Abstract

Phlebotomine sandflies, important vectors of leishmaniasis, were surveyed between 2020 and 2023 in 4 southern regions of Uzbekistan—Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand—where human cases have been reported. A total of 2,905 specimens were collected and identified, representing 9 species from 2 genera: Phlebotomus (P. papatasi, P. sergenti, P. longiductus, P. caucasicus, P. mongolensis, P. andrejevi, P. alexandri) and Sergentomyia (S. sogdiana, S. grecovi). Sandfly abundance was highest in Kashkadarya (43.0%, n=1,249), followed by Surkhandarya (33.7%, n=979), Jizzakh (12.7%, n=369), and Samarkand (10.6%, n=308). P. sergenti was the most frequently detected species, predominating in Jizzakh (68.8%), Samarkand (63.3%), and Surkhandarya (42.1%), while P. papatasi was also prevalent, particularly in Kashkadarya (26.4%) and Surkhandarya (38.6%). In contrast, P. longiductus, P. alexandri, and S. grecovi were detected at relatively low frequencies.. These findings provide critical baseline data on sandfly species composition and regional distribution, which are essential for developing effective surveillance and control strategies to prevent cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Uzbekistan.

-

Key words: Phlebotomine sandflies, Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) transmit leishmaniasis, a major disease affecting both humans and animals worldwide. More than 98 species of phlebotomine sandflies are known to transmit

Leishmania parasites [

1].

Leishmaniasis is a protozoan parasitic disease caused by

Leishmania species. These parasites are found in over 100 countries worldwide, with different species prevalent in different geographical regions. There are 3 main forms of leishmaniasis: visceral leishmaniasis, which is the most severe and almost always fatal without treatment; cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most common form that usually causes skin ulcers; and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which affects the mouth, nose, and throat [

2,

3].

Leishmaniasis is classified as one of the most neglected tropical diseases, primarily due to insufficient investment in research, limited access to healthcare, and the absence of effective control measures in many endemic regions. Despite affecting millions of people worldwide, it has long been overlooked in global health agendas. In recent years, however, leishmaniasis has emerged as a major public health concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where it continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality [

4,

5].

In Uzbekistan, leishmaniasis has emerged as a significant public health problem, with the number of reported cases showing an increasing trend in recent years. Both cutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis are present in the country [

6-

8]. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is currently endemic in several regions, including Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, Samarkand, and Bukhara, as well as in the Republic of Karakalpakstan [

9]. Although visceral leishmaniasis was nearly eradicated through previous control efforts, it is now re-emerging, raising concern among public health authorities [

10]. The reemergence of leishmaniasis in Uzbekistan may be linked to factors such as climate change, increased human and animal movement, changes in land use, and potential gaps in vector control programs.

To date, over 800 species of phlebotomine sandflies have been identified in various regions of the world [

11]. In Uzbekistan, 17 species from 2 genera have been recorded: 12 belonging to the genus

Phlebotomus and 5 to

Sergentomyia. Among these, the primary vectors responsible for the transmission of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis are

Phlebotomus papatasi,

P. sergenti,

P. longiductus, and

P. smirnovi [

1,

9,

12,

13].

This study was conducted in Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand of southern Uzbekistan, where leishmaniasis cases have been increasingly reported, aims to improve understanding of phlebotomine sandfly species and their distribution, providing valuable data to inform vector control strategies in Uzbekistan.

The institutional animal care and use committee approval was not required for this study because it involved only the collection of sandflies (insects) and did not include any vertebrate animals.

