Abstract

Even though Taenia spp. eggs are occasionally discovered from archeological remains around the world, these eggs have never been discovered in ancient samples from Korea. When we attempted to re-examine the archeological samples maintained in our collection, the eggs of Taenia spp., 5 in total number, were recovered from a tomb of Gongju-si. The eggs had radially striated embryophore, and 37.5-40.0 µm×37.5 µm in size. This is the first report on taeniid eggs from ancient samples of Korea, and it is suggested that intensive examination of voluminous archeological samples should be needed for identification of Taenia spp.

-

Key words: Taenia sp., egg, archeological, Gongju-si

The rapid development of paleoparasitology in Korea has occurred in recent years, especially with discovery of mummies from the Joseon Dynasty [

1,

2]. When the soil sediments from Korean medieval tombs were examined for the presence of parasite eggs, we also recovered numerous eggs [

3]. The ancient eggs were mostly recovered from the samples of tombs encapsulated with lime-soil mixture barrier (LSMB), which were commonly constructed for ruling class from the 15th to 19th centuries [

4]. The recovered eggs mainly belonged to

Trichuris trichiura and

Ascaris lumbricoides, while

Clonorchis sinensis,

Paragonimus westermani, and

Metagonimus yokogawai were occasionally found [

3]. Even the larvae of

Strongyloides stercoralis and the eggs of

Gymnophalloides seoi were discovered in our studies [

2,

5].

Human taeniasis is known to be distributed worldwide, and the beef tapeworm,

Taenia saginata, has been regarded as dominant over

Taenia solium [

6]. However, we could not discover any

Taenia spp. eggs in archeological samples from Korea. Based on paleoparasitological reports from the world, the first discovery of ancient

Taenia spp. eggs was from a 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy [

7]. Subsequently, taeniid eggs were reported from various archeological sites around the world. Briefly, the eggs were discovered in a mummy from a Christian Necropolis in Egypt, the embalming reject jars of Egypt, and a Han-Dynasty mummy in China [

8-

10]. Even the characteristic feature of cysticercosis was also reported in an Egyptian mummy from the Ptolemaic period [

11]. Based on these findings, it was very unusual that taeniid eggs have not been found from archeological remains in Korea despite that Korea is known to be an endemic area for taeniasis. Even though the locality and date was not described, the prevalence of

Taenia tapeworms among Koreans was quoted as 16% or 7-8% in the 1920s according to a report by Inoba in 1924, as reviewed by Eom and Rim [

12]. In addition, nationwide parasitological surveys showed that the egg-positive rates for taeniasis fluctuated between 0.02% and 1.9%, even in the late 20th century [

12,

13].

While molecular paleoparasitological diagnosis by using PCR is sensitive enough to diagnose the parasite in a sample with only 30 parasite eggs, microscopic analysis often fails to detect small numbers of parasite eggs [

14]. Hence, voluminous examination of archeological samples is needed for detection of low-density eggs when molecular diagnosis is unavailable. To confirm the negativity of

Taenia spp. eggs in our archeologically-obtained collection, we re-examined the samples maintained in our collection, especially those in perfect preservation status. The sample collected from the tomb in Gongju-si was one such example, worthy of re-examination. In the tomb of Gongju-si, 2 coffins were found encapsulated with lime-soil mixture barrier (LSMB), possibly those of a husband and a wife (

Fig. 1). As the husband was buried on the right side to his wife during the Joseon Dynasty, the left coffin was supposed to be that of the husband. The sample for the present study was collected from the husband's coffin, that consisted of the soil sediment spread upon the hip bones of a man living in the late 17th century. In our previous examinations, eggs of

Ascaris lumbricoides,

Trichuris trichiura, and

Paragonimus westermani along with the larvae of

Strongyloides stercoralis were detected from the left coffin [

5]. This abundance of helminth ova or larvae in this sample raised hope that we might discover

Taenia sp. eggs from this sample too, considering prevalence of

Taenia parasitism among the Korean population. The rehydration method used in this study generally followed the method previously reported [

5]. While a 400-µl of rehydrated sample was examined before, 18 ml of rehydrated sample was examined in the present study, which was nearly 45 times more than the previous examinations.

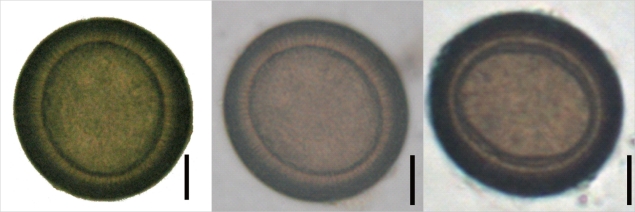

In the present study, the eggs found at first examination, i.e.,

A. lumbricoides,

T. trichiura, and

P. westermani, were also recovered (data not shown). In addition, taeniid eggs were recovered from the samples. They revealed characteristic features of taeniid eggs with a radially striated embryophore, although hooklets were not clearly observed (

Fig. 2). A total of 5

Taenia spp. eggs were recovered from the sample. Since 2 of them were unmeasurable due to a partial destruction, 3 of them were photographed and measured (

Fig. 2). They were 37.5-40.0 µm×37.5 µm in size, and 5.6 µm in thickness of the embryophore.

