Abstract

Naegleria fowleri is a free-living amoeba that can cause primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a very serious infection of the central nervous system. Early diagnosis of PAM is challenging, and the condition is almost always fatal. In this study, we conducted 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) analysis using N. fowleri trophozoite lysates and conditioned media to identify preferentially secreted proteins. As a result of the 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis, 1 protein was found to increase, 5 proteins were found to decrease, 3 proteins showed a qualitative increase, and 15 proteins showed a qualitative decrease in the conditioned media compared to the proteins in the trophozoite lysates. Using cDNA from N. fowleri, Acanthamoeba castellanii, and Balamuthia mandrillaris, all of which can cause encephalitis, real-time PCR was performed on 5 genes corresponding to the p23-like domain-containing protein, cystatin-like domain-containing protein, fowlerpain-2, hemerythrin family non-heme iron protein, and an uncharacterized protein. The results showed that all 5 genes were highly expressed in N. fowleri. In animal models infected with N. fowleri resulting in PAM, real-time PCR analysis of brain tissue revealed significant overexpression of the p23-like domain-containing protein and fowlerpain-2. These results suggest that the 2 secreted proteins could provide valuable insights for developing antibody-based or molecular diagnostic methods to detect N. fowleri in patients with PAM.

-

Key words: Naegleria fowleri, primary amebic meningoencephalitis, secreted protein

Introduction

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a rare but deadly disease caused by an infection with

Naegleria fowleri in the human body [

1,

2].

N. fowleri are free-living amoebae that inhabit warm freshwater environments such as hot springs, ponds, rivers, and lakes [

3].

Naegleria infection can occur through activities such as swimming in freshwater, washing the nasal cavity with unsterilized water, or, in rare cases, using recreational waters such as poorly managed swimming pools and surf parks [

4,

5]. Generally,

N. fowleri is introduced through the nasal cavity, travels through the olfactory nerve to the brain, and destroys central nervous system tissues. Symptoms often develop within 24 h to 1 week of infection, frequently leading to death [

6,

7]. Due to global warming, the risk of infection is increasing worldwide as the environments where

N. fowleri can thrive are expanding [

8]. Currently, there is no definitive treatment, and the clinical symptoms of PAM and bacterial meningitis are very similar, complicating rapid and accurate treatment [

9]. PAM was first reported in the 1960s, and its incidence rate has been gradually increasing [

10]. Therefore, it is crucial to quickly and accurately diagnose this deadly disease at an early stage.

Currently, PAM diagnosis is performed using CT or MRI to identify brain lesions such as diffuse cerebral edema, followed by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection for microscopic examination. This examination uses Wright-Giemsa stain, hematoxylin and eosin stain, and periodic acid-Schiff stain, or involves culturing CSF and brain tissue [

11]. Additionally, real-time PCR or PCR is used to diagnose

N. fowleri infection in CSF samples [

12,

13]. However, these methods require specialized expertise and equipment and are time-consuming, making early diagnosis challenging [

14,

15]. Therefore, there is a need for a diagnostic method that is quick, accurate, and easy to perform.

Several studies have focused on secreted proteins as targets for vaccine development, treatment, and diagnosis of amoeba infections. One study compared protein expression profiles between axenically cultured low-virulence amoebae and mouse-passaged high-virulence amoebae using 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify potential therapeutic targets for limiting PAM. Proteins such as RhoA signaling-related proteins, heat shock protein 70, and Mp2CL5 were found to be associated with high virulence, suggesting that the pathogenicity of

N. fowleri involves multiple proteins that facilitate host cell invasion [

16]. In another study, proteins related to pathogenicity among

N. fowleri excretory–secretory proteins were identified. Proteins were separated by 2-DE and reacted with

N. fowleri infection or immune sera to identify immunodominant excretory–secretory proteins, leading to the identification of 6 proteins expected to play important roles in the pathogenicity of

N. fowleri [

17]. Another study analyzed the electrophoretic patterns of membrane proteins from

N. fowleri and compared them with those from

N. lovaniensis and

N. gruberi, which are known to be nonpathogenic

Naegleria species. This study aimed to identify a membrane protein, Nf23, that may be involved in the virulence of

N. fowleri [

18]. In another study, extracellular vesicles secreted by

N. fowleri were reported to act as pathogenic factors that trigger host inflammatory responses [

19]. However, research on the development of antibodies preferentially expressed in

N. fowleri for its detection remains limited.

In this study, we investigated secreted proteins of N. fowleri that could be useful for producing antibodies capable of preferentially detecting N. fowleri. To achieve this, we compared the proteins present in the lysate of N. fowleri trophozoites with those in the cell-conditioned media using 2-DE analysis to identify proteins secreted by N. fowleri. We then confirmed the gene expression of those proteins using real-time PCR.

Methods

Ethics statement

All experiments involving animals were conducted in adherence to the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. The study was approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval No. KHSASP-24-681).

Cell cultures

N. fowleri (ATCC 30894), Acanthamoeba castellanii (ATCC 30868), and Balamuthia mandrillaris (ATCC 50209) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Vero cells were sourced from the Korean Cell Line Bank. N. fowleri were axenically cultured in Nelson’s medium (4 mg/L MgSO4•7H2O, 4 mg/L CaCl2•2H2O, 142 mg/L Na2HPO4, 136 mg/L KH2PO4, 120 mg/L NaCl, 1.7 g/L liver infusion, and 1.7 g/L glucose) at 37°C. A. castellanii were cultured in peptone-yeast-glucose medium (20 g/L proteose peptone, 1 g/L yeast extract, 0.1 M glucose, 4 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 3.4 mM sodium citrate, 0.05 mM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 2.5 mM Na2HPO4, and 2.5 mM KH2PO4) at 25°C. Vero cell were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (WelGENE) with 10% fetal bovine serum (GenDEPOT) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. When the Vero cell monolayer reached approximately 80% confluency, the culture supernatant was carefully aspirated, and B. mandrillaris was inoculated onto the monolayer along with fresh culture medium.

Sample preparation and 2-DE analysis

N. fowleri trophozoites were detached from the culture flask and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min. Protein extracts were prepared by lysing samples in a denaturing buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 2.5% DTT, and protease inhibitors), followed by homogenization and clarification through centrifugation at 15,000 g for 20 min. Conditioned media from N. fowleri were collected after 7 days of cultivation and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Unit (Merck KGaA) at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Protein concentration was measured using Bradford assay. For 2-DE, 600 µg of each sample was applied to pH 4-7 immobilized pH gradient strips (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), focused using an IPGphor III system, and then separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were fixed in 40% methanol containing 5% phosphoric acid, stained with Colloidal Coomassie Blue G-250, destained in water, and scanned for imaging. Spot detection and matching (with at least 25 landmarks per gel) were performed with ImageMaster 2D Platinum software (Amersham Biosciences).

LC-MS/MS for protein analysis

Protein spots from SDS-PAGE gels were excised and cut into pieces. These gel pieces were washed for 1 h in a solution of 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 50% acetonitrile. After dehydration in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator for 10 min, gel pieces were rehydrated in 50 ng of sequencing-grade trypsin solution (Promega). Following an overnight incubation at 37°C in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, the tryptic peptides were extracted with 5 μl of 0.5% formic acid with 50% acetonitrile for 40 min under mild sonication. The extracted solution was concentrated using a centrifugal vacuum concentrator.

LC-MS/MS analysis was conducted using an agilent 1100 series nano-LC coupled with an LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron). Peptides were separated on a 150 mm × 75 μm Magic C18 capillary column (Proxeon). The mobile phase for liquid chromatography consisted of 2 solutions: mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. A linear gradient was applied, starting from 6% to 50% of mobile phase B over 22 min, then ramping to 95% B over 5 min, before returning to 6% B over the next 13 min.

