Abstract

Four cases of gastric or intestinal myiasis are reported. The cases contain 2 males (1 child 10 years old, and 1 adult 40 years old) and 2 females (1 girl 18 years old, and 1 adult 50 years old) from Minia Governorate, Southern Egypt. Three of them, including cases no. 1, 3, and 4, were gastric myiasis, and complained of offensive hematemesis of bright red blood. Minute moving worms, larvae of the fly, were found in the vomitus. On the other hand, case no. 2 had intestinal myiasis, and complained of abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The stool of case 2 was mixed with blood, and minute moving worms were observed in the stool. Endoscopy was performed to explore any pathological changes in the stomach of the patients. The larvae were collected and studied macroscopically, microscopically, and us-ing a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to identify their species. Three different types of larvae were identified. The larvae isolated from case 1 were diagnosed as the second stage larvae of Sarcophaga species, and the larvae isolated from case 2 were the third stage larvae of Sarcophaga species. On the other hand, the larvae isolated from cases 3 and 4 were diagnosed as the third stage larvae of Oestrus species.

-

Key words: Sarcophaga, Oestrus, gastric myiasis, intestinal myiasis, fly larva, SEM, endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Myiasis or infestation with fly larvae is common in domestic and wild mammals around the world. Many different species of flies can cause myiasis [

1]. In humans, myiasis is seen more frequently in rural regions where people are in close contact with pets [

2]. Infestation with fly larvae may occur when flies deposit eggs or first stage larvae on the human body or body apertures. The portion of the body affected varies with the habits and preferences of the fly species and may also depend on other factors. If eggs are deposited on the lips, within the mouth, or on food, they may be swallowed, and then develop in the stomach or intestine, giving rise to gastric or intestinal myiasis [

2]. Fifty species of dipterous larvae have been encountered from the human digestive tract, and most of the species that cause gastric and/or intestinal myiasis are facultative or ac-cidental parasites [

3].

The present study focused on gastrointestinal myiasis in patients due to

Sarcophaga spcies and

Oestrus species larvae.

Sarcophaga species are myiasis producers and their habitats make them public health suspects. They were reported to transmit some viruses, such as poliovirus, bacteria, such as

Salmonella and

Shigella, and protozoan cysts and helminth eggs, such as

Entamoeba histolytica,

Giardia lamblia,

Hymenolepis nana,

Trichuris trichiura, and

Ascaris lumbricoides [

4].

One of the

Oestrus species is the sheep botfly (

Oestrus ovis). This fly is distributed worldwide, and is prevalent in sheep-rais-ing areas. The fly deposits living larvae in the nostrils or on the eyes of sheep and goats. In humans, they may develop in the conjunctival sac or head cavities [

2].

The objective of this paper is to study the morphological identification of these larvae macroscopically and microscopically (both light and scanning electron microscopy; SEM). The study also sheds light on the clinical and endoscopical aspects of this parasitism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of cases

Four patients complaining of gastric and/or intestinal disturbance since 1-2 months have visited the out-patient clinic of the Tropical Medicine Department, Minia University Hospital seeking medical treatment. These patients showed moving worms in the stool or vomitus.

Case 1

The first case is a girl aged 18 years. She is a house-holder living in EL-Matahra village, Abu Korkas, Minia Governorate, Egypt. She complained of offensive hematemesis of bright red blood, small amount, not associated with melena. This patient suffered from minute moving worms with the vomitus since 2 months before.

Case 2

The second case is a male child aged 10 years who resides in a suburban region in Dair-Mawas city, Minia Governorate, Egypt. He visited the out-patient clinic with complaints of colicky abdominal pain, particularly on the supra-pubic region. Moreover, he suffered from loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting. He also suffered from intermittent attack of diarrhea and stool mixed with blood for 2 weeks (brownish red in color). Additionally, moving worms were seen in his stool.

Case 3

The third case is an adult male aged 40 years. He resides in a rural area in Tala village, Minia Governorate, Egypt. He is working as a shepherd in close contact with goats and sheep. He was admitted to the Tropical Medicine Department with complaints of abdominal distention and abdominal pain, particularly on the epigastric region. He also complained of loss of appetite and suffered from repeated attack of nausea and vomiting. Some moving worms were seen in his vomitus. He suffered from these symptoms for about 2 months. The patient mentioned that he accidentally swallowed 1 adult fly about 6 months before visiting the hospital.

