Functional characterization of glucose transporter 4 involved in glucose uptake in Clonorchis sinensis

Article information

Abstract

Clonorchis sinensis, which causes clonorchiasis, is prevalent in East Asian countries and poses notable health risks, including bile duct complications. Although praziquantel is the primary treatment for the disease, the emerging resistance among trematodes highlights the need for alternative strategies. Understanding the nutrient uptake mechanisms in trematodes, including C. sinensis, is crucial for developing future effective treatments. This study aimed to characterize the function of C. sinensis glucose transporter 4 (CsGTP4) and determine its role in nutrient uptake employing synthesized cDNA of adult C. sinensis worms. The functional characterization of CsGTP4 involved injecting its cRNA into Xenopus laevis oocytes and analyzing the deoxy-D-glucose uptake levels. The results demonstrated that deoxy-D-glucose uptake depended on the deoxy-D-glucose incubation and CsGTP4 expression time, but not sodium-dependent. The concentration-dependent uptake followed the Michaelis–Menten equation, with a Km value of 2.7 mM and a Vmax value of 476 pmol/oocyte/h based on the Lineweaver–Burk analysis. No uptake of radiolabeled α-ketoglutarate, p-aminohippurate, taurocholate, arginine, or carnitine was observed. The uptake of deoxy-D-glucose by CsGTP4 was significantly inhibited by unlabeled glucose and galactose in a concentration-dependent manner. It was significantly inhibited under strongly acidic and basic conditions. These insights into the glucose uptake kinetics and pH dependency of CsGTP4 provide a deeper understanding of nutrient acquisition in trematodes. This study contributes to the development of novel antiparasitic agents, addressing a considerable socioeconomic challenge in affected regions.

Introduction

Clonorchiasis is an overlooked parasitic illness acquired by ingesting uncooked freshwater fish infected with Clonorchis sinensis metacercaria(e). This infection is prevalent in East Asian countries, including Korea [1], China [2], Vietnam [3], and Russia [4], with over 15 million cases. More than 200 million people are at risk of infection globally [4]. Clonorchiasis is frequently missed because of the absence of subjective symptoms or specific indicators in the early stages of infection [5]. The disease mainly affects the bile ducts, leading to various clinical symptoms, such as bile duct enlargement, obstructive jaundice, and the formation of calculi. Severe chronic infections can result in cholecystitis, cholangitis, and cholangiocarcinoma [6].

Praziquantel (PZQ) is the first-line chemotherapeutics combating clonorchiasis. The mode of action of PZQ has been studied in schistosomes, where it targeted the melastatin ion channels localized on the tegument [7], resulting in an increase in the calcium influx within a short period in the parasite and leading to paralysis [7]. The external surface of trematodes fulfills essential biological roles, including nutrient absorption, protection, and sensory perception, all of which are necessary for their survival. It is important to understand the biological attributes of the external surface and the material transport system of the trematode to efficiently prevent and treat the illnesses. However, the process through which trematodes acquire nutrients via their transporter system remains largely unknown.

Cells need to exchange chemicals with their surrounding micro environment and transport hydrophilic molecules across the plasma membrane to survive. They must uptake nutrients, carbohydrates, and amino acids, excrete waste products such as carbon dioxide and metabolites, and regulate inorganic ion concentrations. Six-carbon glucose is essential for protein and lipid synthesis, energy production, and homeostasis in eukaryotic cells, and most mammalian cells require ATP, which is produced from glucose [8]. Glucose is also used in glycerol biosynthesis for neutral lipids and as a precursor for nonessential amino acids. Moreover, it is involved in lactose and carbohydrate synthesis in lactating animals [9].

Hydrophilic molecules cannot pass through the phospholipid bilayer of eukaryotic cell membranes. Initially, glucose was thought to enter cells directly via diffusion because of its modest molecular weight; however, it was later discovered to use specific cell membrane transport proteins [10,11]. Two types of carrier proteins, sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLTs) and glucose transporters (GLUTs) were identified to facilitate glucose entry into the cell [8]. SGLT and GLUT are membrane proteins with 14 and fewer than 12 transmembrane domains, respectively [12]. GLUTs are categorized into 3 primary classes (I, II, and III) and comprise 14 subtypes (GLUT 1–14) [13]. Some parasites, such as Trypanosoma brucei, Leishmania mexicana, Plasmodium vivax, and P. falciparum, have been identified to absorb glucose via GLUTs [14–16]. The GLUTs in trematodes have mainly been studied in the Schistosoma species and are named Schistosome GLUTs (SGTP) 1, 2, and 4 [17]. The Schistosoma species absorb nutrients through the external surface of the parasite via SGTP1 in the basal membrane and SGTP4 in the tegument, facilitating interactions with the host [18,19].