For tandem mass spectrometry, mass spectra were acquired using data-dependent acquisition with a full mass scan range of 350–1,800 m/z followed by MS/MS of the top precursors (1 microscan, normalized collision energy 35%). The ion transfer tube was set at 200°C, and the spray voltage was between 1.5 and 2.0 kV. Raw spectra were processed using SEQUEST (Thermo Quest) and searched against an in-house database using MASCOT (Matrix Science Ltd.). The MS analyses included modifications of methionine oxidation, cysteine alkylation, arginine methylation, and serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation. The peptide mass tolerance was set at 10 ppm with an MS/MS ion mass tolerance of 0.8 Da. An allowance for 1 missed cleavage was given, and charge states +2 and +3 were considered during data analysis. MS/MS spectra underwent further de novo sequencing using the PepNovo software (open source, available at

http://proteomics.ucsd.edu/Software/PepNovo.html), followed by MS-BLAST validation. All procedures were conducted with the assistance of Protia and were performed exactly as detailed in our previous publication [

20].

The expression of the 5 selected target genes was analyzed by real-time PCR, using 18S rDNA as the internal control. Total RNA from

N. fowleri,

A. castellanii, and

B. mandrillaris was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas), following the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was performed on a Magnetic Induction Cycler PCR system (PhileKorea) according to a previously established protocol [

21]: pre-incubation at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. All reaction mixtures were prepared using Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs), with specific primers listed in

Table 1. The relative expression levels were calculated by normalizing the critical threshold (Ct) values to that of the internal control (18S rDNA), and graphs were presented using the 2^-ΔCt method.

A total of 8 3-week-old female Balb/c mice were purchased from NARA Biotech. After a 1-week acclimation period, they were divided into a control group (n=4) and an infected group (n=4). Dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered intraperitoneally to the infected group at a dose of 5 mg/kg once daily for 4 consecutive days. Mice were then intranasally infected with 1×105 N. fowleri trophozoites in 50 µl PBS. They were monitored daily for clinical signs and mortality following N. fowleri infection.

Brains were collected from mice that either died or showed severe clinical deterioration, such as ruffled fur and marked reduction in mobility, following infection. Brains were also collected from control group mice. The brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Yakuri Pure Chemicals) for 24 h, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (Duksan Pure Chemicals), and subsequently embedded in OCT compound (Sigma-Aldrich), then stored at -80℃ until use.

Gene expression analysis of brain tissues by real-time PCR

Brains were sliced to a depth of 20 μm using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems). RNA was extracted from the brain tissues using the RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas), following the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was performed as described above, using specific primers (

Table 1). The relative expression levels were calculated by normalizing the Ct values to that of the control, and graphs were presented using the 2^-ΔCt method.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Data are presented as mean±SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using Student t-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant and are denoted by asterisks (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

