Abstract

Arthrostoma miyazakiense (Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae) is a hookworm species reported from the small intestines of raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in Japan. Five Korean raccoon dogs (N. procyonoides koreensis) caught from 2002 to 2005 in Jeollanam-do (Province), a southeastern area of South Korea, contained helminth eggs belonging to 4 genera (roundworm, hookworm, whipworm, and Capillaria spp.) and cysts of Giardia sp. in their feces. Necropsy findings of 1 raccoon dog revealed a large number of adult hookworms in the duodenum. These hookworms were identified as Arthrostoma miyazakiense based on the 10 articulated plates observed in the buccal capsule and the presence of right-sided prevulval papillae. Eggs of A. miyazakiense were 60-65 × 35-40 µm (av. 62.5 × 35 µm), and were morphologically indistinguishable from those of Ancylostoma caninum. The eggs were cultured to infective 2nd stage larvae via charcoal culture, and 100 infective larvae were used to experimentally infect each of 3 mixed-bred puppies. All puppies harbored hookworm eggs in their feces on the 12th day after infection. This is the first report thus far concerning A. miyazakiense infections in raccoon dogs in Korea, and the first such report outside of Japan.

-

Key words: Arthrostoma miyazakiense, hookworm, raccoon dogs

INTRODUCTION

Arthrostoma miyazakiense, a hookworm species which is detected in the small intestines of raccoon dogs, is not equipped with teeth in the buccal capsule. Because of this, the species was originally given the name

Necator miyazakiensis (

Nagayoshi, 1955). The nematode parasite, however, was redescribed and renamed as

A. miyazakiense in 1974 (

Yoshida and Arizono, 1976), due to the presence of articulating plates in the buccal capsule, the characteristic feature of the genus

Arthrostoma. Although hookworms of other genera, such as

Arthrocephalus or

Placoconus, have been reported to infect raccoons in several countries,

A. miyazakiense has never been reported in countries other than Japan.

One of the most adaptable species of wildlife, raccoon dogs (

Nyctereutes procyonoides) are found throughout Korea, Japan, and China, with a recent report on the presence of the animal in European countries, such as Finland and Germany. Unlike the raccoon (

Procyon lotor), which belongs to the family Procyonidae, the raccoon dog is a member of the family Canidae, despite the fact that it resembles a raccoon in its markings, lifestyle, and body structure. Its broad geographical distribution and omnivorous nature expose the animal to a broad spectrum of pathogens and parasites (

Woon, 1967). Consequently, numerous parasites of raccoon dogs have been identified elsewhere (

Sato et al., 1999b). Raccoon dogs are also known to be carriers of rabies, canine distemper, encephalitis, coccidiosis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, leptospirosis, roundworms, and mange mites.

Limited reports regarding the pathogenic organisms in raccoon dogs of Korea are available, in that infestations of ticks (

Lee et al., 1997) and mange mites have been previously documented, as have outbreaks of canine distemper and rabies (

So et al., 2002;

Kim et al, 2005). In this report, 10 raccoon dogs captured in Jeonnam Province, Korea were parasitologically evaluated, and we detected

A. miyazakiense in 2 raccoon dogs. Infective larvae of

A. miyazakiense were used to experimentally infect 3 puppies (3-mo-old), in order to characterize the infectivity of the parasite in dogs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Raccoon dogs examined

Ten raccoon dogs (4 males and 6 femalee, body weight 4.8 ± 0.6 kg) were captured between March 2002 and February 2005. They were collected by trapping from the suburban areas of Gwangju-shi (Gwangju Metropolitan City), Damyang-gun, and Hampyong-gun, Jeollanam-do, Korea. They were brought to the Animal Shelter at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Chonnam National University, and were housed either in dog cages or confined to a room. Upon arrival, the body weight of each animal was measured, and water, commercial dog food, and chicken meat were provided to the animals ad libitum.

