Abstract

A total of 44 adult or juvenile nutrias were necropsied for disease survey. A large nodule was found in the liver of a nutria. The histopathological specimen of the hepatic nodule was microscopically examined, and sectional worms were found in the bile duct. The worms showed a tegument with spines, highly branches of vitelline glands and intestine. Finally, we histopathologically confirmed fascioliasis in a wild nutria. In the present study, a case of fascioliasis in a wild nutria is first confirmed in Korea.

-

Key words: Myocastor coypus, Fascioliasis, nutria, liver fluke

INTRODUCTION

Myocastor coypus, also known as nutria or river rat, a native of South America, has been introduced into several countries in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia including Korea for fur farming and meat production. In Korea, however, nutrias were negligently released into the wild due to the lack of marketa-bility and inadequate management in the farms. The nutrias rapidly bred in wetlands near Nakdong-gang (gang means river), Korea and became serious pests damaging crops and wetland plants.

As a rodent, nutria is susceptible to many diseases including rabies, equine encephalomyelitis, paratyphoid, salmonellosis, papillomatosis, leptospirosis and toxoplasmosis, rickettsiosis, coccidiosis, and sarcosporidiosis [

1]. Nutria inhabits both terrestrial and aquatic areas and is the reservoir host for various species of parasites. It is frequently exposed to parasites, with life cycles in both habitats. They are well known hosts of parasites such as

Toxoplasma gondii [

2],

Capillaria hepatica [

1,

3],

Giardia spp. [

3], Coccidia [

2,

3],

Echinococcus multilocularis [

4], and

Strongyloide myopotami [

5]. Infections with

Fasciola hepatica in nutrias were reported in France and Argentina with relatively high prevalences, 21.6% and 11.1%, respectively [

3,

6]. However, there were no reports of nutria fascioliasis in Asian Continent. Therefore, we report the first fascioliasis case of nutria in Korea.

CASE RECORD

According to the eradication campaign of The Korean Ministry of Environment, nutrias were captured in wetlands around Nakdong-gang. Among them, a total of 44 adult or juvenile nutrias were brought to our laboratory for disease survey. They were 20 males and 24 females, and their body weight ranges varied from 1.7 to 7.5 kg. The nutrias were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation for necropsy and disease screening. Necropsy results showed hepatic milky spots occurring as microgranulomas in 19 nutrias.

C. hepatica eggs and worms were detected in 5 of these nutrias which we reported in a previous study [

1]. Unlike the hepatic milky spots induced by

C. hepatica, one nutria had a large nodular lesion in the liver. Histopathology of the liver tissue was conducted by processing the samples routinely and embedded in paraffin wax. They were cut into 4-μm-thick sections, which were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined microscopically.

