Abstract

Fascioliasis is a zoonotic infection caused by Fasciola hepatica or Fasciola gigantica. We report an 87-year-old Korean male patient with postprandial abdominal pain and discomfort due to F. hepatica infection who was diagnosed and managed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with extraction of 2 worms. At his first visit to the hospital, a gallbladder stone was suspected. CT and magnetic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed an intraductal mass in the common bile duct (CBD) without proximal duct dilatation. Based on radiological findings, the presumed diagnosis was intraductal cholangiocarcinoma. However, in ERCP which was performed for biliary decompression and tissue diagnosis, movable materials were detected in the CBD. Using a basket, 2 living leaf-like parasites were removed. The worms were morphologically compatible with F. hepatica. To rule out the possibility of the worms to be another morphologically close species, in particular F. gigantica, 1 specimen was processed for genetic analysis of its ITS-1 region. The results showed that the present worms were genetically identical (100%) with F. hepatica but different from F. gigantica.

-

Key words: Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica, sheep liver fluke, bile duct cancer, molecular diagnosis, ITS-1

INTRODUCTION

There has been an increased risk of

Fasciola hepatica infection worldwide in the last decade [

1]. It is recently reported that 2.5 million people are infected with this fluke in 61 countries and more than 180 million people are at risk [

1].

F. hepatica occurs mainly in sheep-rearing areas of temperate climates, particularly in parts of Central and South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East [

2]. In Korea, a few human cases have been reported since the first case was documented in 1976 [

3].

Humans can acquire the infection by consuming aquatic vegetables including water cress and also raw liver of an infected animal [

2]. Infections are also thought possible by drinking contaminated water containing viable metacercariae of

F. hepatica. Acute symptoms usually begin within 8-12 weeks after metacercarial ingestion [

2]. The early phase of migration through the liver is often associated with fever, right upper quadrant pain, and hepatomegaly. Other symptoms include jaundice, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, cough, and urticaria [

4]. Marked peripheral eosinophilia is almost always accompanied [

4]. Thus, the diagnosis of fascioliasis should be considered in patients with abdominal pain and hepatomegaly accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia.

We recently experienced a F. hepatica patient who was clinically diagnosed as an intraductal cholangiocarcinoma before performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). During ERCP, 2 F. hepatica worms were removed from the common bile duct (CBD). Here, we report our case and share the experience.

CASE RECORD

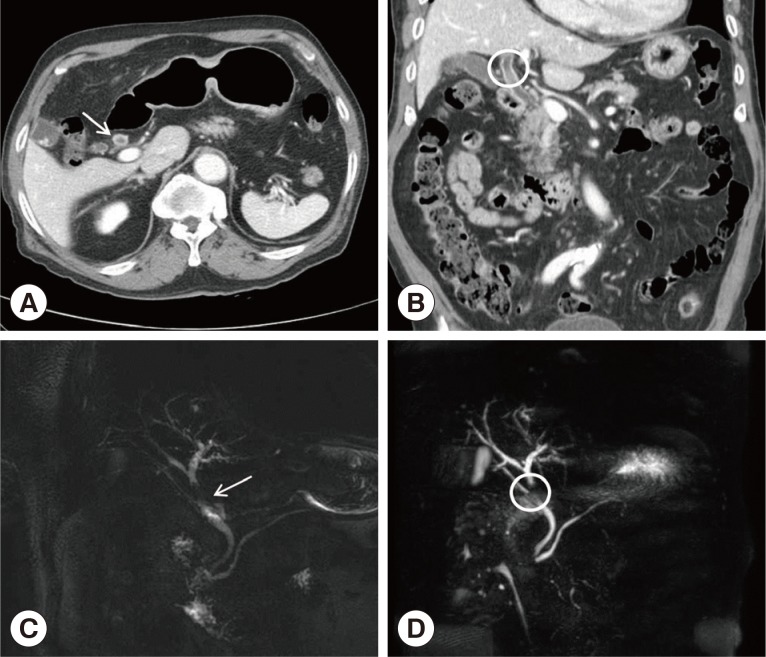

An 87-year-old man who had postprandial abdominal pain and discomfort for several months was referred to us for evaluation. CT revealed intraductal soft tissue in the CBD without definite evidence of ductal obstruction and segmental bile duct wall thickening, which suggested a bile duct cancer (

