Abstract

We encountered an indigenous case of intestinal capillariasis with protein-losing enteropathy in the Republic of Korea. A 37-year-old man, residing in Sacheon-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, admitted to the Gyeongsang National University Hospital (GNUH) due to long-lasting diarrhea, abdominal pain, anasarca, and weight loss. He recalled that he frequently ate raw fish, especially the common blackish goby (Acanthogobius flavimanus) and has never been abroad. Under the suspicion of protein-losing enteropathy, he received various kinds of medical examinations, and was diagnosed as intestinal capillariasis based on characteristic sectional findings of nematode worms in the biopsied small intestine. Adults, juvenile worms, and eggs were also detected in the diarrheic stools collected before and after medication. The clinical symptoms became much better after treatment with albendazole 400 mg daily for 3 days, and all findings were in normal range in laboratory examinations performed after 1 month. The present study is the 6th Korean case of intestinal capillariasis and the 3rd indigenous one in the Republic of Korea.

-

Key words: Capillaria philippinensis, intestinal capillariasis, indigenous case, protein-losing enteropathy

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal capillariasis, caused by

Capillaria philippinensis, was first recognized in an autopsy case occurred in Ilocos Norte, Luzon Island, the Philippines [

1,

2]. Since the first case report in the Philippines, this nematode infections have been subsequently reported from other parts of Asia (Thailand, Japan, Iran, Taiwan, Egypt, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, Korea, India, and Lao PDR) [

3-

12], and even from non-endemic areas (South America) [

13]. In the Republic of Korea, total 5 cases have been reported so far. The first case, with severe emaciation and malnutrition due to long-lasting diarrhea, was found in 1991 by detecting worm sections from the biopsied intestine, and also by identifying the eggs in fecal samples [

10]. After the first case report, 1 indeginous (Namwon-si, Jeollabuk-do) and 3 imported cases (from Bali in Indonesia and Saipan Island) were added [

14-

16]. In the present study, we describe clinical and parasitological findings of an intestinal capillariasis case with protein-losing enteropathy occurred in an inland area of Korea.

CASES DESCRIPTION

A 37-year old man, residing in Sacheon-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, visited the Gyeongsang National University Hospital (GNUH) for his long-lasting diarrhea and general edema on July 2010. He had been treated at a private clinic before visiting GNUH, but symptoms aggravated gradually. At that time, the total serum protein and albumin levels were 5.0 and 2.4 g/dl, respectively, urine protein was negative, and thyroid function test was normal. In routine stool examinations, Clonorchis sinensis eggs were detected; therefore, we prescribed him praziquantel.

Ten months later, he admitted to our hospital because of persistent diarrhea, abdominal pain, general edema, and 15 kg weight loss for a year. The diarrhea was watery, but neither bloody nor mucoid. He said that he frequently ate raw fish, especially common blackish goby (Acanthogobius flavimanus) and has never been abroad. He was chronically ill-looking and emaciated at a glance. We observed tenderness around periumbilical area and general edema on physical examination. In the initial laboratory findings, the total serum protein and albumin levels were 3.7 and 1.3 mg/dl, respectively. Blood cell counts and other biochemical laboratory findings were within normal ranges. Stool examinations were negative for occult blood and parasites. Alpha1-antitrypsin clearance in 24 hr-stool increased to 150.5 ml/24 hr. The results of thyroid function test were 90.81 ng/dl of T3, 0.91 ng/dl of free T4, and 13.35 mIU/L of TSH, but all of autoantibodies such as anti-thyroglobulin, anti-TPO, TSH-receptor-Ab were negative. Synthyroid 0.05 mg was given to him for 2 weeks, but serum albumin was still low as 1.2 g/dl, and diarrhea and general edema were not improved. In the abdominal CT, there was proximal small bowel wall thickening and transient intussusception. Diffuse effacement of small bowel folds from the mid-jejunum to terminal ileum was seen at a small bowel double contrast study. There was diffuse mucosal edema and large amount of whitish exudates at the jejunum and terminal ileum. However, the lesion was not ulcerative and without mass in the whole small bowel mucosa by small bowel capsule endoscopy. Esophagogastroduodenoscopic and colonoscopic findings were non-specific except for mild mucosal edema at the terminal ileum. Blind random biopsy was performed at 10 cm and 30 cm proximal from the ileocecal valve.