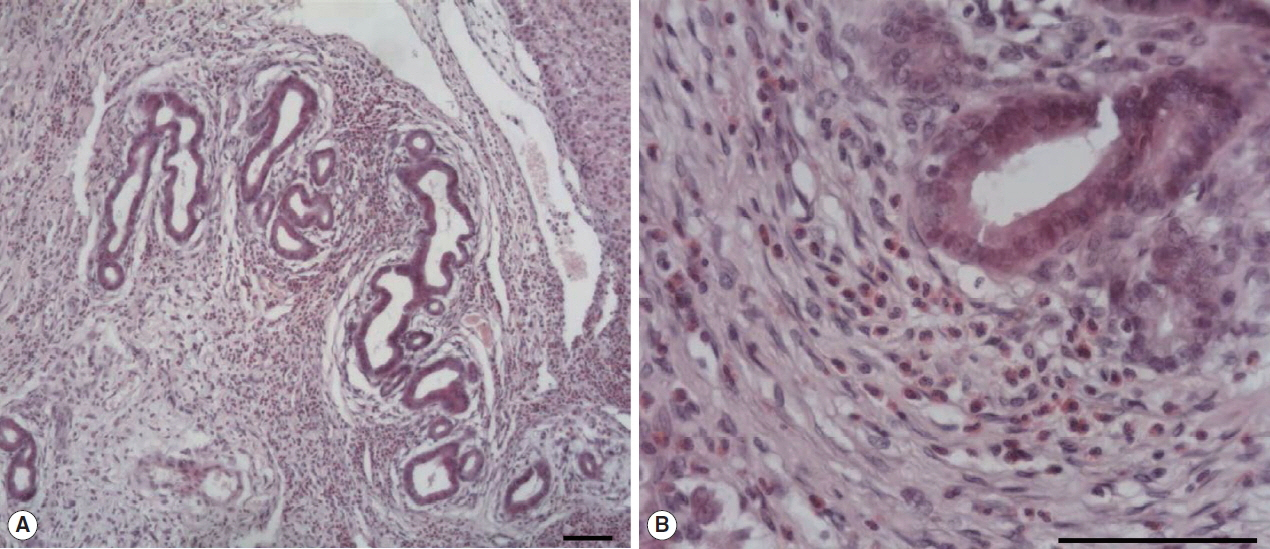

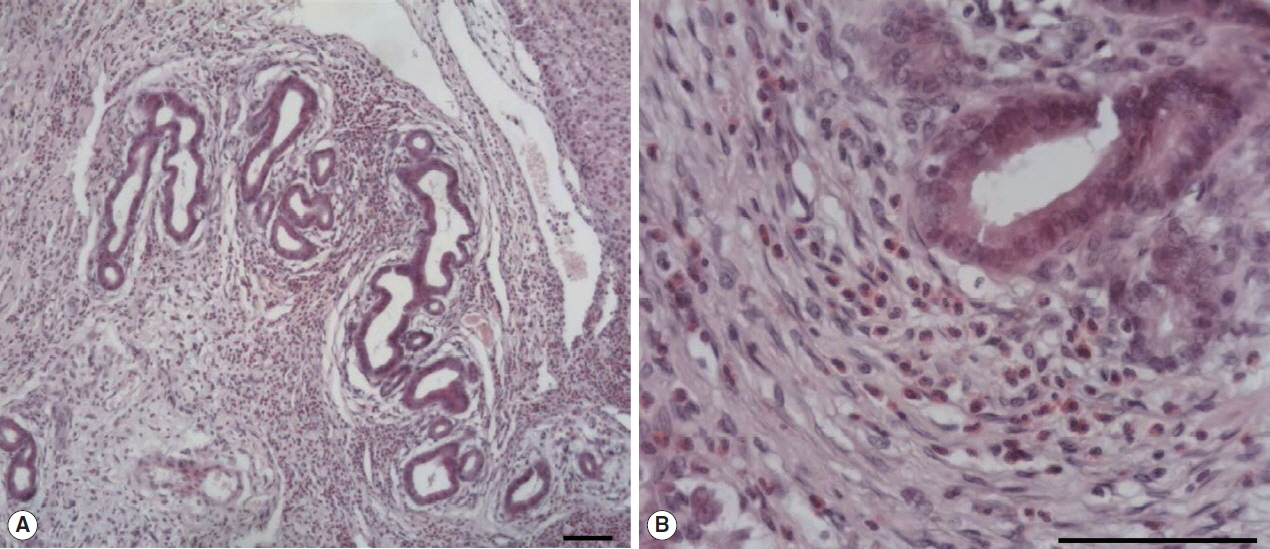

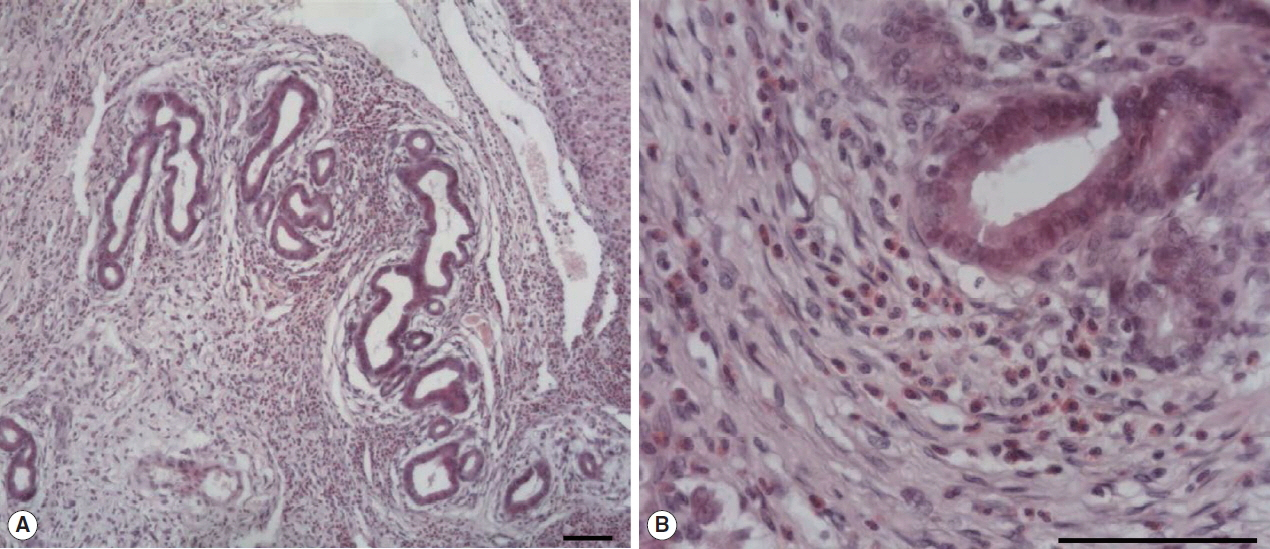

The large hepatic nodular lesion was grossly hemorrhagic and represented a necrotic granuloma. Microscopically, the lesion showed large and extensive hemorrhagic necrosis and occasionally contained calcification with mineral deposits. The bile duct epithelial cells were hyperplastic with infiltration of numerous inflammatory cells including epithelioid cells and eosinophils (

