Abstract

Knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) of mosquitoes confer resistance to insecticides. Although insecticide resistance has been suspected to be widespread in the natural population of Aedes aegypti in Myanmar, only limited information is currently available. The overall prevalence and distribution of kdr mutations was analyzed in Ae. aegypti from Mandalay areas, Myanmar. Sequence analysis of the VGSC in Ae. aegypti from Myanmar revealed amino acid mutations at 13 and 11 positions in domains II and III of VGSC, respectively. High frequencies of S989P (68.6%), V1016G (73.5%), and F1534C (40.1%) were found in domains II and III. T1520I was also found, but the frequency was low (8.1%). The frequency of S989P/V1016G was high (55.0%), and the frequencies of V1016G/F1534C and S989P/V1016G/F1534C were also high at 30.1% and 23.5%, respectively. Novel mutations in domain II (L963Q, M976I, V977A, M994T, L995F, V996M/A, D998N, V999A, N1013D, and F1020S) and domain III (K1514R, Y1523H, V1529A, F1534L, F1537S, V1546A, F1551S, G1581D, and K1584R) were also identified. These results collectively suggest that high frequencies of kdr mutations were identified in Myanmar Ae. aegypti, indicating a high level of insecticide resistance.

-

Key words: Aedes aegypti, knockdown resistance, voltage-gated sodium channel, Myanmar

Rapid urbinization, climate change and increasing global trade enhance the widespread incidence of mosquito-borne diseases worldwide [

1,

2]. Insecticide usage and environmental sanitation are the most common methods used to control mosquitoes due to their effectiveness, feasibility and economic viability [

3]. Mosquitoes have been relatively well controlled by insecticides; however, concerns that indiscreet and long-term usage of insecticides induces the development or emergence of insecticide resistance, which eventually reduces the effectiveness of currently used insecticides and threatens global mosquito control programs, have been increasing [

4,

5]. Until now, 4 different mechanisms of insecticide resistance have been recognized: (1) increased production of metabolic detoxification enzymes, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, esterases, and glutathione S-transferases, (2) mutations in target genes such as voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC), gamma-amino butyric acid receptor (GABA), and acetylcholine esterases, (3) decreased insecticide penetration due to cuticle thickening, and (4) altered mosquito behaviors [

6,

7]. Pyrethroid insecticides are regarded as one of the most promising measures for mosquito control due to their fast-acting and effective insecticidal activities and low toxicity to mammals, including humans [

8,

9]. They interfere with the normal nerve function of insects by disrupting the VGSC function and by depolarizing neurons that leads to paralysis and death [

10,

11]. However, repeated and indiscreet application of insecticides induces knockdown resistance (

kdr) in the VGSC that confers insecticide resistance. Structural changes of the VGSC by these mutations reduces the binding affinity of pyrethroid insecticides to its target site and results in poor sensitivity to the insecticides [

4,

5,

12,

13]. More than 50

kdr mutations associated with resistance to pyrethroids have been identified in various arthropod pests and vectors, including mosquitoes [

9,

14].

Aedes aegypti is the primary vector of arbovirus, including dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya fever, and Zika viruses in many geographical locations [

15–

18].

Aedes aegypti is a primary vector of dengue fever in Myanmar. Warm and humid climate and unsanitary environmental condition that are favorable for the proliferation of

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes contributes to the spread of

Ae. aegypti in the country [

19,

20]. An estimated population of 3.9 billion is at risk of dengue fever worldwide [

21] and more than 20,000 annual cases have been reported in the last decade in Myanmar [

22–

25]. Pyrethroid insecticides represent the primary control measure for

Ae. aegypti in Myanmar; however, the massive use of insecticides to control mosquitoes has increased concerns of insecticide resistance. Therefore, an understanding of the status of insecticide resistance is important to develop guidelines and alternative methods for mosquito control in Myanmar. In this study, the overall prevalence and distribution of

kdr mutations in the VGSC of the

Ae. aegypti in the Mandalay region, Myanmar, were investigated.