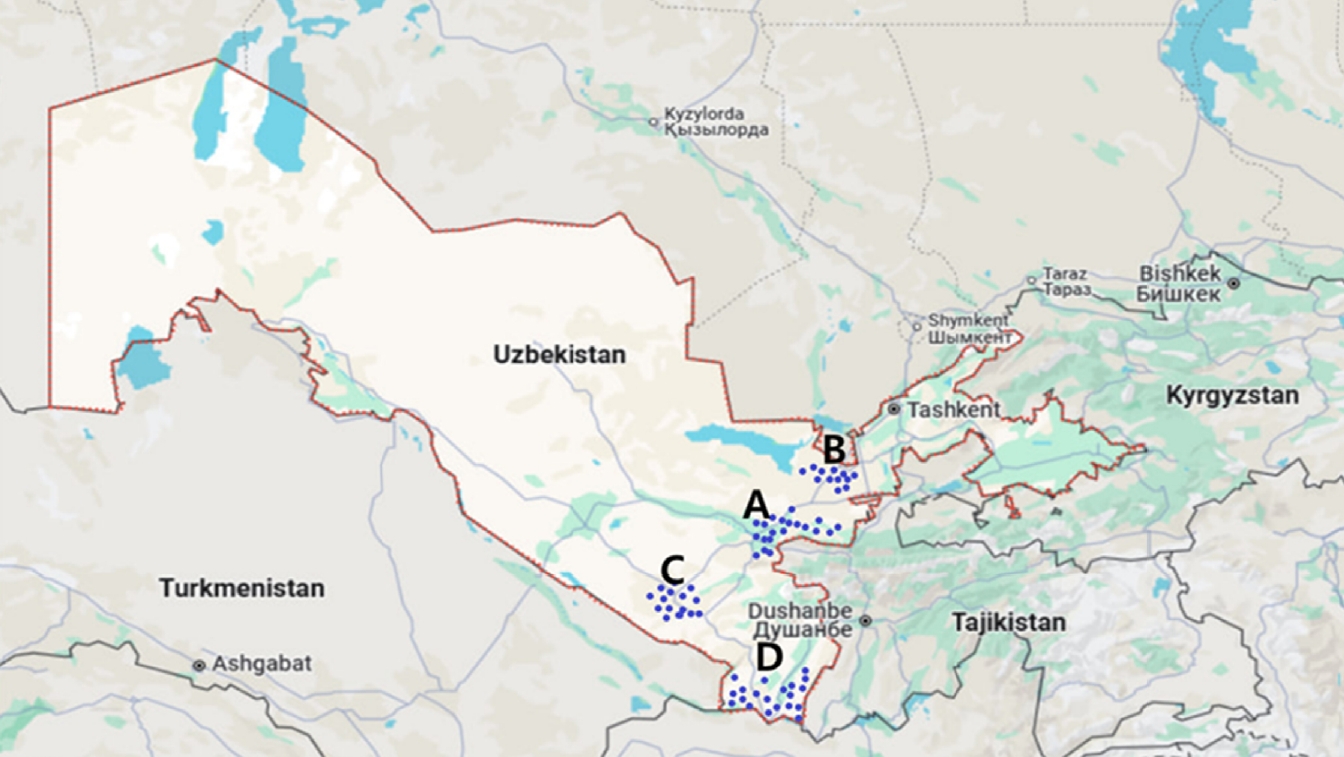

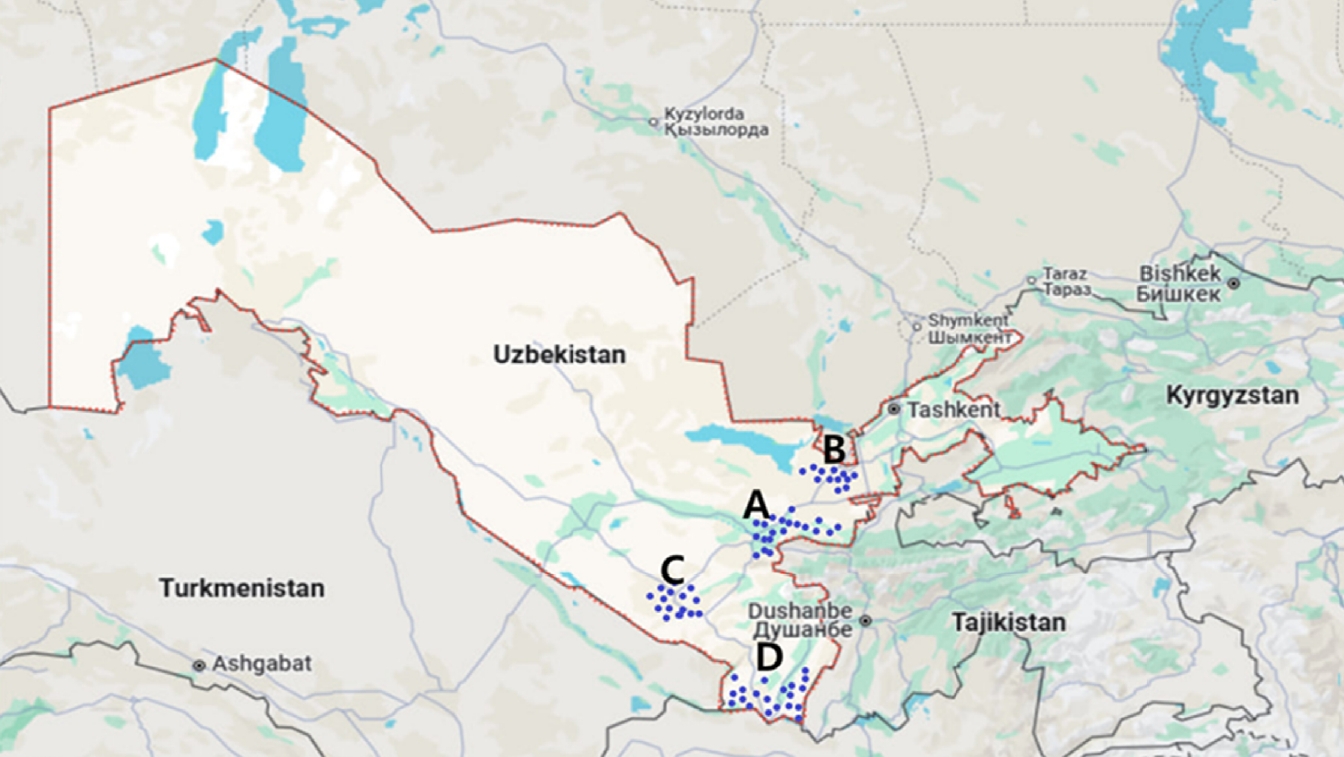

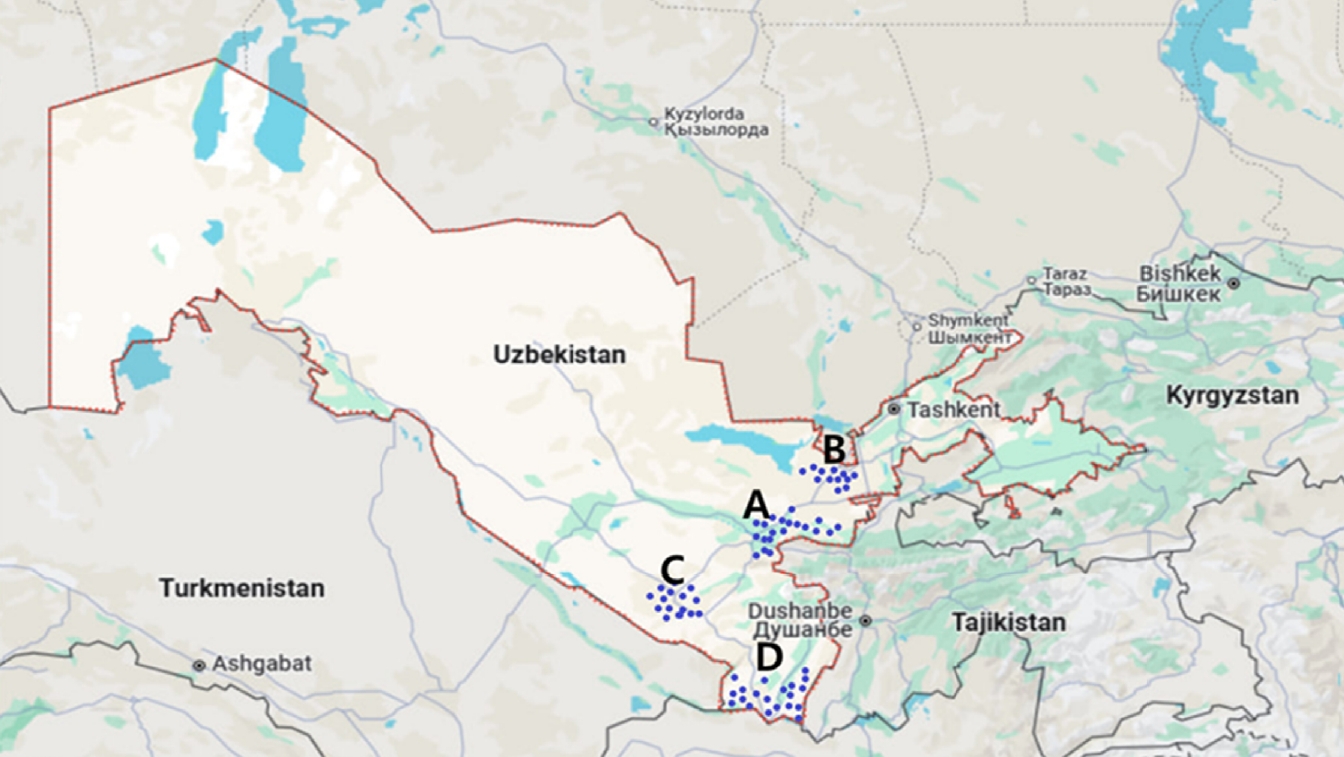

Phlebotomine sandflies were collected between 2020 and 2023 in 4 endemic regions of Uzbekistan—Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand—where autochthonous human cases have been reported (

Fig. 1). Specimens were collected using A4-sized sticky paper traps placed indoors in residential dwellings between 17:00 and 18:00 (i.e., prior to sunset) during the peak summer months of July and August. Traps were retrieved the following morning between 06:00 and 07:00.

All collected specimens were preserved in 96% ethyl alcohol solution. For species identification, permanent slides were prepared using a gum arabic-based mounting medium (Fora liquid). The specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope and identified to the species level based on morphological characteristics using standard taxonomic keys.

To investigate the species composition and geographical distribution of phlebotomine sandflies in the surveyed areas, the identified species data were statistically processed as percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 365 version 2108 (Microsoft Corporation) and R software version 4.2.2 (R Core Team).

A total of 2,905 phlebotomine sandflies were collected across 4 regions of Uzbekistan, belonging to 2 genera (

Phlebotomus and

Sergentomyia) and comprising 9 species:

P. papatasi,

P. sergenti,

P. longiductus,

P. caucasicus,

P. mongolensis,

P. andrejevi,