Results

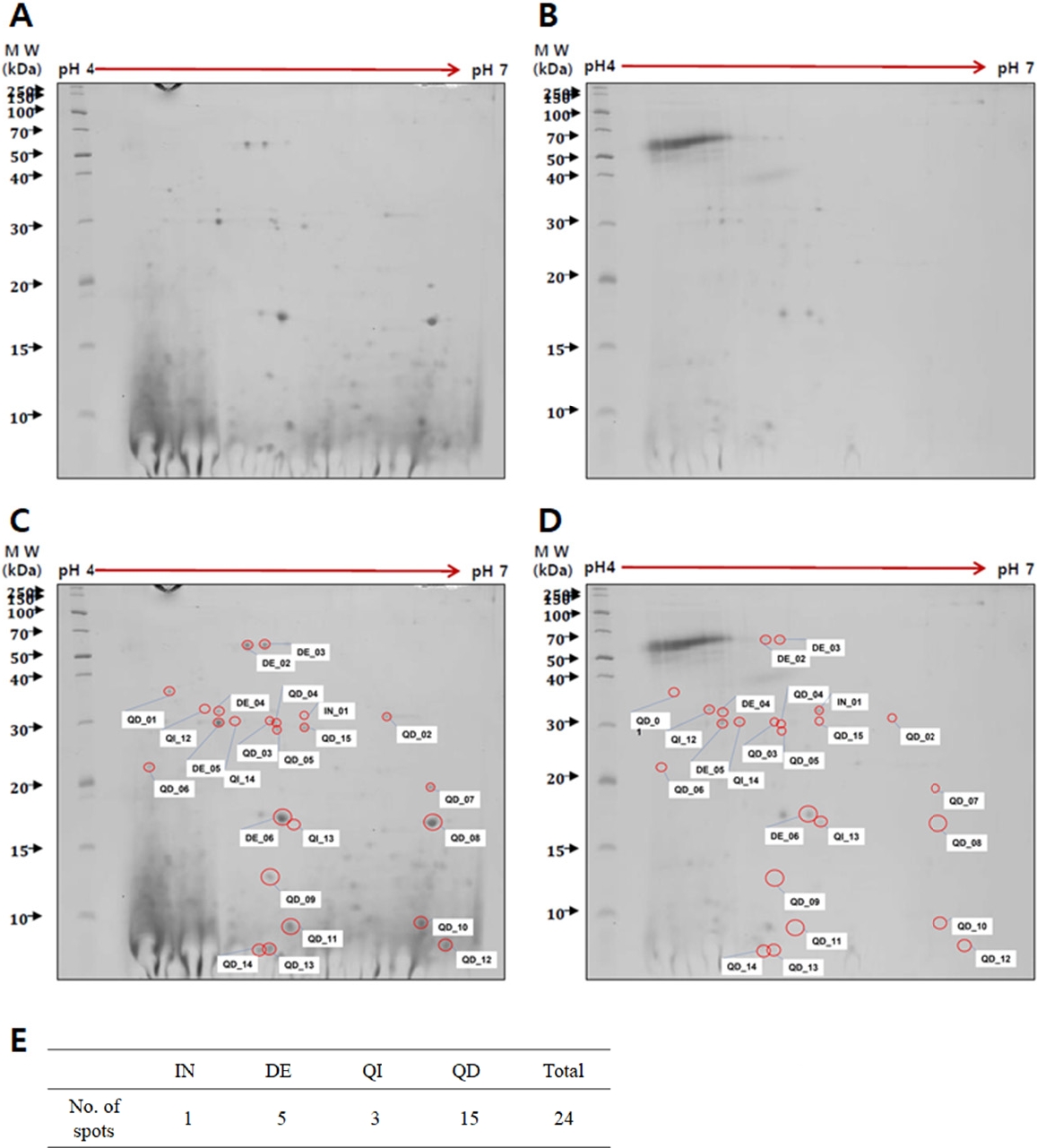

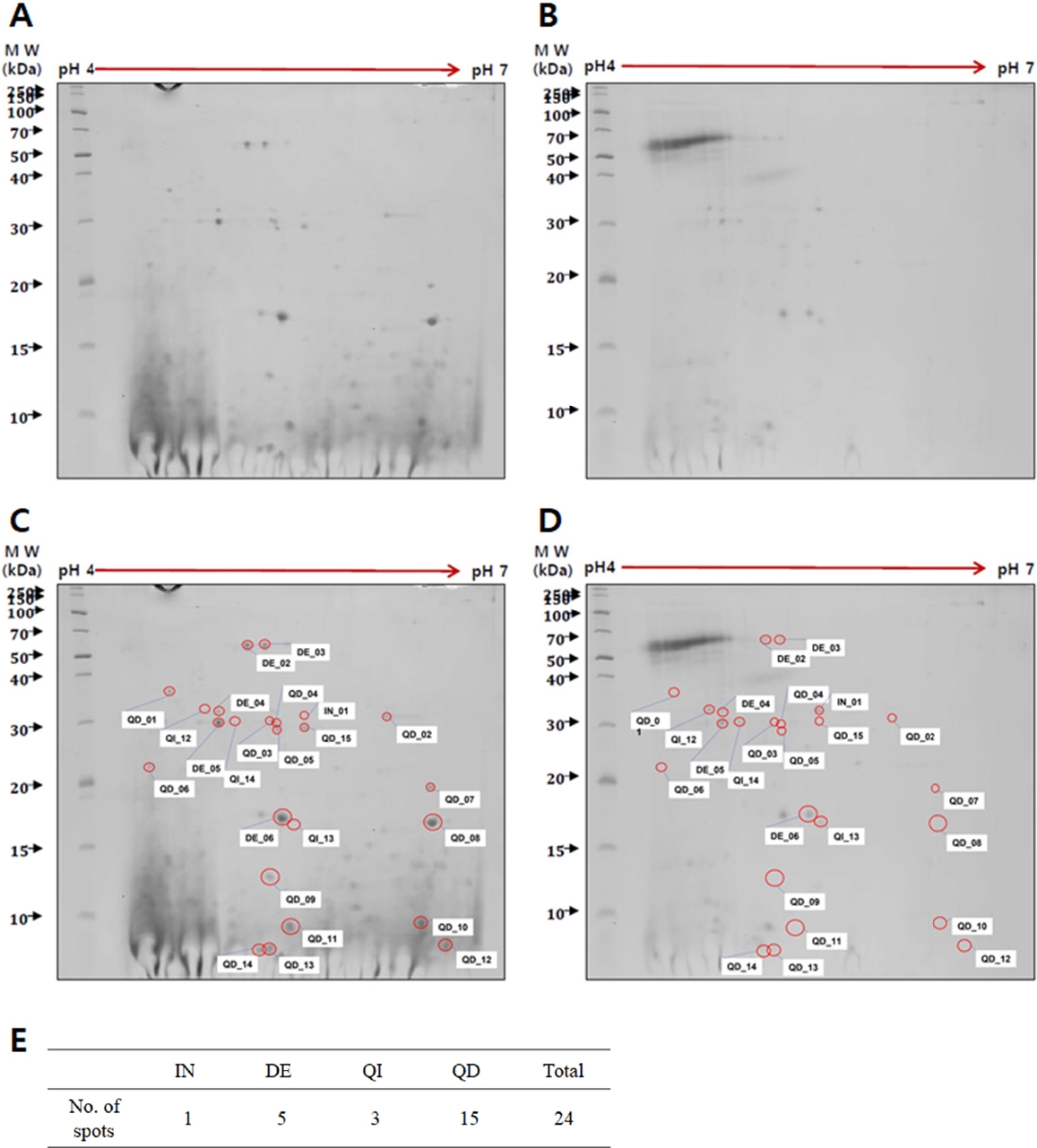

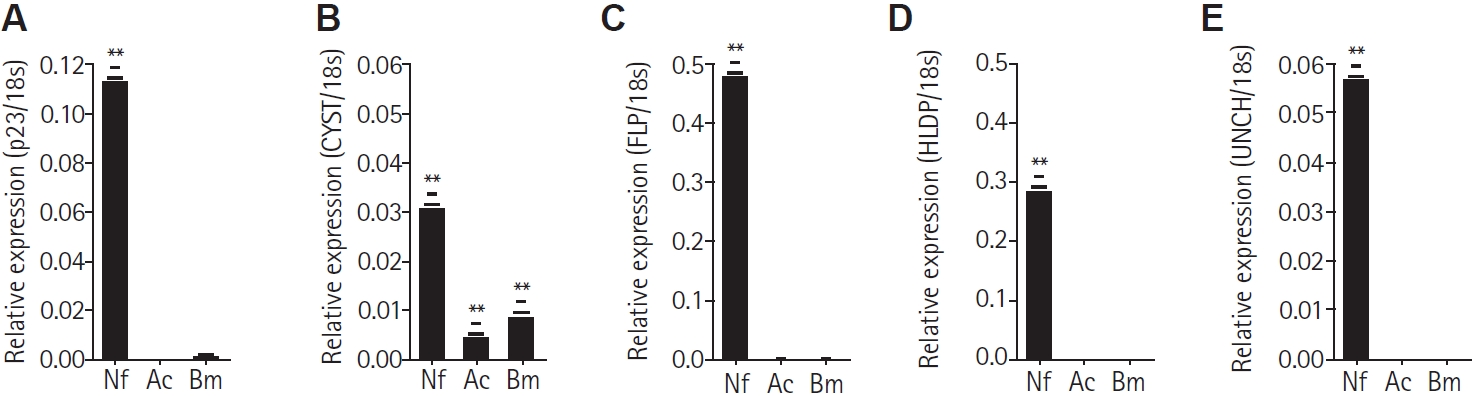

Comparison of proteins between trophozoite lysates and conditioned media of N. fowleri

To identify

Naegleria-preferentially secreted proteins, a comparison was made between trophozoite cell lysates (

Fig. 1A) and conditioned media (

Fig. 1B) of

N. fowleri using 2-DE analysis. Protein spots were found to be weakly acidic, concentrating along the center of the pH 3–10 gradient strip (data not shown). Optimal protein spot distribution and resolution were achieved using a pH 4–7 strip and 10% SDS-PAGE (

Fig. 1). The 2-DE analysis identified 24 proteins with differential expression in the conditioned media relative to the trophozoite lysates. The analysis revealed 1 increased protein (IN01), 5 decreased proteins (DE02 to DE06), 3 qualitative increased proteins (QI12 to QI14), and 15 qualitative decreased proteins (QD01 to QD15). Each protein spot was labeled with a number (

Fig. 1C,

D), and the number of spots classified by expression patterns was organized into a table (

Fig. 1E).

LC-MS/MS analysis of proteins isolated from 2-DE gels identified various proteins derived from

Naegleria spp. To search for sequence similarity matches specific to a taxonomy group or species, the UniProt (

https://www.uniprot.org) and NCBI BLAST (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) databases were utilized. Of the 24 proteins that exhibited differential expression in the 2-DE analysis, 18 were confirmed to be proteins of

N. fowleri (

Table 2). According to NCBI BLAST results, among these 18

N. fowleri proteins, 15 were identified as hypothetical proteins, and 3 showed high similarity to fowlerpain-2. The protein analysis results for all spots are shown in

Table 2.