Fecal examination and culture

Fecal samples from 5 raccoon dogs were parasitologically examined using a modified version of Sheather's sugar centrifugal flotation technique (

Sloss, 1994). Fecal samples that were infected with hookworms were mixed with granulated charcoal (Union Carbon Co., Ltd, Naju City, Korea) and cultured in glass jars in darkness at 25℃, in accordance with the methods described by Garcia and Ash (

1975). Daily observations of cultures for adequate moisture, and the identification of larvae were conducted with the aid of both compound and dissecting microscopes. Infective larvae present in the mixed cultures were recovered using a Baermann's apparatus (

Garcia and Ash, 1975).

The infective 2nd stage larvae from the charcoal cultures were orally administered to 3 puppies, 3-month-old, helminth-free, mixed-bred, at a dosage of 100 larvae per dog. After 12 days, the dogs reached patency with monospecific hookworm infections. Adult A. miyazakiense worms were collected from the feces of these dogs, following deworming with a commercial anthelmintic (Drontal Plus, Bayer Animal Health, Leverkusen, Germany).

Collection and identification of adult hookworms

One of the 2 raccoon dogs that discharged hookworm eggs in the feces died soon after it was brought to the Animal Shelter. Numerous adult hookworms were collected in the duodenum of necropsied animal. Some worms collected from a necropsied raccoon dog and some from experimental puppies were fixed with 10% formalin, and then prepared as specimens for microscopic observations. They were identified based on the morphologic characteristics described by Shimada (

1979) and Yoshida and Arizono (

1976).

The microculture slides used to observe the development of the larvae were prepared using a microscope slide glass (75 × 25 mm) on which a cover glass (22 × 40 mm) was mounted at a height of 0.8 mm, using a couple of polypropylene bars (0.8 × 1.0 × 22 mm) fixed with a silicone-based sealant (

Park et al., 2005). The microculture cell space between the slide glass and cover glass held approximately 700 µl of medium. Mature eggs of

A. miyazakiense harvested from the feces of infected animals were washed in water and pipetted into the cell space, after which each microculture slide was placed into a disposable petri dish (87 × 15 mm, Green Cross Medical, Inc., Seoul, Korea). Three layers of paper towel wet with deionized distilled water were positioned in the bottoms of the covered Petri dishes in order to provide humidity, and to minimize the evaporation of the culture medium. A couple of wood sticks were placed between the wet paper towel and the microculture slide. Petri dishes with microculture slides were maintained at room temperature (23-25℃). The culture slides were exposed to fluorescent lighting at 400 lux illumination for 12 hr everyday.

RESULTS

Results of fecal examination

Four species of helminth eggs and 1 species of protozoan cyst were detected by the fecal examination of 5 raccoon dogs. Two of the 5 raccoon dogs discharged the eggs of hookworms,

Toxocara sp. and

Trichuris sp. in their feces.

Capillaria sp. eggs and

Giardia sp. cysts were observed in the feces of 3 animals (

Table 1).

