Abstract

Myiasis is usually caused by flies of the Calliphoridae family, and Cochliomyia hominivorax is the etiological agent most frequently found in myiasis. The first case of myiasis in a diabetic foot of a 54-year-old male patient in Argentina is reported. The patient attended the hospital of the capital city of Tucumán Province for a consultation concerning an ulcer in his right foot, where the larval specimens were found. The identification of the immature larvae was based on their morphological characters, such as the cylindrical, segmented, white yellow-coloured body and tracheas with strong pigmentation. The larvae were removed, and the patient was treated with antibiotics. The larvae were reared until the adults were obtained. The adults were identified by the setose basal vein in the upper surface of the wing, denuded lower surface of the wing, short and reduced palps, and parafrontalia with black hairs outside the front row of setae. The main factor that favoured the development of myiasis is due to diabetes, which caused a loss of sensibility in the limb that resulted in late consultation. Moreover, the poor personal hygiene attracted the flies, and the foul-smelling discharge from the wound favoured the female's oviposition. There is a need to implement a program for prevention of myiasis, in which the population is made aware not only of the importance of good personal hygiene and home sanitation but also of the degree of implication of flies in the occurrence and development of this disease.

-

Key words: Cochliomyia hominivorax, myiasis, diabetic foot ulcer, Argentina

INTRODUCTION

Myiasis is the infestation of a vertebrate with dipterous larvae that feed for a certain time period on live or dead tissues of the host, substances of the host's body, or on the food that it ingests [

1]. Myiasis can be obligatory, which occurs when larval flies develop in living tissues, or facultative, which occurs when maggots feed on decomposing matter or necrotic tissues. Obligatory myiasis is more harmful to the host, particularly mammals (including man), and is found in several countries of the Old and New Worlds [

2,

3]. The classification of myiasis is based on the localization within the host body (dermal, subdermal, nasopharyngeal, internal organs, or urogenital) or the type of host-parasite relationships (obligatory, facultative, or pseudomyiasis) [

3]. The larvae that cause myiasis can be biontophagous, in which they invade tissues or natural cavities to become obligate parasites, or necrobiontophagous, in which larvae colonise pre-existing injuries and become accidental parasites [

4].

Numerous species have been reported to be responsible for myiasis in livestock and occasionally in humans. One of these species,

Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel), is well-known to be responsible for important myiasis along its wide distribution in America and in relation to the tropical climate zones [

5]. Although adult flies may be attracted to wounds or ulcers on the skin of the host, their larvae do not feed on necrotic material. The invasion of natural orifices by larvae may result in cavitary myiasis of several types, which culminates in major tissue damage or even death of the host [

6,

7]. The analysis of the life cycle of the species has shown that females lay 200-300 eggs on wound borders, larvae eclosion occurs within 12-14 hr, and the larvae penetrate the tissues as they feed on them. The infected wounds release a smell that stimulates gravid flies to oviposit their eggs [

8].

The risk factors that potentially cause myiasis are the exposure of ulcers and hemorrhoids, bacterial infection of wounds or natural cavities, poor personal hygiene, alcohol-related behaviors such as lack of sensitivity and sleeping outdoors, lesions resulting from itching in patients with pediculosis, and extreme lack of personal hygiene [

9].

In this work, we provided the first demonstration of the presence of myiasis in a diabetic foot in Argentina with C. hominivorax as an etiological agent. This study also provides the first evidence of this species in Tucuman Province, Argentina.