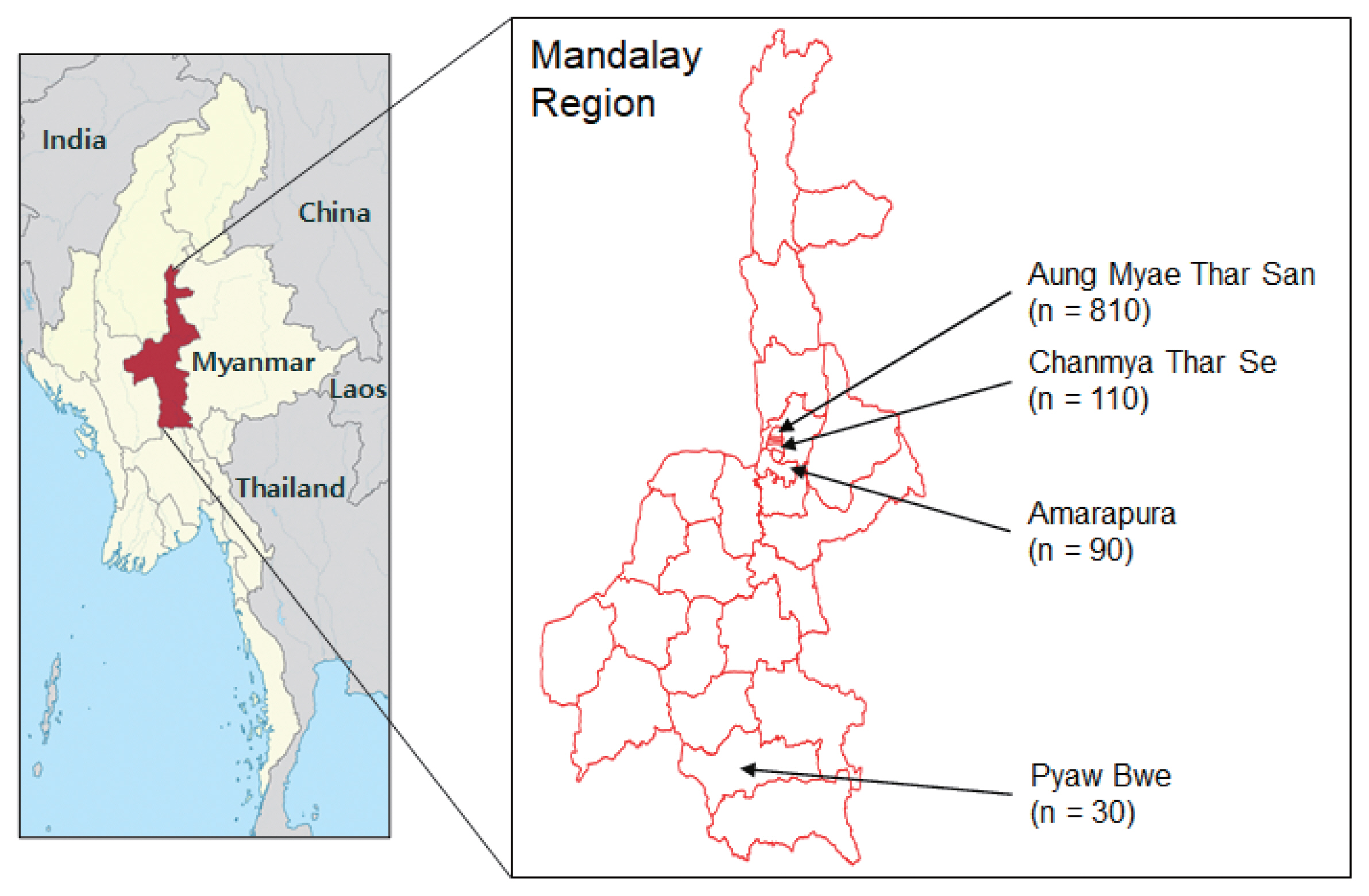

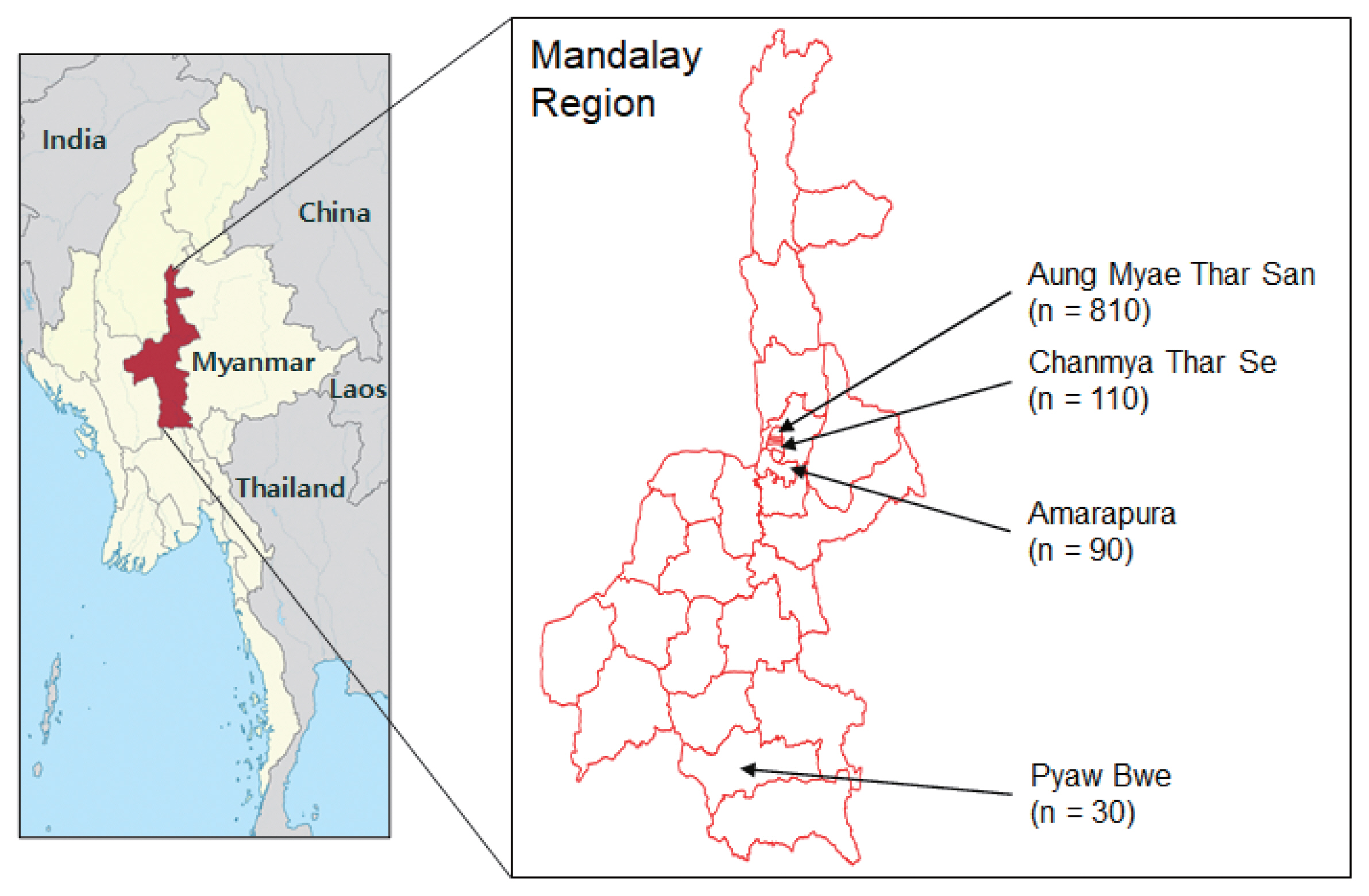

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were collected in 4 townships, Aung Myae Thar San (21°59′32.9″N 96°06′51.9″E), Chanmya Thar Se (21°56′55.5″N 96°06′33.6″E), Amarapura (21°54′56.1″N 96°03′39.3″E), and Pyaw Bwe (20°35′27.2″N 96°02′53.1″E), of Mandalay region, Myanmar from December 2016 to March 2017 (

Fig. 1). Mosquito larvae and pupae were collected from different habitants in and around human dwellings. Different types of mosquito breeding sites, such as metal drums, traditional clay pots for water storage, concrete water storage tanks, discarded tires, plastic cups and artificial water containners, were the main source of collections. The collected larvae and pupae were reared to adult in the laboratory insectary at 25±2°C and humidity of 80±10%. Adult mosquitoes were identified using standard mosquito identification keys under microscopy [

26].