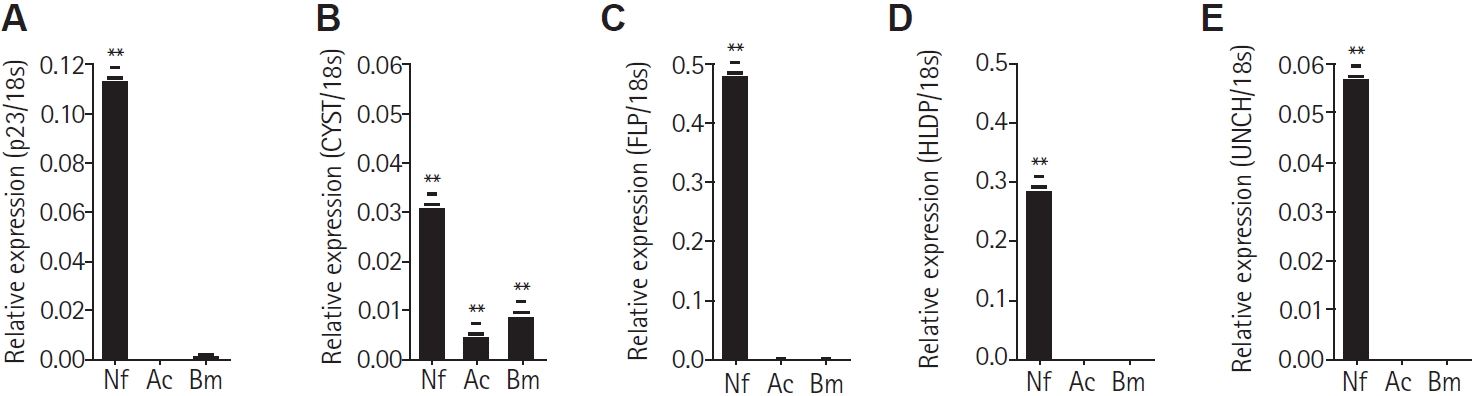

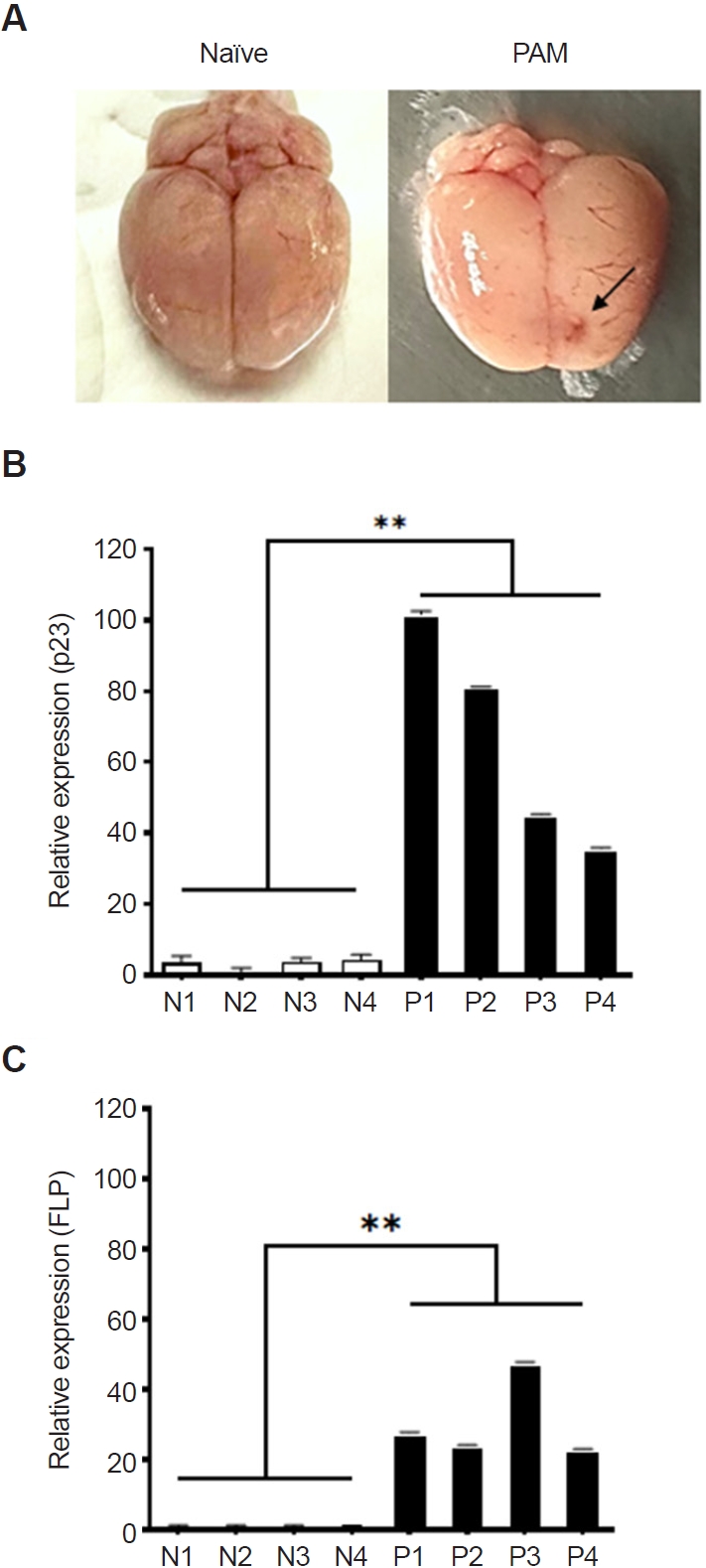

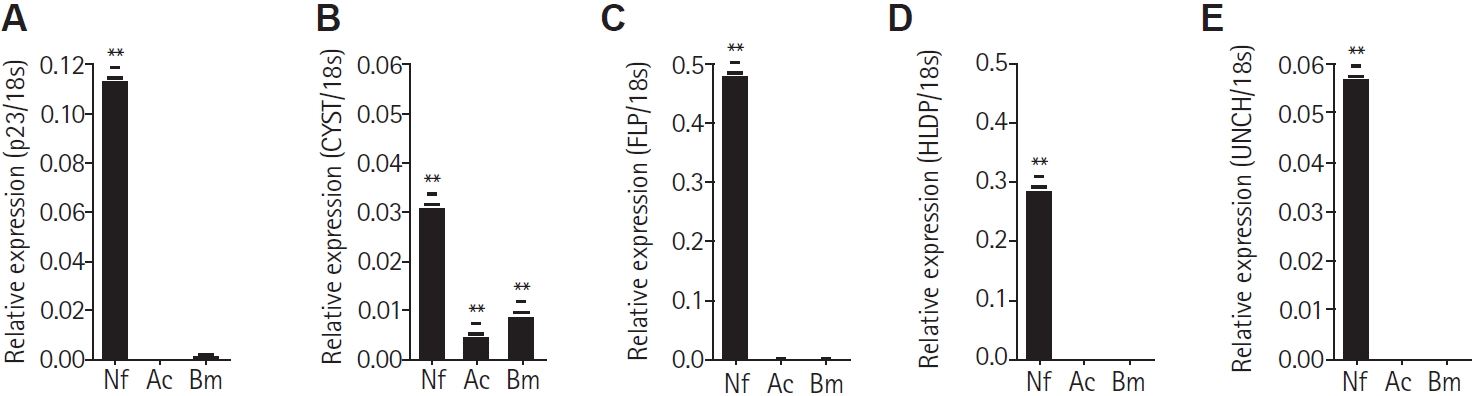

From the

Naegleria-preferential proteins identified in the 2-DE analysis, 5 proteins were selected based on their putative functions according to UniProt search results. These proteins were chosen to verify their preferential expression in

N. fowleri among free-living amoebae. Primers targeting each gene were designed for the following proteins: p23-like domain–containing protein (p23), cystatin-like domain–containing protein (CYST), fowlerpain-2 (FLP), hemerythrin family non-heme iron protein (HLDP), and uncharacterized protein (UNCH). These along with the 18S reference gene, are listed in

Table 1. The cDNA synthesized from total the RNA of

N. fowleri,

A. castellanii, and

B. mandrillaris was subjected to real-time PCR. All 5 genes were found to be significantly expressed in

N. fowleri and not in

A. castellanii and

B. mandrillaris (

Fig. 2A-

E). However, the CYST gene was observed to be slightly expressed in

Acanthamoeba and

Balamuthia (

Fig. 2B).

