Abstract

Opisthorchis viverrini (OV) infection, which can progress to cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), poses a critical public health challenge. While numerous studies have investigated behavior modification programs aimed at preventing OV and CCA, the effectiveness of these interventions remains inconclusive. This systematic review and meta-analysis sought to synthesize evidence on the efficacy of behavior modification programs, particularly those based on self-efficacy, in preventing OV and CCA. We reviewed experimental and quasi-experimental studies, comprising 2-group comparisons or 1-group pretest-posttest designs, that evaluated health education interventions focused on behavior modification for OV and CCA prevention. Relevant literatures was systematically retrieved from the PubMed, Google Scholar, ThaiJo, and ThaiLis databases. Of 702 identified studies, 13 met the systematic review and meta-analysis inclusion criteria. The analysis assessed the quality of the studies, extracted data, and evaluated the risk of bias. Standardized mean differences were calculated to determine the impact of self-efficacy–based programs on knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior modification. The results indicated significant post-intervention improvements in all outcomes (P<0.001) despite high heterogeneity in knowledge (I2=76%), self-efficacy (I2=77%), and behavior modification (I2=93%). The experimental group demonstrated significantly more significant improvements in knowledge (mean difference=1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.36–1.68), self-efficacy (mean difference=1.08, 95% CI=0.90–1.26), and behavior modification (mean difference=1.78, 95% CI=1.63–1.92) compared to the comparison group, with I2 values of 74%, 84%, and 92%, respectively. In conclusion, health education programs grounded in self-efficacy principles effectively enhance knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior modification to prevent OV and CCA. These findings suggest that self-efficacy–based behavior modification programs may also apply to the prevention of other diseases.

-

Key words: Health education, self-efficacy, Opisthorchis viverrini, cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

Opisthorchis viverrini (OV) infection and its associated cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) are critical public health concerns, especially in Southeast Asia, where the disease burden is highest. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified OV as a Group 1 biological carcinogen due to its well-established role in the etiology of CCA [

1]. OV transmission occurs primarily through consuming raw or undercooked freshwater fish, particularly cyprinid species, commonly prepared in traditional dishes such as raw fish salad and fermented fish. Humans and domestic animals, including cats and dogs, act as definitive hosts, contributing to the contamination of water sources and sustaining the OV transmission cycle [

2]. This ongoing transmission underscores the need for effective public health interventions to break the cycle and reduce the associated risks of CCA in endemic regions.

Although public health interventions have successfully reduced the prevalence of OV in Thailand—from 16.3% in 2016 to 4.3% in 2020—certain regions, especially in the northeast, continue to report high infection rates, with 4.97% still affected [

3]. Despite this reduction, OV infection and CCA disproportionately affect individuals in their working years (40–60 years), creating significant economic and social burdens. The annual cost of treating CCA in Thailand is estimated at 1.96 billion Baht (approximately 56 million US dollars), exerting a substantial strain on the healthcare system and reducing the quality of life for affected individuals and their families [

2–

4]. These challenges emphasize the critical need for effective preventive measures that target OV infection at its source, with the potential to alleviate the long-term healthcare burden associated with CCA.

Behavior modification strategies have been at the forefront of efforts to prevent OV and CCA, with many interventions based on Albert Bandura’s self-efficacy theory [

5]. According to Bandura [

5], self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s ability to influence outcomes through personal actions, is a crucial determinant of motivation and persistence in health behavior change. Health education programs that enhance self-efficacy are thought to increase individuals’ likelihood of adopting behaviors that reduce the risk of OV infection, such as avoiding high-risk foods like raw or undercooked fish.

However, despite the theoretical promise of self-efficacy–based interventions, evidence regarding their effectiveness in preventing OV and CCA remains inconsistent. Some studies have reported positive behavior change following self-efficacy interventions, while others have found limited or no impact [

6,

7]. These variations may stem from differences in study design, target populations, and intervention delivery, making it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the general effectiveness of self-efficacy approaches for OV and CCA prevention.

This gap in the literature underscores the need for a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the available evidence on the impact of self-efficacy–based health education programs for OV and CCA prevention. A comprehensive analysis of these interventions could provide more precise guidance for public health authorities and policymakers on designing and implementing more effective behavior modification programs. Additionally, this study explores whether the principles of self-efficacy can be applied to other areas of infectious disease prevention, potentially broadening the impact of these findings across multiple public health domains. Consequently, this study aimed to review the literature on the effectiveness of self-efficacy–based health education programs in preventing OV and CCA.

Methods

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Search method

A comprehensive search for relevant studies was conducted between February and May 2022. Studies published in English up to May 31, 2022, were considered for inclusion. The databases utilized for the search included PubMed, Google Scholar, ThaiJo, and ThaiLis. The PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) framework was applied to define search terms. The population was defined as the general public; the intervention focused on health education or self-efficacy programs; the comparison involved a comparison group; and the outcome focused on preventive behaviors, liver fluke infection, OV, and CCA. The search terms used were: “health education program” OR “self-efficacy program” AND “liver fluke” OR “Opisthorchis viverrini” AND “cholangiocarcinoma” OR “bile duct cancer.”

Inclusion criteria

(1) Quantitative research studies, including experimental or quasi-experimental designs comparing 2 groups and/or one-group pretest-posttest designs, evaluate health education programs’ effects on behavior modification for preventing OV and CCA; (2) published up to May 31, 2022, focusing on health education programs based on knowledge application and self-efficacy; and (3) studies containing sufficient data for meta-analysis, including mean, standard deviation, and sample sizes for experimental and comparison groups.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Qualitative research, (2) review articles or editorial articles, (3) conference proceedings, (4) studies where the full text could not be obtained, and (5) articles that were meta-analyses.