Case 4

The fourth case is a woman of 50 years of age. She was admitted to the hospital with complaints of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Her vomitus 1 day before visiting the hospital contained worms. She mentioned that she suffered from these symptoms for about 7 months.

Methods of examinations

The 4 patients were asked to fill a questioner (age, occupation, residence, history of contact with animals, and standard of living). Complete medical examination, including the pulse rate, blood pressure, and temperature, and examination of the head, neck, chest, and abdomen, were done in the out-patient clinic. Gastroscopy preparation with Dormicum IV2 cc was performed for the patients in the Tropical Medicine Endoscopic Unit at Minia University Hospital. The vomit specimens, approximately 40 g, or stool specimens containing "worms" were sent to the reference Parasitology Laboratory, College of Medicine, Minia University, Minia, Egypt for identification.

In the Parasitology Laboratory, approximately 10-15 larvae were recovered from the vomitus or stool. Subsequently, the larvae separated were subjected to the following 3 kinds of examinations:

Macroscopic examination: By the naked eyes for identifying the color and shape, and to measure the dimensions of the larvae.

Microscopic examination: One larva from each sample was collected and cleared in a solution of 10% potassium hydroxide [

5]. The anterior and the posterior parts of most larvae were prepared for whole mount for identification of the anterior and the posterior spiracles.

SEM examination: Two maggots from each sample were prepared for SEM following the method described by Hayat [

6]. The larvae were identified according to the keys provided by Greenberg [

4].

RESULTS

The clinical examination for the 4 cases revealed that the pulse rate was normal and regular. The blood pressure and the temperature were also normal. Local examination of the head, neck, and chest were unremarkable. Local abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness in the epigastric region and lower quadrants, but there was no organomegaly or palpable masses.

Gastroendoscopic findings

Examination of the esophagus showed healthy mucosa with competent cardia. Normal intact gastric rugae and the lasting gastric juice was a few ml, watery, and clear. The mucosa of the antrum was mottled with hyperemia, regular active pylorus, and normal duodenal mucosa. Antral gastritis was marked in all cases except case 2. Minute moving worms were seen sticking to the gastric mucosa of the antrum.

Parasitological findings

Macroscopic findings

Three different types of larvae were isolated. The larvae isolated from case 1 were the second stage larvae of Sarcophaga species. The larvae isolated from case 2 were the third stage larvae of Sarcophaga species. On the other hand, the larvae isolated from cases 3 and 4 were the third stage larvae of Oestrus species.

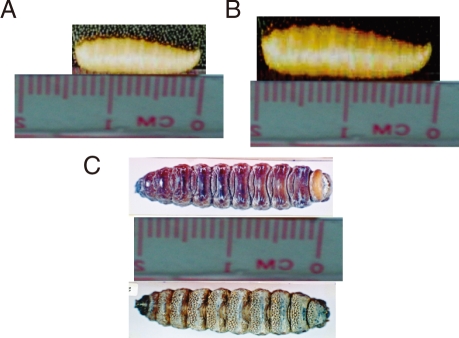

The second stage larvae of

Sarcophaga species were conical in shape and creamy white in color, and measured 13-14 mm in length and about 3 mm in width (

Fig. 1A). The third stage lar-vae of

Sarcophaga species were different from the second stage larvae in the sense that they were grayish in color and measured 18-19 mm in length and about 4 mm in width (

Fig. 1B). The third stage larvae of

Oestrus species were dark brown in color, spindle in shape, and segmented. They measured 20-21 mm in length and about 6 mm in width. The dorsal surface was convex and smooth, while the ventral surface was spiny (

Fig. 1C). The body of all types of larvae was pointed anteriorly and progressively widened posteriorly.

Light microscopic findings

The second stage larvae of

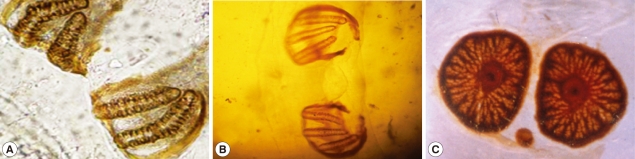

Sarcophaga species closely resembled those of the third stage larvae with the exception of posterior spiracles.The larvae were subcylindrical in cross-sections with a flattened ventral surface, truncated posteriorly, and tapering toward the anterior extremity. The posterior end was narrowed with a pit-like depression, where the posterior spiracles are located. It ends with prominent bifid anal swellings or cerci. Body segments were banded with transverse spinous swellings. The anterior end was attenuated and had a pair of projecting papillae. Extending from the lateral surfaces of the second segment, the anterior spiracles were small and fan-like structures carrying from 7-10 branches and each branch ending with a round spiracle as shown in

Fig. 2.