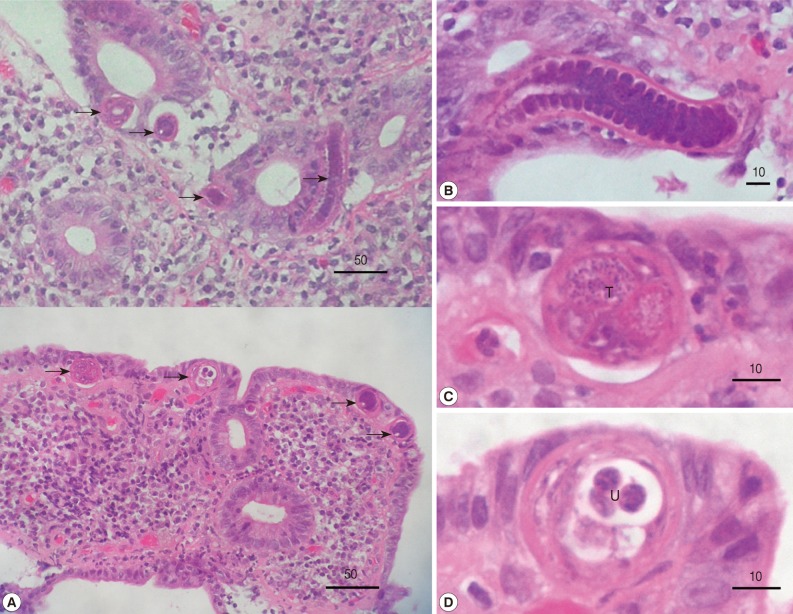

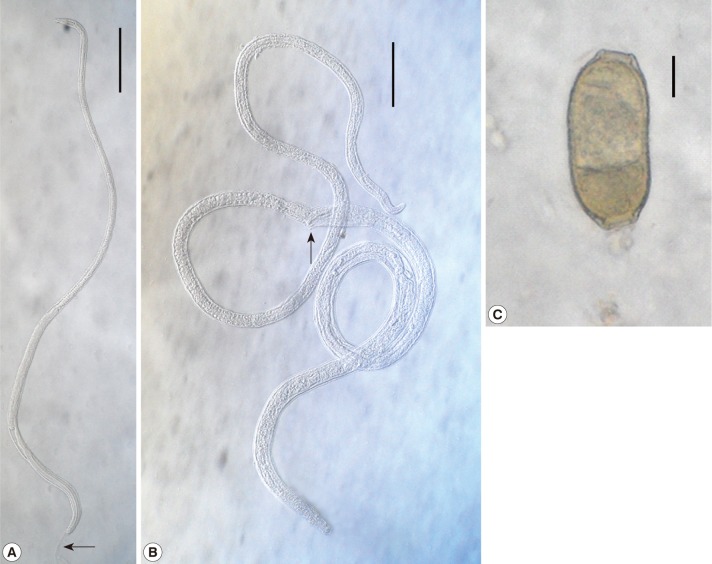

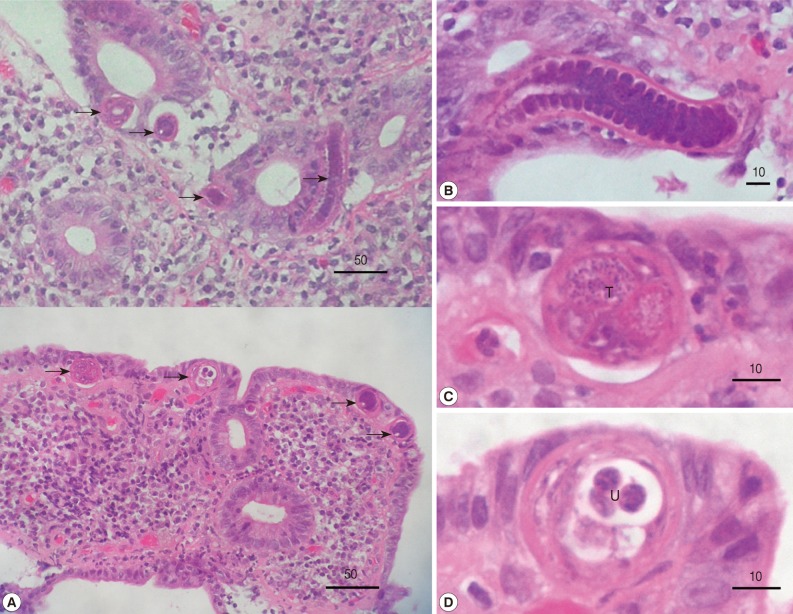

The intestinal villi were atrophic and there was an intense infiltration of plasma cells in the lamina propria. Sectioned nematode worms were seen in the epithelial layer. Some cross-sectioned worms (n=9) were 25-30 (av. 27) µm and 33-38 (35) µm in diameter, and revealed the characteristic features of

C. philippinensis (stichocytes and male and female genital organs) (

Fig. 1). We could make the diagnosis as intestinal capillariasis and prescribed albendazole 400 mg daily for 3 days. A month later, all symptoms disappeared and the total serum protein and albumin levels were normalized to 6.4 and 3.8 mg/dl, respectively.

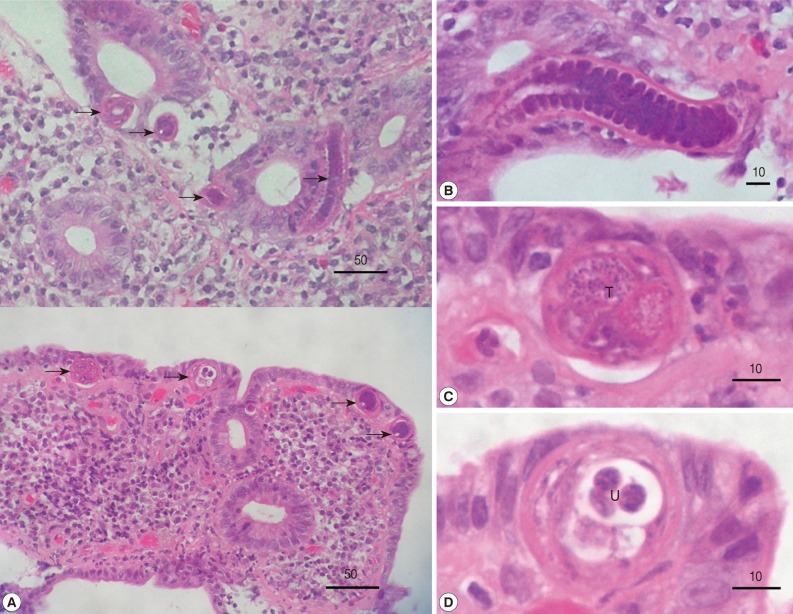

Adults and eggs of

C. philippinensis were recovered in the diarrheic stools collected before and after treatment. Male worms (n=10) were 1,770-2,150 (1,872 in average) µm long and 27.5-30.0 (28.0 in average) µm wide, and had a characteristically long esophagus (950-1,150 µm long) with a chain of stichocytes and a long spicule within a sheath (