Search outcomes

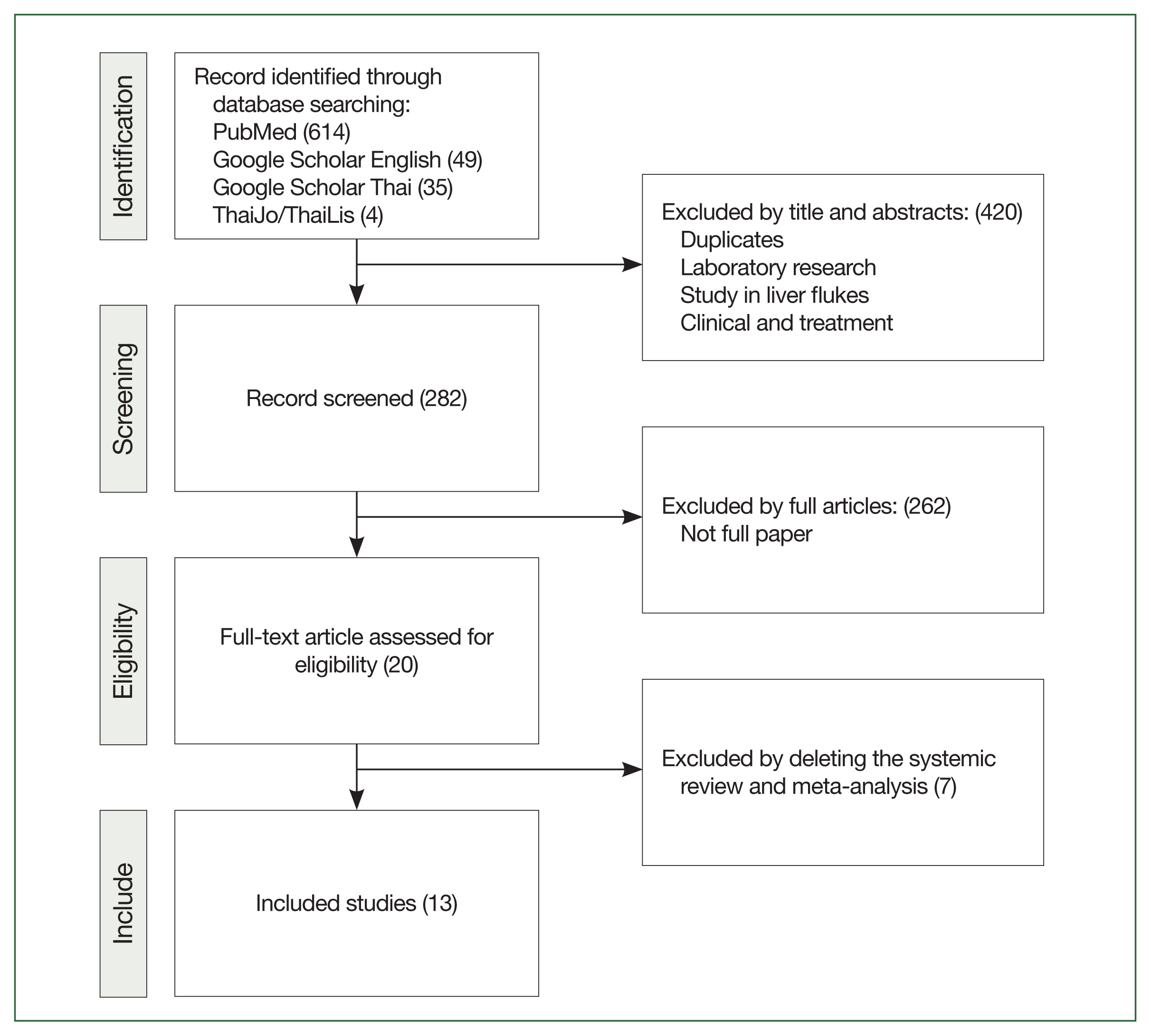

The initial search was performed independently by 2 researchers, followed by a third researcher who resolved any disagreements regarding study inclusion. A total of 702 studies were identified: 614 from PubMed, 49 from Google Scholar (English), 35 from Google Scholar (Thai), and 4 from ThaiLis and ThaiJo. In the first screening phase, titles and abstracts were reviewed, excluding 420 irrelevant studies, reviews, or articles without full text. This left 282 studies for further review. In the second round, abstracts and full texts were carefully analyzed, excluding 262 studies due to insufficient data. In the third round, the remaining studies were assessed for research design suitability for systematic review and meta-analysis. An additional 20 studies were excluded due to inadequate data for meta-analysis, leaving 13 studies for the final analysis (

Fig. 1).