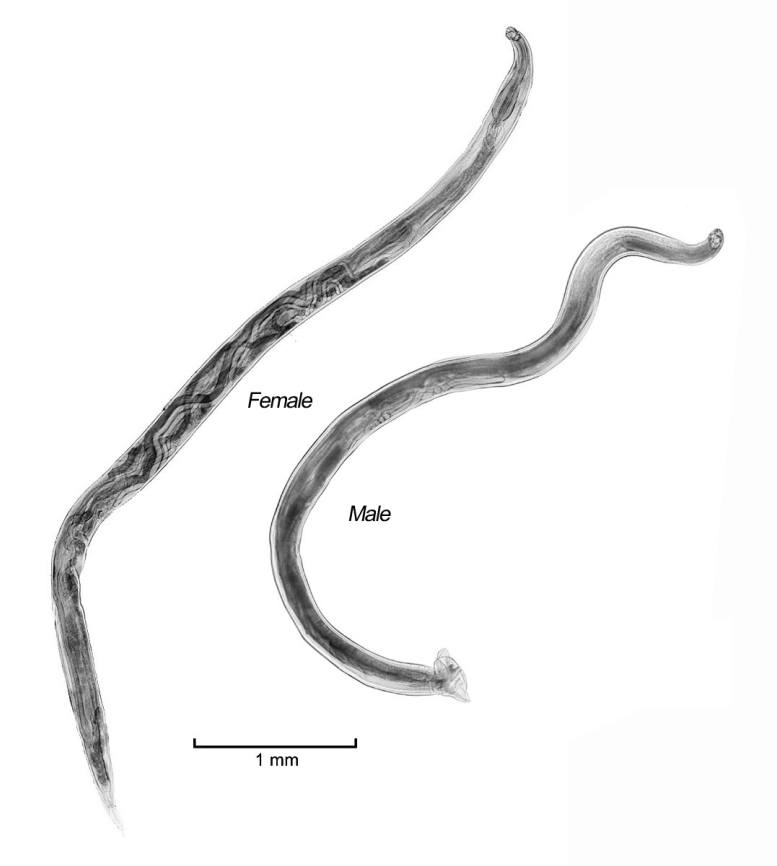

Adult hookworms collected from a necropsied raccoon dog and experimental puppies were whitish in color, rather small and slender, with cuticles striated finely in a transverse direction, and the lengths of the female and male worms were 6.0-8.0 mm and 4.7-5.9 mm, respectively (

Fig. 1;

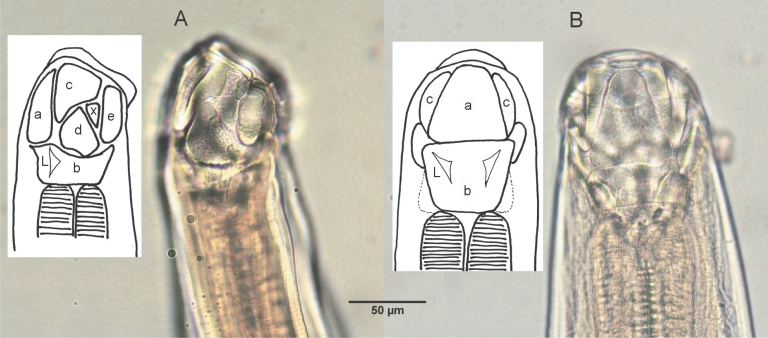

Table 2). The mouth part of adult worms had the following features: anterodorsal, buccal capsule composed of 10 articulated plates which included 1 basal, 1 ventral, 2 ventrolateral, 2 lateral, 2 dorsolateral, and 2 mediolateral plates (

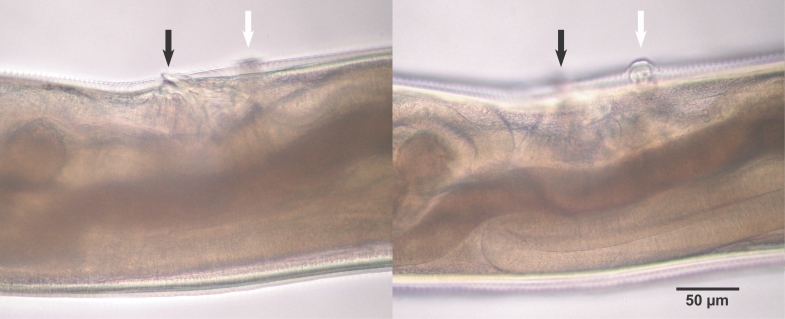

Fig. 2). The buccal capsule did not harbor cutting plates or teeth, but had a vertebra-shaped basal plate and a ventral pair of conspicuous lancets. Prevulval papillae were observed right-sidedly (

Fig. 3). Eggs were 60-65 × 35-40 µm (average, 62.5 × 35 µm) in size, and was indistinguishable morphologically with

Ancylostoma caninum (

Fig. 4).

Upon incubation of eggs at room temperature, eggs became embryonated within 30 hr and subsequently hatched within 48 hr (

Table 3). Only 54% of embryonated eggs were hatched by the 2

nd day of culture, when the eggs were incubated at 25℃. All eggs cultured at 30℃ hatched and became 1st stage larvae within 2 days (data not shown). The average length of the first-stage larvae at the time of hatching was 325 µm (range: 320-330 µm) and had a well-developed digestive system, mouth, oesophagus, and anus.