Fig. 2A). Female worms (n=10) were 2,290-2,970 (2,556 in average) µm long and 30-38 (35 in average) µm wide, and had a long esophagus (1,150-1,450 µm long) with a chain of stichocytes and immature eggs (35-44×18-23 µm size) in the uterus. Their posterior ends were more blunt than anterior ends, and vulva openings were located posteriorly at 38-45 µm from the esophago-intestinal junction (

Fig. 2B). Mature eggs (n=5) detected in the diarrheic stools were 42.5-45.0 (av. 43.3) µm long and 20.0-21.3 (20.4) µm wide, and had characteristic mucoid plugs at both ends (

Fig. 2C).

DISCUSSION

The present study is the 6th Korean case of intestinal capillariasis and the 3rd case indigenously occurred in Korea. The outbreak place of the present case, Sacheon-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, is not so far from Namwon-si, Jeollabuk-do, in which 2 indigenous cases previously occurred [

10,

14]. These indigenous cases suggest that the life cycle of

C. philippinensis is maintained in the southern regions of the Korean peninsula, such as Namwon-si and Sacheon-si. Accordingly, studies on epidemiologic characteristics of

C. philippinensis, especially on the source of human infections, transmission modes, fish intermediate hosts, and natural reservoir (definitive) hosts, should be performed in the near future.