The posterior surface of the anal segment had a distinct cavity, and contained posterior spiracles which are a characteristic feature for differentiation as shown in

Fig. 3. In the second stage larvae of

Sarcophaga species, the posterior spiracles consisted of 2 elongate slits each surrounded by an incomplete sclerotized peritreme. In the third stage larvae of

Sarcophaga species, the posterior spiracles are located near each other and each plat was formed of widely opened peritreme with a very indistinct button (

Fig. 3A). Each plate contained of 3 elongate slits. The median one was straight, while the lateral ones were curved anteriorly (

Fig. 3B). In

Oestrus species, each plate of the posterior spiracles was surrounded by a complete sclerotized peritreme (

Fig. 3C). Its slits were indistinct in the form of several small pores and a centrally located button.

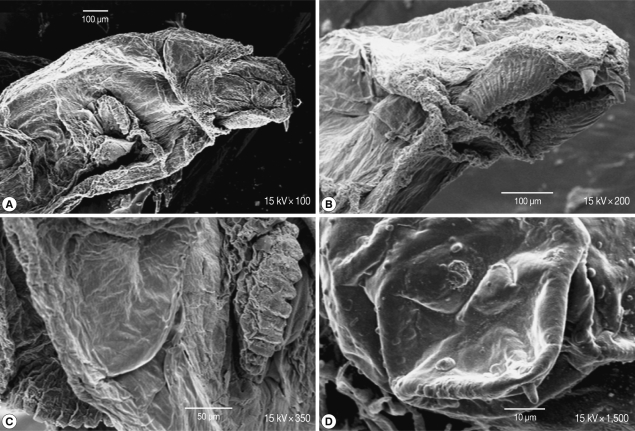

Scanning of the second stage larvae of

Sarcophaga species showed that mouth hooks were smooth in outline. The mouth vestibule was pear-shaped. The sides of the cheek had lateral striations that were directed laterally and upwards (

Fig. 4A, B). The anterior spiracles have 10 finger-like openings (

Fig. 4C). The posterior spiracles were located in a deep cavity and each contains 2 elongated spiracular opening. At the posterior end, 6 pairs of papillae were observed, 2 pairs dorsal, 2 ventral, and 1 on each side of the posterior end (

Fig. 4D).

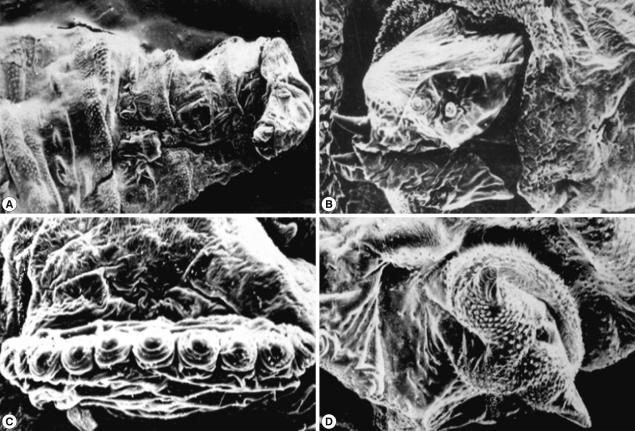

Scanning of the third stage larvae of

Sarcophaga species (

Fig. 5) showed that the anterior end had a wide and strongly spined vestibular opening through which a longitudinally striped structure, ending in a curved sharp hook, protruded on each side (

Fig. 5A). The dorsolateral aspect of each of these structures was provided with 2 anterior and 2 posterior processes (

Fig. 5B). The anterior spiracles extended laterally from the second segment (

Fig. 5C). Each of the 12 finger-like processes ended with more or less circular spiracle openings. The posterior end was surrounded by more pronounced spines (

Fig. 5D). It was provided with 2 anal cerci and 8-10 pedunculated papillae. The posterior spiracles were not visualized since they were located in a very deep pit.