P. alexandri,

S. sogdiana, and

S. grecovi.

P. sergenti was the most frequently collected species, accounting for 36.7% of all specimens, followed by

P. papatasi (27.4%) and

P. andrejevi (11.6%). The remaining species were collected at lower frequencies:

P. caucasicus (4.3%),

P. alexandri (3.7%),

P. longiductus (3.0%),

P. mongolensis (2.3%),

S. grecovi (6.7%), and

S. sogdiana (4.1%) (

Table 1).

The geographical distribution of phlebotomine sandflies across 4 regions of Uzbekistan was as follows: Kashkadarya (43.0%), Surkhandarya (33.7%), Jizzakh (12.7%), and Samarkand (10.6%) (

Table 1). The relative abundance of phlebotomine sandflies varied significantly among regions (

χ2=52.38,

P<0.001), with the highest proportion in Kashkadarya (43.0%) and the lowest in Samarkand (10.6%). Species richness also differed significantly (

χ2=18.62,

P=0.002), being highest in Kashkadarya (7 species), followed by Surkhandarya (6 species), and lowest in Samarkand and Jizzakh (5 species each) (

Table 1).

In the Samarkand region, 5 species were collected at the Urgut site, with

P. sergenti being the most common species (63.3%), followed by

P. longiductus (16.9%),

P. papatasi (8.8%),

P. alexandri (7.5%), and

S. grecovi (3.5%) (

Table 1).

In the Kashkadarya region, 7 species were identified.

P. andrejevi was the most frequently collected species (27.0%), followed by

P. papatasi (26.4%),

P. sergenti (16.5%),

P. caucasicus (10.0%),

P. mongolensis (5.4%),

S. sogdiana (8.0%), and

S. grecovi (6.6%) (

Table 1).