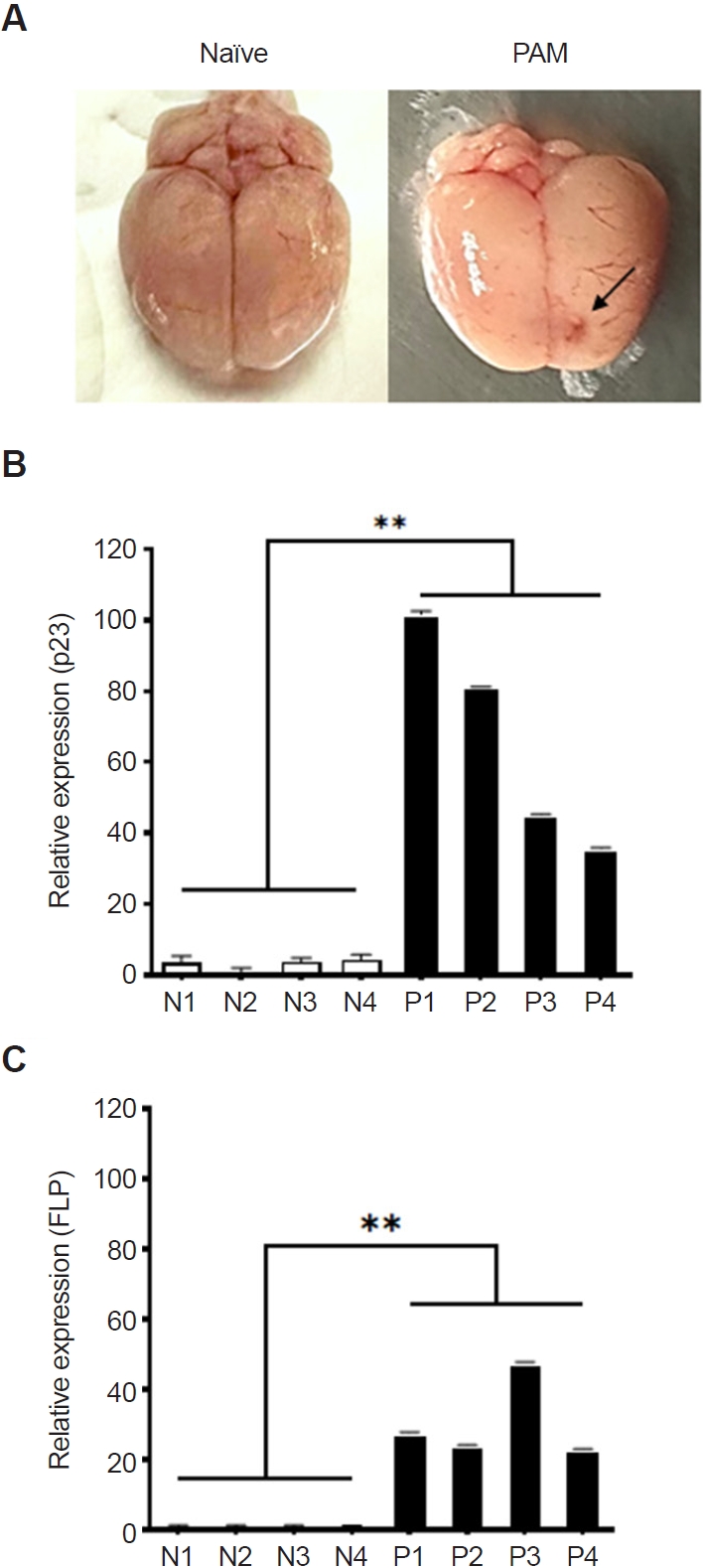

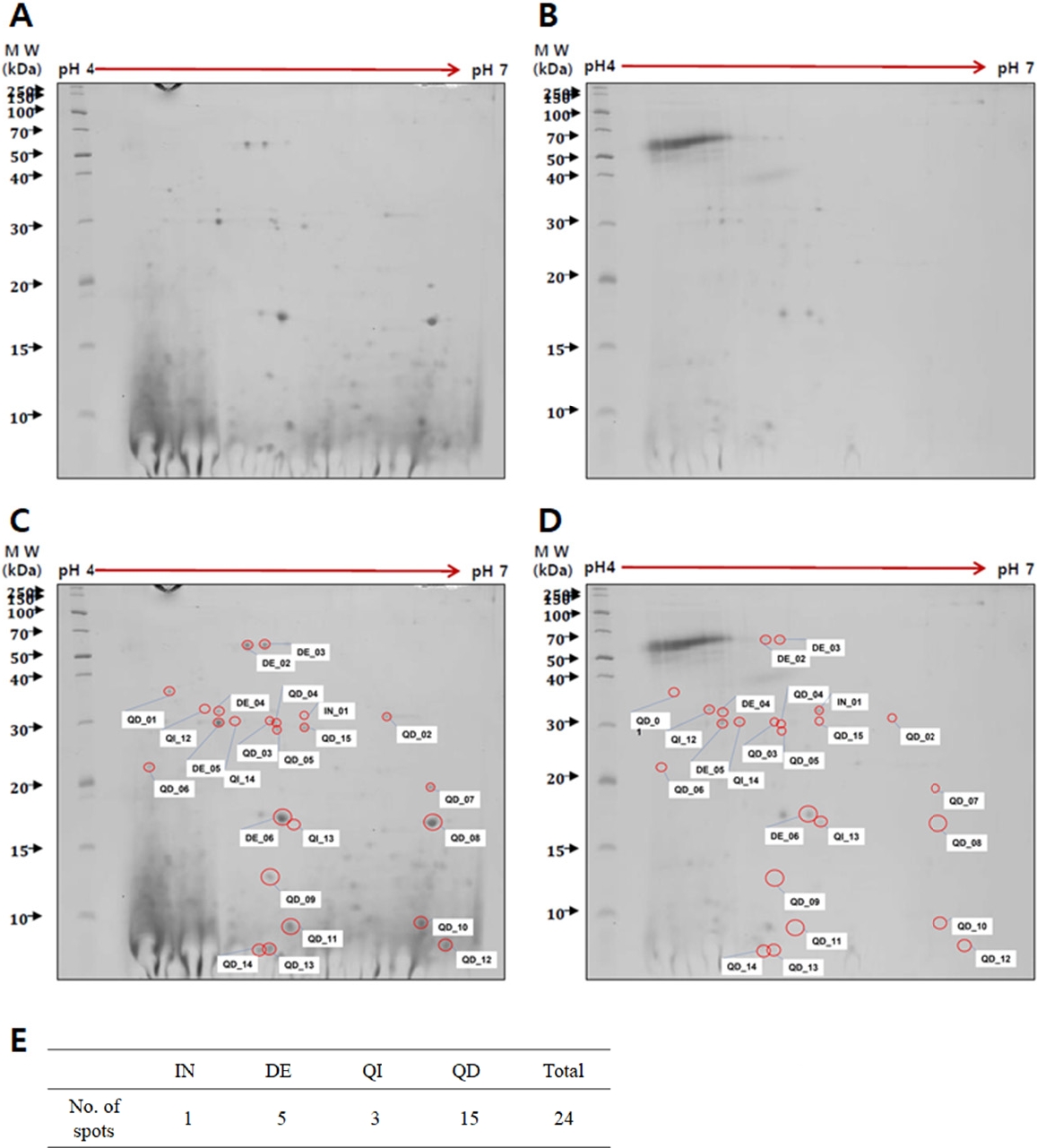

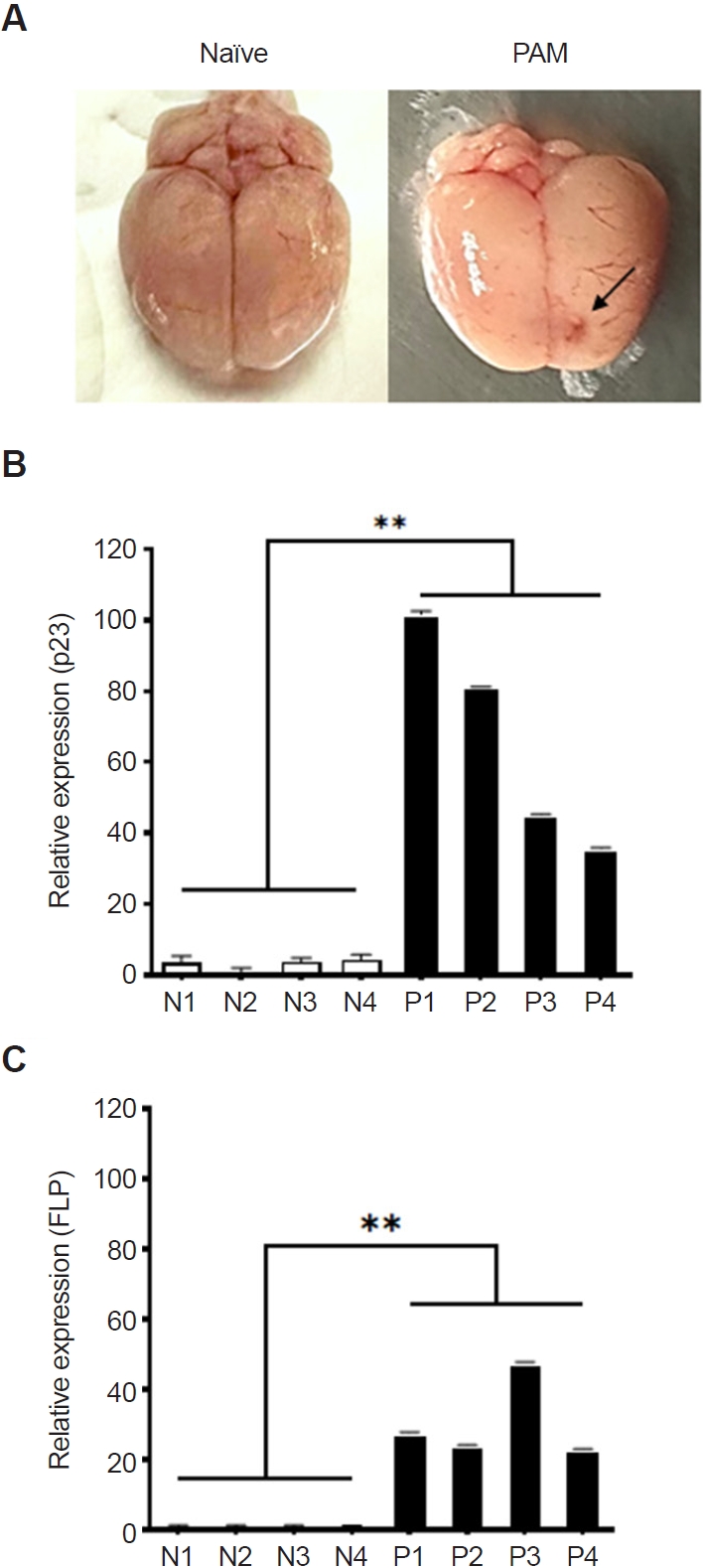

To evaluate the potential of

N. fowleri-preferentially secreted proteins as diagnostic candidates, PAM animal models were developed by infecting them with

N. fowleri, and real-time PCR was performed using brain tissue (

Fig. 3). All 4 mice with induced PAM succumbed to the infection between days 8 and 12, showing similar patterns of inflammation in the frontal brain regions (

Fig. 3A, indicated by an arrow). RNA was extracted from the brain tissue of the PAM models, followed by cDNA synthesis. Real-time PCR was performed for the 5 mentioned protein genes, revealing significant overexpression of the p23-like domain-containing protein (p23) and fowlerpain-2 (FLP) in the PAM models. The p23-like domain-containing protein gene was overexpressed in PAM mice by 101.9, 81.2, 45.2, and 35.7 times compared to the control group (

Fig. 3B). Similarly, the fowlerpain-2 protein gene was overexpressed by 27.7, 24.2, 47.8, and 23.0 times (

Fig. 3C). The cystatin-like domain–containing protein, hemerythrin family non-heme iron protein, and uncharacterized protein genes were either not significantly expressed or showed large error margins in the brain tissue of the PAM model (data not shown).

Discussion

Based on the comparative analysis of proteins though 2-DE analysis between trophozoite lysates and conditioned media of N. fowleri, 24 proteins with altered expression in conditioned media were identified. Further utilization of LC-MS/MS enabled the identification of 18 N. fowleri-preferential proteins. Gene expression analysis through real-time PCR provided additional evidence of the specificity of 5 proteins to N. fowleri.

Due to the lack of extensive database information on

N. fowleri, the results of the LC-MS/MS analysis were searched for similarity using the UniProt and NCBI BLAST websites (

Table 2). UniProt and NCBI BLAST are valuable bioinformatics resources with different, albeit related, purposes. NCBI BLAST is primarily used for sequence similarity searching, comparing a query sequence against a database to find homologous sequences and infer functional relationships. In contrast, UniProt is a comprehensive protein knowledgebase that integrates sequence, structure, function, and other relevant data. While UniProt also offers a BLAST tool for sequence similarity searches, its core function is to provide a curated and annotated resource for protein information. According to the NCBI BLAST results, most of the proteins identified by 2-DE analysis were classified as hypothetical proteins. However, in this study, 5 proteins were selected for further analysis based on their putative functions from the UniProt search results.

Spot QD06 was identified as a p23-like domain-containing protein, known to act as a co-chaperone of Hsp90 and facilitate the folding of various regulatory proteins [

22]. However, since multiple Hsp90-encoding genes have been reported in the

N. fowleri genome and none appear to be species-preferential, this protein was excluded from antibody development [