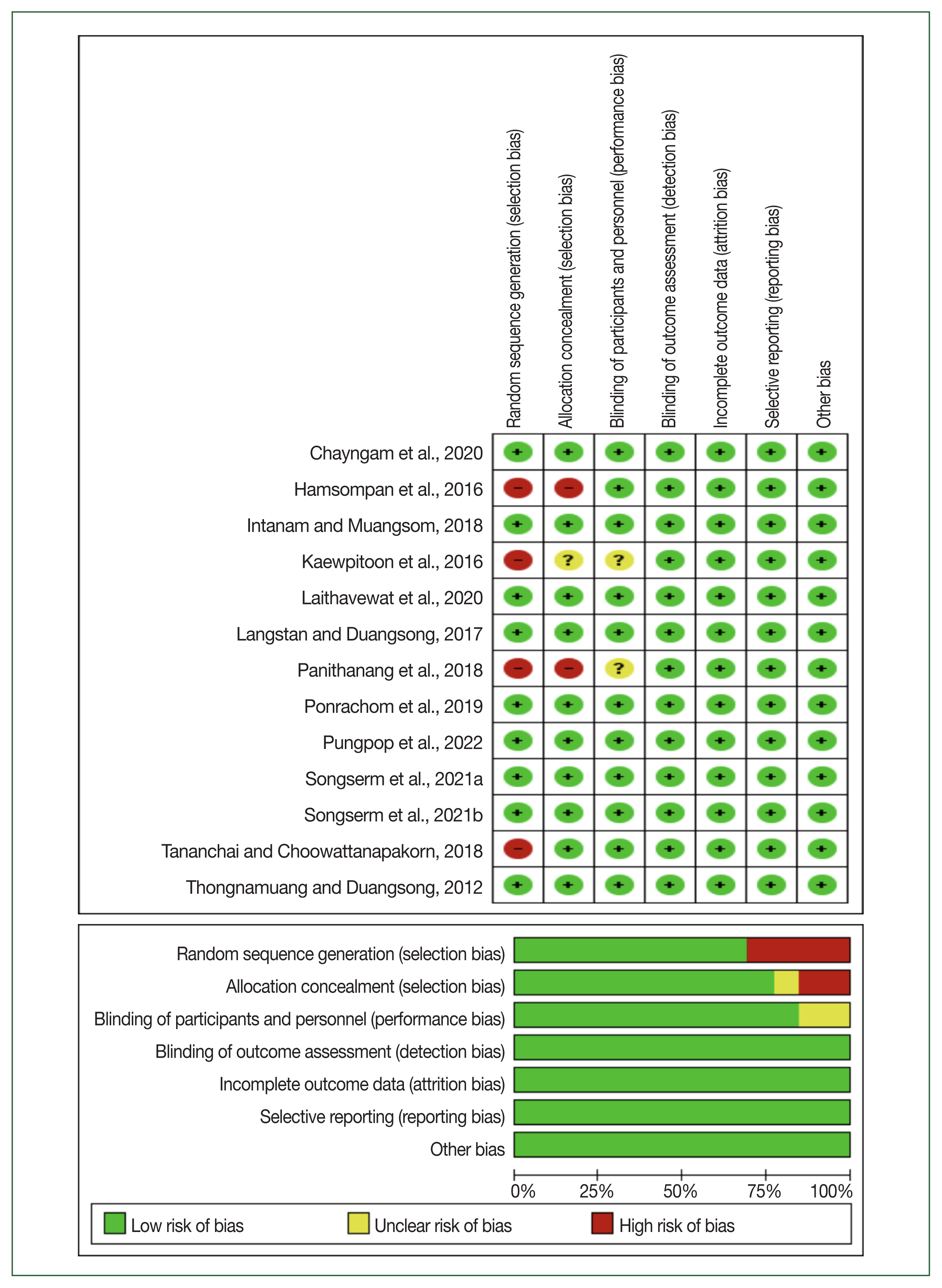

The quality of the selected studies was appraised using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias, and the results were visualized using a funnel plot in Review Manager version 5.4 (2020, The Cochrane Collaboration, London, United Kingdom). The risk of bias was evaluated in 3 categories: low, high, and unclear. For random sequence generation, 9 studies employed random sampling methods and were rated low risk. Ten studies reported allocation concealment, which is considered low risk, while 2 were rated as high risk. For blinding, 11 studies were rated as low risk, and 2 studies were rated as unclear due to insufficient information regarding participant blinding. All studies were assessed as low risk for incomplete outcome data, as the sample data were thoroughly analyzed. Selective reporting was not an issue in any of the studies, and no other biases were identified (

Fig. 2).

Data extraction followed a systematic approach, summarizing key study details such as author, country of publication, age group, sample characteristics in both experimental and comparison groups, and the study outcomes (

Table 1).

General data were synthesized to summarize key aspects of the health education programs aimed at preventing OV and CCA. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the general characteristics of the study samples. For the meta-analysis, the mean, standard deviation, and sample sizes from both the experimental and comparison groups were analyzed using Review Manager version 5.4. Cochran’s Q test and

I2 statistics were applied to assess heterogeneity across studies. Statistical significance was set at a 0.05 threshold. Heterogeneity was categorized as follows: not necessary (0%–24%), low (25%–49%), medium (50%–74%), and high (75%–100%) [

8]. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot with a significance set at 0.05.

