Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous protozoan parasite responsible for causing toxoplasmosis. Preventive measures for toxoplasmosis are currently lacking and as such, development of novel vaccines are of urgent need. In this study, we generated 2 virus-like particles (VLPs) vaccines expressing T. gondii rhoptry protein 4 (ROP4) or rhoptry protein 18 (ROP18) using influenza matrix protein (M1) as a core protein. Mice were intranasally immunized with VLPs vaccines and after the last immunization, mice were challenged with ME49 cysts. Protective efficacy was assessed and compared by determining serum antibody responses, body weight changes and the reduction of cyst counts in the brain. ROP18 VLPs-immunized mice induced greater levels of IgG and IgA antibody responses than those immunized with ROP4 VLPs. ROP18 VLPs immunization significantly reduced body weight loss and the number of brain cysts in mice compared to ROP4 VLPs post-challenge. These results indicate that T. gondii ROP18 VLPs elicited better protective efficacy than ROP4 VLPs, providing important insight into vaccine design strategy.

-

Key words: Toxoplasma gondii, virus-like particle, vaccine, rhoptry protein 4, rhoptry protein 18

INTRODUCTION

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular parasite that is distributed worldwide.

T. gondii is a common infectious organism that infects various types of mammals, including humans. Once infected,

T. gondii can spread to virtually all organs of the host such as the brain, eye, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, and cause toxoplasmosis [

1–

3]. Most healthy individuals are either asymptomatic or display minor symptoms upon

T. gondii infection. Toxoplasmosis causes inflammation, developmental delay, developmental disability, mental retardation, and induces stillbirth in severe cases. Additionally, congenital transmission of the parasite to the fetus can occur in AIDS patients or individuals receiving high-dose immunosuppressive therapy upon

T. gondii infection [

4].

Up to present, there is no vaccine to prevent toxoplasmosis in humans. Therefore, vaccine development studies of

T. gondii, specifically for immunodeficiency patients and pregnant women are necessary. A number of vaccine studies against toxoplasmosis using attenuated, inactivated, and genetically engineered vaccines have been reported. However, poor immunological efficacy were obtained [

5]. DNA vaccines incorporating rhoptry protein 4 (ROP4) and rhoptry protein 18 (ROP18) have been reported to be potential vaccine candidates against toxoplasmosis [

6,

7]. As with previously aforementioned studies, poor vaccine immunogenicity and effectiveness have been observed. For these reasons, development of novel vaccine formulation using novel technology would have a significant impact.

Innovative vaccine strategies, such as the application of virus-like particles (VLPs), have been widely used, particularly those consisting of influenza M1 proteins as the core protein of VLP and various antigens of pathogenic origin as surface proteins [

7]. We have reported VLP vaccines containing

T. gondii IMC or MIC8 proteins [

8,

9]. These VLP vaccines successfully inhibited

T. gondii replications and provided complete protection. ROP4 protein vaccine has been reported to significantly reduce brain cysts number upon

T. gondii DX strain challenge infection [

19]. ROP18 DNA vaccine significantly increases survival time compared with control mice upon intra-peritoneal challenge with RH strain [

6]. ROP18 VLP vaccination has been reported to reduce cyst counts and size significantly in the brain upon

T. gondii ME49 challenge infection [

10]. However, detailed reports of IgG isotypes, IgM and IgA antibody responses in sera against

T. gondii parasite antigens are currently lacking. For

T. gondii ROP4, although we have generated VLPs containing ROP4 together with influenza M1, its protective effect upon

T. gondii challenge infection remains to be investigated [

11]. More importantly, no comparison study of protective efficacy between ROP4 and ROP18 for any vaccine formulation has been reported. Therefore, a detailed comparison study assessing the antibody responses, immunogenicity and protective effects between

T. gondii ROP4 VLP and

T. gondii ROP18 VLP should contribute significantly to potential

T. gondii vaccine development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, parasites, cells and antibodies

Seven-week-old female BLAB/c mice were obtained from KOATECH (Pyeongtaek, Korea).

Toxoplasma gondii RH and ME49 strains were maintained according to the methods described previously [

12,

13]. All of the experimental procedures involving animals have been approved and conducted under the guidelines set out by Kyung Hee University IACUC.

T. gondii RH stain was used for RNA extraction, and

T. gondii ME49 was used for mice infection as well as serum collection on a regular basis [

9].

Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells were used for production of recombinant baculovirus (rBV) and virus-like particles were maintained in serum-free SF900 II medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) in spinner flasks at 140 rpm, 27°C. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b were purchased from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, Alabama, USA).

T. gondii RH tachyzoites were harvested from the peritoneal cavity of mice 4 or 5 days after infection by injecting 3 ml of 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) as described [

14]. Peritoneal exudate was centrifuged at 100 g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The parasites in the supernatant were precipitated by centrifugation at 600 g for 10 min, which were washed in PBS and sonicated.

Generation of T. gondii VLPs

Cloning of

T. gondii rhoptry protein 4 (ROP4),

T. gondii rhoptry protein 18 (ROP18) and influenza M1 were conducted as previously described [

10,

11]. Baculoviruses expressing ROP4, ROP18 and M1, and VLPs containing ROP4 or ROP18 together with influenza M1 were prepared as previously described [

10,

11].