Fig. 1A, B). For differential diagnosis, magnetic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed, which showed segmental wall thickening with papillary filling defect at the CBD, with minimal upstream duct dilatation (

Fig. 1C, D). The laboratory findings were within normal limits, except for peripheral eosinophilia (1,091 eosinophils per mm

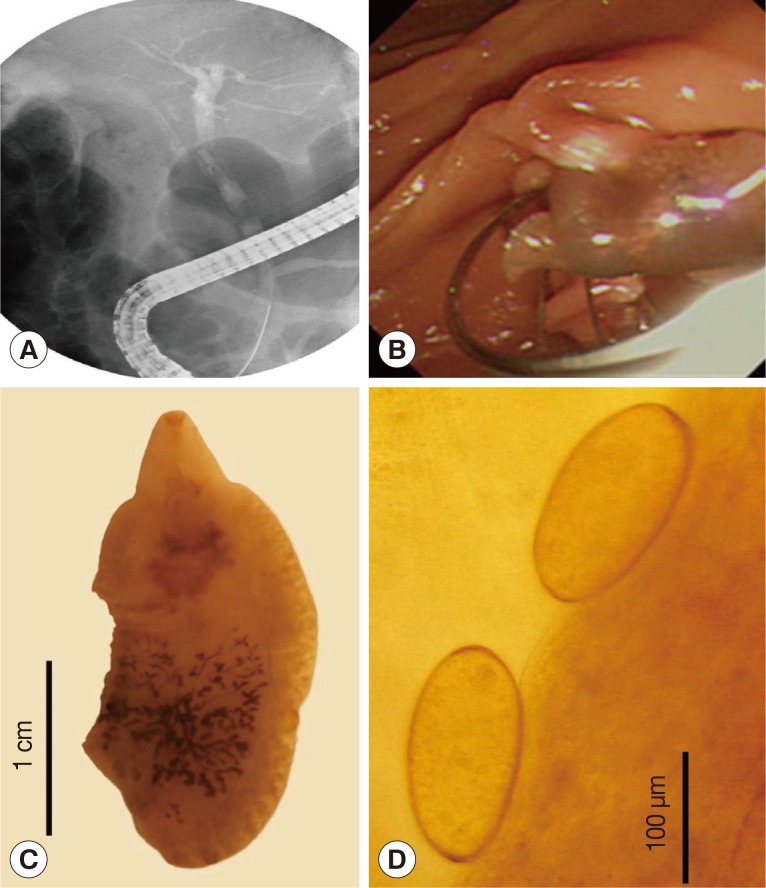

3, 13.3% of the total WBC). To obtain tissue for pathological diagnosis, ERCP was done which demonstrated a small filling defect of the mid-CBD (

Fig. 2A). After endoscopic sphincterotomy, 2 living leaf-like parasites were removed from the CBD using a basket (

Fig. 2B). At that time, he was diagnosed presumptively as

Clonorchis sinensis infection. Thus, he took praziquantel at 3 doses of 25 mg/kg (total 75 mg/kg) for 1 day. However, consequent detailed morphological examinations revealed that the parasites recovered were not

C. sinensis but

F. hepatica. The adult flukes (

Fig. 2C) were 2.6×1.2 cm in average size (n=2). The eggs (

Fig. 2D) recovered from the uterus of a worm were 135-145×65-80 µm in size (n=5). These morphological findings were compatible with those of

F. hepatica [

5].