Our previous research confirmed the functional activity of the first GLUT in C. sinensis (CsGLUT) named CsGTP1 (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] accession number: GAA56139.1), which exhibited strong D-glucose selectivity and transport activity [20]. However, information about the functional activity of other GLUTs involved in glucose uptake in C. sinensis is lacking. Therefore, this study focused on investigating the functional activity of the second CsGLUT, C. sinensis glucose transporter 4 (CsGTP4). This research aimed to enhance our understanding of monosaccharide absorption in C. sinensis and contribute to the development of novel therapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The animal experiment protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no. INHA161208-460) at Inha University, accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALC).

Chemicals

Radiolabeled compounds, including [3H] deoxy-D-glucose (32.5 Ci/mmol), [3H] arginine (50.5 Ci/mmol), [14C] α-ketoglutaric acid (54.8 mCi/mmol), [14C] p-aminohippurate (52.7 mCi/mmol), [3H] taurocholate (15.5 Ci/mmol), and [14C] carnitine (50.3 mCi/mmol), were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Science Products (Boston, MA, USA). All other chemicals and reagents were sourced commercially and were of analytical grade.

Computational in silico analysis

The putative CsGTP4 nucleotide sequence was obtained from the NCBI (accession number: DF144168.1). The corresponding amino acid sequence encodes the solute carrier family 2 facilitated GLUT member 3 (accession number: GAA56140.1). Other GLUT homolog genes from the flukes were obtained from the NCBI database by BlastP, and the sequences were aligned using the Clustal W program (http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp). The evolutionary history of the GLUTs in the flukes was inferred using the MEGA11 software (http://www.megasoftware.net) by implementing maximum-likelihood analysis with a bootstrap test of 1,000 pseudo-replications to enhance the robustness.

The membrane-spanning topology was determined using the TMpred server (https://ftp.vital-it.ch/pub/software/unix/tmpred/www/TMPRED_form.html), which predicted the presence of 12 potential transmembrane domains. The tertiary structure of CsGTP4 was further analyzed by submitting the putative CsGTP4 sequences to the SWISS-MODEL server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org), a homology-based modeling tool that identified suitable structure templates, as described elsewhere [21]. The final tertiary structure model was selected and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphic system, version 3.0. The AutoDock Vina software was used to generate the D-glucose-binding mode of CsGTP4 [22].

Collection of C. sinensis adult worms

Experimental C. sinensis metacercariae were obtained by collecting Pseudorasbora parva and Gnathopogon coreanus from the Nam River in Jinju, Korea, an area known for high infection rates. The fish were enzymatically digested, after which the metacercariae were isolated. A 6-week-old female New Zealand white rabbit (Samtako Bio, Osan, Korea) was raised in a controlled environment for 8 weeks with access to water and grain food. Four weeks after infection, eggs were detected in the rabbit’s stool using formalin-ether techniques. Adult C. sinensis was collected from the bile ducts of the animal 8 weeks post-infection.

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Adult C. sinensis worms (100 mg) were lysed with 1 ml of Tri Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and homogenized at 10,000 rpm for 20 sec using a tissue homogenizer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The solution was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and total RNA isolation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The collected RNA was measured and preserved at −70°C.

For the reverse transcription of CsGTP4, 500 ng of total RNA was mixed with 5 units of Avian Myeloblastosis Virus reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mM dNTP (ELPIS-Biotech, Daejeon, Korea), and 2.5 μM oligo dT-adapter primer (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) in 30 μl final volume. The mixture was incubated at 42°C for 30 min, heated to 99°C for 5 min, and finally stored at 4°C.

Cloning of CsGTP4

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted with 3 μl C. sinensis cDNA, 3 μl dNTP (2.5 mM each), 1 unit Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), 3 μl 10×PCR reaction buffer, 1 μl forward and reverse primer (10 μM) each (Supplementary Table S1), and adjusted to 30 μl with DNase- and RNase-free distilled water. The thermocycler conditions for the CsGTP4 included pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 45 sec, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The amplicon was electrophoresed at 100 V for 30 min onto a 1.5% agarose gel. The amplicon was eluted using a gel extraction kit (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Subcloning was performed on the pGEM-T Easy TA cloning vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). After verifying the correct nucleotide sequence, the plasmids were digested with EcoR I and the DNA segments were eluted for the overlap extension PCR.

The overlap extension PCR was performed using a reaction mixture consisting of 2 μl each amplicon, 3 μl dNTPs (2.5 mM each), 2 units LA Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), 3 μl 10×PCR reaction buffer, 4 μl 25 mM MgCl2, the first forward primer, and the third reverse primer. Conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product was subcloned into the TA cloning vector (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The nucleotide sequence was confirmed via the dye-termination method using ABI Prism 3730 sequencer (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea).

Preparation of cRNA and substrate uptake in Xenopus laevis oocytes

The Xenopus laevis oocyte expression system, a widely used method for characterizing transporters, was utilized to assess the glucose uptake properties [23]. The plasmid DNA containing CsGTP4 cDNA was completely digested using the Xho I (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) to synthesize the complementary RNA (cRNA) using the mMESSAGE mMACHINETM T7 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The synthetic cRNA was concentrated and purified. The cRNA was preserved at −70°C until oocyte injection.