Western blot was used to confirm characterization of the VLPs. The presence of ROP4 and ROP18 proteins were detected by western blot using mouse polyclonal antibody, which was collected from mice infected with

T. gondii ME49 strain 4 weeks post-infection. M1 protein expression in the VLPs were confirmed using monoclonal mouse anti-M1 antibody [

15].

Female, 7-week-old BALB/c mice (KOATECH, Pyeongtaek, Korea) were used. Groups of mice (n=6 per group) were intranasally immunized 3 times with 75 μg total VLPs protein at 4-week intervals. Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital plexus puncture before immunization. Naïve or vaccinated mice were challenged with 1,500 cysts of T. gondii ME49 in 100 μl PBS through the oral route. Mice were observed for 3 days to record body weight changes. Naïve mice challenge infected with ME49 cysts are henceforth annotated as Naïve+Cha.

Antibody responses in sera

The retro-orbital plexus puncture method was used to obtain blood samples from mice at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after prime, boost and second boost. Collected sera were stored at −20°C for antibody response evaluation. To measure T. gondii-specific antibodies, flat bottom 96-well immunoplates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of T. gondii antigen at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml in 0.05 M, pH 9.6 carbonate bicarbonate buffer per well. Afterwards, 100 μl of serum samples (diluted 1:50, 1:150, 1:450 in PBST) were added to respective wells and plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA, IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b diluted in PBST (100 μl/well) were added for secondary antibody.

ME49 cyst count in the brain

One month after infection, the brains of mice were collected, and 200 μl PBS was added into it, and it was finely ground with a syringe plunger. Approximately 5 μl of ground brain tissue was placed on a glass slide and observed under microscope to count the number of cysts. All samples were counted thrice to reduce counting errors.

Cellular immune response analysis

Spleens of mice were harvested 4 weeks post-challenge to determine cytokine responses to challenge infection. Single cell suspension of splenocytes were prepared and cells were count under microscope using hemocytometer. 1×106 cells/well were prepared in RPMI-1640 culture media supplemented with 10% FBS to culture splenocytes in 96-well culture plates in vitro. Then, cytokines IFN-γ, IL-6 and IL-10 levels were determined by BD OptEIA Set (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) using the culture supernatants harvested after 5 days. Cytokine concentration was quantified by ELISA (λ=450 nm, n=3) with reference to standard curves constructed with IFN-γ, IL-6 and IL-10 standard stock solutions.

Statistical analysis

All parameters were recorded for individuals within all groups. Data were compared using analysis of variance and the nonparametric one-way Kruskal–Wallis test in the PC-SAS system (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A P-value< 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

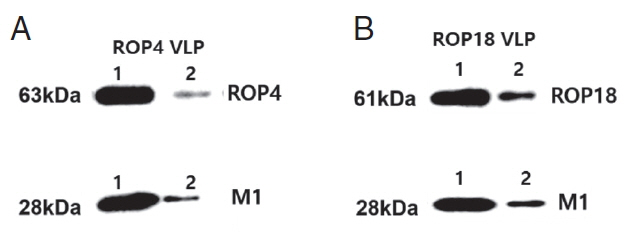

Generation of virus-like particles (VLPs)