A total of 1,040

Ae. aegypti adult mosquitoes were obtained and placed in 103 pools of up to 10 mosquitoes based on collection sites and regions. The mosquitoes were transferred to 1.5 ml sterile tubes and stored at −80°C until use. Genomic DNA was extracted from the pooled mosquitoes using the Tissue DNA extraction kit (Bioneer, Daejon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Segment 6 region flanking domains II and III of the

VGSC in

Ae. aegypti were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers described previously [

14]. The thermal cycling conditions were; initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 56°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 30 sec, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gel, purified from gel, and ligated into the T&A vector (Real Biotech Corporation, Banqiao City, Taiwan). Each ligation mixture was transformed into

Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells (Real Biotech Corporation) and positive clones with appropriate insert were selected via colony PCR. The nucleotide sequences of the cloned inserts were analyzed by automatic DNA sequencing (Genotech, Daejeon, Korea). Plasmids from at least 2 or 3 independent clones from each mosquito sample were sequenced bi-directionally to verify sequence accuracy.

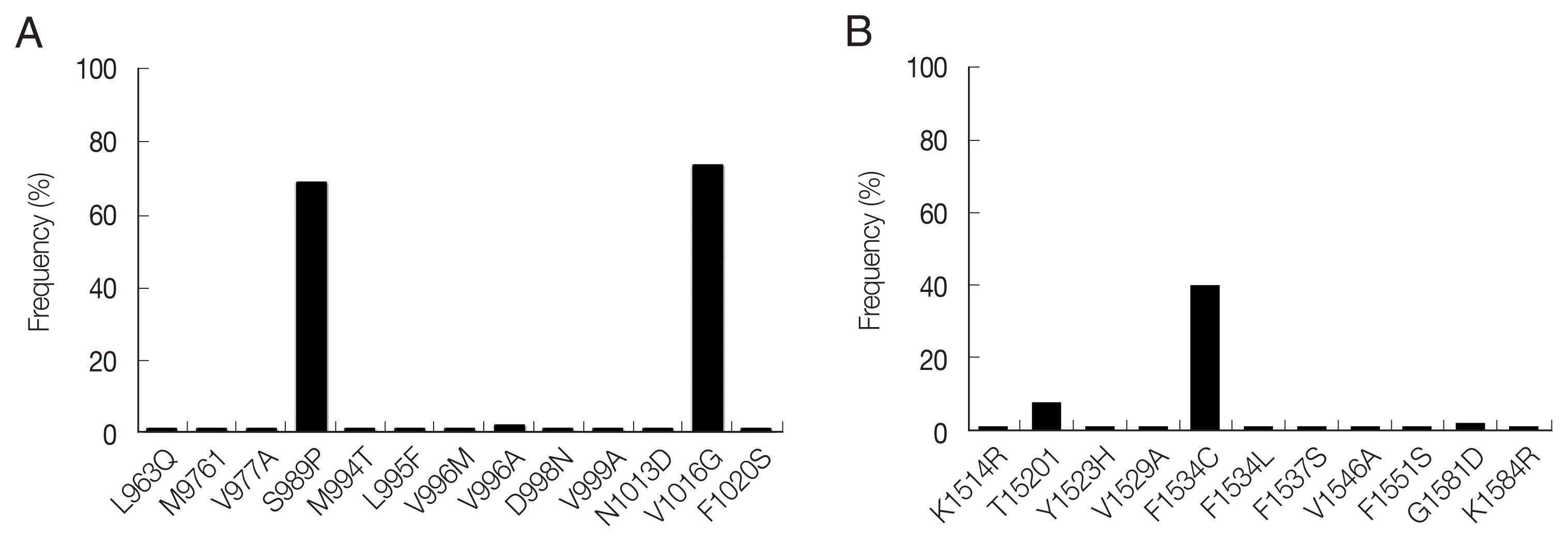

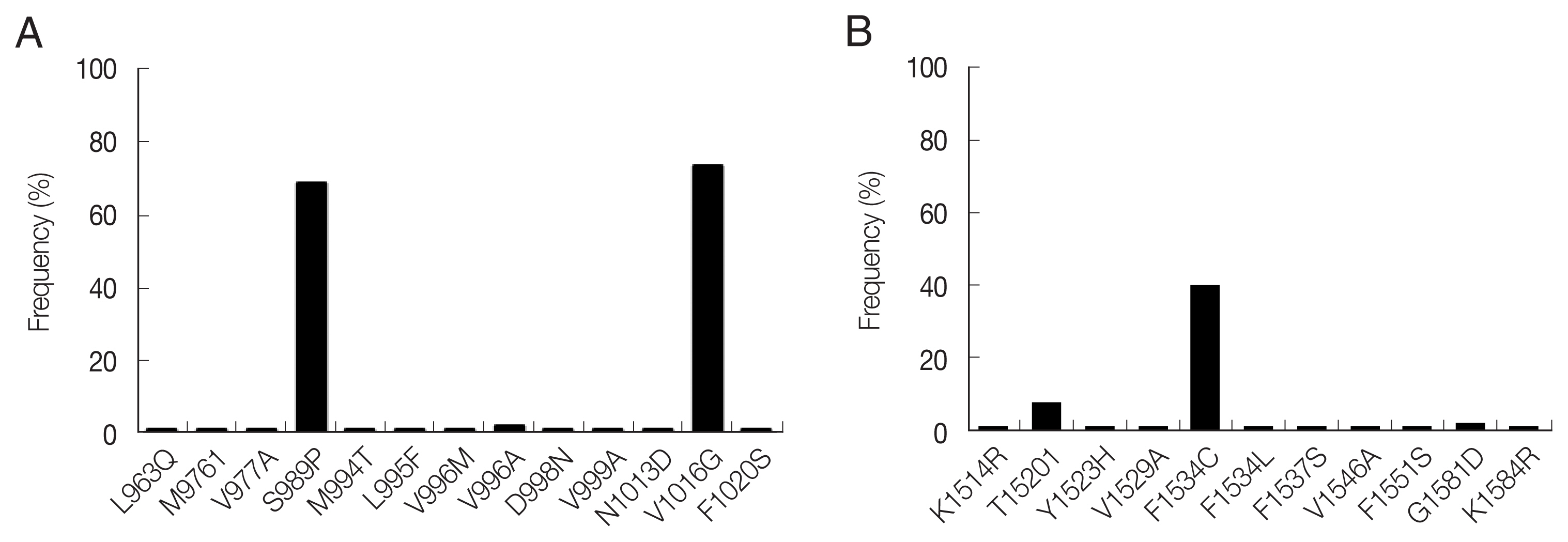

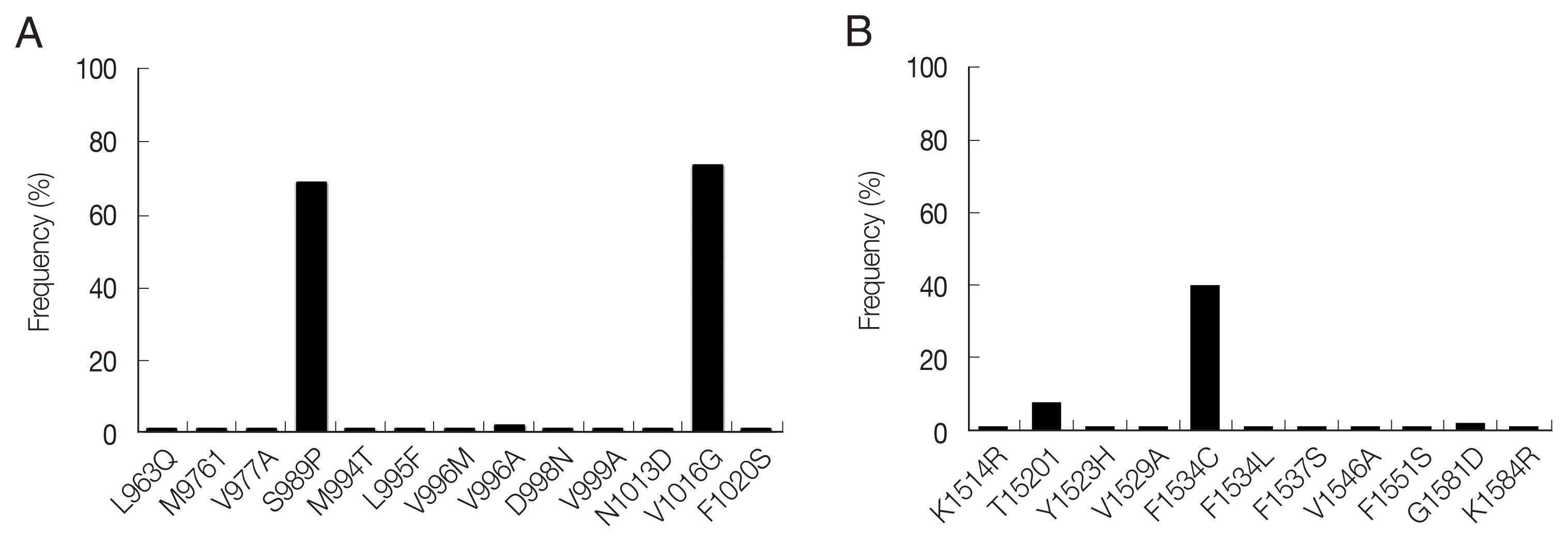

A total of 13 mutations resulting in amino acid changes were dectected at 12 positions in domain II (

Fig. 2A). S989P and V1016G were highly prevalent with frequencies of 68.6% and 73.5%, respectively. The other 11 mutations (L963Q, M976I, V977A, M994T, L995F, V996M/A, D998N, V999A, N1013D and F1020S) were also detected, but with low frequencies ranging from 1.0% to 2.0%. These 11 mutations were novel in that they have not been reported previously in

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes globally. A total of 11 amino acid mutations were detected at 10 positions in domain III (

Fig. 2B). F1534C showed the highest frequency of 40.1%, followed by T1520I (8.1%). Nine novel mutations (K1514R, Y1523H, V1529A, F1534L, F1537S, V1546A, F1551S, G1581D and K1584R) were detected with low frequencies (1.0–2.0%).