CASE DESCRIPTION

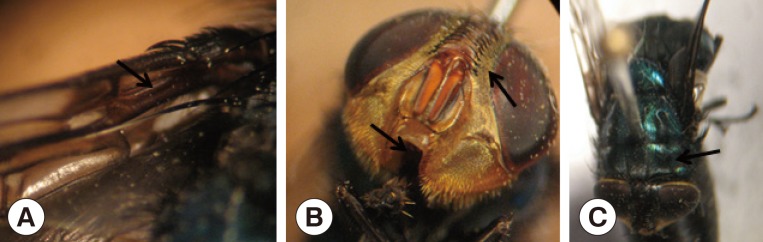

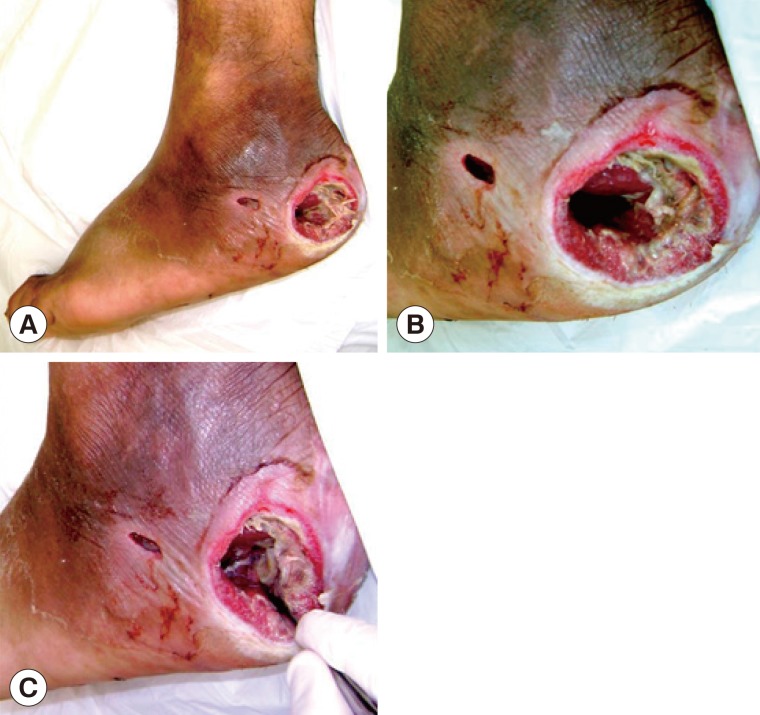

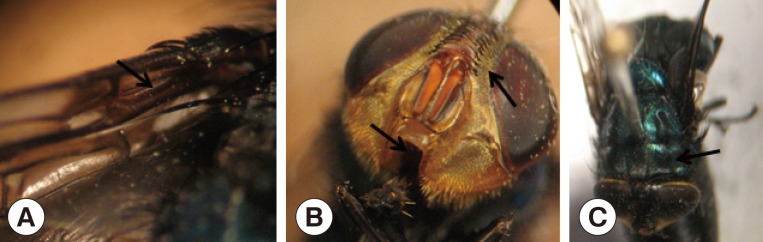

A male patient aged 54 years, who is now living in Monteros City, Tucuman Province, Argentina, checked into the Angel C. Padilla Hospital in San Miguel de Tucuman for a consultation due to an ulcerous lesion in his right foot with a sanious bottom and fetid odour (

Fig. 1A). The clinical examination revealed that the ulcer contained fly larvae (n=5) with an evolution of approximately 2 days.

The lesion had a circular shape with a diameter of approximately 4 cm; the edge showed signs of inflammation, and the content consisted of foul-smelling necrotic tissues with a sanious bottom that corresponded to the deep aponeurosis of the wound (

Fig. 1B).

The patient was diagnosed with grade II diabetes (under treatment with oral hypoglycemic drugs) with a disease of over 10 years of evolution, in which the neuropathic compromise predominated with an important loss of sensibility in the area (no pain), which was the reason for delayed consultation. However, the presence of peripheral pulses was determined, which indicates that the blood flow in the compromised limb was preserved. The first surgical debridement was performed in the hospital emergency services unit. During this operation, the larvae were mechanically extracted using a sulphuric ether solution (

Fig. 1C). Tissue samples were extracted for culturing, germ identification, and antibiogram tests.