Xenopus laevis adult females were raised at the Xenopus Resource Center (Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea). The oocytes were prepared by freezing them in ice for 1 h, dissecting the abdomen, and turning the ovarian lobe. Yellow and brown eggs at stages V–VI were collected and transferred to Barth’s solution. The yolk skin was vigorously agitated at room temperature for 1 h and the defolliculated follicular cells were washed 3 to 5 times.

For CsGTP4 cRNA microinjection, 50 ng per oocyte was introduced into the follicular cells. An equivalent volume of distilled water was administered to the control group. The injected follicular cells were cultured at 18°C in Barth’s solution supplemented with 50 μg/ml gentamicin and 2 mM sodium pyruvate as a nutrient. Glucose uptake was assessed 2–3 days after culture to evaluate the CsGTP4 expression. Substrate uptake were conducted at room temperature in ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) using an isotope-labeled substrate for over 1 h. The reaction was stopped by adding ice-cold ND96 solution, followed by 3 to 4 washes with the same solution. Follicular cells were lysed in 10% SDS for 1 h, and 2 ml of the scintillation cocktail ULTIMA GOLD AB (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was added. The radioactivity was measured using a MicroBeta2 β-counter (PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland).

Kinetics of the glucose uptake via CsGTP4

The kinetic parameters for CsGTP4-mediated glucose uptake were estimated using the following equation:

where v is the substrate uptake rate (pmol/oocyte/h), S is the substrate concentration in the medium (mM), Km is the Michaelis–Menten constant (mM), and Vmax is the maximum uptake rate (pmol/oocyte/h). The parameters were determined by fitting the equation to the CsGTP4 velocity, which was calculated by subtracting the glucose transport velocity in noninjected oocytes from that in CsGTP4-expressing oocytes. The fitting graph was created using an iterative nonlinear least squares method with the multiple. The input data, weighted by the reciprocal of the observed values, were fitted using the Damping Gauss-Newton method. The resulting fitted line was then transformed into the 1/S versus 1/V format for the Lineweaver–Burk analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for each group in all experiments was performed using the student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism v8, with significance levels considered as *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

Results

Schematic characteristics of CsGTP4

The open reading frame of the nucleotide sequence that encoded CsGTP4 was composed of 1,488 base pairs that encoded a 496 amino acid with a calculated molecular mass of 54.0 kDa. The putative topological model of CsGTP4 shared characteristic features and similarities with class I and II human GLUT, including 12 transmembrane domains (TMs; Supplementary Fig. S2A). This class typically comprises type III multipass transmembrane proteins with intracellular N- (NTD) and C-terminal domains (CTD) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Additionally, TM6 and TM7 are connected by a long intracellular region containing 6 TMs in both NTD and CTD regions (Supplementary Figs. S2A, S3). Using the SWISS-MODEL server, the tertiary structure of CsGTP4 was determined. The solute carrier family 2 facilitated GLUT member 3 (PDB ID: 7spt.1) identified as the superior template, showing the best-fitting structure (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The tertiary structure revealed the presence of 12 major alpha-helices within the lipid bilayer region of CsGTP4. The long loop in the intracellular region, consisting of 4 alpha-helices (ICH), acted as a bridge connecting TMs 6 and 7 (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B). Overall structure of CsGTP4 displayed a conserved core structure shared with the GLUTs found in other organisms.

The relationships between putative GLUT-related genes were determined by comparing the CsGTP4 sequence from other flukes obtained from the NCBI database. Sequence analysis of homology among GLUT-related proteins of other flukes to CsGTP4 indicated the following levels: Fasciola gigantica (TPP66153.1), 65.1%; F. hepatica (THD25344.1), 65.1%; F. buski (KAA0198350.1), 65.5%; Echinostoma caproni (VDP65315.1), 65.1%; Opisthorchis felineus (TGZ55240.1), 94.4%; O. viverrini (XP_009162471.1), 95.0%; Paragonimus westermani (KAF8566867.1), 64.0%; Schistosoma bovis (CAH8515673.1), 60.4%; S. haematobium (XP_051068143.1), 60.4%; S. mekongi (KAK4469537.1), 60.2%; S. japonicum (TNN18001.1), 57.4%; and Clonorchis sinensis (CsGLUT, GAA56139.1), 60.3% (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