On the other hand, the remaining 3 cases were imported from Bali in Indonesia and Saipan Island [

14-

16]. Recently, in some Asian countries (India, Egypt, Lao PDR, Thailand, Taiwan, and the Philippines), intestinal capillariasis is regarded as the emerging and/or reemerging parasitic disease, and it's outbreaks have been frequently reported [

12,

17-

21]. Therefore, travelers going around these countries should pay attention to this nematode disease.

Protein-losing enteropathy is a complication frequently manifested in the intestinal capillariasis [

16-

18]. It is a result of direct mucosal invasion by the adult worms, which is sometimes exacerbated by the host inflammatory responses. Although the intestinal tract frequently has grossly normal appearance, histopathologic examinations of the biopsied intestines reveal villus atropy, crypt hyperplasia, and occasional infiltration of inflammatory cells [

22]. In the present study, although mild mucosal edema was observed at the terminal ileum, ulcerative or mass lesion was not found in the whole small bowel mucosa. However, in the biopsied specimens, villus atrophy, an intense infiltration of plasma cells, and sectioned nematode worms were seen in the epithelial layer. Numerous worms embedded in the intestinal mucosa may be associated with ulcerative and degenerative changes, and the protein-losing enteropathy may be provoked as a result.

Regarding the diagnosis of intestinal capillariasis, characteristic clinical symptoms, including long-lasting diarrhea, abdominal pain, severe weight loss, and low serum albumin level, may be considerable factors in the first step. A definite diagnosis can be made by detection of worms and eggs in the diarrheic stools. However, histopathologic findings of biopsied intestines, including villus atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, intense infiltration of inflammatory cells, and worm sections, may be useful as the second-step diagnostic procedure. However, the exact sampling of intestines is not easy because endoscopic examinations are not applicable to the jejunum of humans, the normal habitat of

C. philippinensis. In the present study, biopsy was performed at the terminal ileum through colonoscopy, and diagnostic clues were found in the biopsy specimens before the recovery of worms and eggs in the stool samples. Hong et al. [

14] diagnosed their case I by detection of worms and eggs in the biopsy specimens of the terminal ileum, like in our case, whereas Kwon et al. [

16] found worm sections in the biopsied jejunum. All Korean cases were definitely diagnosed by the detection of eggs and/or worms in the diarrheic stools of patients [

10,

14-

16].

The infection source of intestinal capillariasis is still obscure in Korea. Cases indigenously occurred in Namwon-si experienced consuming raw freshwater fish, i.e., several species of cyprinoid fish and rainbow trout [

10,

14]. The present case recalled that he frequently ate raw goby (

Acanthogobius flavimanus), which could be easily captured in the seashore near his residential place. However, he was mixed-infected with

C. sinensis, which is an evidence of eating raw freshwater fish also. Accordingly, some fish species, including the common blackish goby, must be the source of human infections, and this should be clarified in the near future in Korea.

References

- 1. Chitwood MB, Valesquez C, Salazar NG. Capillaria philippinensis sp. n. (Nematoda: Trichinellidae), from the intestine of man in the Philippines. J Parasitol 1968;54:368-371.

- 2. Whalen GE, Rosenberg EB, Strickland GT, Gutman RA, Cross JH, Watten RH. Intestinal capillariasis. A new disease in man. Lancet 1969;1:13-16.

- 3. Pradatsundarasar A, Pecharanónd K, Chintanawóngs C, Ungthavórn P. The first case of intestinal capillariasis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1973;4:131-134.

- 4. Mukai T, Shimizu S, Yamamoto M, Horiuchi I, Kishimoto S, Kajiyama G. A case of intestinal capillariasis. Jpn Arch Intern Med 1983;30:163-169.

- 5. Hoghooghi-Rad N, Maraghi S, Narenj-Zadeh A. Capillaria philippinensis infection in Khoozestan Province, Iran: Case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1987;37:135-137.

- 6. Chen CY, Hsieh WC, Lin JT, Liu MC. Intestinal capillariasis: Report of a case. Taiwan Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi 1989;88:617-620.

- 7. Youssef FG, Mikhail EM, Mansour NS. Intestinal capillariasis in Egypt: A case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1989;40:195-196.