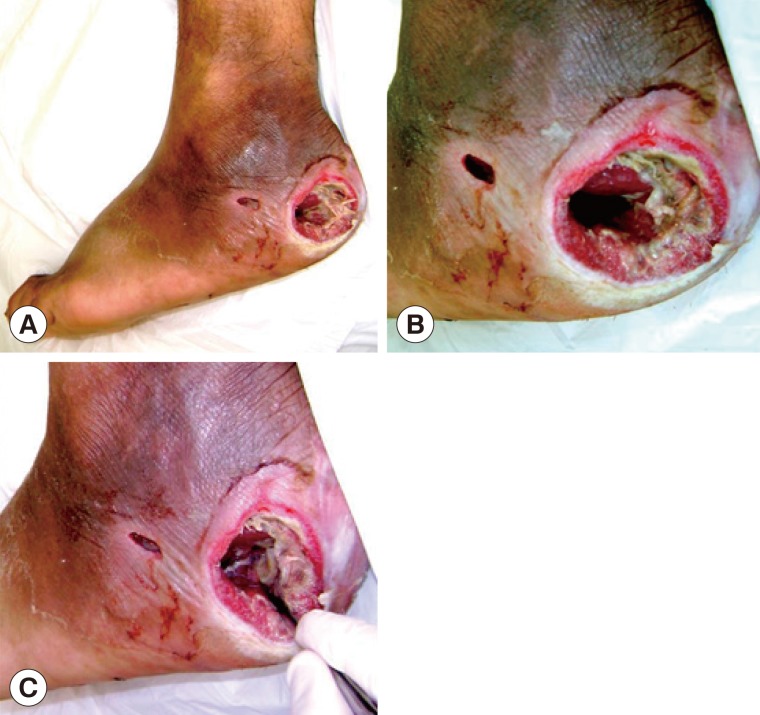

The patient received treatment considering his basic disease (diabetes) with broad-spectrum antibiotics until the results of the cultures were obtained. Additionally, periodic cleaning of the wound and dressing changes were conducted every other day with gauze wetted in a physiological solution. The wound, as well as the patient's metabolic values, exhibited a favourable evolution. He was discharged from the hospital after 15 days, during which time surgical debridement was performed twice. The larval specimens were taken to the laboratory of the Instituto Superior de Entomologia "Dr. Abraham Willink", Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo (Universidad Nacional de Tucuman), where they were identified and later raised individually in flasks and fed beef liver (

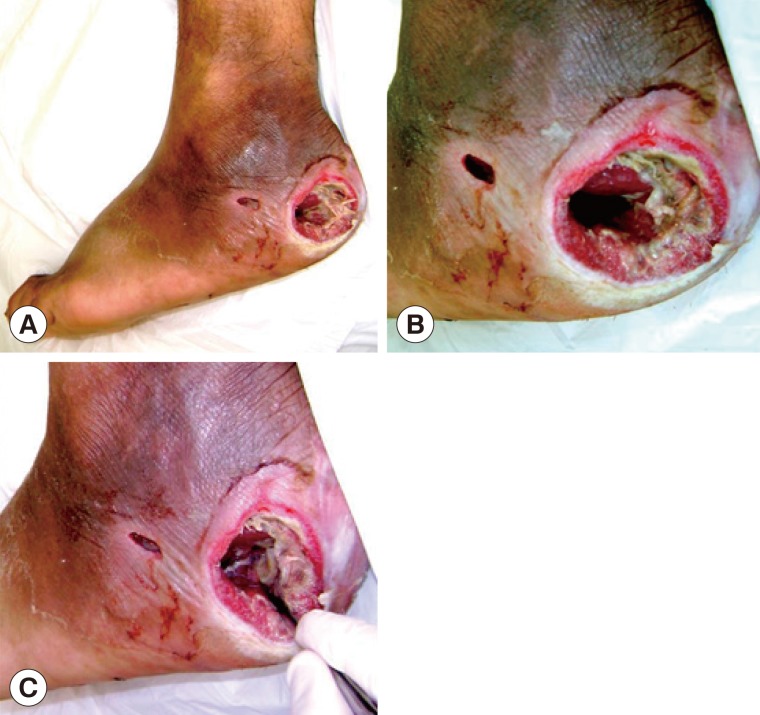

Fig. 2).