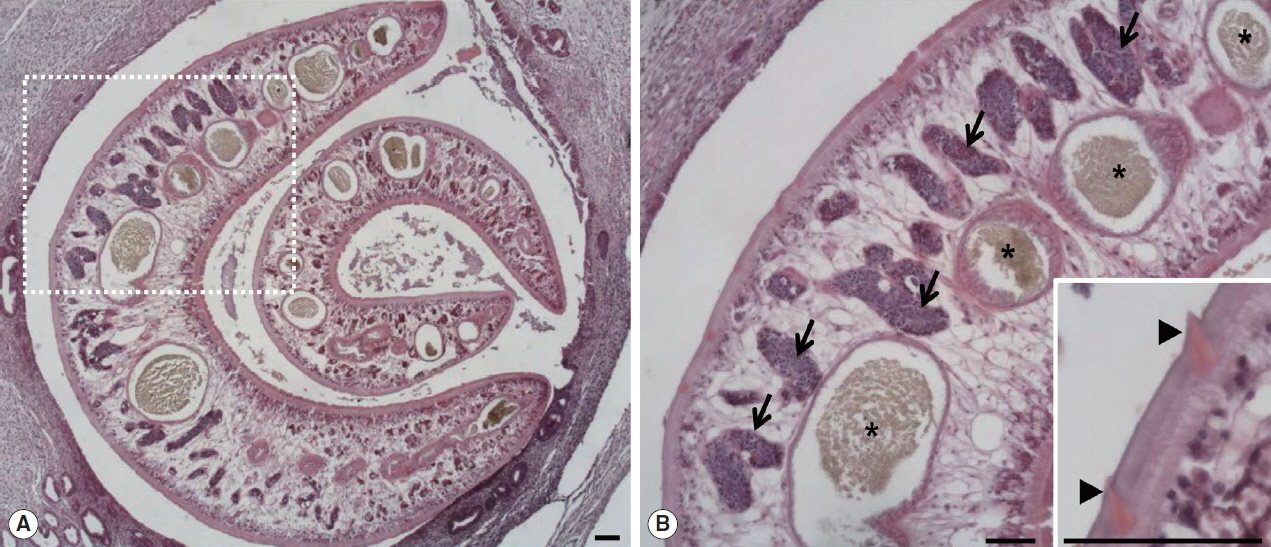

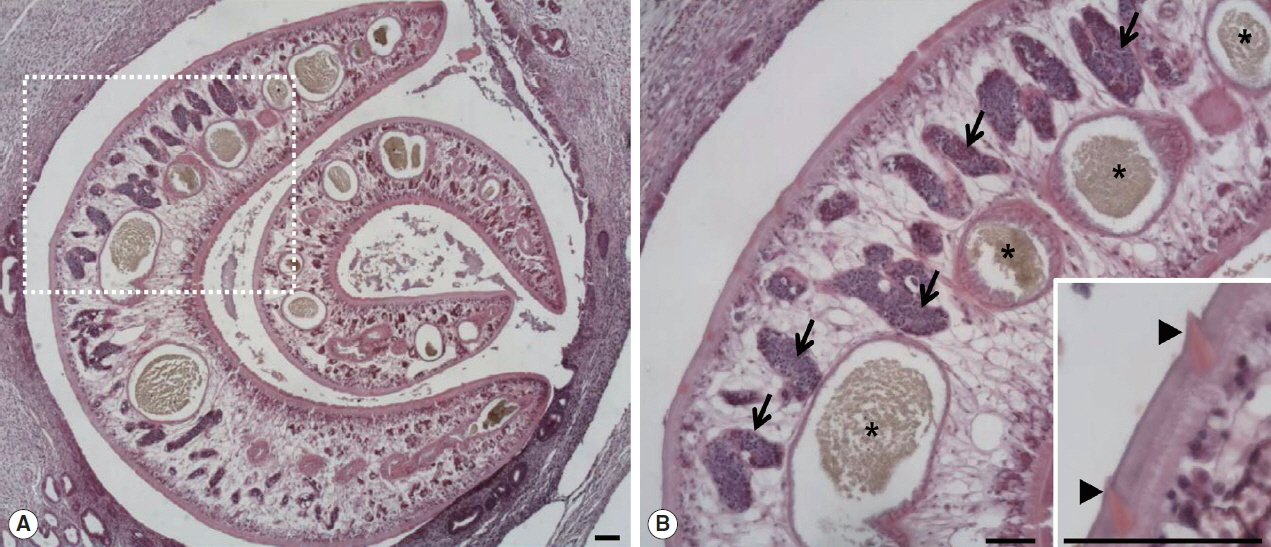

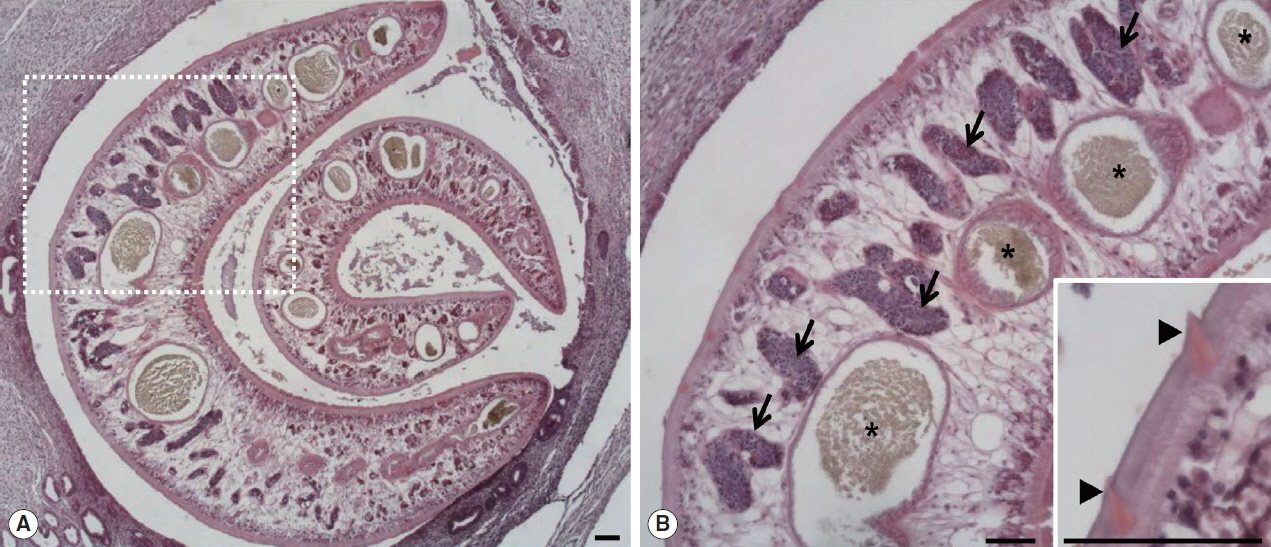

Fig. 1A, B). Parasitic worms were found in the lesion (

Fig. 2A). The worms had numerous tegumental spines on the outer layer followed by a thin basement membrane and underlying muscle layers. Highly branched vitelline glands were distributed along both lateral sides of the worm. The vitelline glands and multiple intestinal lumen were embedded in the mesenchyma having loosely arranged nucleated cells with syncytial network of fibres below the muscle (

Fig. 2B). No eggs were found in the biliary lesion and worms. By the microscopic findings, we concluded that the nutria was infected with

Fasciola sp. as the worms were parasitic in the bile duct, exhibited tegumental spines, and had highly branches of vitelline glands and intestine.

DISCUSSION

For a differential diagnosis, the microscopic features of

Fasciola sp. should be compared with other types of liver flukes with similar egg size, shape and adult worm morphology.

Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, and

O. felineus belong to the family Opisthorchiidae are major liver flukes with

Fasciola spp. which are medically important in humans.

Fasciola spp. show a worldwide distribution.

C. sinensis is endemic in Asia including Korea while

O. viverrini and

O. felineus mainly distribute in Southeast Asia and Central and Western Eurasia, respectively [

7]. Those liver flukes exhibit life cycles involving freshwater snails as an intermediate host and main definitive hosts are human, however, dogs, cats and rats serve as the final hosts [

8]. Adult opisthorchiid flukes are morphologically very similar and differ primarily in shape and position of testes, and the arrangement of vitelline glands [

9].

F. hepatica differs from adult opisthorchiid flukes mainly by the presence of tegumental spines, highly branched vitelline glands and intestine [

9–

12]. The tegumental syncytium of