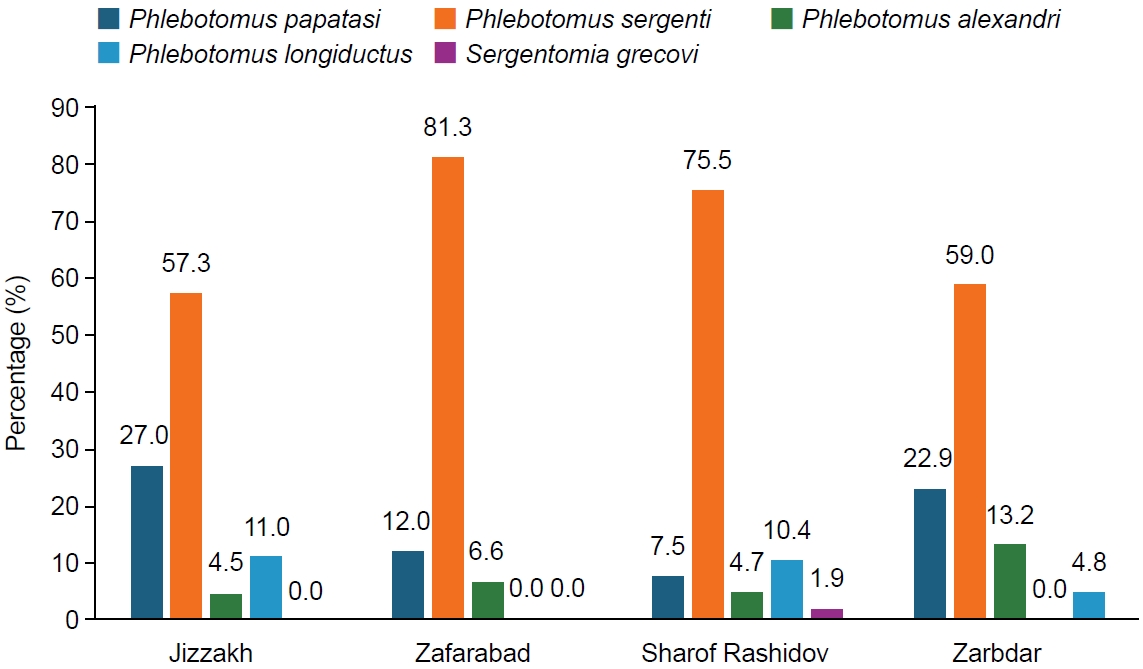

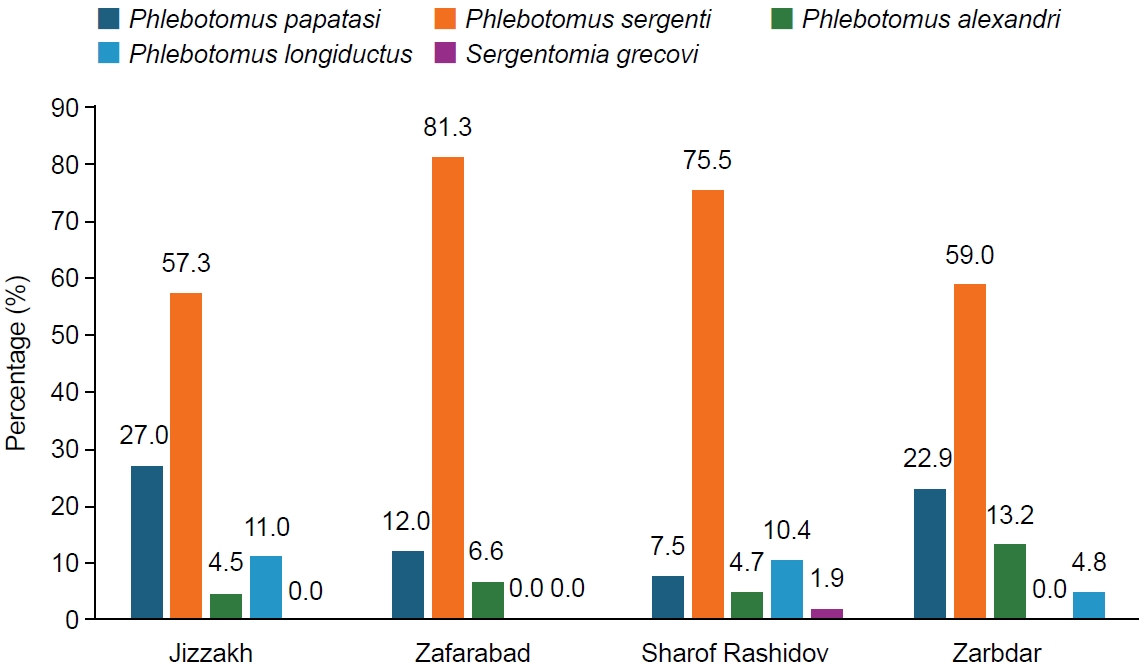

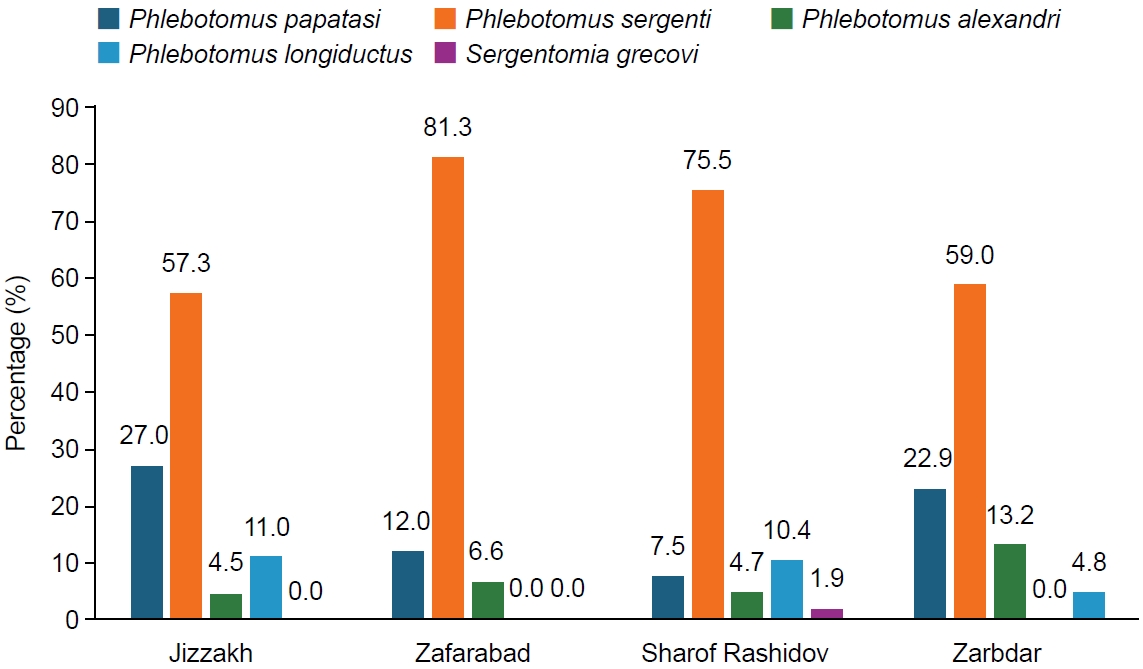

In the Jizzakh region, 5 species were collected at the sites of Jizzakh (24.2%), Zafarabad (24.6%), Sharof Rashidov (28.7%), and Zarbdar (22.5%). The most frequent species was

P. sergenti (68.8%), followed by

P. papatasi (16.8%),

P. alexandri (7.0%),

P. longiductus (5.7%), and

S. grecovi (1.6%) (

Table 1;

Fig. 2).