The collected larvae belong to the species

C. hominivorax with the following external morphological characters: cylindri cal, segmented, white yellow-coloured body, and tracheas with strong pigmentation that was visible until the third or fourth larval segment immediately preceding the end portion of the body [

10].

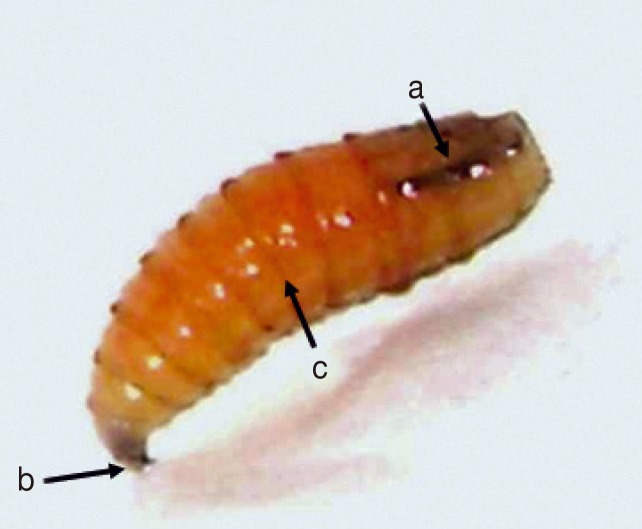

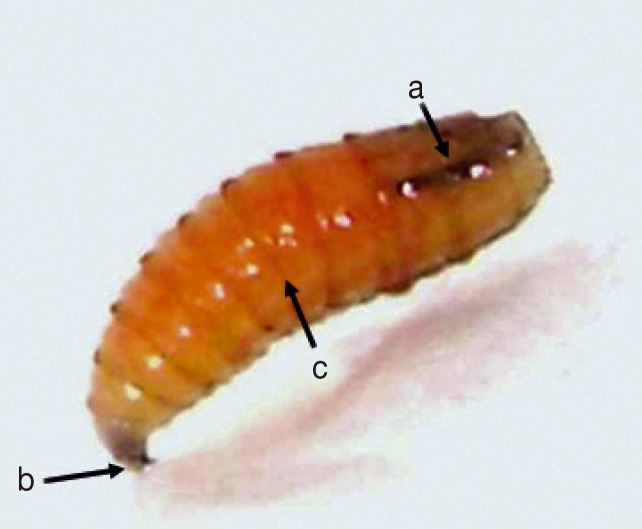

After 2 days, the larvae reached the pupal stage and were transferred to plastic cups containing vermiculite. The cups were covered with mosquito netting. The humidity was controlled by spraying water, and the temperature was maintained at 27℃. After 12 days, the adult insects emerged. The adults were then killed, mounted, and identified using the guidelines described by Mariluis and Schnack [

11]. The adults were also identified as

C. hominivorax, which is a species that had not been previously reported in Tucuman Province, Argentina [

12]. The morphological characters that defined the adult species were as follows: setose basal vein in the upper surface of the wing, denuded lower surface of the wing, short and reduced palps, and parafrontalia with black hairs outside the front row of setae (

Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The species of the genus

Cochliomyia present a wide geographical distribution from the central and southern United States through Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean islands to Argentina [

5]. In our country, only 2 species belonging to this genus have been reported:

Cochliomyia macellaria (Fabricius) and

C. hominivorax. The latter is distributed in the provinces of Buenos Aires, Chaco, Córdoba, Corrientes, Formosa, Jujuy, Santa Fe, and Misiones [

12]. The present work is the first report of the species in Tucuman Province, which is extremely important because

C. hominivorax is potentially involved in production of myiasis in humans.

C. hominivorax is an obligate parasite in homeothermic vertebrates, either domestic or wild, occasionally including humans. It is considered that a fly has great impact on human health and on the productivity of domestic animals because it causes a decrease in their productions of meat, milk, and wool and an increase in secondary infections [

13]. In addition,

C. hominivorax is responsible for the largest number of myiasis cases in America and the most serious forms of human myiasis [

14]. The larvae remain superficial but occasionally migrate and cause subcutaneous nodules [

15]. In general, myiasis in humans is localized in the upper and lower extremities with a marked predominance of the latter followed in frequency by the head, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis. Moreover, underlying pathologies have been found: varicose ulcers, infected wounds, and various dermatoses [

16].