- 8. Chichino G, Bernuzzi AM, Bruno A, Cevini C, Atzori C, Malfitano A, Scaglia M. Intestinal capillariasis (Capillaria philippinensis) acquired in Indonesia: A case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1992;47:10-12.

- 9. el Hassan EH, Mikhail WE. Malabsorption due to Capillaria philippinensis in an Egyptian woman living in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992;86:79.

- 10. Lee SH, Hong ST, Chai JY, Kim WH, Kim YT, Song IS, Kim SW, Choi BI, Cross JH. A case of intestinal capillariasis in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993;48:542-546.

- 11. Kang G, Mathan M, Ramakrishna BS, Mathai E, Sarada V. Human intestinal capillariasis: first report from India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994;88:204.

- 12. Soukhathammavong P, Sayasone S, Harimanana AN, Akkhavong A, Thammasack S, Phoumindr N, Choumlivong K, Choumlivong K, Keoluangkhot V, Phongmany S, Akkhavong K, Hatz C, Strobel M, Odermatt P. Three cases of intestinal capillariasis in Lao People's Democratic Republic. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;79:735-738.

- 13. Dronda F, Chaves F, Sanz A, Lopez-Velez R. Human intestinal capillariasis in an area of nonendemicity: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17:909-912.

- 14. Hong ST, Kim YT, Choe G, Min YI, Cho SH, Kim JK, Kook J, Chai JY, Lee SH. Two cases of intestinal capillariasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1994;32:43-48.

- 15. Lee SH, Rhee PL, Lee JH, Lee KT, Le JK, Sim SG, Lee SK, Kim JJ, Ko KC, Paik SW, Rhee JC, Choi KW, Lee NY, Cho SL, Ryu KH. A case of intestinal capillariasis: fourth case report in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol 1999;34:542-546. (in Korean).

- 16. Kwon Y, Jung HY, Ha HK, Lee I. An imported case of intestinal capillariasis presenting as protein-losing enteropathy. Korean J Pathol 2000;34:235-238. (in Korean).

- 17. Vasantha PL, Girish N, Leela KS. Human intestinal capillariasis: A rare case report from non-endemic area (Andhra Pradesh, India). Indian J Med Microbiol 2012;30:236-239.

- 18. Attia RA, Tolba ME, Yones DA, Bakir HY, Eldeek HE, Kamel S. Capillaria philippinensis in Upper Egypt: has it become endemic? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86:126-133.

- 19. Saichua P, Nithikathkul C, Kaewpitoon N. Human intestinal capillariasis in Thailand? World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:506-510.

- 20. Lu LH, Lin MR, Choi WM, Hwang KP, Hsu YH, Bair MJ, Liu JD, Wang TE, Liu TP, Chung WC. Human intestinal capillariasis (Capillaria philippinensis) in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;74:810-813.

- 21. Belizario VY, de Leon WU, Esparar DG, Galang JM, Fantone J, Verdadero C. Compostela Valley: A new endemic focus for capillariasis philippinensis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2000;31:478-481.

- 22. Cross JH. In Farthing MJG, Keusch GT, Wakelin D eds, Capillaria philippinensis and Trichostrongylus orientalis. Enteric infection 2. Intestinal helminthes. 1995, London, UK. Chapman & Hall Medical; pp 151-164.

Fig. 1(A) Histopathologic findings, including atrophic intestinal villi, intense infiltration of plasma cells in the lamina propria, and sectioned worms (arrow marks), are seen in biopsy specimens of the small intestines. (B-D) Magnified views of sectioned worms. (B) A longitudinal section of an esophageal level with stichocytes. (C) Cross-section of the testis (T) level. (D) Cross-section of the uterus (U) level with sectioned larvae. All scale bar in µm.

Fig. 2Adult worms and an egg of Capillaria philippinensis collected from the diarrheic stools of the patient. (A) Male worm, 1,872×28.0 µm in average size, showing the characteristically long esophagus with a chain of stichocytes and a long spicule within a sheath (arrow mark). Scale bar=200 µm. (B) Female worm, 2,556×35 µm in average size, having a long esophagus with a chain of stichocytes and a vulva opening (arrow mark) located posteriorly at about 42 µm from the esophago-intestinal junction. Scale bar=100 µm. (C) A mature egg, 43.3×20.4 µm in size, having characteristic mucoid plugs at both ends. Scale bar=10 µm.