Uptake properties of CsGTP4

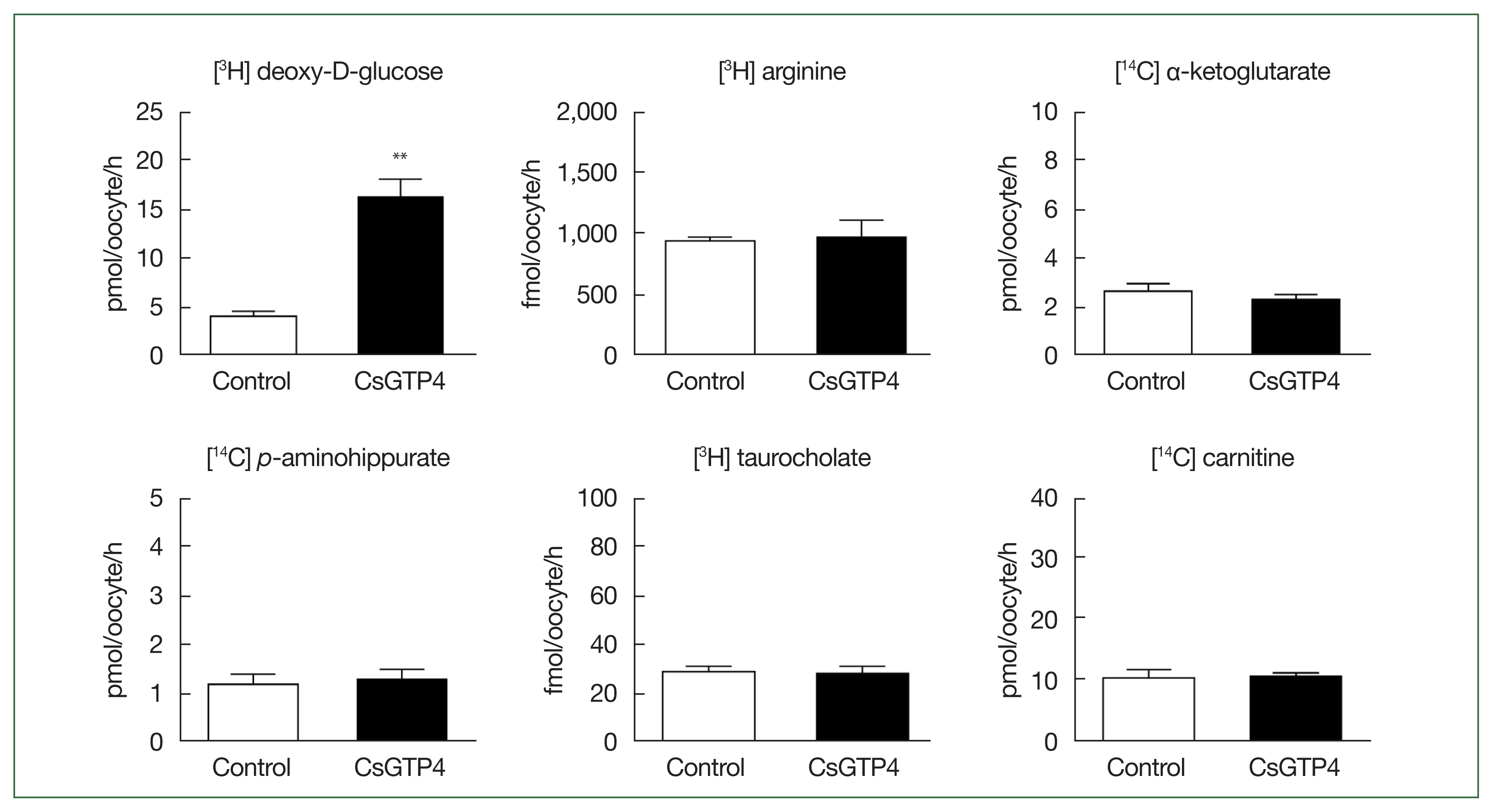

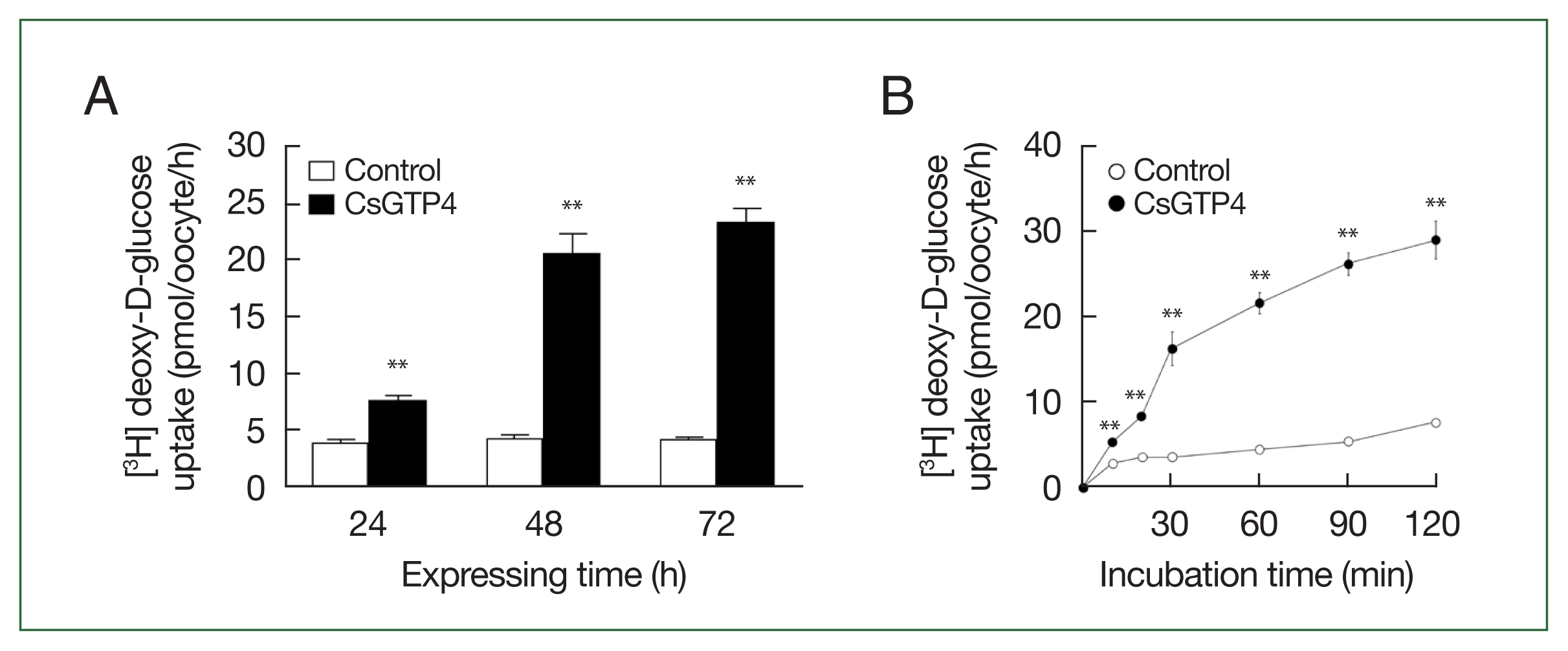

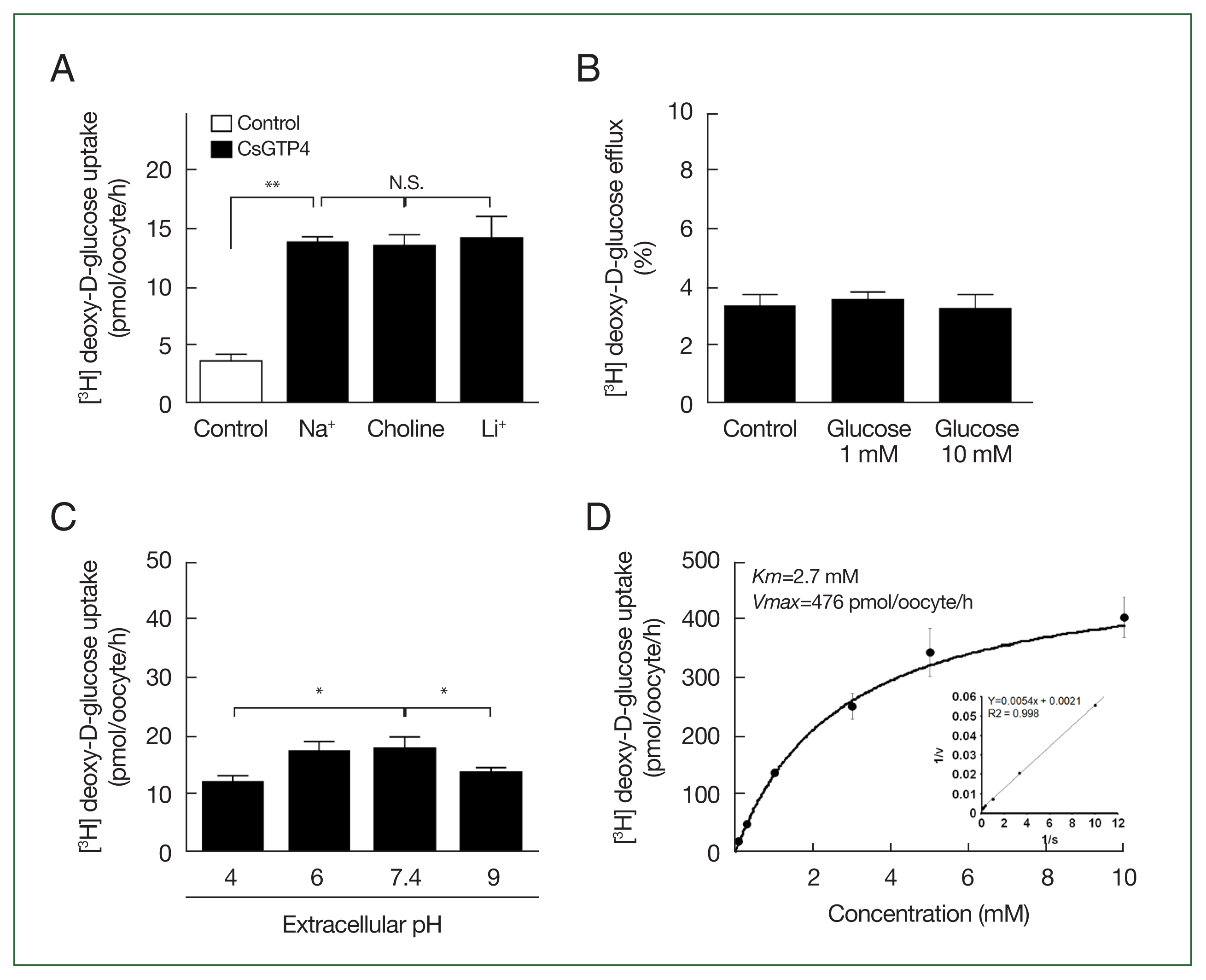

The X. laevis oocyte expression system was used to investigate the transport characteristics of CsGTP4 with various substrates. The uptake rate of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose in oocytes expressing CsGTP4 was significantly higher than that in the control oocytes (Fig. 1). However, other substrates, including [3H] arginine, [14C] α-ketoglutaric acid, [14C] p-aminohippurate, [3H] taurocholate, and [14C] carnitine, showed no significant uptake activity (Fig. 1). The increase in the trans-uptake activity of CsGTP4 was dependent of the expression (24–72 h post-cRNA injection) and incubation (15–120 min) times (Fig. 2A, B), which indicate that CsGTP4 binds and translocates [3H] deoxy-D-glucose into the oocyte. The uptake solution (ND96 containing 96 mM Na+ ions) was replaced with equimolar concentrations of choline and lithium ions to confirm its sodium dependency. The uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose by CsGTP4 did not change after 1 h (Fig. 3A). Investigations of the trans-stimulatory effect of CsGTP4 revealed that the efflux of the preloaded [3H] deoxy-D-glucose was not stimulated by the excess amount of nonradioactive glucose (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that CsGTP4 functions as a uniporter with high glucose selectivity. The optimal pH condition was determined by testing the pH levels at 4, 6, 7.4, and 9. Significantly reduced uptake at pH 4 and 9 was observed (Fig. 3C). The concentration-dependent uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose mediated by CsGTP4 showed saturable kinetics and followed the Michaelis–Menten equation. Nonlinear regression analysis yielded a Km value of 2.7 mM with a Vmax value of 476 pmol/oocyte/h (Fig. 3D).

CsGTP4-mediated uptake of deoxy-D-glucose. The uptake rates of the radiolabeled compounds were measured in water-injected (Control, white bar) and CsGTP4-expressing (black bar) oocytes for 1 h (mean±SE, n=8–10). The concentration of the injected substrate was as follows: [3H] deoxy-D-glucose, 100 μM; [3H] arginine, 100 nM; [14C] α-ketoglutarate, 5 μM; [14C] p-aminohippurate, 10 μM; [3H] taurocholate, 200 nM; and [14C] carnitine, 40 nM. Significant differences were calculated using the student’s t-test. **P<0.01.

Time dependency of deoxy-D-glucose transport via CsGTP4. (A) The uptake of 100 μM [3H] deoxy-D-glucose in the CsGTP4-expressing or water-injected (control) oocytes was measured at the indicated CsGTP4 expression times. (B) The uptake of 100 μM [3H] deoxy-D-glucose in control (open circle) and CsGTP4-expressing (closed circle) oocytes was measured for an incubation period of 120 min at 10–30 min intervals. All results are represented as mean±SE (n=6–8). Significant differences in D-glucose uptake levels between the control and CsGTP4-expressing oocytes were calculated using the student’s t-test. **P<0.01.