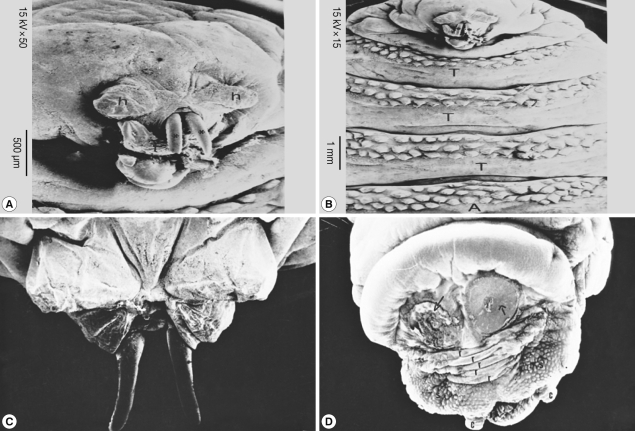

SEM of the third stage larvae of

Oestrus species is shown in

Fig. 6. The top view of the ventral surface of the larvae showed that the first segment (head) beared 2 ventrally curved hooks with pointed ends (

Fig. 6A). The oral hooks extruded from the mouth orifice lying between a tongue-like process ventrally and 2 horn-like structures dorsally. The head was followed by 3 thoracic rings, with 3 regular rows of single-ended and caudally projected spines (

Fig. 6B). The dorsal view of the anterior part of the larvae showed 2 protruded oral hooks and the extremity characterized by its butterfly shape (

Fig. 6C). The posterior spiracles appeared strongly sclerotized surrounding the outlet of the respiratory canal completely, followed by 5 anal rides and 2 caudal swelling (

Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

Myiasis is infestation of body tissues by larvae of several fly species of veterinary and medical interests [

1]. This disease occurs predominantly in rural areas, and is associated with poor hygienic practices and low educational levels [

2]. In our report, all patients were residing in rural areas, and had low standards of living. The 40-year-old adult male was working as a shepherd in close contact with goats and sheep. Also the woman (50-year-old) was a housewife rising goats and sheep at home.

In general, it is uncommon to encounter dipterous fly maggots in human feces in Egypt. However, in 1963, Atal and Dubey [

7] recorded intestinal myiasis due to

Sarcophaga species. Also, in 1965, Zupt [

8] found cases of gastrointestinal myiasis caused by flies that belonged to

Sarcophaga species [

8]. Similarly, in 1978, Mandour and Omran [

9] reported a case of intestinal myiasis accompanied with pruritus ani in a Sudanese male in Khartoum. The present study is the first to record a case of parasitic infections that caused gastritis associated with gastric fold swelling, erosions, and ulcers. One case of intestinal myiasis caused by flies belonging to

Sarcophaga species (the second or third stage larvae) was detected [

9]. This case com-plained of abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The stool of that case was mixed with blood, and minute moving worms were observed in the stool.

Flies belonging to the genus

Oestrus generally cause myiasis in the head cavities in animals, but rarely cause gastrointestinal myiasis in humans [

2,

8]. To the best of our knowledge, gastro-intestinal myiasis caused by

Oestrus spp. in animals or humans has not been reported in Egypt. Swallowing the fly accidentally by the patient without chewing may have enabled the first stage larvae to reach the stomach.

In cases 3 and 4,

Oestrus species larvae cluged to the gastric wall and grew until they reached the third stage larvae without being digested in the stomach in about 10 months. It should be emphasized that the development of the first stage larvae to the third stage larvae occurs in about 10 months [

2]. The three cases of gastric myiasis was complaining of offensive hematemesis of bright red blood. Minute moving worms were found in the vomitus. Accordingly, it can be expected that the patients' digestive functions might have been disturbed at least 10 months before admission to the hospital. The patient did not apply to a hospital neglecting his health condition probably due to his low socioeconomic status. Since the patient observed larvae at the beginning of vomiting, the location of myiasis was considered to be in the stomach. It was also surprising to see minute moving worms sticking to the gastric mucosa of the antrum through gastroscopic examination.

Myiasis of different organs has been reported in various regions of the world. Following diagnosis and treatment of the patients, intestinal myiasis can be improved completely with cessation of maggots in the stool. The large grayish flesh fly belonging to the family Sarcophagidae has a nearly world wide distribution [

10]. Two of our cases were caused by the Sarcophagidae. This is because

Sarcophaga species are generally present in rural and urban environments and commonly found in houses and indoor dwellings. The study carried out in 1999 by Habib and Ahmed [

11] in Minia Governorate confirmed this.

