Abstract

A complicated case of echinococcosis with multiple organ involvement is reported in a 53-year-old businessman who frequently traveled overseas, including China, Russia, and Kazakhstan from 2001 to 2007. The patient was first diagnosed with a large liver cyst during a screening abdomen ultrasonography in 2011, but he did not follow up on the lesion afterwards. Six years later, dizziness, dysarthria, and cough developed, and cystic lesions were found in the brain, liver and lungs. The clinical course was complicated when the patient went through multiple surgeries and inadequate treatment with a short duration of albendazole without a definite diagnosis. The patient visited our hospital for the first time in August 2018 due to worsening symptoms; he was finally diagnosed with echinococcosis using imaging and serologic criteria. He is now on prolonged albendazole treatment (400 mg twice a day) with gradual clinical and radiological improvement. A high index of suspicion is warranted to early diagnose echinococcosis in a patient with a travel history to endemic areas of echinococcosis.

-

Key words: Echinococcosis, hydatid cyst, disseminated, intracranial

INTRODUCTION

Echinococcosis is a zoonotic parasitic infection caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm

Echinococcus [

1]. It is endemic in many parts of the world, including northern Africa, central Asia, Siberia, and western China. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated echinococcosis to be the cause of 19,300 deaths globally each year [

2]. In Korea, the first case of pulmonary echinococcosis was reported in 1983 [

3]. Since then, 38 echinococcosis cases have been reported, most from endemic areas. Among these cases, there were only 3 cases of disseminated echinococcosis, involving more than 2 organs [

4–

6]. Here, we report the case of a patient with disseminated cystic echinococcosis, who had a complicated clinical course due to a delayed diagnosis and treatment.