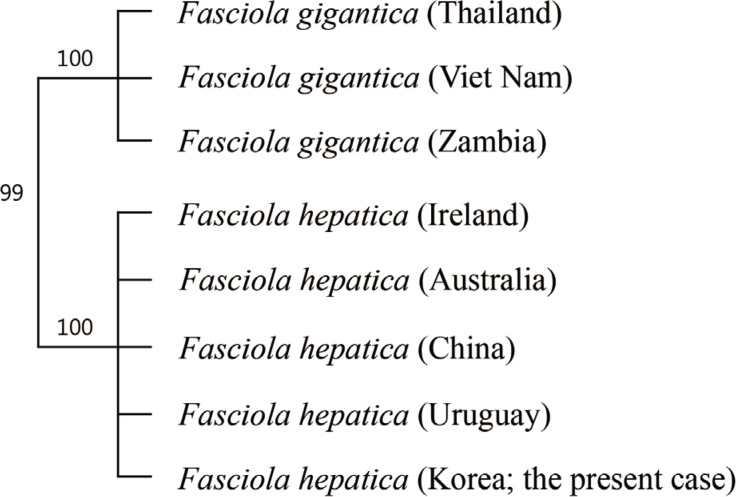

In order to provide genetic diagnosis, 1 of the 2 specimens was processed for sequencing of its internal transcribed spacer-1 (ITS-1) region. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. ITS-1 fragment (about 1,000 bp) was amplified by PCR using a set of 5'-TTGCGCTGATTACGTCCCTG-3' and 5'-TTG- GCTGCGCTCTTCATCGAC-3' as forward and reverse primers, respectively [

6]. The reaction was done in a total volume of 20 µl containing 10 µl PCR premix, 1 µl of each primer (0.05 pM), 1 µl of genomic DNA, and 7 µl H

2O. Reaction cycles consisted of an initial denaturation at 95℃ for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95℃ for 30 sec, annealing at 62℃ for 30 sec and extension at 72℃ for 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 72℃ for 10 min. A phylogenetic tree was established based on ITS-1 gene sequences to show the relationships among

F. hepatica,

F. gigantica, and our sample (576 bp) using the Geneious 6.0.3 software (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). The phylogenetic tree revealed a 100% identity of our specimen with 4 different geographical isolates of

F. hepatica (Ireland, Australia, China, and Uruguay) and 99% identity with 3 geographical isolates of

F. gigantica (Thailand, Vietnam, and Zambia) (

Fig. 3). There were nucleotide differences at 6 loci of ITS-1 region between

F. hepatica and

F. gigantica, and our specimen was exactly compatible with

F. hepatica (

Table 1).

When the patient came back to the outpatient clinic 2 weeks later, he had no symptoms at all and eosinophilia disappeared. Although praziqantel is known to be ineffective against F. hepatica infection, we did not prescribe triclabendazole because of no symptoms remained in this patient.

DISCUSSION

There are often delays in the diagnosis of fascioliasis. In a review article, patients with hepatic phase fascioliasis had symptom durations ranging from 3 to 144 weeks before the diagnosis was made (mean 25 weeks) [

7]. In patients with biliary phase fascioliasis, the delay was even longer (symptomatic during 1-208 weeks; mean 64 weeks). The diagnosis can be established by identifying eggs in stool, duodenal aspirates, or bile specimens. Eggs are not detected in stool during the acute phase of infection or in the setting of ectopic fascioliasis. In such cases, diagnosis may require serology and examination of surgical specimens following removal of the parasite [

8].

In the present case, we performed stool examinations but there were no eggs probably due that the patient was in an acute phase of infection. Because the biliary phase of

F. hepatica infection is usually asymptomatic, our patient was a rare case who presented with biliary obstruction [

9]. The CT images are sometimes confused with malignancy or stones, similar to our case [

10]. We made a tentative diagnosis as an intraductal tumor or radiolucent stone, even after CT and MRCP. In Korea, there were some cases of fascioliasis which mimicked cholangiocarcinoma [

11]. Unlike intraductal cholangiocarcinoma, our patient had normal liver functions even though an intraductal mass with mild biliary obstruction was seen on radiological examinations.

Our specimens were morphologically close to

F. hepatica rather than to

F. gigantica. The 2 worms recovered were stout and short, different from

F. gigantica which is thin and elongated [

5]. Moreover, the rear end of the testis was located posteriorly, and thus the post-testicular length was not long, which is consistent with

F. hepatica [

5]. The egg size was also compatible with

F. hepatica, and smaller than that of

F. hepatica [

5].

Sequencing of ITS-1 region of the worm recovered from the present case revealed complete identity (100%) with

F. hepatica reported from 4 different geographical localities. However, its similarity with 3 different geographical isolates of

F. gigantica was also very high, up to 99%. This strongly suggests that

F. hepatica and

F. gigantica are genetically very close species. The only difference was at 6 variable sites of nucleotide sequence (no. 92, 219, 309, 403, 481, and 501), and our specimen was exactly the same as

F. hepatica (

Table 1).