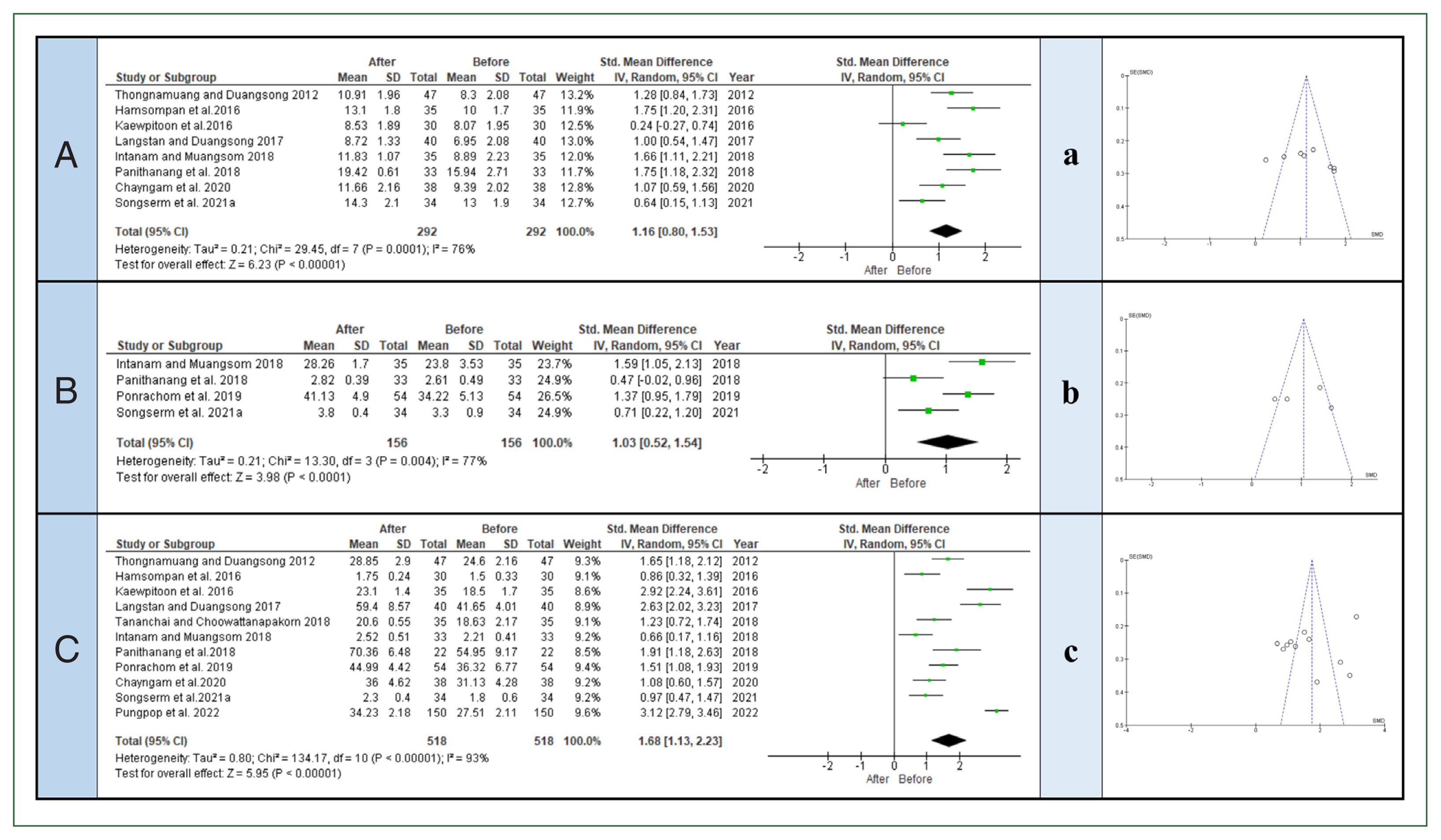

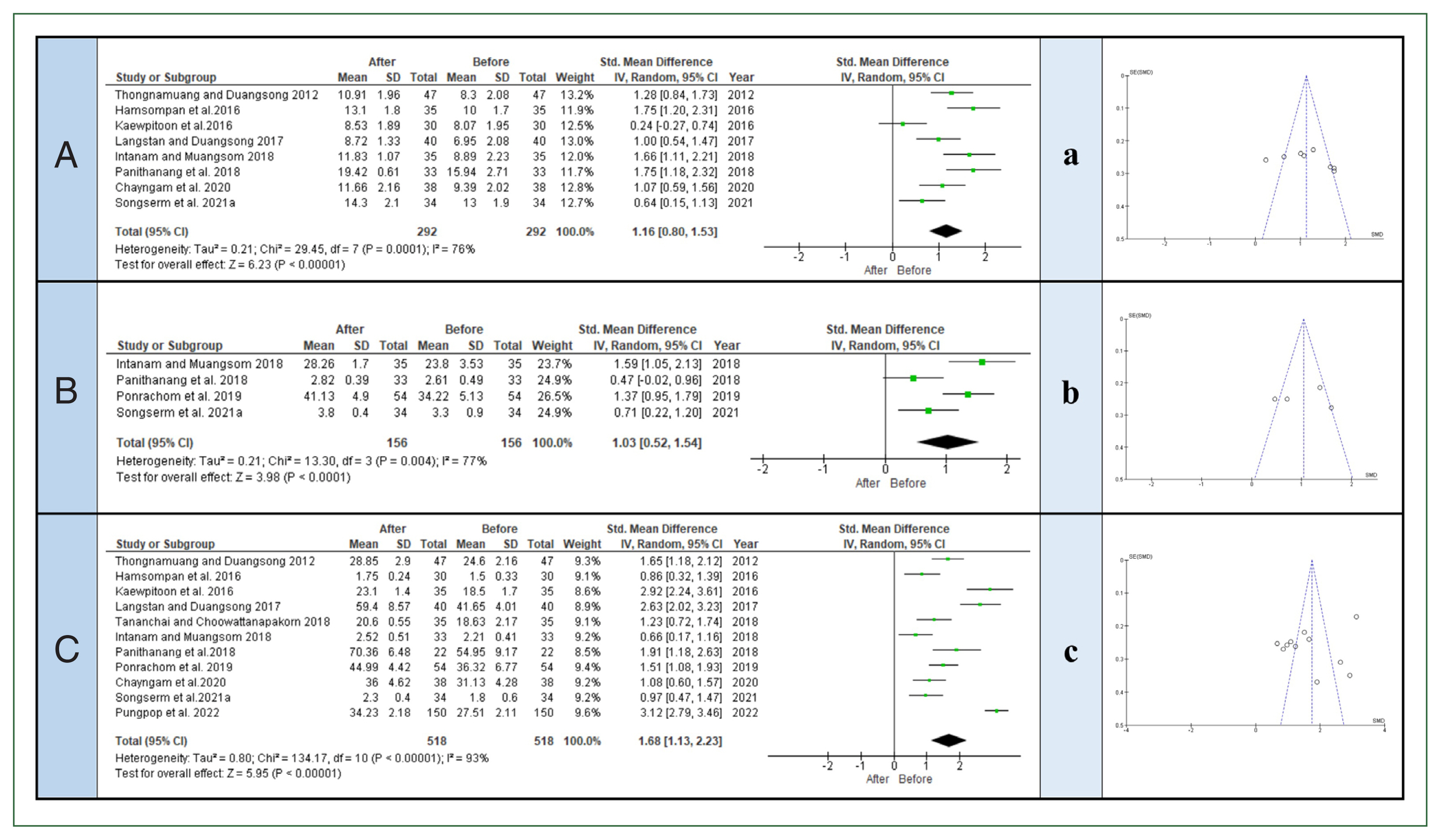

Effects of Health Education Programs on Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Behavior Modification for Preventing OV and CCA before and after the Intervention

Knowledge

The analysis of health education programs on knowledge for behavior modification to prevent OV and CCA, using the standardized mean difference (SMD), indicated high heterogeneity (

I2=76%,

P<0.001). The pooled data from 292 participants across 8 studies demonstrated a significant increase in knowledge following the intervention, with a mean difference of 1.13 (95% CI=0.96–1.31) and an

I2 value of 76% (

Fig. 3A). Subgroup analysis of knowledge outcomes after the intervention revealed an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, suggesting potential publication bias. The random-effects model confirmed high heterogeneity (

I2=76%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 3a).