Glucose transport properties of CsGTP4. (A) Effect of extracellular cation on [3H] deoxy-D-glucose uptake in oocytes expressing CsGTP4. The uptake rate of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose (100 μM) was measured in the presence or absence of extracellular Na+. Extracellular Na+ was replaced with equimolar concentrations of choline and lithium-ion. The results are represented as the mean±SE (n=6–8). N.S.,not significant. **P<0.01. (B) The trans-stimulatory effect and concentration dependence of the CsGTP4-mediated uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose. A lack of a trans-stimulatory effect of glucose on the CsGTP4-mediated glucose efflux was observed. Oocytes expressing CsGTP4 were incubated with 100 μM [3H] deoxy-D-glucose for 1 h and transferred to ND96 solution with or without (control) 1 mM or 10 mM unlabeled glucose. The efflux amount of glucose within 1 h was shown as the percentage of the preloaded amount. (C) Various extracellular pH conditions affected the [3H] deoxy-D-glucose (100 μM) uptake level. Specifically, low and high pH significantly reduced [3H] deoxy-D-glucose (100 μM) uptake via CsGTP4. Statistical analysis was performed using the student’s t-test to compare the results with the pH 7.4 group, representing neutral conditions *P<0.05. (D) The saturation of CsGTP4-mediated uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose. The uptake rates of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose by the control (water-injected) or CsGTP4-expressing oocytes for 1 h were measured at variable concentrations (mean±S.E.; n=6–8). Inset, Lineweaver–Burk analysis of the concentration-dependent uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose. V, velocity; S, concentration of D-glucose.