Because fascioliasis is increasingly encountered worldwide, physicians should be aware of this disease in non-endemic areas such as Korea as well as in high endemic areas such as Portugal, the Nile delta, northern Iran, parts of China, and the Andean highlands of Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru [

2]. Several kinds of medications have been used to treat fascioliasis with varying successes. It is well known that fascioliasis responds poorly to praziquantel. A first-line treatment is a single dose (10 mg/kg) of triclabendazole, a well-tolerated benzimidazole used in daily practices that is highly effective against mature and immature flukes of

F. hepatica [

12].

Notes

-

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- 1. Haseeb AN, el-Shazly AM, Arafa MA, Morsy AT. A review on fascioliasis in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 2002;32:317-354.

- 2. Liu D, Zhu XQ. Fasciola. In Liu D ed, Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens. Boca Raton, Florida, USA. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013, pp 343-351.

- 3. Kim YH, Kang KJ, Kwon JH. Four cases of hepatic fascioliasis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Hepatol 2005;11:169-175.

- 4. Chan CW, Lam SK. Five diseases caused by liver flukes and cholangiocarcinoma. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1987;1:297-318.

- 5. Miyazaki I. An Illustrated Book of Helminthic Zoonoses. Tokyo, Japan. International Medical Foundation of Japan; 1991, pp 51-60.

- 6. Mahami-Oskouei M, Dalimi A, Forouzandeh-Moghadam M, Rokni MB. Molecular identification and differentiation of Fasciola isolates using PCR-RFLP method based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS1, 5.8S rDNA, ITS2). Iran J Parasitol 2011;6:35-42.

- 7. Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S. Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4899-4904.

- 8. Prociv P, Walker JC, Whitby M. Human ectopic fascioliasis in Australia: first case reports. Med J Aust 1992;156:349-351.

- 9. Kiladze M, Chipashvili L, Abuladze D, Jatchvliani D. Obstruction of common bile duct caused by liver fluke-Fasciola hepatica. Sb Lek 2000;101:255-259.

- 10. Dias LM, Silva R, Viana HL, Palhinhas M, Viana RL. Biliary fascioliasis: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:616-619.

- 11. Cho SY, Seo BS, Kim YI, Won CK, Cho SK. A case of human fascioliasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1976;14:147-152.

- 12. Millan JC, Mull R, Freise S, Richter J. Triclabendazole Study Group. The efficacy and tolerability of triclabendazole in Cuban patients with latent and chronic Fasciola hepatica infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;63:264-269.

Fig. 1CT and MRCP findings of intraductal lesion of the present patient. (A) CT showing the segmental common hepatic duct wall thickening (white arrow). (B) Intraductal soft tissue lesion in the common hepatic duct without definite evidence of duct obstruction (white circle). (C, D). MRCP revealing intraductal filling defect of the mid-portion of the common bile duct (white arrow and circle).

Fig. 2ERCP findings (A, B), Fasciola hepatica adult worm (C), and eggs (D). (A) ERCP showing a linear filling defect within the mid-portion of the common bile duct (CBD). (B) After endoscopic sphincterotomy, a live F. hepatica worm could be removed. (C) An adult worm of F. hepatica recovered from this patient, damaged partially. (D) Two eggs of F. hepatica extracted from the uterus of a worm from this patient.

Fig. 3A phylogenetic tree based on ITS-1 gene sequences exploring the relationships among our specimen (F. hepatica; Korea), F. hepatica (GenBank), and F. gigantica (GenBank). Note that our specimen and F. hepatica in GenBank have 100% homology, whereas ours and F. gigantica have 99% similarity.

Table 1.Nucleotide comparison at 6 variable sites of ITS-1 region of Fasciola spp. from Korea and 7 other countries

Table 1.

|

Species |

Locality (GenBank Accession no.) |

Nucleotide sites of ITS-1 region

|

|

92 |

219 |

309 |

403 |

481 |

501 |

|

F. hepatica

|

Ireland (AB514850) |

T |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

|

Australia (AB514949) |

T |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

|

China (AB514851) |

T |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

|

Uruguay (AB514847) |

T |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

|

F. hepatica

|

Korea |

T |

C |

A |

C |

T |

C |

|

F. gigantica

|

Thailand (AB514853) |

C |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

|

Vietnam (AB514856) |

C |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |

|

Zambia (AB514855) |

C |

T |

T |

T |

A |

T |