This is the first discovery of taeniid eggs from archeological samples of Korea. Since species differentiation was not possible by microscopic examinations, the precise species should be evaluated further in forthcoming studies, especially by molecular studies. Considering that taeniid eggs were not found in the first examination and that only 5 Taenia eggs were discovered from all of the remaining samples at this time, intensive examination on voluminous samples will be needed for identification of Taenia eggs in archeological samples from Korea.

Among the various helminth eggs, those of

Taenia spp. have not frequently been discovered in archeological samples [

10]. The scarcity of taeniid eggs could be explained as follows: First, the ancient taeniid eggs were usually preserved in mummies, but not in soil sediments at archeological sites [

10]. In addition, among various geological strata in archeological sites of Belgium, the eggs of

Taenia spp. were discovered only in those of recent days [

15]. This suggested that the egg shells of

Taenia spp. are fragile and not suitable for long-term preservations [

9]. Second, the infection rate of

Taenia spp. might be lower than that of other helminth species. In Korea, the positive rate of

Taenia spp. was only 1.9% in 1971 when the overall parasite positive rate was 84.3% [

16]. Third,

Taenia spp. eggs escape from the uterus through the ruptured wall after the gravid proglottid becomes free from the strobila [

17]. This might result in scarcity of taeniid eggs in the coprolites or soil samples.

In order to find out more

Taenia spp. eggs in archeological samples from Korea, we should consider that

T. solium and

T. asiatica, especially the latter, were prevalent in Jeju-do with its complete life cycle. The report on Jeju inhabitants showed that 27.2% of them had an experience of eating raw pig liver, more than those of any other province [

12]. In fact, the taeniid infection rate of Jeju-do was 1.5% in 1992, while in other geographic areas the infection rate was ≤0.3% [

16]. Furthermore, 6% of the populations on Cheju Island (Jeju-do) were suspected to carry 2 adults of

T. asiatica on average in 1986 and 1987 [

18], and a survey of neurocysticercosis prevalence among epilepsy patients showed that the island had the highest positive rate (8.4%) among all areas of Korea [

19]. Therefore, our next paleoparasitological study must include works on samples from Jeju-do where the ancient taeniid eggs might have a greater likelihood of discovery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, 2010, Korea (NRICH-1017-B16F-1).

References

- 1. Seo M, Guk SM, Kim J, Chai JY, Bok GD, Park SS, Oh CS, Kim MJ, Yi S, Shin MH, Kang IU, Shin DH. Paleoparasitological report on the stool from a Medieval child mummy in Yangju, Korea. J Parasitol 2007;93:589-592.

- 2. Seo M, Shin DH, Guk SM, Oh CS, Lee EJ, Shin MH, Kim J, Lee SD, Kim YS, Yi YS, Spigelman M, Chai JY. Gymnophalloides seoi eggs from the stool of a 17th century female mummy found in Hadong, Republic of Korea. J Parasitol 2008;94:467-472.

- 3. Seo M, Oh CS, Chai JY, Lee SJ, Park JB, Lee BH, Park JH, Choi GH, Hong DW, Park HU, Shin DH. The influence of differential burial preservation on the recovery of parasite eggs in soil samples from Korean medieval tombs. J Parasitol 2010;96:366-370.

- 4. Koh BJ. Dasitaeeonan uriot. Hwangsaeng. 2006, Seoul, Korea. Dankook University Museum; pp 198-201.

- 5. Shin DH, Chai JY, Park EA, Lee W, Lee H, Lee JS, Choi YM, Koh BJ, Park JB, Oh CS, Bok GD, Kim WL, Lee E, Lee EJ, Seo M. Finding ancient parasite larvae in a sample from a male living in late 17th century. J Parasitol 2009;95:768-771.

- 6. Arambulo PV. On taeniasis and cysticercosis. Vet Gaz 1967;1:4-5.

- 7. Bouchet F, Harter S, Le Bailly M. The state of the art of paleoparasitological research in the old world. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003;98(suppl 1):95-101.

- 8. Le Bailly M, Mouze S, Rocha GC, Heim JL, Lichtenberg R, Dunand F, Bouchet F. Identification of Taenia sp. in a mummy from a christian necropolis in El-Deir, Oasis of Kharga, ancient Egypt. J Parasitol 2010;96:213-215.

- 9. Harter S, Le Bailly M, Janot F, Bouchet F. First paleoparasitological study of an embalming rejects jar found in Saqqara, Egypt. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003;98(suppl 1):119-121.

- 10. Goncalves MLC, Araujo A, Ferreira LF. Human intestinal parasites in the past: New findings and a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2003;98(suppl 1):103-118.