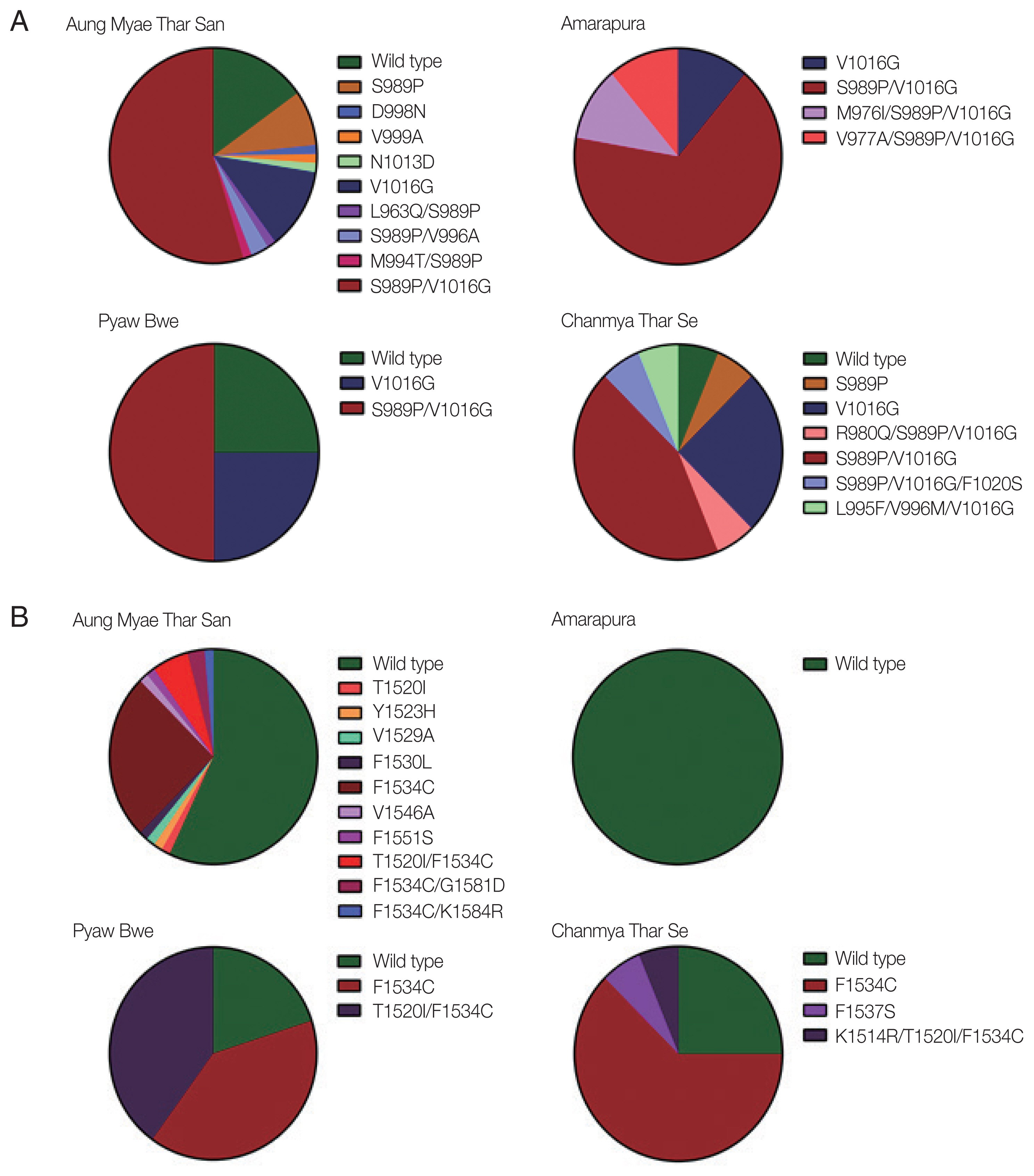

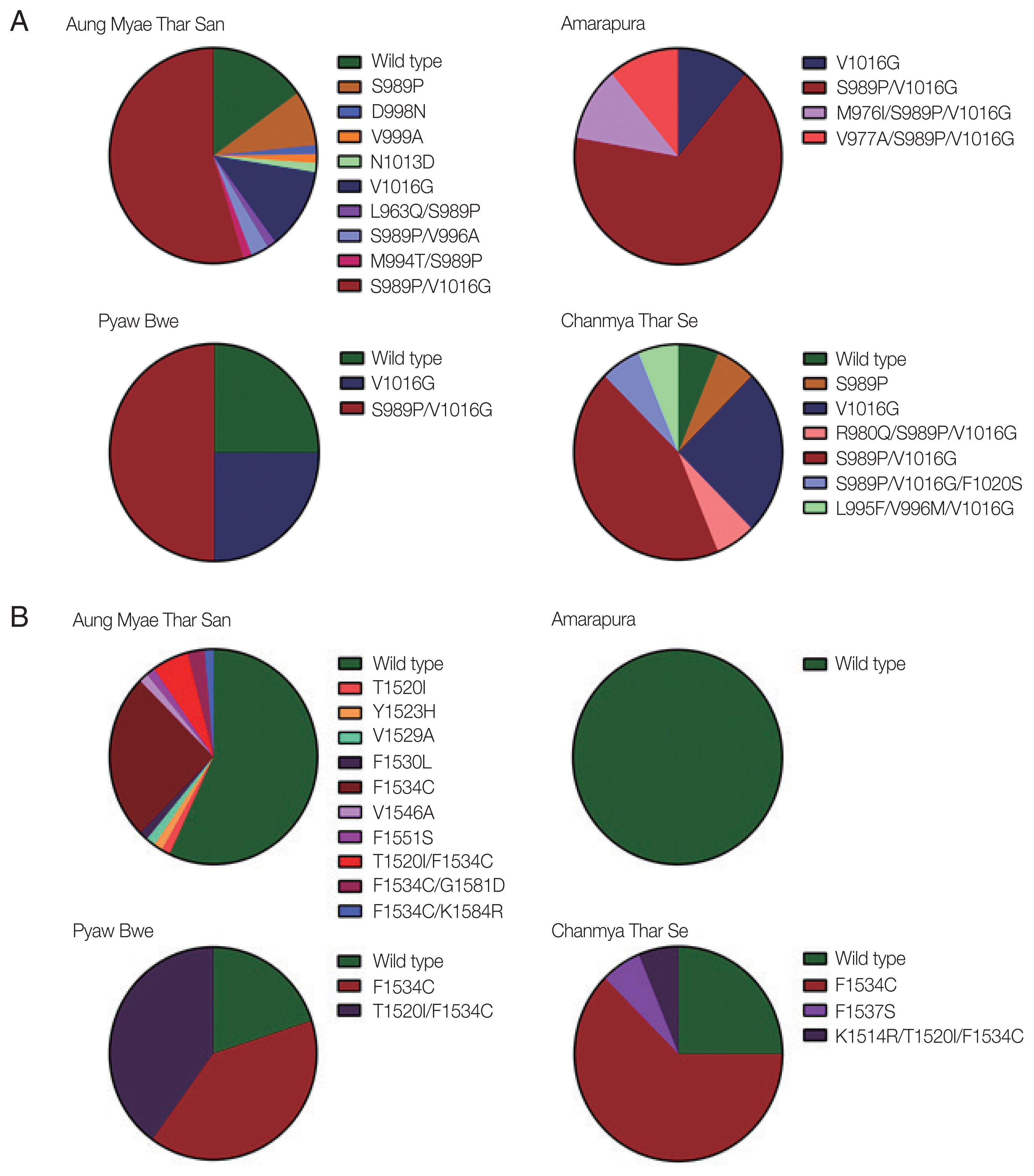

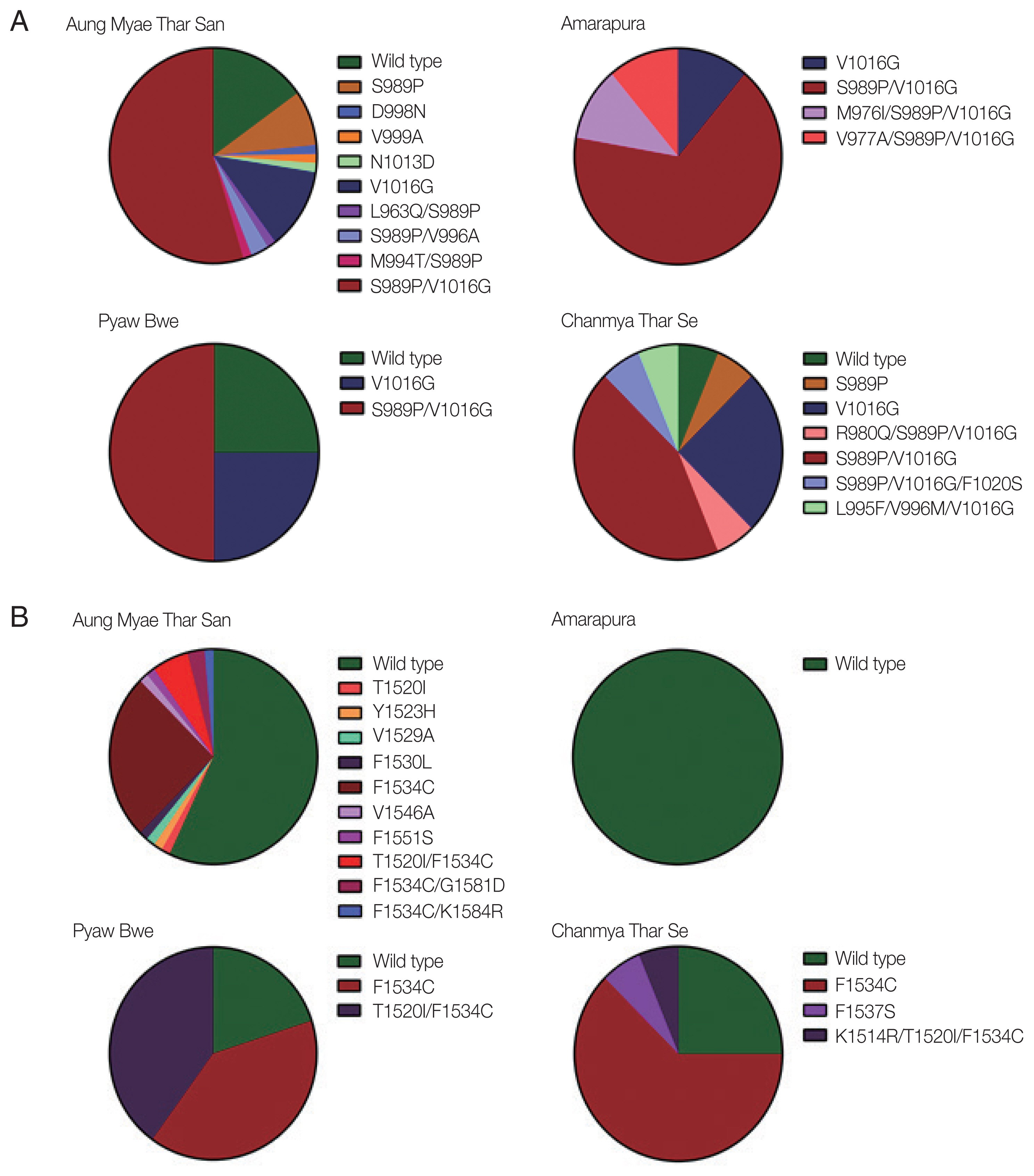

The mutations identified in domains II and III of the VSGC were distributed unevenly in Myanmar

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, and their frequencies varied with the geographical location. High frequencies of S989P/V1016G double mutation in domain II were detected in mosquitoes collected from all 4 collection sites ranging from 43.6% to 66.7% (

Fig. 3A). Frequencies of V1016G were also relatively high in mosquitoes collected from the 4 collection sites ranging from 11.1% to 25.0%. Meanwhile, S989P was detected in only mosquitoes collected in Aung Myae Thar San and Chanmya Thar Se. Other minor mutations found in domain II were mostly combined with either S989P or V1016G, except D998N, V999A, and N1013D. The overall frequencies of mutations found in domain III were lower than those in domain II in mosquitoes from all 4 collection sites (

Fig. 3B). F1534C was detected in mosquitoes collected from Aung Myae Thar San, Pyaw Bwe, and Chanmya Thar Se. However, this mutation was not detected in mosquitoes from Amarapura. T1520I was detected in mosquitoes collected only at Aung Myae Thar San. The T1520I/F1534C double mutation was observed in mosquitoes collected at Aung Myae Thar San and Pyaw Bwe with a frequency of 5.6% and 40.0%, respectively.