Recombinant constructs in pFastBac vectors containing

T. gondii ROP4, ROP18 or influenza M1 were generated as described previously [

10,

11]. VLPs expressing

T. gondii ROP4 or ROP18 together with influenza M1 were produced following a procedure described previously [

11]. As seen in

Fig. 1, that both

T. gondii ROP4 (

Fig. 1A), ROP18 (

Fig. 1B) and influenza M1 (

Fig. 1) have been incorporated into the VLPs by western blot analysis with anti-

T. gondii polyclonal antibody and anti-M1 monoclonal antibody.

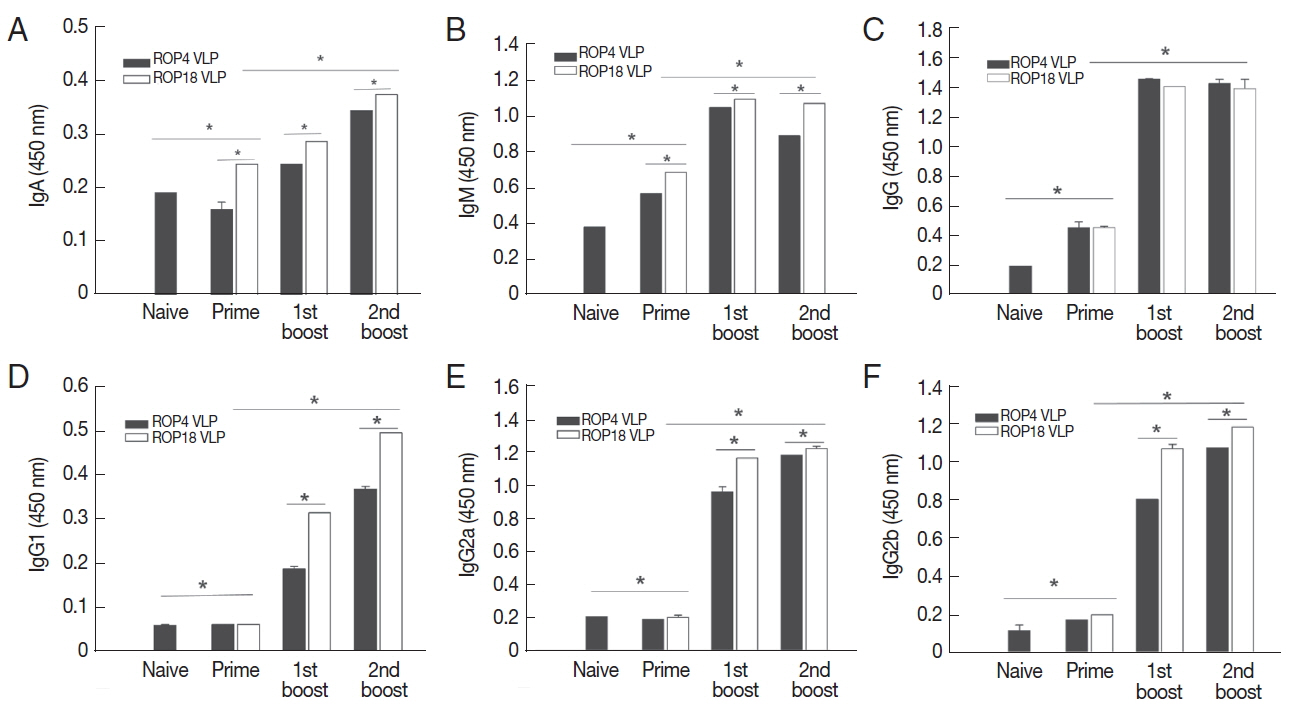

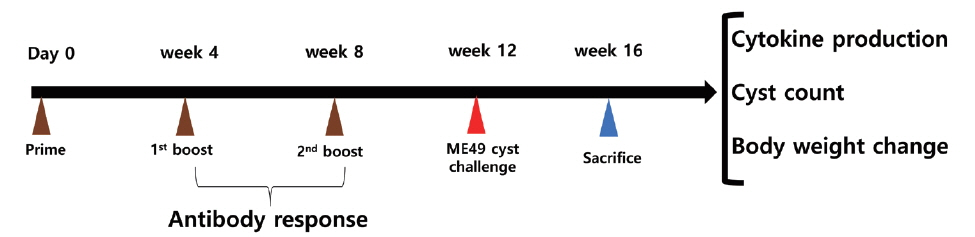