The analysis of self-efficacy outcomes for behavior modification in preventing OV and CCA, using the SMD, also showed high heterogeneity (

I2=77%,

P<0.001). Based on data from 156 participants in 4 studies, self-efficacy significantly improved in participants who received the intervention, with a mean difference of 1.04 (95% CI=0.80–1.28) and an

I2 value of 77% (

Fig. 3B). Subgroup analysis revealed an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, indicating possible publication bias. A random-effects model was applied, with high heterogeneity confirmed (

I2=77%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 3b).

The analysis of behavior modification for preventing OV and CCA using SMD revealed very high heterogeneity (

I2=93%,

P<0.001). The results from 518 participants across 11 studies demonstrated a significant increase in behavior modification, with a mean difference of 1.75 (95% CI=1.60–1.90) and an

I2 value of 93% (

Fig. 3C). Subgroup analysis of behavior modification after the intervention indicated an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, suggesting a potential publication bias. The random-effects model confirmed high heterogeneity (

I2=93%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 3c).

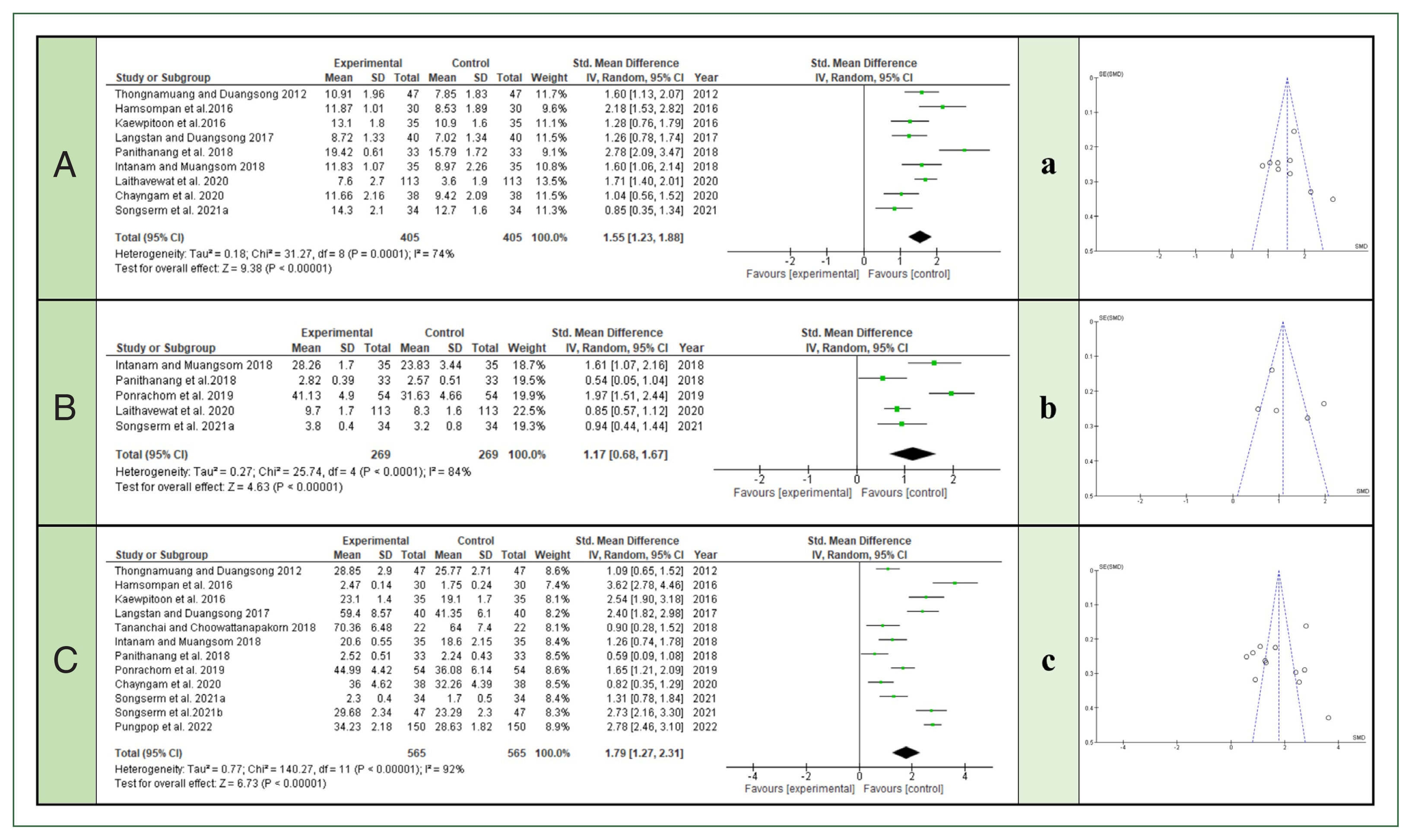

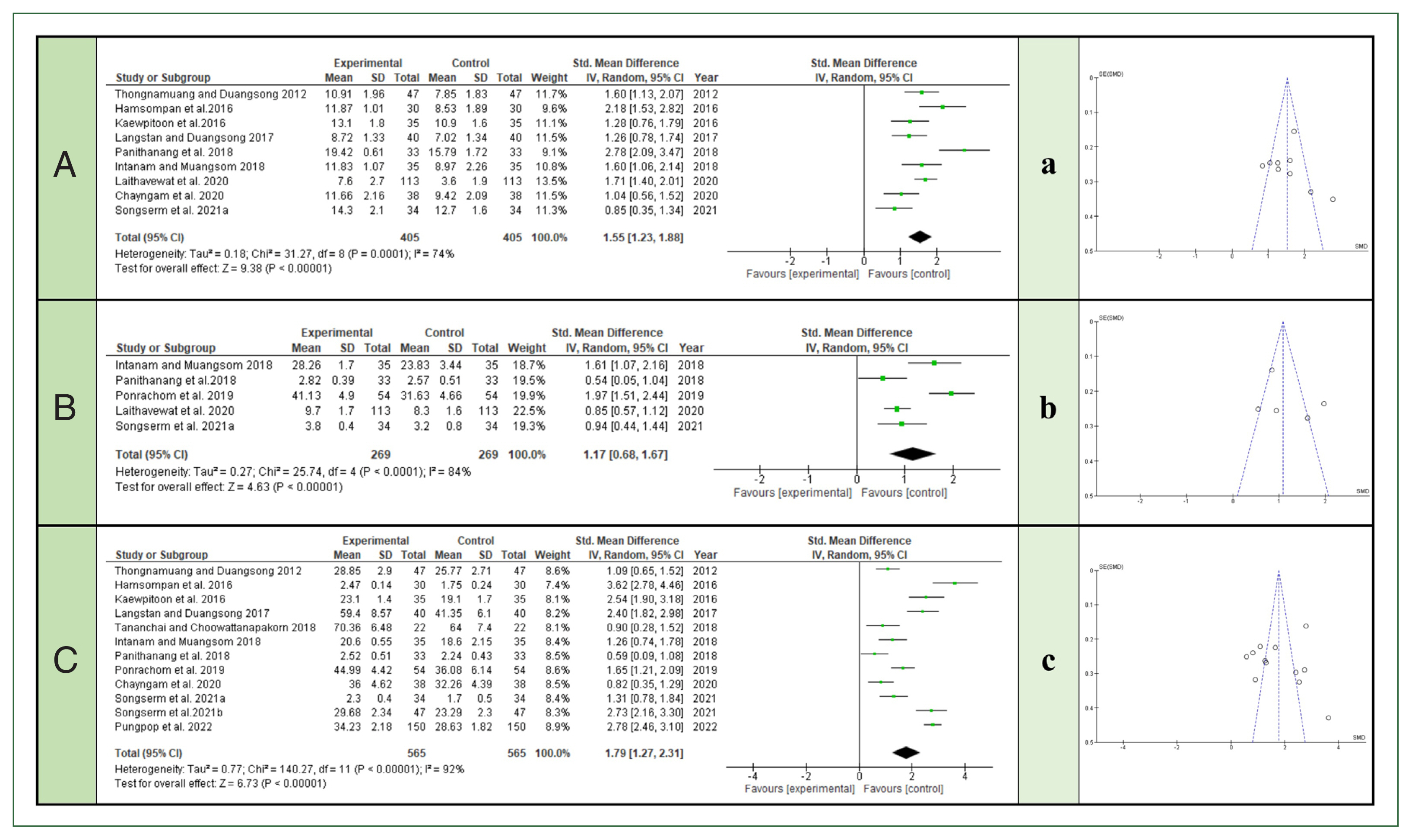

Effects of Health Education Programs on Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Behavior Modification for Preventing OV and CCA between the Experimental and Comparison Groups

Knowledge

The comparison of knowledge outcomes between experimental and comparison groups, using the SMD, revealed moderate heterogeneity (

I2=74%,

P<0.001). Analysis of data from 405 participants across 9 studies showed a significant increase in knowledge in the intervention group, with a mean difference of 1.52 (95% CI=1.36–1.68) and an

I2 value of 74% (

Fig. 4A). Subgroup analysis showed an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, indicating potential publication bias. A random-effects model confirmed medium heterogeneity (

I2=74%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 4a).

The analysis of self-efficacy outcomes between the experimental and comparison groups, using the SMD, indicated high heterogeneity (

I2=84%,

P<0.001). Data from 269 participants across 5 studies revealed a significant increase in self-efficacy in the intervention group, with a mean difference of 1.08 (95% CI=0.90–1.26) and an

I2 value of 84% (

Fig. 4B). Subgroup analysis showed an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, indicating possible publication bias. A random-effects model confirmed high heterogeneity (

I2=84%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 4b).

The analysis of behavior modification between the experimental and comparison groups, using the SMD, revealed very high heterogeneity (

I2=92%,

P<0.001). Data from 565 participants across 12 studies demonstrated a significant increase in behavior modification in the intervention group, with a mean difference of 1.78 (95% CI=1.63–1.92) and an

I2 value of 92% (

Fig. 4C). Subgroup analysis revealed an asymmetrical distribution in the funnel plot, suggesting potential publication bias. The random-effects model confirmed high heterogeneity (