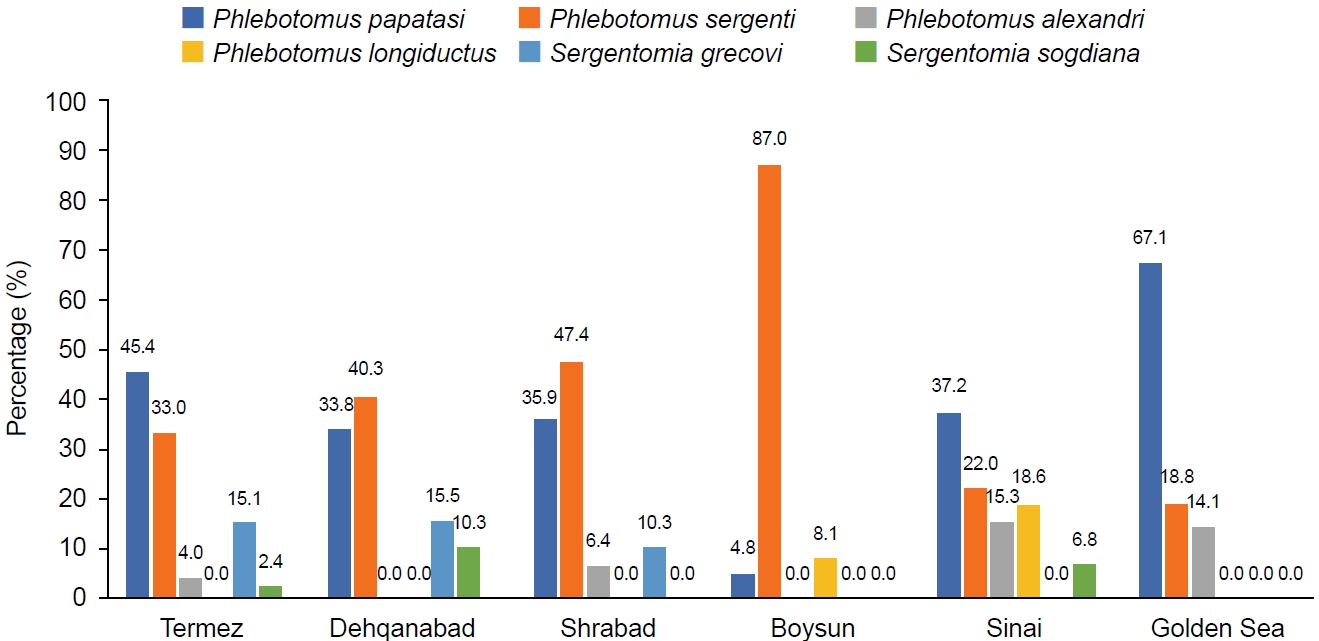

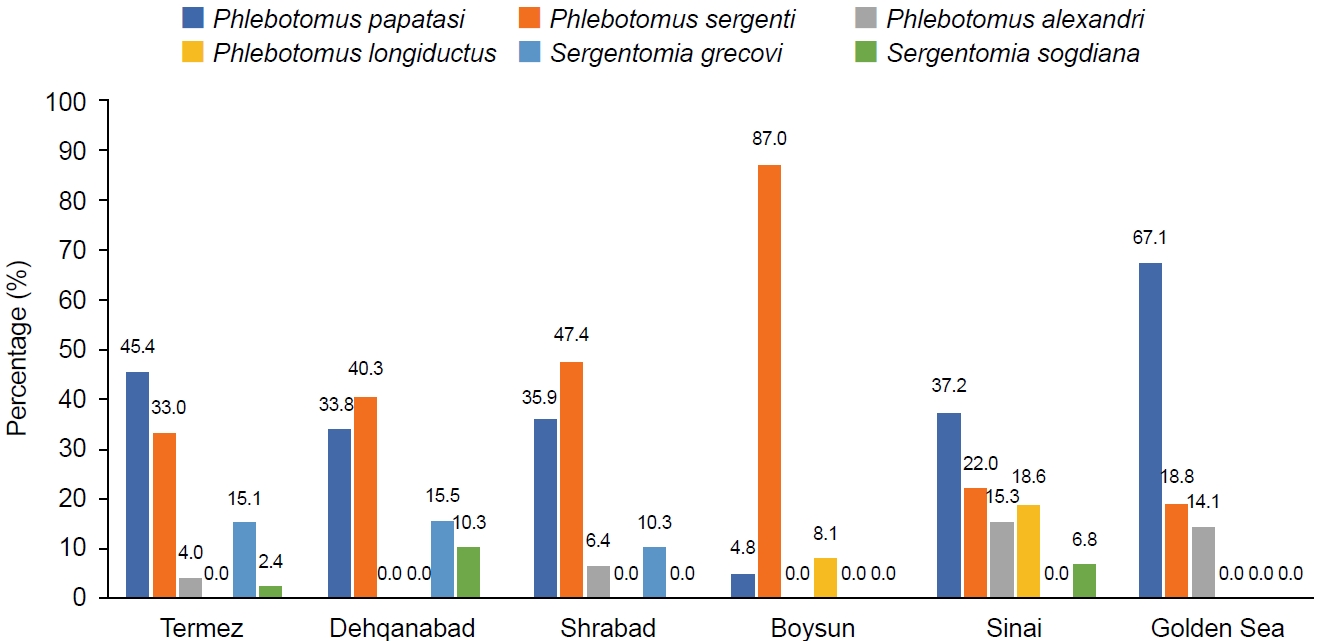

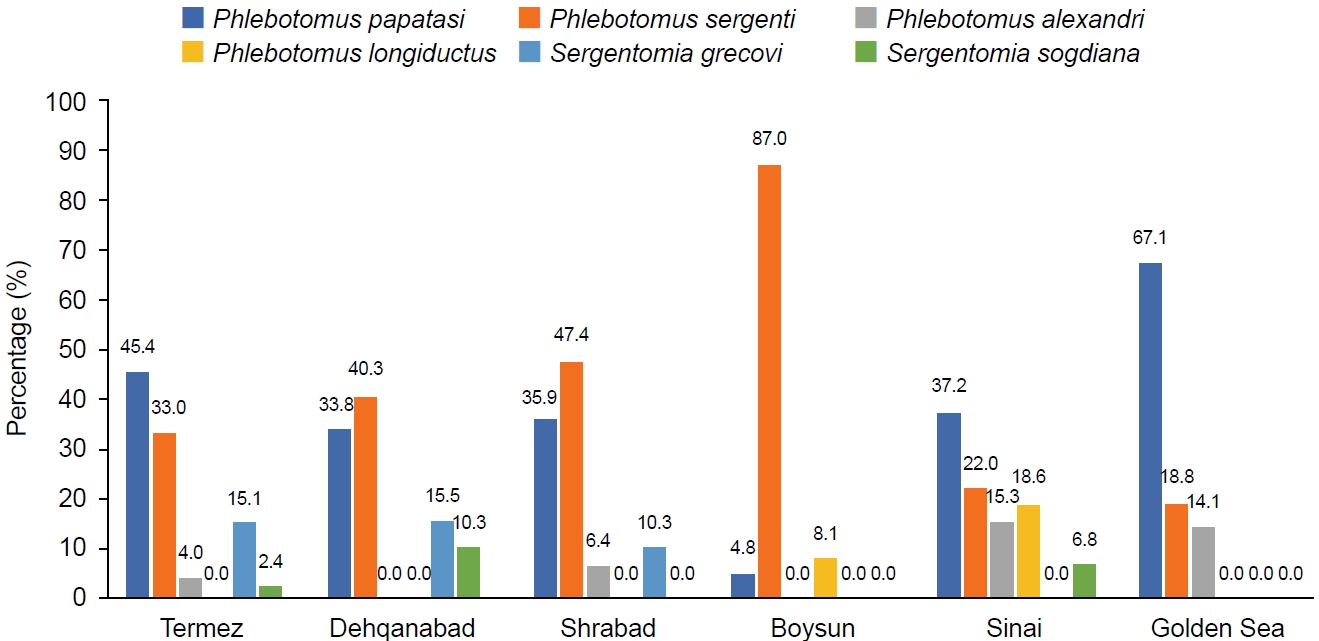

In Surkhandarya, 6 species were collected from the sites of Termez (26.0%), Dehqanabad (7.9%), Sherabad (44.9%), Boysun (6.4%), Sinai (6.0%), and Golden Sea (8.8%). The most common species was

P. sergenti (42.1%), followed by

P. papatasi (38.6%),

P. alexandri (6.0%),

P. longiductus (1.6%),

S. grecovi (9.7%), and

S. sogdiana (1.8%) (

Table 1;

Fig. 3).

Leishmaniasis remains a major public health concern in Uzbekistan, particularly in the southern regions such as Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand, where both human and canine cases have been reported. The confirmed presence of

P. papatasi,

P. sergenti, and

P. longiductus as competent vectors places approximately 1.5 million people at risk of infection [

9].

In the current survey, sandfly abundance was highest in Kashkadarya (43.0%), followed by Surkhandarya (33.7%), Jizzakh (12.7%), and Samarkand (10.6%). Species distribution showed that

P. sergenti was dominant in Jizzakh (68.8%), Samarkand (63.3%), and Surkhandarya (42.1%), while

P. papatasi was prevalent in Kashkadarya (26.4%) and Surkhandarya (38.6%). Other species such as

P. longiductus,

P. alexandri, and

Sergentomyia grecovi appeared at lower frequencies. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which reported similar distribution patterns of sandfly vectors in the same regions [

4,

9]. This survey further highlights regional variations in the distribution of

P. papatasi and

P. sergenti, the principal vectors of

Leishmania major and

L. tropica, respectively.

Recent changes in the distribution of sandfly vector in the Surkhandarya region suggest a shift in leishmaniasis transmission patterns. While

P. papatasi remains the main vector of

L. major, the proportion of

P. sergenti, the vector of

L. tropica, has risen significantly from 5.4% to 41.4%. Additionally, the Jizzakh region, previously associated with

L. tropica, has shown recent

L. major infections, indicating a shift in local epidemiology [

4]. These distribution differences are strongly influenced by regional environmental factors, climatic conditions, and traditional housing structures, with

P. papatasi being most common in riverine and oasis areas.

Other studies have also reported that the distribution and density of

P. papatasi and

P. sergenti are influenced by various environmental factors.

P. papatasi shows a correlation with nighttime temperatures, while

P. sergenti tends to have higher densities in areas with abundant vegetation [

14,

15]. Additionally,

P. papatasi is more commonly found indoors, indicating a closer association with humans, while

P. sergenti is typically found outdoors, suggesting it primarily inhabits natural environments [

16].