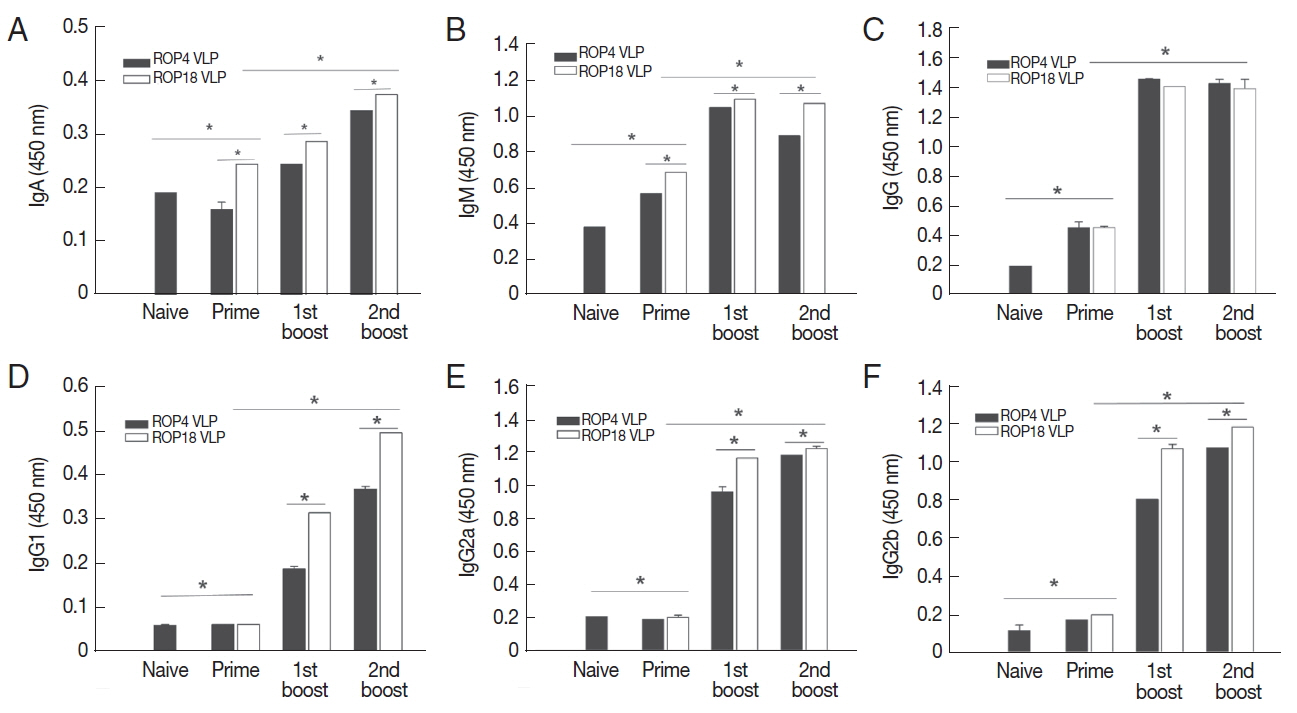

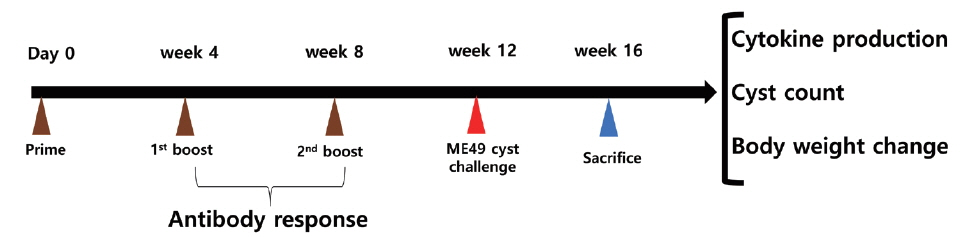

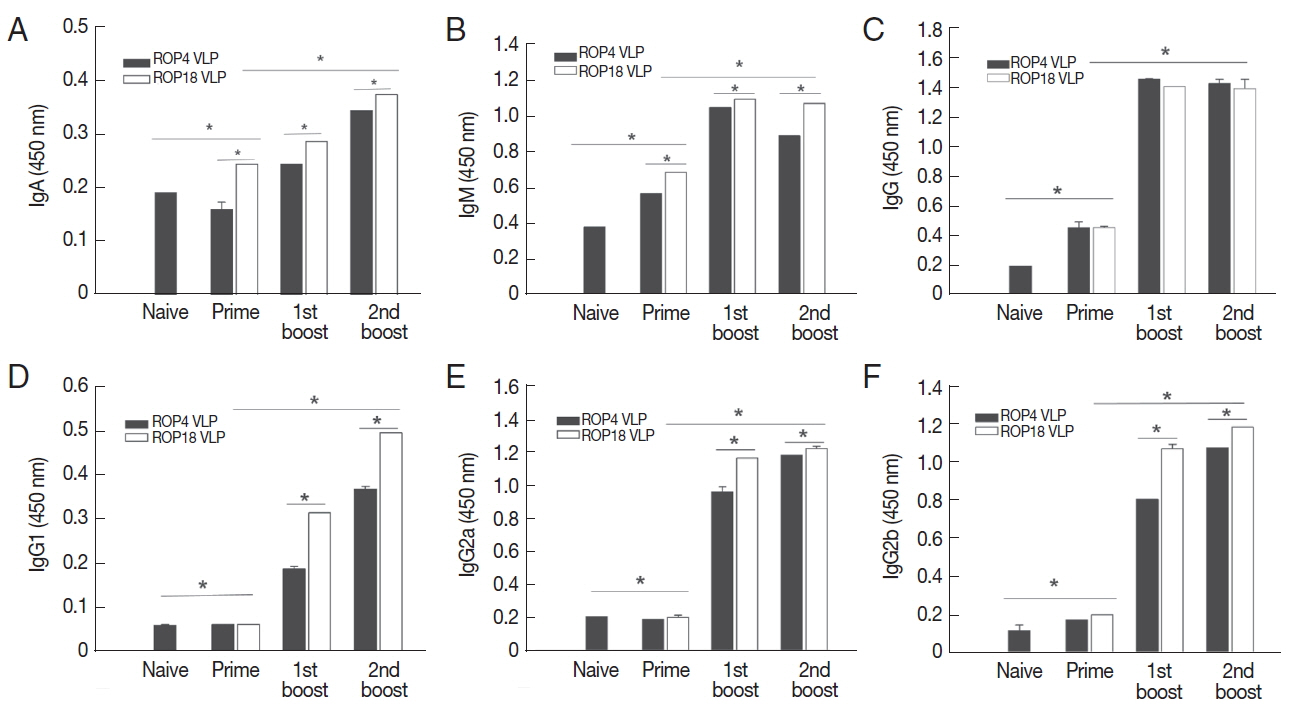

The levels of

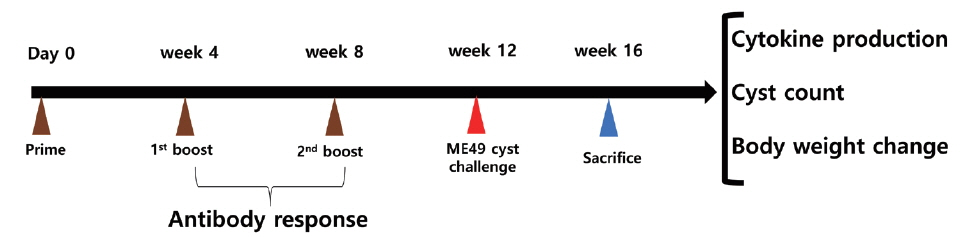

T. gondii-specific IgA, IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody responses after priming, boosting and second boosting were determined as outlined in the experimental schedule (

Fig. 2). As shown in

Fig. 3, ROP18 VLPs immunized group showed higher levels of

T. gondii-specific IgA (

Fig. 3A), IgM (

Fig. 3B), IgG (

Fig. 3C), IgG1 (

Fig. 3D), IgG2a (

Fig. 3E), and IgG2b (

Fig. 3F) antibody response compared to ROP4 VLPs (*

P <0.05).