Identification of the species of maggots prior to treatment is important since not all types of myiasis are benign [

12]. The present work focused on an ordinary microscopy for identification of the larvae. However, SEM of the anterior end of the maggots was carried out as a supportive measure to illustrate some important features that may constitute useful criteria in the larval identification and species differentiation. Among our cases, SEM showed remarkable differences in the anterior end of

Sarcophaga species (lateral striations on the side of the cheeks) particularly in cases 1 and 2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Prof. Nabil Shokrany Gabr, Head of the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Minia University, Egypt, for his continuous advice in technical procedures. Thanks are extended to Prof. Nawras M. Mowafy, Professor of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Minia University for her guiding us through the technical intricacies as well as writing this paper. The authors would also like to thank Prof. Refaat M. A. Khalifa, Professor of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Assuit University for continuous advice through the technical procedures especially for SEM.

References

- 1. Yilmaz H, Kotan C, Akdeniz H, Buzğan T. Gastric myiasis due to Oestrus species in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report. East J Med 1999;4:80-81.

- 2. Markel EK, Voge M, John DT. Medical Parasitology. 1992, 7th ed. Philadelphia, USA. W.B. Saunders; pp 353-358.

- 3. Shazia MT, Anjum S, Yousuf MJ. Systematics and population of sarcophagid flies in Faisalabad (Pakistan). Int J Agricult Biol 2006;8:809-811.

- 4. Greenberg B. Flies and Disease. Ecology, classification and biotic association. 1971, Vol. 1:Princeton, New Jersey, USA. Princeton University Press; pp 163-190.

- 5. Khalifa RMA, Mowafy NME. Light and scanning electron microscopical identification of sarcophagid larva causing intestinal myiasis. Egypt J Med Sci 1997;18:235-243.

- 6. Hayat MA. Principles and Techniques of Electron Microscopy. 1981, Vol. 1:2nd ed. New Jersey, USA. University Park Press.

- 7. Atal PR, Dubey DC. Intestinal myiasis with accompanying helminthic infestations. J Indian Med Assoc 1963;41:403-405.

- 8. Zumpt F. Myiasis in Man and Animals in the Old World. 1965, London, UK. Butterworth and Co..

- 9. Mandour AM, Omran LA. A case report of intestinal myiasis accompanied with pruritus ani. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 1978;8:105-108.

- 10. Das A, Pandey AD, Medan M, Asthana AK, Gautam A. Accidental intestinal myiasis caused by genus Sarcophaga. Indian J Med Microbiol 2010;28:176-178.

- 11. Habib SR, Ahmed AK. An initial study of insect succession and carrion decomposition in various environments in Minia Governorate. Egypt J Forensic Sci Appl Toxicol 2009;9:107-120.

- 12. Singh TS, Rana D. Urogenital myiasis caused by Megaselia scalaris (Diptera: Phoridae): a case report. J Med Entomol 1989;26:228-229.

Fig. 1Macroscopic examination of the 3 different types of larvae. The second stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp. (A), the third stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp. (B), and the third stage larvae of Oestrus sp. (C).

Fig. 2Anterior respiratory spiracles. These are small and fan-like structures carrying from 7-10 branches.

Fig. 3Posterior respiratory spiracles. In the second stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp., the post spiracles consist of 2 elongate slits (A). In the third stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp., the post spiracles have 3 elongate slits (B). In Oestrus sp., its slits are indistinct in the form of several small pores and centrally located button.

Fig. 4SEM of the second stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp. Mouth hooks are smooth in outline. Lateral striations are on the side of the cheeks (A, B). The anterior spiracles have 10 finger-like openings (C). Posterior spiracles have 2 elongated spiracular opening (D).

Fig. 5SEM of the third stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp. The anterior end has spined vestibular opening (A). The dorsolateral aspect is provided with 2 anterior and posterior processes (B). The posterior end of anterior spiracles (C) is surrounded with 2 anal cerci (D).

Fig. 6SEM of the third stage larvae of Oestrus sp. The first segment (head) bears 2 ventrally curved hooks with pointed ends (A). Three thoracic rings, with 3 regular rows of single-ended caudally projected spines are seen (B). Two oral hooks (C) and 2 caudal swellings (D) are visible. T, thorax; A, abdomen.