Visciarelli et al. [

17] have cited the species incriminated in human myiasis,

C. hominivorax and

Phaenicia sericata (also called

Lucilia sericata) (Meigen), to Bahia Blanca, Buenos Aires, Argentina. In all patients, myiasis occurred after traumas, lesions, and/or infectious processes that attracted the flies.

C. hominivorax was the species most common found in the cases of myiasis and was responsible for serious lesions in the abdomen, the lower limbs, and different parts of the head (ears and eyelids).

P. sericata was found in lesions of the lower limbs. Among other conditioning factors for the occurrence of myiasis, the insensibility that may result from various pathologies, such as diabetes, is mentioned in this work and added to the poor personal hygiene conditions.

Exposed ulcers, bacterial infections of wounds or natural cavities [

18-

20], poor personal hygiene [

21], tasks related to livestock rearing [

22,

23], and behaviors associated with alcoholism, such as insensibility and sleeping outdoors [

24], are among the risk factors that promote myiasis.

Visciarelli et al. [

17] also mentioned different pathologies, such as diabetes, otitis, and alcoholism, and certain behaviors, such as lack of body hygiene, lack of personal grooming, and/or rural tasks, that favour the permanence of the wounds by causing insensibility and increasing the probability of contact with flies. In the present work, we agree with the hypothesis that the exposed ulcer was a conditioning factor that, in combination with the patient's poor personal hygiene, rural tasks and insensibility associated with diabetes determined the degree of evolution of the myiasis in the patient.

We may conclude that the present investigation is an important contribution to the subject of myiasis because this case is the first evidence of C. hominivorax in a case of myiasis in a patient with a diabetic foot in Argentina. The main factor that would determine the occurrence of this myiasis would be the exposure of the ulcer to flies, foul smell of the wound, individual's lack of personal grooming, and diabetes which was responsible for the consequent loss of sensibility in the patient's foot.

Notes

-

We have no conflict of interest related with this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank the staff of the emergency service unit of the Ángel C. Padilla Hospital at San Miguel de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina for supplying the larval specimens.

References

- 1. Zumpt F. Myiasis in man and animals in the Old World. London, UK. Butterworths; 1965, p 267.

- 2. Hall MJR, Wall R. Myiasis of humans and domestic animals. Adv Parasitol 1995;35:257-334.

- 3. Gomez RS, Perdigão PF, Pimenta FJGS, Rios Leite AC, Tanos de Lacerda JC, Custódio Neto AL. Oral myiasis by screwworm Cochliomyia hominivorax. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;41:115-116.

- 4. Visciarelli EC, Garcia SH, Salomón C, Jofre C, Costamagna SR. Un caso de miasis humana por Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae) asociado a pediculosis en Mendoza, Argentina. Parasitol Latinoam 2003;58:166-168.

- 5. James MT. The flies that cause myiasis in man. US Department of Agriculture. Misc Publ 1974;631:1-175.

- 6. Guimarães JH, Tucci EC, Barros-Battesti DM. Ectoparasitas de importância veterinária Plêiade. São Paulo, Brazil. Plêiade; 2001, pp 105-154.

- 7. Thyssen PJ, Prado Nassu M, Uratani Costella AM, Lopes Costella M. Record of oral myiasis by Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae): case evidencing negligence in the treatment of incapable. Parasitol Res 2012;111:957-959.

- 8. Rossi CG, Mariluis CJ, Schanck AJ, Spinelli GR. Dípteros vectores (Culicidae y Calliphoridae) de la provincia de Buenos Aires. ProBiota 2002;3:1-45.