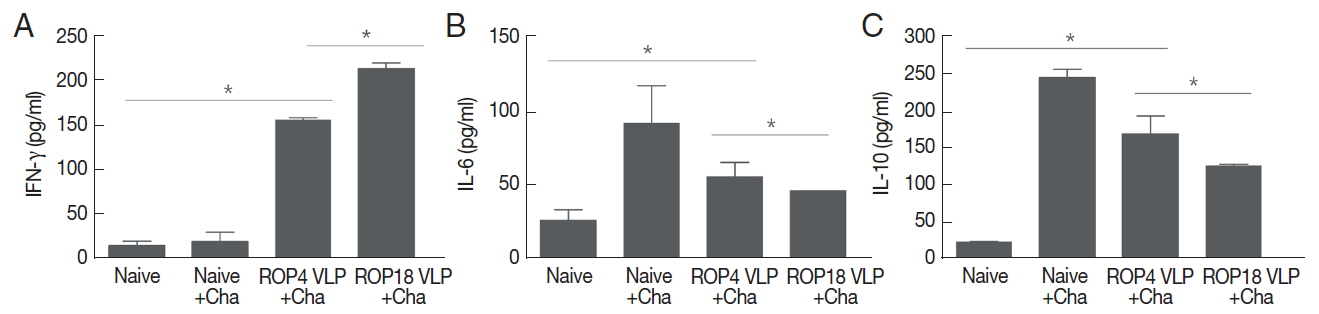

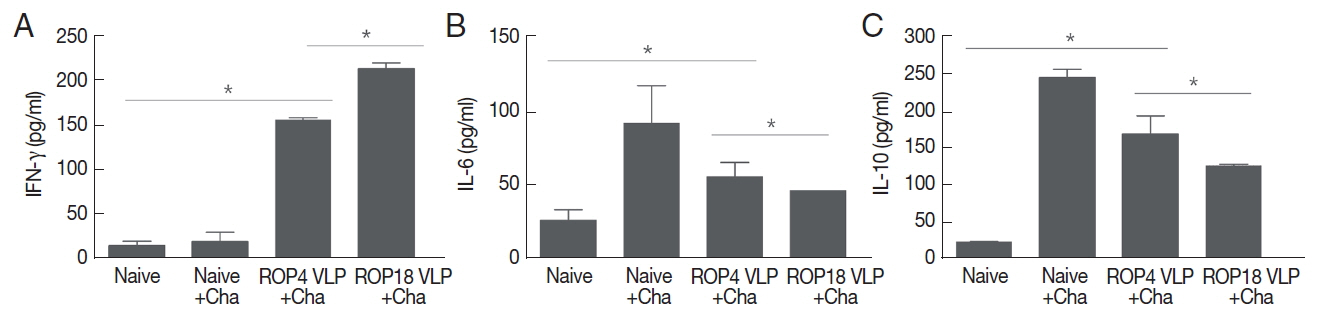

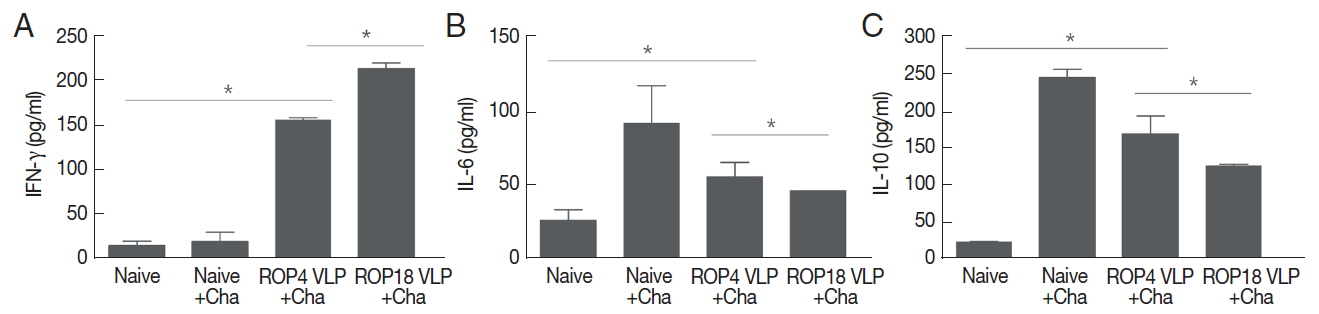

Splenocytes were cultured

in vitro to determine Th1-like cytokines IFN-γ and Th2-like cytokines IL-6 and IL-10 produced. As shown in

Fig. 4, higher level of IFN-γ was produced in both ROP4 VLP and ROP18 VLP vaccinations compared to Naïve or Naïve+Cha controls, with ROP18 VLP showing greater IFN-γ production compared to ROP4 VLP (

Fig. 4A; *

P <0.05). Naïve+Cha is that naïve mice that has been challenged with

T. gondii. Higher levels of Th2-like cytokines IL-6 and IL-10 were produced in both ROP4 VLP and ROP18 VLP vaccinations, and Naïve+Cha compared to naïve (*

P <0.05), indicating both ROP4 VLP and ROP18 VLP vaccinations including Naïve+Cha induced Th2-like immune responses. Compare to ROP18 VLP vaccination, ROP4 VLP induced higher levels of IL-10 and IL-6 (*

P <0.05). These results indicated that ROP14 VLP or ROP18 VLP vaccination induced both Th1 and Th2-like cytokine responses, in which ROP18 VLP showed Th1 dominant immune response, whereas ROP4 VLP showed Th2 dominant immune response.