23]. Spot QD09 corresponded to a protein containing a cystatin-like domain, classified within the cystatin family of cysteine protease inhibitors. These proteins typically consist of a single domain and are upregulated in brain tissue environments, where they suppress the activity of host cathepsins K and L, thereby enhancing parasite survival and pathogenicity [

24]. Spots DE05, QI14, and QD15 were identified as fowlerpain-2, a cysteine protease secreted by

N. fowleri that contributes to host tissue destruction, traversal of the blood–brain barrier, and invasion of the central nervous system [

25]. Spot QD10 was a member of the hemerythrin family, which binds and consumes nitric oxide produced by macrophages, thus neutralizing nitric oxide–mediated amoebicidal mechanisms and promoting immune evasion [

24]. Spot QD08 was an uncharacterized protein, and due to the lack of functional information, it was excluded from further investigation. To evaluate whether these genes were preferentially expressed in

N. fowleri, real-time PCR analysis was conducted using

A. castellanii and

B. mandrillaris, 2 other free-living amoebae associated with encephalitis. All 5 genes were expressed at the highest levels in

N. fowleri, while their expression in

A. castellanii and

B. mandrillaris was significantly lower or not expressed (

Fig. 2). Among these, the genes for the p23-like domain-containing protein (QD06) and fowlerpain-2 (DE05, QI14, and QD15) were significantly overexpressed in the brain tissue of the PAM mouse model (

Fig. 3). Based on these results, the proteins corresponding to spots DE05, QI14, and QD15 were selected as

N. fowleri-preferentially secreted proteins, and further research is underway.

In previous studies exploring the secreted pathogenic proteins of

A. castellanii, a wide variety of secreted proteins were identified through 2-DE analysis [

20]. However, in this study, the number of secreted proteins identified in

N. fowleri was much smaller than expected. This was likely due to our use of serum-free conditioned media, which was employed to minimize strong background signals caused by residual fetal bovine serum proteins. However, the serum-free conditions may have compromised the physiological activity of

N. fowleri, leading to reduced protein secretion and a consequent decrease in the number of detectable spots. As a result, the range of candidate proteins available for screening of

N. fowleri–preferentially secreted proteins was limited. Further studies should focus on optimizing culture conditions to enhance secreted protein yield and validate the diagnostic utility of the selected proteins in clinical and experimental models. Meanwhile, some protein genes showed non-significant or highly variable real-time PCR results in the brain tissue of the PAM animal model (data not shown). This variability may be influenced by differences in the severity of PAM symptoms and the specific brain regions sampled. To address this, further validation of PCR results in a larger number of PAM animal models is warranted.