- 11. Bruschi F, Masetti M, Locci MT, Ciranni R, Fornaciari G. Short report: Cysticercosis in an Egyptian mummy of the late Ptolemaic period. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;74:598-599.

- 12. Eom KS, Rim HJ. Epidemiological understanding of Taenia tapeworm infections with special reference to Taenia asiatica in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2001;39:267-283.

- 13. Seo BS, Rim HJ, Loh IK, Lee SH, Cho SY, Park SC, Bae JW, Kim JH, Lee JS, Koo BY, Kim KS. Study on the status of helminthic infections in Koreans. Korean J Parasitol 1969;7:53-70.

- 14. Leles D, Araujo A, Ferreira LF, Vicente ACP, Iniquez AM. Molecular paleoparasitological diagnosis of Ascaris sp. from coprolites: New scenery of ascariasis in pre-Columian South America times. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008;103:106-108.

- 15. Rocha GC, Harter-Lailheugue S, Le Bailly M, Araujo A, Ferreria LF, da Serra-Freire NM, Bouchet F. Paleoparasitological remains revealed by seven historic contexts from "Place d'Armes", Namur, Belgium. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2006;101(suppl 2):43-52.

- 16. Korea Association of Health. Collected papers on parasite control in Korea. In commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Korea Association of Health. 1994.

- 17. Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 1984, 9th ed. Philadelphia, USA. Lea & Febiger; p 513.

- 18. Soh CT, Lee KT, Kim SH, Fan PC. Studies on epidemiology and chemotherapy of taeniasis on Cheju Island, Korea. Yonsei Rep Trop Med 1988;19:25-31.

- 19. Kong Y, Cho SY, Cho MS, Kwon OS, Kang WS. Seroepidemiological observation of Taenia solium cysticercosis in epileptic patients in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 1993;8:145-152.

Fig. 1Two coffins, possibly those of husband and wife, were found from a tomb encapsulated with lime soil mixture barrier (LSMB) in Gongju-si, Korea. As the husband was buried on the right side to his wife during the Joseon Dynasty, the left (arrow) was supposed to be that of the husband. The sample for the present study was collected from the left coffin, where the taeniid eggs were recovered.

Fig. 2Three eggs of Taenia sp. found in the tomb of Gongju-si, Korea. The radially striated embryophore is seen, 5.6 µm in thickness. ×400. Bar=10 µm.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Paleoparasitology research on ancient helminth eggs and larvae in the Republic of Korea

Jong-Yil Chai, Min Seo, Dong Hoon Shin

Parasites, Hosts and Diseases.2023; 61(4): 345. CrossRef - A comparison of ancient parasites as seen from archeological contexts and early medical texts in China

Hui-Yuan Yeh, Xiaoya Zhan, Wuyun Qi

International Journal of Paleopathology.2019; 25: 30. CrossRef - Discovery of Parasite Eggs in Archeological Residence during the 15th Century in Seoul, Korea

Pyo Yeon Cho, Jung-Min Park, Myeong-Ki Hwang, Seo Hye Park, Yun-Kyu Park, Bo-Young Jeon, Tong-Soo Kim, Hyeong-Woo Lee

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2017; 55(3): 357. CrossRef - Paleoparasitological study on the soil sediment samples from archaeological sites of ancient Silla Kingdom in Korean peninsula

Myeung Ju Kim, Min Seo, Chang Seok Oh, Jong-Yil Chai, Jinju Lee, Gab-jin Kim, Won Young Ma, Soon Jo Choi, Karl Reinhard, Adauto Araujo, Dong Hoon Shin

Quaternary International.2016; 405: 80. CrossRef - The Changing Pattern of Parasitic Infection Among Korean Populations by Paleoparasitological Study of Joseon Dynasty Mummies

Min Seo, Chang Seok Oh, Jong-Yil Chai, Mi Sook Jeong, Sung Woo Hong, Young-Min Seo, Dong Hoon Shin

Journal of Parasitology.2014; 100(1): 147. CrossRef - Paleoparasitological Studies on Mummies of the Joseon Dynasty, Korea

Min Seo, Adauto Araujo, Karl Reinhard, Jong Yil Chai, Dong Hoon Shin

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(3): 235. CrossRef - Paleoparasitological Surveys for Detection of Helminth Eggs in Archaeological Sites of Jeolla-do and Jeju-do

Myeong-Ju Kim, Dong Hoon Shin, Mi-Jin Song, Hye-Young Song, Min Seo

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2013; 51(4): 489. CrossRef - Food, parasites, and epidemiological transitions: A broad perspective

K.J. Reinhard, L.F. Ferreira, F. Bouchet, L. Sianto, J.M.F. Dutra, A. Iniguez, D. Leles, M. Le Bailly, M. Fugassa, E. Pucu, A. Araújo

International Journal of Paleopathology.2013; 3(3): 150. CrossRef