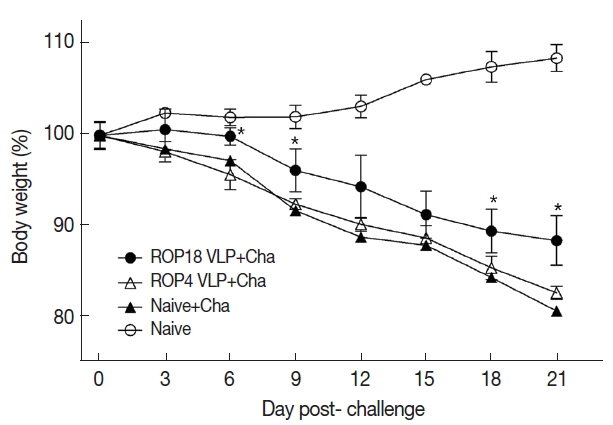

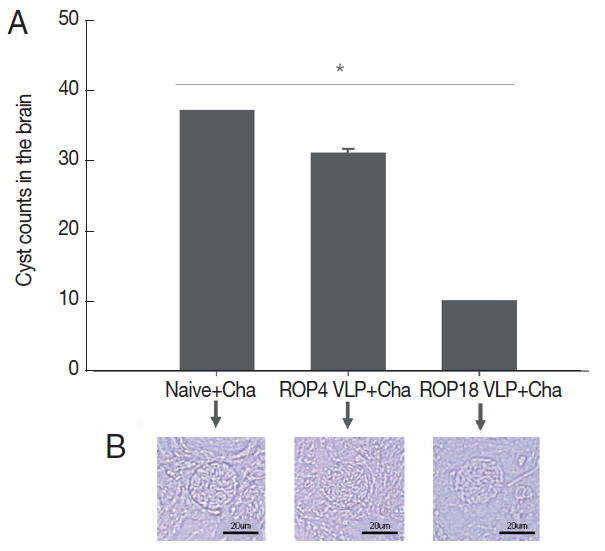

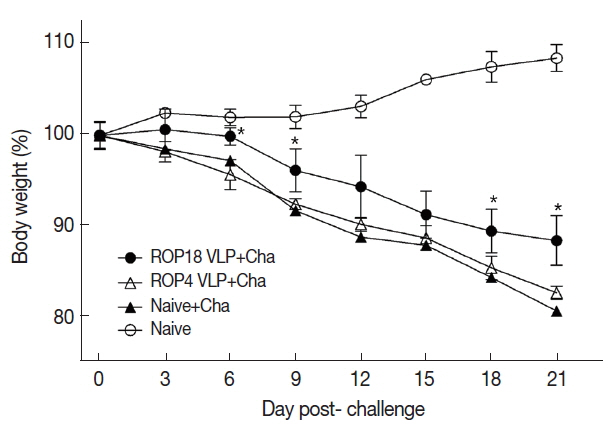

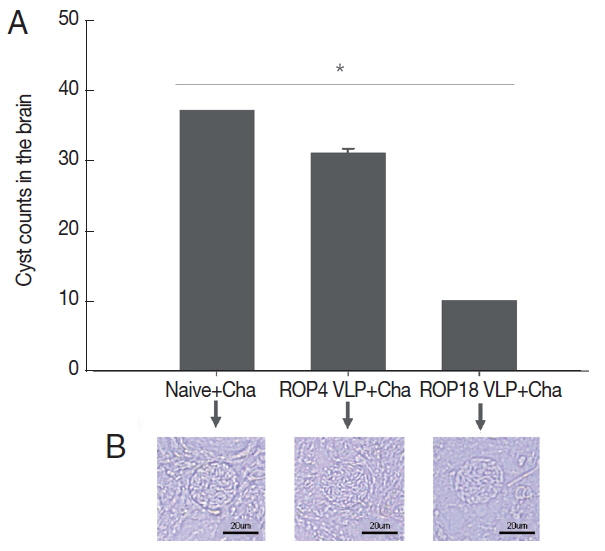

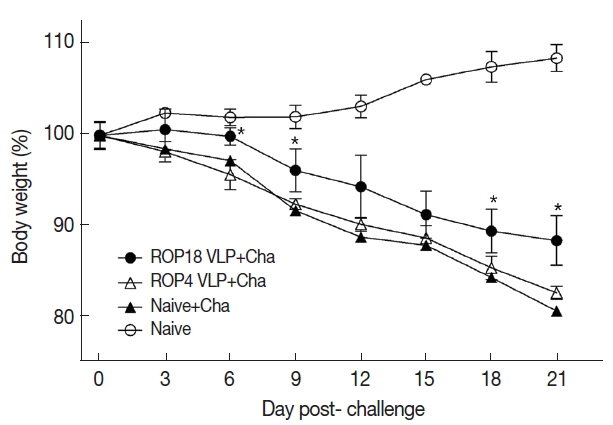

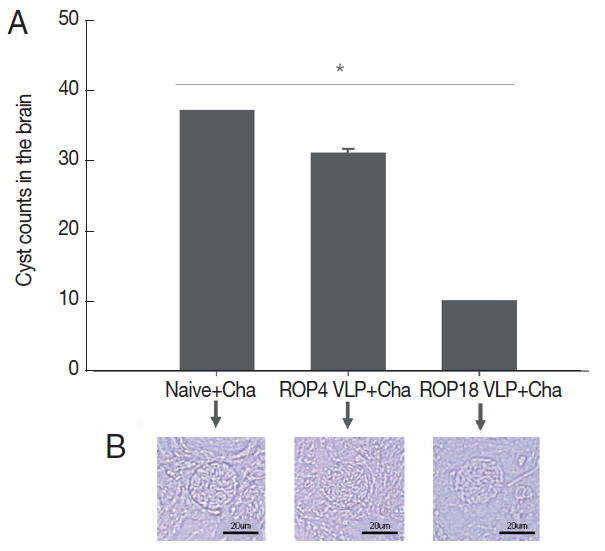

Cyst counts in the brain following challenge infection are the most important indicators to assess VLPs vaccine-induced protection. Immunized mice were orally challenge infected with