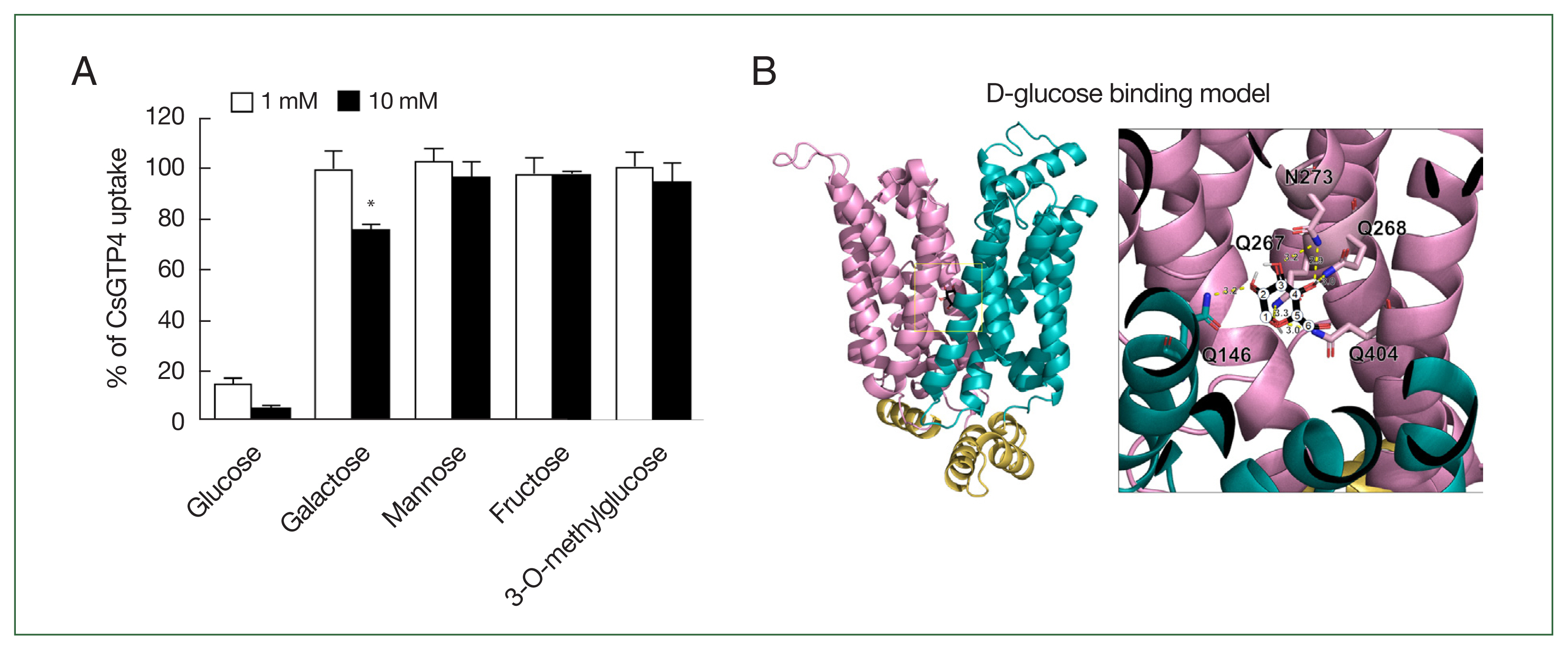

Substrate selectivity and the substrate binding model of CsGTP4

An inhibition study was conducted to investigate the selectivity of monosaccharides for CsGTP4. Strong inhibition was observed with glucose at concentrations of 1 and 10 mM. Additionally, galactose exhibited mild inhibition, reducing [3H] deoxy-D-glucose uptake by 24.0±1.9% at a concentration of 10 mM (Fig. 4A). In contrast, other monosaccharides, including mannose, fructose, and nonmetabolizable glucose analog 3-O-methylglucose, were not transported by CsGTP4.

Active analogue and substrate binding model on CsGTP4. (A) Uptake assays were carried out with [3H] deoxy-D-glucose using various concentrations of sugar derivates, including glucose (control), galactose, mannose, fructose, and 3-O-methylglucose. Significant differences were calculated using the student’s t-test. *P<0.05. (B) The coordination of D-glucose in CsGTP4 is depicted in the structure, with core residues for glucose binding. The number of carbons is represented as numeric circles, and the interactions between the 2 molecules are illustrated as yellow dotted lines with predicted distances (Å). The tertiary structure of CsGTP4 shows putative D-glucose-binding residues, including Gln 146, Gln 267, Gln 268, Asn 273, and Gln 404, depicted with their side chains.

