneck BL, Monson T, Warshauer D, McEvoy JM. Evidence supporting zoonotic transmission of

Cryptosporidium spp. in Wisconsin.

J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4303-4308.

6. Lee SU, Joung M, Ahn MH, Huh S, Song H, Park WY, Yu JR. CP2 gene as a useful viability marker for

Cryptosporidium parvum.

Parasitol Res 2008;102:381-387.

7. Morgan-Ryan UM, Fall A, Ward LA, Hijjawi N, Sulaiman I, Fayer R, Thompson RC, Olson M, Lal A, Xiao L.

Cryptosporidium hominis n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) from Homo sapiens.

J Eukaryot Microbiol 2002;49:433-440.

8. Jothikumar N, da Silva AJ, Moura I, Qvarnstrom Y, Hill VR. Detection and differentiation of

Cryptosporidium hominis and

Cryptosporidium parvum by dual TaqMan assays.

J Med Microbiol 2008;57:1099-1105.

9. Guk SM, Yong TS, Park SJ, Park JH, Chai JY. Genotype and animal infectivity of a human isolate of

Cryptosporidium parvum in the Republic of Korea.

Korean J Parasitol 2004;42:85-89.

10. Park JH, Guk SM, Han ET, Shin EH, Kim JL, Chai JY. Genotype analysis of

Cryptosporidium spp. prevalent in a rural village in Hwasun-gun, Republic of Korea.

Korean J Parasitol 2006;44:27-33.

11. Cheun HI, Choi TK, Chung GT, Cho SH, Lee YH, Kimata I, Kim TS. Genotypic characterization of

Cryptosporidium oocysts isolated from healthy people in three different counties of Korea.

J Vet Med Sci 2007;69:1099-1101.