T. gondii ME49 cysts at 4 weeks after second boost. Cyst counts in brain were determined at 1 month post-challenge. As in

Fig. 5, ROP18 VLPs showed less body weight loss compared to ROP4 VLPs, indicating ROP18 VLPs induced better protection compared to ROP4 VLPs. Body weight of mice immunized with ROP 8 VLPs returned to normal range over time. However, naïve mice challenge infected continued to lose body weight and died. As shown in

Fig. 6A, ROP18 VLPs significantly reduced cyst counts (10.2 cyst) in brain upon challenge infection compared to non-immunized Naïve mouse control (36.3 cyst) and ROP4 VLPs (32 cyst), indicating that better protective efficacy was induced from ROP18 VLP vaccination than to ROP4 VLPs. No significant reduction of cyst sizes in the brain were found (

Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we generated T. gondii VLPs expressing ROP4 or ROP18 and compared the vaccine efficacies induced by these 2 VLPs vaccinations. Both ROP4 and ROP18 VLPs vaccination induced parasite-specific antibody responses, T cell responses and protection. Importantly, ROP18 VLP vaccination showed better protection compared to ROP4 VLPs.

Our results demonstrated that ROP18 VLP is more effective than ROP4 VLP in inducing parasite-specific IgA, IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody responses. ROP18 VLP immunization induces less body weight loss and significantly reduced cyst count in the brain compared to ROP4 VLPs. Interestingly, these antibody responses induced by ROP4 VLPs or ROP18 VLPs were gradually increased following prime and 1st boost, indicating immune system was boosted which might contribute to protection against ME49 challenge infection. Higher levels of IgA, IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody responses were found in ROP18 VLP vaccination, which might contribute to better protection induced by ROP18 VLP compared to ROP4 VLP. Intranasal immunizations with VLPs containing microneme protein 8 (MIC8) or inner membrane complex (IMC) from

T. gondii was proven to elicit IgA antibody responses in intestinal mucosa (feces) as well as IgG antibody responses in sera, indicating the induction of both mucosal and systemic responses [

8,

9]. This is consistent with the results we obtained from the present study.

In the present study, high dose of

T. gondii ME49 (1,500 cysts/mouse) was used for challenge infection which is much higher than that of

T. gondii (100/mouse) published [

10]. Thus, body weight of mice decreased gradually as time progressed and recovered on day 30 post-challenge infection. Interestingly, cyst sizes in the brain from immunized mice were not significantly reduced compared to non-immunized control. This is different from the previous studies where significant reductions of cyst sizes from immunized mice were observed [

10], indicating high dose of challenge infection may lead to less protective efficacy and resulted in no changes in cyst size. ROP18 as a kinase is a key virulence determinant conferring a high mortality phenotype of type I RH strains, mediating virulence and survival of the parasite by protecting the vacuolar membrane from destruction by the host [

16,

17]. In our current study, ROP18 VLPs were used as a vaccine (immunogen) to immunize mice and resulted in

T. gondii-specific antibody responses and showed better protection compared to ROP4 VLPs. These results indicated that ROP18 kinase as virus-like particle (VLP) platforms could be developed as potential vaccines against toxoplasmosis.

IgM is the first antibody isotype induced upon infection or immunization. Vaccine-induced IgM is able contribute to the early controlling of pathogens [

18,

19]. Thus, for the first time, we determined IgM antibody responses upon VLP vaccination. We found the level of IgM antibody response reached peak after 1st boost, which might contribute to protection against early infection of

T. gondii. Further study is needed to identify the role of IgM antibody response in VLP vaccination. Interestingly, ROP4 VLP or ROP18 VLP vaccination induced both Th1 and Th2-like cytokine responses in which ROP18 VLP vaccination induced higher levels of Th1-like cytokine responses than Th2-like responses. This is consistent with dominant antibody responses of IgG2a and IgG2b induced by ROP18 VLPs compared to ROP4 which might contribute to better protection induced by ROP18 VLPs. It is likely that activated T-helper cells activate B cells and the interaction between the T-helper cells and B-cells caused the B cells to differentiate into plasma cells and memory cells [

20]. Better protection was induced from ROP 18VLPs vaccination by significantly reduced cyst counts in the brain and less body weight loss compared to unimmunized Naïve+Cha control. ROP4 VLPs immunization showed similar level of body weight loss compared to unimmunized control, indicating ROP4 cannot be used a vaccine candidate by VLP formulation. The potential role of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells in conferring protective immunity needs to be investigated since increased CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells in immunized mice may contribute to the protection against

T. gondii ME49 challenge infections [

8,

9].

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2018R1A2B6003535, 2018R1A6A1A03025124) and Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ01320501), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Fig. 1Characterization of T. gondii ROP4 VLP, ROP18 VLPs and M1 VLPs. T. gondii ROP4, ROP18 VLPs and M1 VLPs (lane 1, 30 μg; lane 2, 6 μg) were loaded per lane, independently. T. gondii ROP4 protein (63 kDa; A), T. gondii ROP18 protein (61 kDa; B) and influenza M1 protein (28 kDa; A, B) were identified by western blot.