The 2

nd stage larvae were observed on the 3rd day of culture. The length of larvae was 505-695 µm (av. 638.1 ± 100.4 µm). When we infected to puppies on 14th day of culture, the range of the larval length was 620-720 µm (av. 650 µm) and was ensheathed (

Fig. 5). Upon incubation of eggs at room temperature, eggs became embryonated within 30 hr and subsequently hatched within 48 hr (

Table 3). The size of larvae grew above 600 µm within 6 days of culture to become an infective stage (

Table 4;

Fig. 5). Oral inoculation of 2-weeks old infective larvae from the charcoal culture into 3 helminth-free dogs resulted in patency at 12th day after infection, as evidenced by the presence of hookworm eggs in the feces.

DISCUSSION

Since Nagayosi (

1955) first identified

A. miyazakiense from the intestines of raccoon dogs captured in Japan, the parasite has been reported only in wild animals in Japan (

Sato et al., 1999a,

1999b,

2006). It appears that the parasite is particularly common in Aomori and Akita Prefectures, Japan, as 18 of 20 raccoon dogs caught in these areas were infected with the parasite. The parasite was also found in raccoon dogs in Miyazaki, Kyoto, and Hokkaido Prefectures (

Yoshida and Arizono, 1976). However, there have been no reports thus far of

A. miyazakiense infection in wild animals found in countries other than Japan. By the present study, it has been first confirmed that

A. miyazakiense is infected in raccoon dogs of the Republic of Korea.

Although

A. miyazakiense naturally parasitizes the small intestines of raccoon dogs, the parasite has also been found in a wild fox caught in Japan (

Sato et al., 1999b). Thus, it remains possible that the parasite may be found in other carnivores. Shimada (

1979) described the detailed life cycle of

A. miyazakiense in experimentally infected puppies. In this paper, we verified that dogs can be experimentally infected with

A. miyazakiense.

Besides

A. miyazakiense, 2 more species of hookworms,

Arthrocephalus lotoris and

Ancylostoma kusimaense, have been reported to naturally infect animals in the raccoon family worldwide. Raccoons (

P. lotor) distributed throughout North America commonly harbor

A. lotoris in their intestines. Being the most prevalent helminth species encountered in the intestines of raccoons in North America, the parasite has also been determined to infect black bears (

Crum et al., 1978). Originally dubbed

Uncinaria lotoris by Schwartz (

1925), the adult parasite of

A. lotoris has a buccal capsule surrounded by articulating plates, as is also observed in

Arthrostoma and

Placoconus (

Schmidt and Kuntz, 1968).

Arthrostoma has 8 or 10 articulating plates, whereas

Placoconus has 5. Although the adult worm of

A. lotoris evidences a dorsal cone in the buccal capsule, it does not possess ventral lancets. A high prevalence of

A. lotoris infection has been previously reported in north-central Arkansas (29/30, 97%,

Richardson et al., 1992) and western Kentucky (80%, 56/70,

Cole and Shoop, 1987). However,

Arthrocephalus has not yet been found in any other animals of Japan or Korea.

Raccoon dogs in Japan were reported to harbor another hookworm,

Ancylostoma kusimaense, or the badger hookworm (

Yoshida, 1965;

Yoshida et al., 1974). In a survey of 54 wild carnivores in the north-western part of the Tohoku region of Japan, 12 of 14 (86%) raccoon dogs (

N. procyonoides viverrinus) harbored

A. kusimaense in their small intestines (

Sato et al., 1999a). This hookworm, originally described by Nagayoshi (

1955), was collected from badgers in Japan. Although the raccoon dogs captured in this study did not harbor

A. kusimaense, the close proximity of Japan to the Korean peninsula shows that raccoon dogs in Korea may also harbor

A. kusimaense.

Herein, we described the isolation and identification of A. miyazakiense from raccoon dogs caught in Korea, and also report that the infective larvae were demonstrated to successfully parasitize puppies. To the best of the author's knowledge, this study constitutes the first record of A. miyazakiense reported in raccoon dogs living outside of Japan.