In summary, the comprehensive proteomic and gene expression analyses of N. fowleri provide a foundational understanding of its secretome and highlight potential targets for the development of antibody-based and molecular biological diagnostic methods. Further studies should focus on the functional characterization of identified proteins to enhance our understanding of N. fowleri biology and to develop strategies to combat infections caused by free-living amoebae including N. fowleri.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Moon EK. Data curation: Lee HA, Quan FS, Kong HH, Moon EK. Funding acquisition: Moon EK. Investigation: Jo HJ, Lee HA, Moon EK. Methodology: Jo HJ, Lee HA, Quan FS, Kong HH, Moon EK. Validation: Moon EK. Writing – original draft: Jo HJ. Writing – review & editing: Lee HA, Quan FS, Kong HH, Moon EK.

-

Conflict of interest

Fu-Shi Quan serves as an editor of Parasites, Hosts and Diseases but had no involvement in the decision to publish this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study were reported.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00346635).

Fig. 1.Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of proteins in Naegleria fowleri lysates and conditioned media. A comparison of proteins between trophozoite lysates (A) and conditioned media (B) revealed 24 proteins with differential expression. Each protein spot was labeled with a number indicating whether the protein was increased (IN), decreased (DE), qualitative increased (QI), or qualitative decreased (QD) in the conditioned media compared to the trophozoite lysates (C, D). The number of spots classified by expression patterns was organized into a table (E). MW: molecular weight.

Fig. 2.Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. Real-time PCR was performed on cDNA synthesized from the total RNA of Naegleria fowleri (Nf), Acanthamoeba castellanii (Ac), and Balamuthia mandrillaris (Bm). The relative expression levels were normalized to the 18S rDNA of each sample and calculated using the formula 2^−ΔCt (where ΔCt = Ct_target − Ct_18S). Bars represent the mean±SD (n=3). The p23-like domain–containing protein (p23), cystatin-like domain–containing protein (CYST), fowlerpain-2 (FLP), hemerythrin family non-heme iron protein (HLDP), and uncharacterized protein (UNCH) each exhibited their highest expression in N. fowleri (A-E). Data are expressed as mean±SD, and asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the target gene and 18S rDNA (**P<0.01).

Fig. 3.Detection of Naegleria fowleri–preferential proteins in primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) animal models. PAM animal models were developed by infecting them with N. fowleri (A, indicated by an arrow), and real-time PCR was performed using cDNA synthesized from the total RNA of brain tissue (B, C). The p23-like domain-containing protein and the fowlerpain-2 gene were significantly overexpressed in PAM brain tissue compared to the control group. Naïve refers to the brain of the negative control group (N), and PAM refers to the brain of the N. fowleri–infected group (P). Data are expressed as mean±SD, and asterisks denote statistical significance between the means of the 2 groups (**P<0.01).

Table 1.Primer sequences for real-time PCR

Table 1.

|

No. |

Group ID |

Product |

Primer sequences (5’→3’) |

|

1 |

QD06 |

Hypothetical protein (p23_like domain) |

F: GTGGACTGGTCGAAATGGGT |

|

R: CCTCCTCTTCTTCATCACCCG |

|

2 |

QD09 |

Hypothetical protein (cystatin-like domain) |

F: GAACAAAAGCTCGGCAAGACA |

|

R: CTCACCTGTCTTGACGCCAT |

|

3 |

DE05, QI14, QD15 |

Fowlerpain-2 (cysteine protease) |

F: AGTGGATCATTGGCTGGTGG |

|

R: TCCAAACCCCAGTCAACTCC |

|

4 |

QD10 |

Hypothetical protein (hemerythrin family non-heme iron protein) |

F: CTGGGACTCTTCTTTCTGCGT |

|

R: TGCGAACAAGTCCTCCTCAG |

|

5 |

QD08 |

Uncharacterized protein |

F: GTTCCTTCACTGGAGGCTCA |

|

R: ACTGGTGAGAAGAAGAAGAATTTGC |

|

6 |

Control_Nf |

Naegleria fowleri 18S rDNA |

F: GGAGAGGGAGCCTGAGAGAT |

|

R: CTGGCACCAGACTTTTCCTC |

|

7 |

Control_Ac |

Acanthamoeba castellanii 18S rDNA |

F: CGTGCTGGGGATAGATCATT |

|

R: AAAGGGGAGACCTCACAACC |

|

8 |

Control_Bm |

Balamuthia mandrillaris 18S rDNA |

F: TGACTCAACACGGGGAAACT |

|

R: TCACCCCCTGGTTTTGAATA |

Table 2.Secreted proteins from Naegleria fowleri trophozoites

Table 2.

|

No. |

Group ID |

Uniprot |

NCBI |

Score |

Mass (Da) |

|

Name |

Accession No. |

Name |

Accession No. |

|

1 |

IN01 |

Profilin |

tr|A0A6A5BHQ3|A0A6A5BHQ3_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_006373 [Naegleria fowleri] |

KAF0974341.1 |

126 |

14,000 |

|

2 |

DE02 |

Triosephosphate isomerase |

tr|A0A6A5BWU3|A0A6A5BWU3_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_012394 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0981737.1 |

324 |

27,879 |

|

3 |

DE03 |

Triosephosphate isomerase |

tr|A0A6A5BWU3|A0A6A5BWU3_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_012394 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0981737.1 |

137 |

27,879 |

|

4 |

DE04 |

Uncharacterized protein |

tr|A0AA88KE97|A0AA88KE97_NAELO |

Hypothetical protein C9374_009233 [N. lovaniensis] |

KAG2377322.1 |

27 |

108,339 |

|

5 |

DE05 |

Fowlerpain-2 |

tr|A0A1L1XWF9|A0A1L1XWF9_NAEFO |

Fowlerpain-2 [N. fowleri] |

AKC55968.1 |

751 |

34,550 |

|

6 |

DE06 |

Uncharacterized protein |

tr|A0AAW2Z485|A0AAW2Z485_9EUKA |

Hypothetical protein AKO1_013992 [N. fowleri] |

KAL0483734.1 |

23 |

42,132 |

|

7 |

QI12 |

Histidine kinase |

tr|D2VZJ1|D2VZJ1_NAEGR |

Predicted protein [N. gruberi] |

EFC37856.1 |

18 |

61,785 |

|

8 |

QI13 |

NUC153 domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5CCI8|A0A6A5CCI8_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_007451 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0984274.1 |

21 |

93,035 |

|

9 |

QI14 |

Fowlerpain-2 |

tr|A0A1L1XWF9|A0A1L1XWF9_NAEFO |

Fowlerpain-2 [Naegleria fowleri] |

AKC55968.1 |

794 |

34,550 |

|

10 |

QD01 |

ABC transporter protein ARB1 |

tr|A0AAW2YMA9|A0AAW2YMA9_9EUKA |

ABC transporter protein ARB1 [Acrasis kona] |

KAL0478427.1 |

21 |

66,226 |

|

11 |

QD02 |

Carboxypeptidase |

tr|A0A6A5CIS9|A0A6A5CIS9_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_000254 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0985215.1 |

67 |

56,379 |

|

12 |

QD03 |

Dopey N-terminal domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5C095|A0A6A5C095_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_001661 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0979318.1 |

96 |

214,996 |

|

13 |

QD04 |

Dopey N-terminal domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5C095|A0A6A5C095_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_001661 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0979318.1 |