As shown in

Table 1, the geographical and climatic conditions of southern Uzbekistan—particularly in regions such as Kashkadarya, Surkhandarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand—play a crucial role in the distribution of sandfly vectors, including

P. papatasi and

P. sergenti. These regions, characterized by varying levels of humidity, temperature, and vegetation, create favorable environments for sandflies to thrive. Kashkadarya, with its higher humidity and abundant organic matter, supports larger populations of

P. papatasi, whereas Surkhandarya’s warmer climate favors the proliferation of

P. sergenti. Furthermore, despite their drier climates, Jizzakh and Samarkand also show high prevalence of

P. sergenti, suggesting that this species is capable of adapting to a broad range of environmental conditions.

Traditional housing structures in southern Uzbekistan, typically comprising a main residential building, livestock sheds, poultry houses, firewood storage, and outdoor toilets, are often situated close to each other. These arrangements, often combined with limited sanitation, create favorable conditions for sandfly breeding. The presence of organic matter, shaded microhabitats, and elevated humidity in these environments supports the survival and development of sandflies, which are critical vectors in the transmission of leishmaniasis. The prevalence of

Leishmania infections, particularly cutaneous and visceral forms, correlates with the abundance and distribution of these sandflies. Therefore, the natural environment and human habitation patterns in these regions significantly influence the spread of leishmaniasis, underscoring the importance of targeted public health measures to control sandfly populations and reduce disease transmission [

9,

17,

18].

This study supports previous findings, demonstrating that the surveyed regions—Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, and Samarkand—are predominantly composed of traditional rural household structures [

9,

19]. These housing and environmental conditions, including close proximity to livestock, accumulation of organic waste, and limited sanitation infrastructure, create ideal habitats for phlebotomine sandflies to thrive in peri-domestic settings. Typical rural homes in these areas often feature fruit trees, small-scale gardens, and outdoor animals such as dogs and cats. These elements, combined with open yards and the traditional architectural layout, foster microenvironments that support the development and persistence of sandfly populations. Such ecological interactions between humans, animals, and the surrounding habitat must be considered when designing effective vector control strategies.

In Uzbekistan, both cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis remain pressing public health concerns. The primary vectors, P. papatasi and P. sergenti, are intimately linked with the described environmental and domestic conditions. As such, vector control initiatives must be context-specific, addressing both ecological and sociocultural dynamics. Integrated vector management—which includes environmental modification, targeted insecticide use, and community education—offers a comprehensive approach to reducing sandfly populations and interrupting disease transmission.

Recent studies from various regions of Uzbekistan have revealed notable shifts in the epidemiology of leishmaniasis. In the Jizzakh region, the detection of

L. major in 2019 suggests a transition from anthroponotic to zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Similar trends were observed in the Urgut district, where

P. sergenti and

P. longiductus were identified as the main vectors associated with zoonotic transmission [

18].

In the Surxondaryo region, a study conducted in 2021–2022 reported a sharp increase in the proportion of

P. sergenti from 5.4% to 41.4%, while

P. alexandri and

P. longiductus were newly recognized as potential vectors of visceral leishmaniasis [

4]. These changes in vector distribution appear to correlate with the rising incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis, underscoring the pivotal role of vector dynamics in shaping disease patterns.

Furthermore, findings from the Bukhara region in 2022 confirmed

L. major infections in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis, providing additional evidence of a shift from anthroponotic to zoonotic transmission [

20]. Collectively, these observations suggest that vector composition and ecological changes are driving a gradual epidemiological transition of leishmaniasis in Uzbekistan.

Future research should prioritize understanding the ecological behavior of P. papatasi and P. sergenti, especially under conditions of environmental and climatic change. In addition, investigating the role of domestic animals as potential reservoirs, the influence of housing quality, and human behavioral risk factors will provide deeper insights into transmission dynamics. Moreover, evaluating the effectiveness and adaptability of current integrated vector management strategies across diverse ecological settings is essential to optimize their impact.

Given the possibility of sandfly species adapting to new environments under changing climate conditions, proactive surveillance is essential. Variations in temperature, humidity, and the availability of organic matter can significantly alter vector composition and abundance. Additionally, identifying other potential sandfly-borne pathogens is critical to assessing broader public health risks.

In conclusion, the effective and sustainable control of sandfly populations and mitigation of leishmaniasis transmission in Uzbekistan require a nuanced understanding of rural ecosystems, targeted vector management, and adaptive public health strategies that reflect the complex interplay between environmental, biological, and social factors.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Usarov GX. Data curation: Usarov GX, Lee IY, Sattarova XG. Formal analysis: Usarov GX, Sattarova XG. Funding acquisition: Yong TS. Investigation: Usarov GX, Turitsin VS, Xalikov QM. Resources: Turitsin VS, Xalikov QM. Supervision: Yong TS. Visualization: Usarov GX, Lee IY. Writing - original draft: Usarov GX, Turitsin VS, Xalikov QM, Sim S, Yong TS, Lee IY, Sattarova XG. Writing - review & editing: Usarov GX, Turitsin VS, Xalikov QM, Sim S, Yong TS, Lee IY, Sattarova XG.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This study was supported by PMC Service for Strengthening Capacity in Response to Infectious Diseases to Reduce the Burden of Disease in Uzbekistan (P2024-00017-1, P2014-00076-1).

Fig. 1.Map depicting the collection sites of phlebotomine sandflies in the Samarkand (A), Jizzakh (B), Kashkadarya (C), and Surkhandarya (D) regions of southern Uzbekistan.

Fig. 2.Species composition and number of phlebotomine sandflies (n, % of total and per collection site) collected using sticky traps in the Zafarabad, Sharof Rashidov, and Zarbdar districts of the Jizzakh region.

Fig. 3.Species composition and number of phlebotomine sandflies (n, % of total and per collection site) collected using sticky traps in the Termez, Dehqanabad, Shrabad, Boysun, Sinai, and Golden Sea of the Surkhandarya region.