References

Fig. 1Adult female and male of A. miyazakiense.

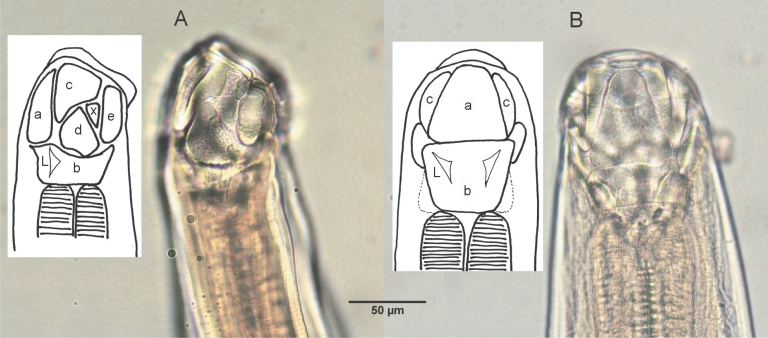

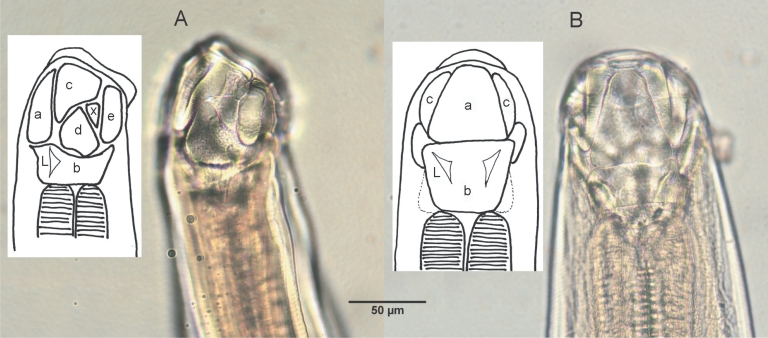

Fig. 2Lateral

(A) and dorsal

(B) views of the buccal capsule of adult

A. miyazakiense. Note that the buccal casule is composed of articulated plates (a, ventral plate; b, basal plate; c: ventrolateral plates; d, lateral plates; e, dorsalateral plates; x, mediolateral plates; L, lancets; illustration redrawn after Yoshida and Arizono,

1976).

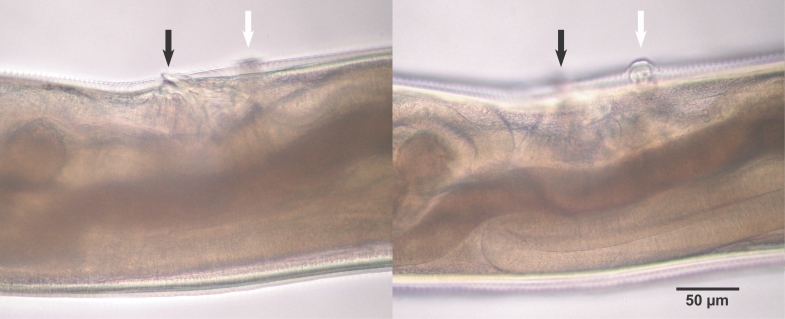

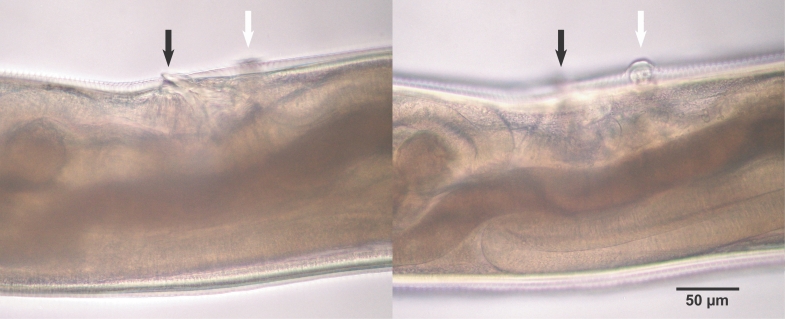

Fig. 3Characteristic single prevulval papillae of A. miyazakiense at 2 different focal depths. Note that the prevulval papillae is on the right side of the body. Black arrows: vulva, white arrows: vulval papillae.