It has been reported that the 11 common

kdr mutations in the

VGSC are associated with insecticide resistance in

Ae. aegypti: V410L in domain I, G923V, L982W, S989P, I1011M/V, and V1016G/I in domain II, T1520I and F1534C in domain III, and D1763Y in domain IV [

13,

27]. High frequencies of S989P (68.6%), V1016G (73.5%), F1534C (40.1%), and T1520I (8.1%) were observed in

Ae. aegypti that indicate a relatively high level of insecticide resistance. Meanwhile, other mutations that are known to be associated with insecticide resistance were not detected in domains II and III of Myanmar

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. The S989P/V1016G double mutation, which confers higher pyrethroid resistance [

28], was detected in mosquitoes collected in all 4 collecting areas ranging from 43.6% to 66.7%. Similar or higher levels of S989P (78.8%), V1016G (84.4%), and S989P/V1016G (65.7%) were previously reported in

Ae. aegypti populations of Yangon, Myanmar [

29]. The values in Myanmar

Ae. aegypti were significantly higher than those of neighboring countries including India, Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia [

30–

33]. F1534C in domain III is also known to be closely associated with type I pyrethroid resistance [

34]. The frequency of this mutation in

Ae. aegypti analyzed in this study was also high (40.1%), which was higher than that observed in

Ae. aegypti (20.2%) from Yangon, Myanmar [

29]. Meanwhile, the rate of F1534C mutation differed from that of

Ae. aegypti populations in other neighboring countries, including Thailand (62.0%) [

31], India (79.0%) [

35], Vietnam (7.4%) [

32], and Malaysia (13.3%) [

34]. The frequencies of V1016G/F1534C and S989P/V1016G/F1534C were 30.1% and 23.5%, respectively, in

Ae. aegypti analyzed, while the frequency of T1520I was 8.1%. This mutation was previously identified in

Ae. aegypti from India and China [

35,

36], and now has been identified in the Myanmar

Ae. aegypti. It has been proposed that T1520I does not confer pyrethroid or DDT resistance by itself, nor does it increase F1534C-mediated resistance to DDT [

36]. However, considering that T1520I is usually tightly combined with F1534C, further studies are needed to determine the role of this mutation in insecticide resistance. Besides these well-known

kdr mutations in domains II and III, diverse mutations, alone or combined with other

kdr mutations, were identified in

Ae. aegypti from Mandalay region, Myanmar. Most of them were novel, even though their frequencies were generally low. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the role of these mutations in insecticide resistance.

In conclusion, high frequencies of kdr mutations were observed in the VGSC of Ae. aegypti in the Mandalay region, Myanmar, suggesting a high level of insecticide resistance. Therefore, the current insecticide application program in Mandalay region, Myanmar, should be carefully reconsidered to develop alternative methods for Ae. aegypti control. A limitation to this study was using pooled mosquito samples, rather than individual mosquitoes. A further study including larger sample sizes and individual Ae. aegypti mosquitoes is needed to determine the relative insecticide resistance of mosquitoes in the areas more clearly.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (NRF-2019K1A3A9A01000005).

Fig. 1Map of mosquito collection sites. Mosquito larvae and pupae were collected from 4 different areas of Mandalay region, Myanmar.

Fig. 2Distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations identified in the VGSC of Ae. aegypti from Myanmar. (A) Domain II region. A total of 13 mutations were identified. The frequencies of S989P and V1016G were 68.6% and 73.5%, respectively. The other mutations were detected with low frequencies ranging from 1.0% to 2.0%. (B) Domain III region. A total of 11 mutations were identified. The frequency of F1534C was 40.1%. T1520I was also found with a frequency of 8.1%. The other mutations were detected with low frequencies ranging from 1.0% to 2.0%.

Fig. 3Comparason on distribution and frequency of VGSC mutations in Myanmar Ae. aegypti collected from 4 study areas. (A) Domain II. The S989P, V1016G, and S989P/V1016G were identified with high frequencies in Ae. aegypti collected from all study areas. Minor mutations were identified as single or combined forms with S989P and/or V1016G. (B) Domain III. High frequency of F1534C was identified in Aung Myae Thar San, Pyaw Bwe and Chanmya Thar Se, but not in Amarapura. Minor mutations were identified as single or combined forms with F1543C.

References

- 1. Satoto TBT, Satrisno H, Lazuardi L, Diptyanusa A, Purwaningsih , Rumbiwati , Kuswati . Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti: an impact from human urbanization? PLoS One 2019;14:e0218079. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218079

- 2. Baruah S, Dutta P. Seasonal prevalence of Aedes aegypti in urban and industrial areas of Dibrugarh district, Assam. Trop Biomed 2013;30:434-443.

- 3. Shiff C. Vector control: methods for use by individuals and communities. Parasitol Today 1998;14:470. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-4758(98)01304-0

- 4. World Health Organization. Pesticides and their Application for the Control of Vectors and Pests of Public Health Importance. 6th ed. Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization; 2006, pp 9-20.

- 5. Dong K, Du Y, Rinkevich F, Nomura Y, Xu P, Wang L, Silver K, Zhorov BS. Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2014;50:1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.03.012

- 6. Hemingway J, Ranson H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol 2000;45:371-391. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371

- 7. Bingham G, Strode C, Tran L, Khoa PT, Jamet HP. Can piperonyl butoxide enhance the efficacy of pyrethroids against pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti? Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:492-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02717.x

- 8. Du Y, Nomura Y, Zhorov BS, Dong K. Sodium channel mutations and pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti. Insects 2016;7:60. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects7040060

- 9. Rinkevich FD, Du Y, Dong K. Diversity and convergence of sodium channel mutations involved in resistance to pyrethroids. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2013;106:93-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.02.007

- 10. World Heath Organization. Manual on Environmental Management for Mosquito Control with Special Emphasis on Malaria Vectors. Geneva, Switzerland. WHO Offset Publication; 1982, pp 4-283.

- 11. Narahashi T. Neuronal ion channels as the target sites of insecticides. Pharmacol Toxicol 1996;79:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0773.1996.tb00234.x

- 12. Narahashi T, Ginsburg KS, Nagata K, Song JH, Tatebayashi H. Ion channels as targets for insecticides. Neurotoxicology 1998;19:581-590.