116 |

214,996 |

|

14 |

QD05 |

Dopey N-terminal domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5C095|A0A6A5C095_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_001661 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0979318.1 |

35 |

214,996 |

|

15 |

QD06 |

CS domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5BBV5|A0A6A5BBV5_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_006609 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0974577.1 |

189 |

20,010 |

|

16 |

QD07 |

Uncharacterized protein |

tr|A0A6A5BFT0|A0A6A5BFT0_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_003988 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0976693.1 |

60 |

18,525 |

|

17 |

QD08 |

Uncharacterized protein |

tr|A0A6A5BFT0|A0A6A5BFT0_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_003988 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0976693.1 |

130 |

18,525 |

|

18 |

QD09 |

Cystatin domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5BX69|A0A6A5BX69_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_002161 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0979091.1 |

157 |

10,408 |

|

19 |

QD10 |

Hemerythrin-like domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5BCB0|A0A6A5BCB0_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_010118 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0971589.1 |

1,750 |

13,452 |

|

20 |

QD11 |

Uncharacterized protein |

tr|A0AAW2Z485|A0AAW2Z485_9EUKA |

Hypothetical protein AKO1_013992 [A. kona] |

KAL0483734.1 |

36 |

42,132 |

|

21 |

QD12 |

Glutamyl-tRNA reductase |

tr|A0AAW2YMP3|A0AAW2YMP3_9EUKA |

Glutamyl-tRNA reductase [A. kona] |

KAL0478153.1 |

16 |

31,447 |

|

22 |

QD13 |

Predicted protein |

tr|D2VNK6|D2VNK6_NAEGR |

Predicted protein [N. gruberi] |

EFC41752.1 |

29 |

59,920 |

|

23 |

QD14 |

Dopey N-terminal domain-containing protein |

tr|A0A6A5C095|A0A6A5C095_NAEFO |

Hypothetical protein FDP41_001661 [N. fowleri] |

KAF0979318.1 |

25 |

214,996 |

|

24 |

QD15 |

Fowlerpain-2 |

tr|A0A1L1XWF9|A0A1L1XWF9_NAEFO |

Fowlerpain-2 [N. fowleri] |

AKC55968.1 |

250 |

34,550 |

References

- 1. Alanazi A, Younas S, Ejaz H, et al. Advancing the understanding of Naegleria fowleri: global epidemiology, phylogenetic analysis, and strategies to combat a deadly pathogen. J Infect Public Health 2025;18:102690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2025.102690

- 2. Ben Youssef M, Omrani A, Sifaoui I, et al. Amoebicidal thymol analogues against brain-eating amoeba, Naegleria fowleri. Bioorg Chem 2025;159:108346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2025.108346

- 3. Stahl LM, Olson JB. Environmental abiotic and biotic factors affecting the distribution and abundance of Naegleria fowleri. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2020;97:fiaa238. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa238

- 4. Mungroo MR, Khan NA, Siddiqui R. Naegleria fowleri: diagnosis, treatment options and pathogenesis. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2019;7:67-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678707.2019.1571904

- 5. Miko S, Cope JR, Hlavsa MC, et al. A case of primary amebic meningoencephalitis associated with surfing at an artificial surf venue: environmental investigation. ACS ES T Water 2023;3:1126-33. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.2c00592

- 6. Jarolim KL, McCosh JK, Howard MJ, John DT. A light microscopy study of the migration of Naegleria fowleri from the nasal submucosa to the central nervous system during the early stage of primary amebic meningoencephalitis in mice. J Parasitol 2000;86:50-5. https://doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0050:ALMSOT]2.0.CO;2

- 7. Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2007;50:1-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00232.x

- 8. Heilmann A, Rueda Z, Alexander D, Laupland KB, Keynan Y. Impact of climate change on amoeba and the bacteria they host. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can 2024;9:1-5. https://doi.org/10.3138/jammi-2023-09-08

- 9. Zahid MF, Saad Shaukat MH, Ahmed B, et al. Comparison of the clinical presentations of Naegleria fowleri primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with pneumococcal meningitis: a case-control study. Infection 2016;44:505-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-016-0878-y

- 10. Maciver SK, Piñero JE, Lorenzo-Morales J. Is Naegleria fowleri an emerging parasite? Trends Parasitol 2020;36:19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.10.008

- 11. Chen S, Che C, Lin W, et al. Recognition of devastating primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) caused by Naegleria fowleri: another case in south China detected via metagenomics next-generation sequencing combined with microscopy and a review. Front Trop Dis 2022;3:899700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2022.899700

- 12. Maďarová L, Trnková K, Feiková S, Klement C, Obernauerová M. A real-time PCR diagnostic method for detection of Naegleria fowleri. Exp Parasitol 2010;126:37-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2009.11.001

- 13. Aykur M, Dirim Erdogan D, Selvi Gunel N, et al. Genotyping and molecular identification of Acanthamoeba genotype T4 and Naegleria fowleri from cerebrospinal fluid samples of patients in Turkey: is it the pathogens of unknown causes of death? Acta Parasitol 2022;67:1372-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11686-022-00597-3

- 14. McKenna JP, Fairley DJ, Shields MD, et al. Development and clinical validation of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for the rapid detection of Neisseria meningitidis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;69:137-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.008

- 15. Mahittikorn A, Mori H, Popruk S, et al. Development of a rapid, simple method for detecting Naegleria fowleri visually in water samples by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). PLoS One 2015;10:e0120997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120997

- 16. Jamerson M, Schmoyer JA, Park J, Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral GA. Identification of Naegleria fowleri proteins linked to primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Microbiology (Reading) 2017;163:322-32. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.000428

- 17. Kim JH, Yang AH, Sohn HJ, et al. Immunodominant antigens in Naegleria fowleri excretory: secretory proteins were potential pathogenic factors. Parasitol Res 2009;105:1675-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-009-1610-y

- 18. Flores-Huerta N, Sánchez-Monroy V, Rodríguez MA, Serrano-Luna J, Shibayama M. A comparative study of the membrane proteins from Naegleria species: a 23-kDa protein participates in the virulence of Naegleria fowleri. Eur J Protistol 2020;72:125640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejop.2019.125640

- 19. Lê HG, Kang JM, Võ TC, Yoo WG, Na BK. Naegleria fowleri extracellular vesicles induce proinflammatory immune responses in BV-2 microglial cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:13623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241713623

- 20. Moon EK, Choi HS, Park SM, Kong HH, Quan FS. Comparison of proteins secreted into extracellular space of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Acanthamoeba castellanii. Korean J Parasitol 2018;56:553-8. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2018.56.6.553

- 21. Kim MJ, Moon EK, Jo HJ, Quan FS, Kong HH. Identifying the function of genes involved in excreted vesicle formation in Acanthamoeba castellanii containing Legionella pneumophila. Parasit Vectors 2023;16:215. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05824-y

- 22. Weaver AJ, Sullivan WP, Felts SJ, Owen BAL, Toft DO. Crystal structure and activity of human p23, a heat shock protein 90 co-chaperone. J Biol Chem 2000;275:23045-52. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M003410200

- 23. Joseph SJ, Park S, Kelley A, et al. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analysis of Naegleria fowleri clinical and environmental isolates. mSphere 2021;6:e0063721. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00637-21

- 24. Malych R, Folgosa F, Pilátová J, et al. Eating the brain: a multidisciplinary study provides new insights into the mechanisms underlying the cytopathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri. PLoS Pathog 2025;21:e1012995. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1012995

- 25. Aldape K, Huizinga H, Bouvier J, McKerrow J. Naegleria fowleri: characterization of a secreted histolytic cysteine protease. Exp Parasitol 1994;78:230-41. https://doi.org/10.1006/expr.1994.1023