Table 1.Relative abundance of phlebotomine sandflies in 4 regions of southern Uzbekistan during July and August from 2020 to 2023

Table 1.

|

Species |

Samarkand |

Jizzakh |

Kashkadaya |

Surkhandarya |

Total |

|

Phlebotomus papatasi

|

27 (8.8) |

62 (16.8) |

330 (26.4) |

378 (38.6) |

797 (27.4) |

|

Phlebotomus sergenti

|

195 (63.3) |

254 (68.8) |

206 (16.5) |

413 (42.1) |

1,068 (36.7) |

|

Phlebotomus longiductus

|

52 (16.9) |

21 (5.7) |

0 (0.0) |

16 (1.6) |

89 (3.0) |

|

Phlebotomus caucasicus

|

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

125 (10.0) |

0 (0.0) |

125 (4.3) |

|

Phlebotomus mongolensis

|

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

68 (5.4) |

0 (0.0) |

68 (2.3) |

|

Phlebotomus andrejevi

|

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

338 (27.0) |

0 (0.0) |

338 (11.6) |

|

Phlebotomus alexandri

|

23 (7.5) |

26 (7.0) |

0 (0.0) |

59 (6.0) |

108 (3.7) |

|

Sergentomia sogdiana

|

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

100 (8.0) |

18 (1.8) |

118 (4.1) |

|

Sergentomia grecovi

|

11 (3.5) |

6 (1.6) |

82 (6.6) |

95 (9.7) |

194 (6.7) |

|

Total |

308 (10.6) |

369 (12.7) |

1,249 (43.0) |

979 (33.7) |

2,905 (100) |

References

- 1. Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol 2013;27:123-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x

- 2. Cecílio P, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Oliveira F. Sand flies: basic information on the vectors of leishmaniasis and their interactions with Leishmania parasites. Commun Biol 2022;5:305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03240-z

- 3. World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis [Internet]. 2025. [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- 4. Usarov GX, Turitsin VS, Sattarova XG, et al. Phlebotomine sand fly (Diptera: Phlebotominae) diversity in the foci of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Surxondaryo Region of Uzbekistan: 50 years on. Parasitol Res 2024;123:170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-024-08191-4

- 5. Kostygov AY, Albanaz ATS, Butenko A, et al. Phylogenetic framework to explore trait evolution in Trypanosomatidae. Trends Parasitol 2024;40:96-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2023.11.009

- 6. Strelkova MV, Ponirovsky EN, Morozov EN, et al. A narrative review of visceral leishmaniasis in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, the Crimean Peninsula and Southern Russia. Parasit Vectors 2015;8:330. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0925-z

- 7. Mann S, Frasca K, Scherrer S, et al. A review of leishmaniasis: current knowledge and future directions. Curr Trop Med Rep 2021;8:121-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-021-00232-7

- 8. Zhirenkina EN, Ponirovskiĭ EN, Strelkova MV, et al. The epidemiological features of visceral leishmaniasis, revealed on examination of children by polymerase chain reaction, in the Papsky District, Namangan Region, Uzbekistan. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2011;3:37-41.

- 9. Usarov GX, Sattarova HG, Kim OV, Murtazoeva NK, Xalimova SA. Species composition and population of mosquitoes in the scenes of curmal leishmaniasis in Uzbekistan. Int J Genet Eng 2023;11:35-6. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijge.20231103.02

- 10. Kovalenko DA, Razakov SA, Ponirovsky EN, et al. Canine leishmaniosis and its relationship to human visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Uzbekistan. Parasit Vectors 2011;4:58.

- 11. Shimabukureo PHF, de Andrade AJ, Galati EAB. Checklist of American sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae): genera, species, and their distribution. Zookeys 2017;660:67-106. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.660.10508

- 12. Boubidi SC, Benallal K, Boudrissa A, et al. Phlebotomus sergenti (Parrot, 1917) identified as Leishmania killicki host in Ghardaia, south Algeria. Microbes Infect 2011;13:691-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2011.02.008

- 13. Tabbabi A, Bousslimi N, Rhim A, Aoun K, Bouratbine A. First report on natural infection of Phlebotomus sergenti with Leishmania promastigotes in the cutaneous leishmaniasis focus in south-eastern Tunisia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;85:646-7. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0681

- 14. Boussaa S, Kahime K, Samy AM, Salem AB, Boumezzough A. Species composition of sand flies and bionomics of Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti (Diptera: Psychodidae) in cutaneous leishmaniasis endemic foci, Morocco. Parasit Vectors 2016;9:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1343-6

- 15. Kahime K, Boussaa S, El Mzabi A, Boumezzough A. Spatial relations among environmental factors and phlebotomine sand fly populations (Diptera: Psychodidae) in central and southern Morocco. J Vector Ecol 2015;40:342-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvec.12173

- 16. Doha SA, Samy AM. Bionomics of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the province of Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2010;105:850-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02762010000700002

- 17. Calderon-Anyosa R, Galvez-Petzoldt C, Garcia PJ, Carcamo CP. Housing characteristics and leishmaniasis: a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;99:1547-54. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.18-0037

- 18. Suvonkulov UT, Achilova OD, Muratov TI, et al. Etiology of skin Leishmaniosis in of endemic regions of Uzbekistan on the example of Dzhizak region. Epidemiol Infect Dis 2019;24:123-7. https://doi.org/10.18821/1560-9529-2019-24-3-123-127

- 19. Usarov X, Turistin S, Narzullayev M. Analysis of the species composition of mosquitoes in the foci of Leishmaniasis in the Urgut district of the Samarkand region. Int J Health Syst Med Sci 2024;3:297-302. https://doi.org/10.51699/ijhsms.v3i3.81

- 20. Akhmedovich MF, Samadovna SG. Statistical analysis of skin leishmaniasis in Bukhara region by age, gender and region. JournalNX 2022;8:28-31. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D3EH5

, Vladimir S. Turitsin2,3

, Vladimir S. Turitsin2,3 , Qaxor M. Xalikov1

, Qaxor M. Xalikov1 , Seobo Sim4

, Seobo Sim4 , Tai-Soon Yong5

, Tai-Soon Yong5 , In Yong Lee5,*

, In Yong Lee5,* , Xulkar G. Sattarova1,2,*

, Xulkar G. Sattarova1,2,*