- 13. Silver KS, Du Y, Nomura Y, Oliveira EE, Salgado VL, Zhorov BS, Dong K. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels as Insecticide Targets. Adv In Insect Phys 2014;46:389-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417010-0.00005-7

- 14. Sayono S, Hidayati AP, Fahri S, Sumanto D, Dharmana E, Hadisaputro S, Asih PB, Syafruddin D. Distribution of voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav) alleles among the Aedes aegypti populations in Central Java Province and its association with resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150577

- 15. Doherty RL, Westaway EG, Whitehead RH. Further studies of the aetiology of an epidemic of dengue in Queensland, 1954–1955. Med J Aust 1967;2:1078-1080.

- 16. Cleland JB, Bradley B, McDonald W. Dengue fever in Australia: its history and clinical course, its experimental transmission by Stegomyia fasciata, and the results of inoculation and other experiments. J Hyg (Lond) 1918;16:317-418. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022172400006690

- 17. Ross RW. The Newala epidemic III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic. J Hyg (Lond) 1956;54:177-191. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022172400044442

- 18. Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Moyes CL, Farlow AW, Scott TW, Hay SI. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760

- 19. Parham PE, Waldock J, Christophides GK, Hemming D, Agusto F, Evans KJ, Fefferman N, Gaff H, Gumel A, LaDeau S, Lenhart S, Mickens RE, Naumova EN, Ostfeld RS, Ready PD, Thomas MB, Velasco-Hernandez J, Michael E. Climate, environmental and socio-economic change: weighing up the balance in vector-borne disease transmission. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015;370:20130551. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0551

- 20. Servadio JL, Rosenthal SR, Carlson L, Bauer C. Climate patterns and mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in South and Southeast Asia. J Infect Public Health 2018;11:566-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.12.006

- 21. World Health Organization. Global strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control 2012–2020. Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization; 2012, pp 1-3.

- 22. Ngwe Tun MM, Kyaw AK, Makki N, Muthugala R, Nabeshima T, Inoue S, Hayasaka D, Moi ML, Buerano CC, Thwe SM, Thant KZ, Morita K. Characterization of the 2013 dengue epidemic in Myanmar with dengue virus 1 as the dominant serotype. Infect Genet Evol 2016;43:31-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2016.04.025

- 23. Kyaw AK, Ngwe Tun MM, Moi ML, Nabeshima T, Soe KT, Thwe SM, Myint AA, Maung KTT, Aung W, Hayasaka D, Buerano CC, Thant KZ, Morita K. Clinical, virological and epidemiological characterization of dengue outbreak in Myanmar, 2015. Epidemiol Infect 2017;145:1886-1897. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817000735

- 24. Department of Medical Researc, National Health Laboratories. Reports from Department of Medical Research (DMR) and National Health Laboratories (NHL). Ministry of Health in Myanmar; 2013.

- 25. Linn NN, Kyaw KWY, Shewade HD, Kyaw AMM, Tun MM, Khine SK, Linn NYY, Thi A, Lin Z. Notified dengue deaths in Myanmar (2017–18): profile and diagnosis delays. F1000Res 2020;9:579. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23699.1

- 26. Huang YM. The subgenus Stegomyia of Aedes in the Afrotropical region I. The Africanus group of species (Diptera: Culicidae). Gainesville, USA. American Entomological Institute; 1990, pp 10-42.

- 27. Hemingway J, Hawkes NJ, McCarroll L, Ranson H. The molecular basis of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2004;34:653-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.018

- 28. Son-Un P, Choovattanapakorn N, Saingamsook J, Yanola J, Lumjuan N, Walton C, Somboon P. Effect of relaxation of deltamethrin pressure on metabolic resistance in a pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) strain harboring fixed P989P and G1016G kdr alleles. J Med Entomol 2018;55:975-981. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjy037

- 29. Kawada H, Oo SZ, Thaung S, Kawashima E, Maung YN, Thu HM, Thant KZ, Minakawa N. Co-occurrence of point mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel of pyrethroid resistant Aedes aegypti populations in Myanmar. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e3032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003032

- 30. Saha P, Chatterjee M, Ballav S, Chowdhury A, Basu N, Maji AK. Prevalence of kdr mutations and insecticide susceptibility among natural population of Aedes aegypti in West Bengal. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215541

- 31. Plernsub S, Saingamsook J, Yanola J, Lumjuan N, Tippawangkosol P, Walton C, Somboon P. Temporal frequency of knockdown resistance mutations, F1534C and V1016G, in Aedes aegypti in Chiang Mai city, Thailand and the impact of the mutations on the efficiency of thermal fogging spray with pyrethroids. Acta Trop 2016;162:125-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.06.019

- 32. Kawada H, Higa Y, Komagata O, Kasai S, Tomita T, Thi Yen N, Loan LL, Sánchez RA, Takagi M. Widespread distribution of a newly found point mutation in voltage-gated sodium channel in pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti populations in Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009;3:e527. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000527

- 33. Ishak IH, Jaal Z, Ranson H, Wondji CS. Contrasting patterns of insecticide resistance and knockdown resistance (kdr) in the dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from Malaysia. Parasit Vectors 2015;8:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0797-2

- 34. Leong CS, Vythilingam I, Liew JW, Wong ML, Wan-Yusoff WS, Lau YL. Enzymatic and molecular characterization of insecticide resistance mechanisms in field populations of Aedes aegypti from Selangor, Malaysia. Parasit Vectors 2019;12:236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3472-1

- 35. Kushwah RB, Dykes CL, Kapoor N, Adak T, Singh OP. Pyrethroid-resistance and presence of two knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations, F1534C and a novel mutation T1520I, in Indian Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e3332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003332

- 36. Chen M, Du Y, Wu S, Nomura Y, Zhu G, Zhorov BS, Dong K. Molecular evidence of sequential evolution of DDT- and pyrethroid-resistant sodium channel in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019;13:e0007432. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007432

, Tong-Soo Kim4, Byoung-Kuk Na1,2,*

, Tong-Soo Kim4, Byoung-Kuk Na1,2,*