Fig. 2Animal experimental schedule. Animal experiment were performed as scheduled. Antibody responses, cytokine production and protection were determined.

Fig. 3

Toxoplasma gondii-specific antibody response. T. gondii-specific IgA (A), IgM (B), IgG (C), IgG1 (D), IgG2a (E), and IgG2b (F) antibody responses after prime, 1st boost and 2nd boost were determined. Data are expressed as mean±SD.

Fig. 4Cellular immune response. Immunized mice were challenge infected with T. gondii ME49, and at week 4 after challenge infections, mice were sacrificed as scheduled. Cytokines IFN-γ (A), IL-6 (B) and IL-10 (C) were determined as indicated (*P<0.05). Data are expressed as mean±SD.

Fig. 5Body weight reduction of Toxoplasma gondii infection in immunized mice. Mouse body weight changes from mice immunized with VLPs upon challenge infection were monitored. Data are expressed as mean±SD. Naïve+Cha: Naïve mice were challenge infected with ME49 cysts.

Fig. 6Changes in number of Toxoplasma gondii ME49 cyst in the brain. Immunized mice were orally challenge infected with cysts and sacrificed at week 4 after last immunization. Changes of cyst counts were counted in groups ROP18 VLP, ROP4 VLP and Naive+Cha. Data are expressed as mean±SD. Naive+Cha:Naive mice were challenge infected with ME49 cysts. à and Naive+Cha. (A) Data are expressed as mean±SD. Naive+Cha. (B)The cyst in the mouse brain of each experimental group.

References

- 1. Parlog A, Schlüter D, Dunay IR.

Toxoplasma gondii-induced neuronal alterations. Parasite Immunol 2015;37:159-170.

- 2. Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM.

Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int J Parasitol 2000;30:1217-1258.

- 3. Jones JL, Parise ME, Fiore AE. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: toxoplasmosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:794-799.

- 4. Goldstein EJC, Montoya JG, Remington JS. Management of Toxoplasma gondii infection during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:554-566.

- 5. Liu Q, Singla LD, Zhou H. Vaccines against Toxoplasma gondii: status, challenges and future directions. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012;8:1305-1308.

- 6. Yuan ZG, Zhang XX, Lin RQ, Petersen E, He S, Yu M, He XH, Zhou DH, He Y, Li HX, Liao M, Zhu XQ. Protective effect against toxoplasmosis in mice induced by DNA immunization with gene encoding Toxoplasma gondii ROP18. Vaccine 2011;29:6614-6619.

- 7. Kang SM, Song JM, Quan FS, Compans RW. Influenza vaccines based on virus-like particles. Virus Res 2009;143:140-146.

- 8. Lee DH, Lee SH, Kim AR, Quan FS. Virus-like nanoparticle vaccine confers protection against Toxoplasma gondii

. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161231.

- 9. Lee SH, Kim AR, Lee DH, Rubino I, Choi HJ, Quan FS. Protection induced by virus-like particles containing Toxoplasma gondii microneme protein 8 against highly virulent RH strain of Toxoplasma gondii infection. PLoS One 2017;12:e0175644.

- 10. Lee SH, Kang HJ, Lee DH, Kang SM, Quan FS. Virus-like particle vaccines expressing Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein 18 and microneme protein 8 provide enhanced protection. Vaccine 2018;36:5692-5700.

- 11. Lee SH, Lee DH, Piao Y, Moon EK, Quan FS. Influenza M1 virus-like particles consisting of Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein 4. Korean J Parasitol 2017;55:143-148.

- 12. Joyce BR, Queener SF, Wek RC, Sullivan WJ Jr. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2{alpha} promotes the extracellular survival of obligate intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii

. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:17200-17205.

- 13. Wang PY, Yuan ZG, Petersen E, Li J, Zhang XX, Li XZ, Li HX, Lv ZC, Cheng T, Ren D, Yang GL, Lin RQ, Zhu XQ. Protective efficacy of a Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein 13 plasmid DNA vaccine in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19:1916-1920.

- 14. Fang R, Feng H, Nie H, Wang L, Tu P, Song Q, Zhou Y, Zhao J. Construction and immunogenicity of pseudotype baculovirus expressing Toxoplasma gondii SAG1 protein in BALB/c mice model. Vaccine 2010;28:1803-1807.

- 15. Choi HJ, Yoo DG, Bondy BJ, Quan FS, Compans RW, Kang SM, Prausnitz MR. Stability of influenza vaccine coated onto microneedles. Biomaterials 2012;33:3756-3769.

- 16. Wek RC, Cavener DR. Translational control and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007;9:2357-2371.

- 17. Fentress SJ, Sibley LD. The secreted kinase ROP18 defends Toxoplasma’s border. Bioessays 2011;33:693-700.

- 18. Dorfmeier CL, Shen S, Tzvetkov EP, McGettigan JP. Reinvestigating the role of IgM in rabies virus postexposure vaccination. J Virol 2013;87:9217-9222.

- 19. Racine R, Winslow GM. IgM in microbial infections: taken for granted? Immunol Lett 2009;125:79-85.

- 20. Perrone LA, Ahmad A, Veguilla V, Lu X, Smith G, Katz JM, Pushko P, Tumpey TM. Intranasal vaccination with 1918 influenza virus-like particles protects mice and ferrets from lethal 1918 and H5N1 influenza virus challenge. J Virol 2009;83:5726-5734.