F. hepatica is made of a homogeneous layer of scleroprotein, which covers the fluke and protects it from digestive enzyme of the host. It bears tegmental spines which anchor the fluke to the bile duct of the host and facilitate motion [

10]. Juvenile opisthorchiid flukes have spines in the tegument, but completely lose them in the adults [

9]. Adult

F. hepatica is different from opisthorchiid flukes by the location of uterus. In

F. hepatica, the uterus is small and located in an anterior part of the body, and therefore, the eggs within the uterus are very unlikely to be detected in the cross-sections of the worm [

13]. However, the uterus of opisthorchiid flukes lies long in the middle of the body increasing the probability of finding intrauterine eggs in the cross-sections [

9]. In this case, the eggs and uterine structures were not found. Generally, it is hard to confirm species name without finding of parasitic eggs because of similar histopathological features of

Fasciola spp. However,

F. hepatica is wellknown as the most prevalent species among

Fasciola spp. in Korea, and histopathological characteristics of the worm, such as tegumental spines, highly branched vitelline glands and intestine, are distinguished from opisthorchiid flukes. Therefore, we concluded a case of

F. hepatica infection in the nutria. Snails (family Lymnaeidae) are the intermediate hosts of

F. hepatica, which has a range of definitive hosts in various mammals. Distribution of these hosts is worldwide including Europe, America, and Asia [

14]. In Korea, the prevalence of

F. hepatica infection was high in cattle before 2000 [

15]. The infestations are still reported as PCR diagnosis of

F. hepatica DNA from the intermediate host snails [

16,

17]. However,

F. hepatica infection in wild animals is rarely identified. The diagnosis of

F. hepatica infection in animals and humans has been confirmed by direct visual observations of the adult worms and trematode eggs or by PCR analysis [