The putative glucose-binding pocket was predicted through amino acid sequence alignment and tertiary structure modeling based on solute carrier family 2 and facilitated GLUT member 3 (PDB ID: 7spt.1). The tertiary structure of CsGTP4 revealed conserved amino acid residues spanning multiple TMs, in which core residues involved in glucose binding were positioned at Q146, Q267, Q268, N273, and Q404, with each residue within less than 3.3 Å to glucose (Fig. 4B). The molecular docking simulations indicated a perfect fit with zero root mean square deviation lower and upper bound matches (Fig. 4B). The calculated binding affinities were −5.6 kcal/mol for glucose.

Discussion

Praziquantel has long served as the primary anthelmintic drug for treating flukes, such as C. sinensis, for over 4 decades. PZQ works by enhancing the permeability of calcium ions through the calcium channel, leading to parasite contraction and expulsion from the host [24–26]. However, resistance to PZQ has been reported in schistosomes from Senegal and Egypt; thus, there is an urgent demand for the development of alternative anthelmintic drugs [27].

One promising approach for treating parasites involves selectively starving them by blocking their nutrient uptake, a method known as “selective starvation” [28]. Glucose is an energy source and a structural building block for all living cells. Glucose and other sugars are hydrophilic molecules that must be transported across the biological lipid bilayer membrane through a carrier-mediated transport process [29]. The transport of glucose across the cell membrane is facilitated by GLUT and SGLT proteins. GLUT is ubiquitously expressed across all cell types and plays a crucial role in the biosynthesis of biomolecules, as well as in generating and using glucose as an energy source for cellular metabolism. Recent data indicate that glucose uptake and metabolism are vital for parasite survival. For instance, compound 3,361, also known as the O-3 derivative, was specifically designed to block Plasmodium falciparum hexose transporters, which are GLUTs present throughout the intraerythrocytic stage in protozoan parasites. This compound has shown efficacy in treating infections caused by the Plasmodium species [16,28]. Anaerobic trematodes, such as schistosomes, metabolize glucose at a rate of 5 h per unit of dry weight [30]. Conversely, adult C. sinensis, also an anaerobic trematode, consumes 1.13 mg of glucose per hour per unit of wet weight [31–33]. These findings suggest that GLUT is crucial for the parasite's survival during the infection stage and highlight its potential as a significant target for treating parasitic diseases [34].

The glucose uptake in C. sinensis is facilitated by GLUT (also known as GTP) and SGLT transporters in the tegument. These transporters were confirmed to have higher transcription levels in adult worms than in metacercariae [35]. The results on glucose uptake properties via CsGTP4 allowed for a direct comparison with previous study on CsGLUT (CsGTP1, NCBI accession number. GAA56139.1), which was the first to describe the function of the GLUT in C. sinensis [20]. The localization of CsGTP1 was confirmed in the sperm and testis, whereas CsGTP4 was localized in the suckers, mesenchymal tissues, and tegument of the adult worm [35]. Despite the different localization patterns, both transporters showed similar glucose uptake properties. They mediate the transport of D-glucose in a time-dependent but sodium-independent manner and have been identified as uniporters [20]. The CsGTP1 showed a Km value of 588.5±53.0 μM [20], while that of CsGTP4 was 2.7 mM in the current study. This direct comparison indicated that CsGTP1 has a 4.6-fold higher D-glucose affinity and transport activity in C. sinensis. The substrate selectivity of CsGTP1 was not significant for the other monosaccharides; however, CsGTP4 possibly uptakes galactose with limited selectivity. The impact of extracellular pH on the uptake of [3H] deoxy-D-glucose via CsGTP4 appeared to diminish under strong acidic or basic conditions, indicating that CsGTP4 might be influenced by pH. The study provides valuable insights into the glucose uptake properties of CsGTP4 and its functional role in C. sinensis. The investigation into pH sensitivity and potential galactose uptake enhances our understanding of the transport characteristics of CsGTP4.

Using GLUTs in C. sinensis is crucial for understanding the nutrient uptake in all trematode species, including C. sinensis. Recent functional investigations of parasite transporters have revitalized efforts in developing antiparasitic medications [23,36,37]. Therefore, further in-depth studies are required to significantly influence the development of parasite treatments.

Supplementary Information

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Han JH, Cha SH

Data curation: Jun H, Lee WJ, Park YK, Han JH, Cha SH

Formal analysis: Jun H, Mazigo E, Lee WJ, Cha SH

Funding acquisition: Han JH, Cha SH

Investigation: Jun H

Methodology: Park YK, Han JH, Cha SH

Project administration: Han JH, Cha SH

Resources: Park YK, Cha SH

Software: Han JH, Cha SH

Supervision: Park YK, Han JH, Cha SH

Validation: Mazigo E, Han JH, Cha SH

Visualization: Mazigo E, Park YK, Han JH

Writing – original draft: Jun H

Writing – review & editing: Mazigo E, Han JH, Cha SH

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgments

This project was partially supported by funding provided by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00240627) (J. H. H.) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017R1D1A1B03034588) (S. H. C.). Adult Xenopus laevis was obtained from the Korean Xenopus Resource Center for Research.