- 9. Velasco E, Ramírez E, Cortizas A. Myiasis. Anal Pren Med Argent 1974;61:775.

- 10. Hall DG. The blowflies of North America. Lafayette, Indiana, USA. Thomas Say Foundation, Entomological Society of America; 1948, p 477.

- 11. Mariluis JC, Schnack JA. Calliphoridae de la Argentina. Stemática, ecología e importancia sanitaria (Diptera, Insecta). In Salomón OS ed, Actualizaciones en Artropodología Sanitaria Argentina. Buenos Aires. Fundación Mundo Sano; 2002, pp 23-37.

- 12. Mariluis CJ, Mulieri RP. Distribución de Calliphoridae (Diptera) en Argentina. Rev Soc Entomol Argent 2003;62:85-97.

- 13. Forero EB, Cortés JV, Villamil LJ. Problemática de gusano barrenador del ganado, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858) en Colombia. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2008;13:1400-1414.

- 14. Acha PN, Szyfres B. Zoonosis y enfermedades transmisibles comunes al hombre y a los animales. Parte V. Sección C: Artrópodos. Myiasis. 2ª ed. O. P. S; 1992, pp 886-889.

- 15. Botero D, Restrepo M. Parasitosis Humana. Enfermedades causadas por artrópodos. 3ª ed. Medellín, Colombia. C. I. B; 1998, pp 402-405.

- 16. Mariluis JC, Schanck JA. Importancia sanitaria de los dípteros califóridos. Ser Acad Nac Agr Vet 1996;20:59-65.

- 17. Visciarelli E, Costamagna S, Lucchi L, Basabe N. Miasis Humana en Bahía Blanca, Argentina: periodo 2000/2005. Neotrop Entomol 2007;36:605-611.

- 18. Mazza S, Basso R. Miasis de úlcera crónica de pierna por Sarcophaga barbata y Cochliomyia hominivorax. Investigaciones sobre dípteros argentinos,. Misión de Estudios de Patología Regional (M. E. P. R. A) 1939;41:47-54.

- 19. Mönning H. Veterinary helminthology and entomology. The diseases of domesticated animals caused by helminth and arthropod parasites. London, UK. Baillère, Tindall & Cox ed; 1949, p 427.

- 20. Calderón O, Rivera P, Sánchez C, Solano M. Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae) como agente causal de miasis aural en un nino de Costa Rica. Parasitol Día 1996;20:130-132.

- 21. Jörg M. Miasis anal y consideraciones generales del parasitismo por larvas de mosca. Pren Med Argent 1976;63:47-51.

- 22. Bacigalupo J, Villamil C. Miasis humana por Oestrus ovis Linneo 1761. Primeras Jornadas de Entomoepidemiol Arg 1959;2:833-836.

- 23. Jörg M. Conjuntivitis aguda por larvas de Oestrus ovis, Linneo, 1761. Dos observaciones en la Argentina. Pren Med Argent 1973;60:1155-1159.

- 24. Basso R. Frecuencia y naturaleza de las miasis en Mendoza. Observación n° 7 y n° 10. Investigaciones sobre dípteros argentinos. Misión de Estudios de Patología Regional Argentina(M.E.P.R.A) 1939;41:61-65.

Fig. 1Diabetic foot ulcer region. (A) Clinical appearance of the ulcer in the heel of the right foot with the larvae inside it. (B) Cavitary lesion/ulcer caused by the larvae of Cochliomyia hominivorax. Note that the circular border is swollen and necrotic tissues are observed inside. (C) Mechanical extraction of the C. hominivorax larvae.

Fig. 2Third-instar larvae of Cochliomyia Hominivorax. (a) Darkly pigmented dorsal tracheal trunk in posterior segments. (b) Mouth parts. (c) Bands of spines.

Fig. 3 Adult of Cochliomyia hominivorax. (A) Setose basal vein in the upper surface of the wing and denuded lower surface of the wing. (B) Short and reduced palps and parafrontalia with black hairs outside the front row of setae. (C) Three dark longitudinal stripes on the thorax.