I2=92%,

P<0.001) (

Fig. 4c).

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the effects of self-efficacy–based health education programs on preventing OV and CCA by enhancing knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior modification. The findings demonstrated significant improvements in these outcomes, confirming the effectiveness of such interventions. The following discussion addresses each of these issues in detail.

The results revealed a statistically significant increase in knowledge following the intervention, with the experimental group showing a higher increase than the comparison group. Before the intervention, participants generally lacked adequate knowledge about the risks of OV infection and CCA. After receiving targeted health education, which included detailed information on the causes, prevention, and consequences of OV infection, participants in the experimental group demonstrated significantly higher knowledge scores than theircomparison group counterparts (

P<0.001). These findings suggest that health education programs are crucial in improving public understanding of OV and CCA prevention. The significant improvement in knowledge can be attributed to the structured delivery of information through various educational materials, such as brochures, videos, and group discussions, which cater to different learning styles [

9–

11].

A vital intervention component was enhancing self-efficacy, which is critical in behavior change. The analysis showed a significant increase in self-efficacy scores after the intervention, with participants in the experimental group reporting greater confidence in their ability to prevent OV infection and CCA than those in the comparison group (

P<0.001). These results align with Bandura’s theory that self-efficacy influences motivation and the adoption of preventive behaviors [

5]. By reinforcing participants’ belief in their ability to avoid high-risk behaviors, such as consuming raw fish, the intervention successfully empowered them to make healthier choices. The significant increase in self-efficacy observed in this study highlights the importance of using health education strategies that build individuals’ confidence in their ability to engage in preventive health behaviors [

7,

12,

13].

The ultimate goal of the health education programs was to modify participants’ behaviors to reduce OV infection risk. The findings showed a significant improvement in behavior modification following the intervention, particularly among participants in the experimental group compared to the comparison group (

P<0.001). The observed behavior changes included a notable reduction in raw or undercooked fish consumption, increased adherence to food safety practices, and improved overall hygiene. These results indicate that self-efficacy–based health education can effectively translate increased knowledge and confidence into tangible behavior changes. The high heterogeneity in behavior modification outcomes (

I2=93%) suggests variability in participants’ responses to the intervention, possibly due to cultural differences or personal preferences. However, the consistent improvement across studies emphasizes the intervention’s effectiveness in promoting long-term preventive behaviors [

6,

9].