15,

18]. The morphological characteristics of

F. hepatica worm and egg are very well-known. However, the histopathological features of the worm have been poorly reported. It is important to know the histopathological characteristics of the parasites because a small number of the infection in the host can be found occasionally in the inflammatory lesions or ectopic sites without direct visual observations of the worm or eggs. In conclusion, this case represents the first reported incidence of

F. hepatica infection occurring in wild nutria and elucidates the comprehensive histopathological features of the parasite.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no competing financial interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work (RPP-2015-000) was supported by the fund of Research promotion program, Gyeongsang National University, 2015.

Fig. 1Microscopic examination of hepatic granuloma infected with Fasciola sp. in the wild nutria. (A) Hyperplasia of bile duct epithelial cells with infiltration of numerous inflammatory cells. (B) Infiltration of eosinophils and epithelioid cells with bile duct hyperplasia. H&E. Scale bar=100 μm.

Fig. 2Two worms of

Fasciola sp. in the bile duct of the wild nutria. (A) Bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis around the worms are noted. (B) Magnified view of the dotted square area in

Fig. 1A. Pointed tegmental spines (arrowheads, inset), highly branches of vitelline glands (arrows) and intestinal lumens (*) embedded in mesenchyma are characteristically seen in a sectioned worm. H&E. Scale bar=100 μm.

References

- 1. Hong IH, Kang SY, Kim JH, Seok SH, Lee SK, Hong SJ, Lee SY, Park SJ, Kong JY, Yeon SC. Histopathological findings in wild Nutrias (Myocastor coypus) with Capillaria hepatica infection. J Vet Med Sci 2016;78:1887-1891.

- 2. Bollo E, Pregel P, Gennero S, Pizzoni E, Rosati S, Nebbia P, Biolatti B. Health status of a population of nutria (Myocastor coypus) living in a protected area in Italy. Res Vet Sci 2003;75:21-25.

- 3. Martino PE, Radman N, Parrado E, Bautista E, Cisterna C, Silvestrini MP, Corba S. Note on the occurrence of parasites of the wild nutria (Myocastor coypus, Molina, 1782). Helminthologia 2012;49:164-168.

- 4. Umhang G, Lahoreau J, Nicolier A, Boué F.

Echinococcus multilocularis infection of a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) and a nutria (Myocastor coypus) in a French zoo. Parasitol Int 2013;62:561-563.

- 5. Choe S, Lee D, Park H, Oh M, Jeon HK, Eom KS.

Strongyloides myopotami (Secernentea: Strongyloididae) from the intestine of feral nutrias (Myocastor coypus) in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2014;52:531-535.

- 6. Ménard A, Agoulon A, L’Hostis ML, Rondelaud D, Collard S, Chauvin A.

Myocastor coypus as a reservoir host of Fasciola hepatica in France. Vet Res 2001;32:499-508.

- 7. Fürst T, Duthaler U, Sripa B, Utzinger J, Keiser J. Trematode infections: liver and lung flukes. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012;26:399-419.

- 8. Chai JY, Darwin Murrell K, Lymbery AJ. Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: status and issues. Int J Parasitol 2005;35:1233-1254.

- 9. Kaewkes S. Taxonomy and biology of liver flukes. Acta Trop 2003;88:177-186.

- 10. Ravidà A, Cwiklinski K, Aldridge AM, Clarke P, Thompson R, Gerlach JQ, Kilcoyne M, Hokke CH, Dalton JP, O’Neill SM.

Fasciola hepatica surface tegument: glycoproteins at the interface of parasite and host. Mol Cell Proteomics 2016;15:3139-3153.

- 11. Lim JH. Liver flukes: the malady neglected. Korean J Radiol 2011;12:269-279.

- 12. Lvova MN, Tangkawattana S, Balthaisong S, Katokhin AV, Mordvinov VA, Sripa B. Comparative histopathology of Opisthorchis felineus and Opisthorchis viverrini in a hamster model: an implication of high pathogenicity of the European liver fluke. Parasitol Int 2012;61:167-172.