Fig. 4An egg of Arthrostoma miyazakiense (60 × 40 µm).

Fig. 5The infective 2nd stage larva of A. miyazakiense, ensheathed.

Table 1.Results of fecal examination of 5 raccoon dogs captured in southwestern area of Korea

Table 1.

|

Dog ID no. |

Fecal egg counts

|

|

Toxocara sp. |

Trichuris sp. |

Arthrostoma miyazakiense

|

Capillaria sp. |

Giardia sp. |

|

1 |

560a)

|

10 |

15 |

58 |

+b)

|

|

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

- |

|

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

|

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

5 |

120 |

7 |

5 |

25 |

+ |

Table 2.Comparative measurements of the Korean isolates of

Arthrostoma miyazakiense (

Nagayosi, 1955) with Japanese isolates

Table 2.

|

Body parts measureda)

|

This study

|

Nagayosib)

|

Yoshidac)

|

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Body length |

4,700-5,900 |

6,000-8,000 |

4,000 |

7,000-9,000 |

4,900-5,700 |

6,400-8,200 |

|

Buccal capsule |

162-200 |

174-240 |

140-150 |

280-290 |

154-206 |

180-252 |

|

No. of plates |

10 |

10 |

- |

- |

10 |

10 |

|

- length |

- |

- |

- |

- |

68-84 |

84-88 |

|

- width |

- |

- |

- |

- |

52-66 |

60-76 |

|

Esophagus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- length |

460-520 |

500-580 |

- |

450-500 |

464-512 |

512-576 |

|

- width |

76-110 |

80-132 |

- |

100 |

84-108 |

76-128 |

|

Excretory pore from the anterior end |

320-380 |

380-430 |

- |

- |

336-368 |

368-416 |

|

Cervical papillae from anterior end |

- |

- |

- |

- |

360-408 |

392-448 |

|

Spicule length |

1,100-1,400 |

- |

1440 |

- |

1,400-1,230 |

- |

|

Gubernaculum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- length |

80-122 |

|

- |

|

92-110 |

|

|

- width |

10-20 |

|

|

- |

13-15 |

|

|

Vulva from posterior end |

- |

200-300 |

- |

230-300 |

- |

217-261 |

|

Tail length |

250-300 |

|

- |

|

176-240 |

|

|

No. and position of vulval papillae |

|

1 prevulval, right sided |

|

- |

|

1 prevulval, right sided |

|

Egg size |

|

62.5 x 35 |

|

|

|

64-76 x 32 |

Table 3.Development of Arthrostoma miyazakiense 2nd stage infective larvae

Table 3.

|

Time after culturea) (hr) |

No. of eggs or larvae (%)

|

|

Eggs |

Embryonated eggs |

2nd stage infective larvae |

|

24 |

10 (100) |

0 |

0 |

|

30 |

7 (30) |

16 (70) |

0 |

|

48 |

14 (41) |

2 (5) |

18 (54) |

|

72 |

10 (48) |

1 (4) |

10 (48) |

Table 4.Development of Arthrostoma miyazakiense larvae after culture

Table 4.

|

Days after culturea)

|

Larval length (μm, mean ± SD) |

No. of larvae measured

|

|

< 400 |

400-600 |

> 600 |

Total |

|

2 |

325.0 ± 8.5 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

3 |

549.2 ± 15.9 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

4 |

549.2 ± 100.3 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

12 |

|

6 |

600.0 ± 74.7 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

10 |

|

8 |

655.3 ± 22.6 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

15 |

|

10 |

658.3 ± 21.5 |

0 |

0 |

20 |

20 |

|

12 |

646.2 ± 16.1 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

13 |

|

14 |

672.1 ± 15.9 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

14 |

|

16 |

650.5 ± 20.6 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

10 |

|

18 |

673.3 ± 17.4 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

11 |

|

20 |

661.5 ± 22.0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

10 |