The comparison between the experimental and comparison groups across all 3 outcomes—knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior modification—further supports the intervention’s efficacy. The experimental group consistently outperformed the comparison group, with significant improvements in knowledge (

I2=74%,

P<0.001), self-efficacy (

I2=84%,

P<0.001), and behavior modification (

I2=92%,

P<0.001). These findings highlight the critical role of structured, theory-driven health education programs in influencing health behaviors. Notably, the experimental group exhibited higher sustained behavior changes over time, suggesting that incorporating self-efficacy principles enhances immediate outcomes and contributes to long-term behavioral adherence [

6,

14].

This meta-analysis has some limitations. High heterogeneity across the included studies, particularly in behavior modification outcomes, suggests variability in intervention effectiveness across different populations. Potential publication bias, indicated by funnel plot asymmetry, may have inflated positive results by excluding non-significant studies. Additionally, varying follow-up durations raise concerns about the long-term sustainability of behavior changes. Finally, the analysis centers on self-efficacy–based programs, potentially overlooking other critical factors influencing behavior change.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that self-efficacy–based health education programs effectively increase knowledge, enhance self-efficacy, and promote behavior modification for preventing OV and CCA. The statistically significant improvements observed in the experimental group indicate that such interventions should be integral to public health strategies in endemic areas. Future research should explore applying these educational models to other health challenges as they broadly apply to various disease prevention efforts.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Busabong W, Woradet S, Songserm N

Data curation: Busabong W

Formal analysis: Busabong W, Woradet S, Songserm N

Investigation: Busabong W

Software: Busabong W

Project administration: Woradet S, Songserm N

Supervision: Woradet S, Songserm N

Writing – original draft: Busabong W, Woradet S, Songserm N

Writing – review & editing: Busabong W, Woradet S, Songserm N

-

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University for providing the database for the search.

Fig. 1Flowchart of study selection. This figure illustrates the systematic review process, including the initial number of studies identified, the screening phases, and the criteria for exclusion, leading to the final number of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 2Risk of bias graph and summary. This figure shows the distribution of the risk of bias judgments across domains, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, outcome data, reporting, and other biases, categorized by color to indicate low, high, or unclear risk in key bias domains as per the Cochrane Collaboration tool.

Fig. 3The forest plot and funnel plot present the effects of health education programs on outcomes, respectively: (A), (a) knowledge; (B), (b) self-efficacy; and (C), (c) behavior modification for preventing Opisthorchis viverrini and cholangiocarcinoma before and after the experiment. IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 4The forest plot and funnel plot present the effects of health education programs on outcomes, respectively: (A), (a) knowledge; (B), (b) self-efficacy; and (C), (c) behavior modification for preventing Opisthorchis viverrini and cholangiocarcinoma between the experimental and comparison groups. IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1Literature reviews of health education programs for preventing Opisthorchis viverrini and cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand

Table 1

|

Reference |

Age group (year) |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Results |

|

|

|

n

|

Mean |

SD |

n

|

Mean |

SD |

|

Knowledge |

|

[9] |

10–12 |

47 |

10.91 |

1.96 |

47 |

7.85 |

1.83 |

After the experiment, the intervention group had higher knowledge than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[10] |

15–70 |

35 |

13.10 |

1.80 |

35 |

10.90 |

1.60 |

The experimental group had a mean knowledge score higher than the comparison group (mean difference=2.5, 95% CI=1.4–3.6, P<0.001). |

|

[11] |

20–50 |

30 |

11.87 |

1.01 |

30 |

8.53 |

1.89 |

After the trial, the family leaders had mean knowledge scores higher than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[15] |

40–59 |

40 |

8.72 |

1.33 |

40 |

7.02 |

1.34 |

The experimental group’s mean knowledge scores were significantly higher than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[12] |

10–12 |

35 |

11.83 |

1.07 |

35 |

8.97 |

2.26 |

After the intervention, the experimental group’s knowledge scores were higher than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[7] |

30–89 |

33 |

19.42 |

0.61 |

33 |

15.79 |

1.72 |

The experimental group had significantly greater knowledge than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[16] |

10–12 |

113 |

7.60 |

2.70 |

113 |

3.60 |

1.90 |

The intervention group had significantly greater knowledge than those in the comparison schools (P<0.05). |

|

[17] |

≥ 30 |

38 |

11.66 |

2.16 |

38 |

9.42 |

2.09 |

The experimental group knew significantly higher than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[6] |

≥ 20 |

34 |

14.30 |

2.10 |

34 |

12.70 |

1.60 |

After the experiment, the mean scores of knowledge of the experimental group were significantly higher than before the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

|

Self-efficacy |

|

[12] |

10–12 |

35 |

28.26 |

1.70 |

35 |

23.83 |

3.44 |

After the intervention, the experimental group’s perceived self-efficacy scores were higher than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[7] |

30–89 |

33 |

2.82 |

0.39 |

33 |

2.57 |

0.51 |

The experimental group had significantly greater self-efficacy than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[13] |

20–60 |

54 |

41.13 |

4.90 |

54 |

31.63 |

4.66 |

After participating in the program, the experimental group perceived self-efficacy more than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[16] |

10–12 |

113 |

9.70 |

1.70 |

113 |

8.30 |

1.60 |

The pupils in the intervention group had significantly greater self-efficacy than those in the comparison schools (P<0.05). |

|

[6] |

≥ 20 |

34 |

3.80 |

0.40 |

34 |

3.20 |

0.80 |

After the experiment, the experimental group’s perceived self-efficacy scores were significantly higher than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

|

Behavior/practice/outcome expectation |

|

[9] |

10–12 |

47 |

28.85 |

2.90 |

47 |

25.77 |

2.71 |

The experimental group’s mean practice scores were significantly higher than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[10] |