- 13. Hanna R.

Fasciola hepatica: histology of the reproductive organs and differential effects of triclabendazole on drug-sensitive and drug-resistant fluke isolates and on flukes from selected field cases. Pathogens 2015;4:431-456.

- 14. Waitkinsa SA, Wanyangu S, Palmer M. The coypu as a rodent reservoir of leptospira infection in Great Britain. J Hyg (Lond) 1985;95:409-417.

- 15. Sohn BW, Kang GS, Han TH. Studies on the optimal time for therapy of Fasciola spp. infected cattle in central area of Korea. Korean J Vet Serv 1992;15:1-6.

- 16. Kim HY, Choi IW, Kim YR, Quan JH, Ismail HA, Cha GH, Hong SJ, Lee YH.

Fasciola hepatica in snails collected from water-dropwort fields using PCR. Korean J Parasitol 2014;52:645-652.

- 17. Lee JH, Quan JH, Choi IW, Park GM, Cha GH, Kim HJ, Yuk JM, Lee YH.

Fasciola hepatica: infection status of freshwater snails collected from Gangwon-do (Province), Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2017;55:95-98.

- 18. Kang BK, Jung BK, Lee YS, Hwang IK, Lim H, Cho J, Hwang JH, Chai JY. A case of Fasciola hepatica infection mimicking cholangiocarcinoma and ITS-1 sequencing of the worm. Korean J Parasitol 2014;52:193-196.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- The use of Glutathione-S-transferase levels as marker of hepatic damage in chronic fasciolosis in cattle

Al-Hassan Mohammed Mostafa, Gehan Mohammed Sayed, Ali Ali Hassan Al-Ezzi, Alaa Eldin Kamal

Veterinary Parasitology.2025; 339: 110577. CrossRef - Fasciola hepatica infection in Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus)

Na-Hyeon Kim, Min-Gyeong Seo, Bumseok Kim, Yu Jeong Jeon, In Jung Jung, Il-Hwa Hong

Parasites, Hosts and Diseases.2025; 63(3): 243. CrossRef - Intestinal parasites of Myocastor coypus (Rodentia, Myocastoridae) on animal farms in Eastern Ukraine

N. V. Sumakova, A. P. Paliy, O. V. Pavlichenko, R. V. Petrov, B. S. Morozov, V. M. Plys, A. B. Mushynskyi

Regulatory Mechanisms in Biosystems.2025; 16(3): e25117. CrossRef - Prevalence and hepatic histopathological findings of fascioliasis in sheep slaughtered in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Safinaz J. Ashoor, Majed H. Wakid

Scientific Reports.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Climate change induced habitat expansion of nutria (Myocastor coypus) in South Korea

Pradeep Adhikari, Baek-Jun Kim, Sun-Hee Hong, Do-Hun Lee

Scientific Reports.2022;[Epub] CrossRef -

Genetic diversity and relationships of the liver fluke

Fasciola hepatica

(Trematoda) with native and introduced definitive and intermediate hosts

Antonio A. Vázquez, Emeline Sabourin, Pilar Alda, Clémentine Leroy, Carole Leray, Eric Carron, Stephen Mulero, Céline Caty, Sarah Hasfia, Michel Boisseau, Lucas Saugné, Olivier Pineau, Thomas Blanchon, Annia Alba, Dominique Faugère, Marion Vittecoq, Sylvi

Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.2021; 68(4): 2274. CrossRef - Preputial gland adenoma in a wild nutria (Myocastor coypus): a case report

Joo-Yeon Kong, Hyo-Seok Kim, Seong-Chan Yeon, Jin-Kyu Park, Kyu-Shik Jeong, Il-Hwa Hong

Journal of Veterinary Science.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Preputial gland adenoma in a wild nutria (Myocastor coypus): a case report

Joo-Yeon Kong, Hyo-Seok Kim, Seong-Chan Yeon, Jin-Kyu Park, Kyu-Shik Jeong, Il-Hwa Hong

Journal of Veterinary Science.2019;[Epub] CrossRef