15–70 |

35 |

23.10 |

1.40 |

35 |

19.10 |

1.70 |

The experimental group had a mean practice score higher than the comparison group (mean difference=4.4, 95% CI=4.2–7.9, P<0.001). |

|

[11] |

20–50 |

30 |

2.47 |

0.14 |

30 |

1.75 |

0.24 |

The family leaders’ mean behavior scores increased than those of the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[15] |

40–59 |

40 |

59.40 |

8.57 |

40 |

41.35 |

6.10 |

The experimental group had a mean score of practice more than the comparison groups (P<0.05). |

|

[18] |

≥ 60 |

22 |

70.36 |

6.48 |

22 |

64.00 |

7.40 |

The experimental group’s mean score of complications-preventing behaviors was significantly higher than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[12] |

10–12 |

35 |

20.60 |

0.55 |

35 |

18.60 |

2.15 |

After the intervention, the scores of practice of the experimental group were higher than the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[7] |

30–89 |

33 |

2.52 |

0.51 |

33 |

2.24 |

0.43 |

The experimental group had significantly greater practice than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[13] |

20–60 |

54 |

44.99 |

4.42 |

54 |

36.08 |

6.14 |

After the program, the experimental group had better practice than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[17] |

≥ 30 |

38 |

36.00 |

4.62 |

38 |

32.26 |

4.39 |

The experimental group had proper behaviors to prevent the diseases higher than the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[6] |

≥ 20 |

34 |

2.30 |

0.40 |

34 |

1.70 |

0.50 |

The experimental group’s mean scores of prevention behavior were significantly higher than before the comparison group (P<0.05). |

|

[19] |

≥ 20 |

47 |

29.68 |

2.34 |

47 |

23.29 |

2.30 |

The mean social support score for the prevention behavior of the experimental group was significantly higher than that of the comparison group (P<0.001). |

|

[14] |

≥ 20 |

150 |

34.23 |

2.18 |

150 |

28.63 |

1.82 |

The experimental group’s mean scores of correct behaviors were significantly higher than those of the comparison group (P<0.05). |

References

- 1. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994;61:1-241.

- 2. Sripa B, Suwannatrai AT, Sayasone S, Do DT, Khieu V, et al. Current status of human liver fluke infections in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Acta Trop 2021;224:106133.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.106133

- 3. Bureau of General Communicable Diseases. Annual Report 2021 of Bureau of General Communicable Diseases. Bureau of General Communicable Diseases, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health; Nonthanuri, Thailand. 2021, pp 37-50.

- 4. Wattanawong O, Iamsirithaworn S, Kophachon T, Nak-Ai W, Wisetmora A, et al. Current status of helminthiases in Thailand: a cross-sectional, nationwide survey, 2019. Acta Trop 2021;223:106082.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.106082

- 5. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev 1977;84(2):191-215.

https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

- 6. Songserm N, Namwong W, Woradet S, Sripa B, Ali A. Public health interventions for preventing re-infection of Opisthorchis viverrini: application of the self-efficacy theory and group process in high-prevalent areas of Thailand. Trop Med Int Health 2021;26(8):962-972.

https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13598

- 7. Panithanang B, Srithongklang W, Kompor P, Pengsaa P, Kaewpitoon N, et al. The effect of health behavior modification program for liver fluke prevention among the risk group in rural communities, Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018;19(9):2673-2680.

https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.9.2673

- 8. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- 9. Thongnamuang S, Duangsong R. The effectiveness of application by health belief model and social support for preventive behavior of opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma among primary school students in Moeiwadi District, Roi-Et Province. KKU Res J 2012;12(2):80-91.

- 10. Kaewpitoon SJ, Thanapatto S, Nuathong W, Rujirakul R, Wakkuwattapong P, et al. Effectiveness of a health educational program based on self-efficacy and social support for preventing liver fluke infection in rural people of Surin Province, Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17(3):1111-1114.

https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.3.1111

- 11. Hamsompan K, Charoenpun C, Worawong C. The effects of a program to change behavior for prevention on family leader of opisthorchiasis, Tambon Ban Phang, Kaset Wisai District, Roi-Et Province. J Office DPC 7 Khon Kaen 2016;23(2):9-22.

- 12. Intanam S, Muangsom N. Effectiveness of health educational program based on health belief model, self-efficacy and social support to prevent opisthorchiasis among primary school students in Bandung District, Udonthani Province, Thailand. Thai Pharm Health Sci J 2018;13(3):150-156.

- 13. Ponrachom C, Boonchuayhanasit K, Sukolpuk M. The effectiveness of liver fluke prevention behaviors program among ordinary people in Tao-Ngoi District, Sakon Nakhon Province, Thailand. Int J Environ Rural Dev 2019;10(1):17-21.

- 14. Pungpop S, Songserm N, Raksilp M, Woradet S, Suksatan W. Effects of integration of social marketing and health belief model for preventing cholangiocarcinoma in high-risk areas of Thailand: a community intervention study. J Prim Care Community Health 2022;13:21501319221110420.

https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319221110420

- 15. Langstan P, Duangsong R. Effects of health education program with short video on behavior modification for liver fluke prevention among risk groups aged 40–59 years in Selaphum District, Roi-Et Province. J Health Educ 2017;40(2):64-74.

- 16. Laithavewat L, Grundy-Warr C, Khuntikeo N, Andrews RH, Petney TN, et al. Analysis of a school-based health education model to prevent opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma in primary school children in northeast Thailand. Glob Health Promot 2020;27(1):15-23.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975918767622

- 17. Chayngam T, Ruangjarat L, Dechan S. Effect of health education program on health belief model application with social support for behavioral change to prevent opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma of people aged 40 years over in Muangmai Sub-district, Sriboonruang District, Nong Bua Lamphu Province. J Counc Community Public Health 2020;2(3):1-15.

- 18. Tananchai R, Choowattanapakorn T. The effect of health belief modification program on complications preventing behaviors among older persons with cholangiocarcinoma undertaking percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. J Police Nurses 2018;10(2):298-307.

- 19. Songserm N, Korsura P, Woradet S, Ali A. Risk communication through health beliefs for preventing opisthorchiasis-linked cholangiocarcinoma: a community-based intervention in multicultural areas of Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2021;22(10):3181-3187.

https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.10.3181