CASE DESCRIPTION

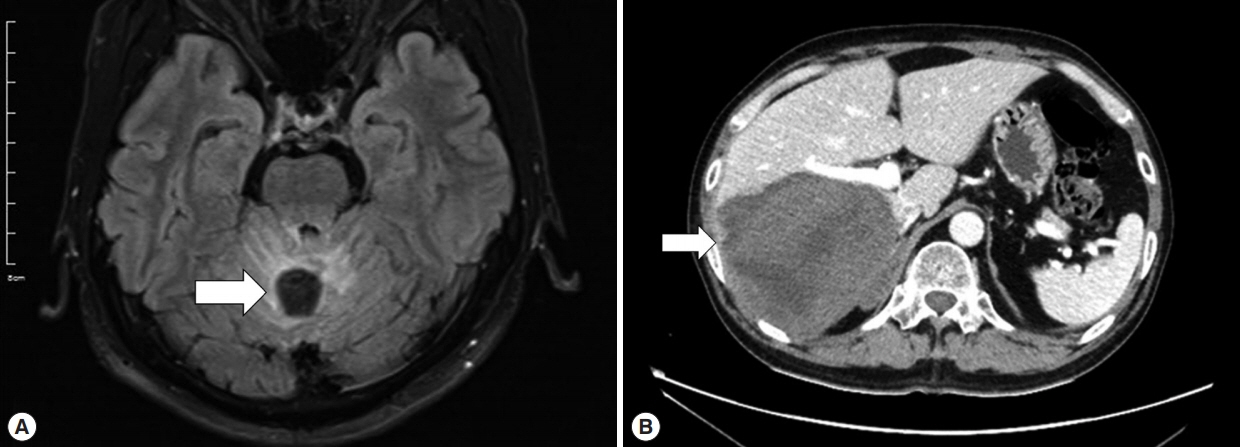

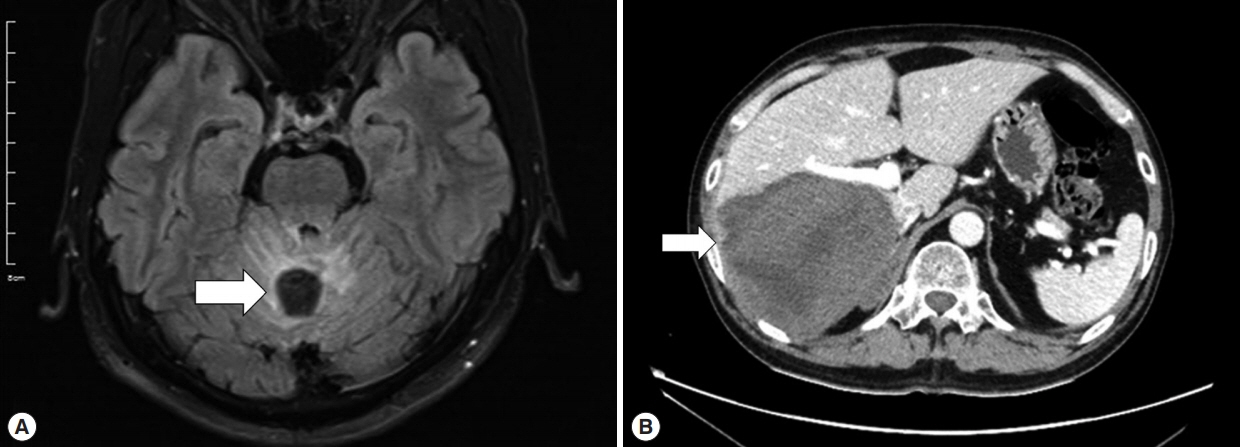

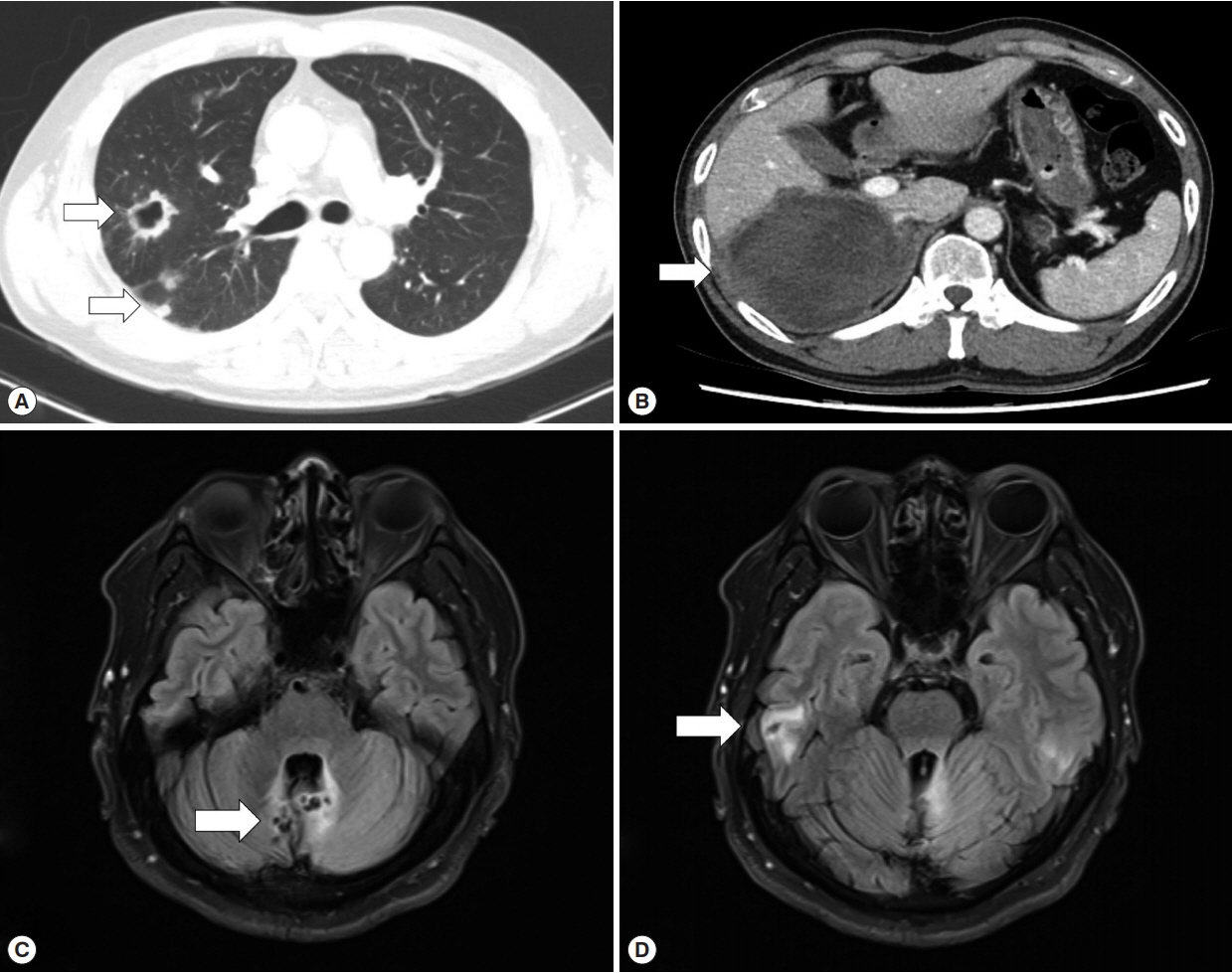

A 53-year-old businessman visited our hospital due to worsening dizziness and dysarthria starting 2 years ago. He had frequently traveled to China, Russia, and Kazakhstan between 2001 and 2007. He was previously healthy except for a history of tuberculous pleurisy 30 years ago. He was first diagnosed with a liver cyst (unknown size) by screening abdominal ultrasonography in a hospital in 2011. However, he did not follow up on the lesion. In April 2017, he visited another hospital because of non-whirling dizziness and dysarthria for several months. A 2 cm cerebellar mass and an 11.8 cm liver cyst were found in the brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and abdomen computed tomography (CT), respectively (

Fig. 1A, B). A stereotactic brain biopsy was attempted because a glioblastoma was suspected radiologically, but no tissue was obtained because of dense calcification. Craniotomy and mass removal were performed, and the pathologic exam revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with hyalinized bodies indicating parasitic infection, although no definite parasites were found. The presumptive diagnosis was neurocysticercosis, due to the positive result from the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for cysticercosis IgG (an unknown value). The patient took albendazole, 500 mg twice a day (14 mg/kg/day), for 52 days but his dizziness did not disappear. However, he did not visit the hospital of his own will.

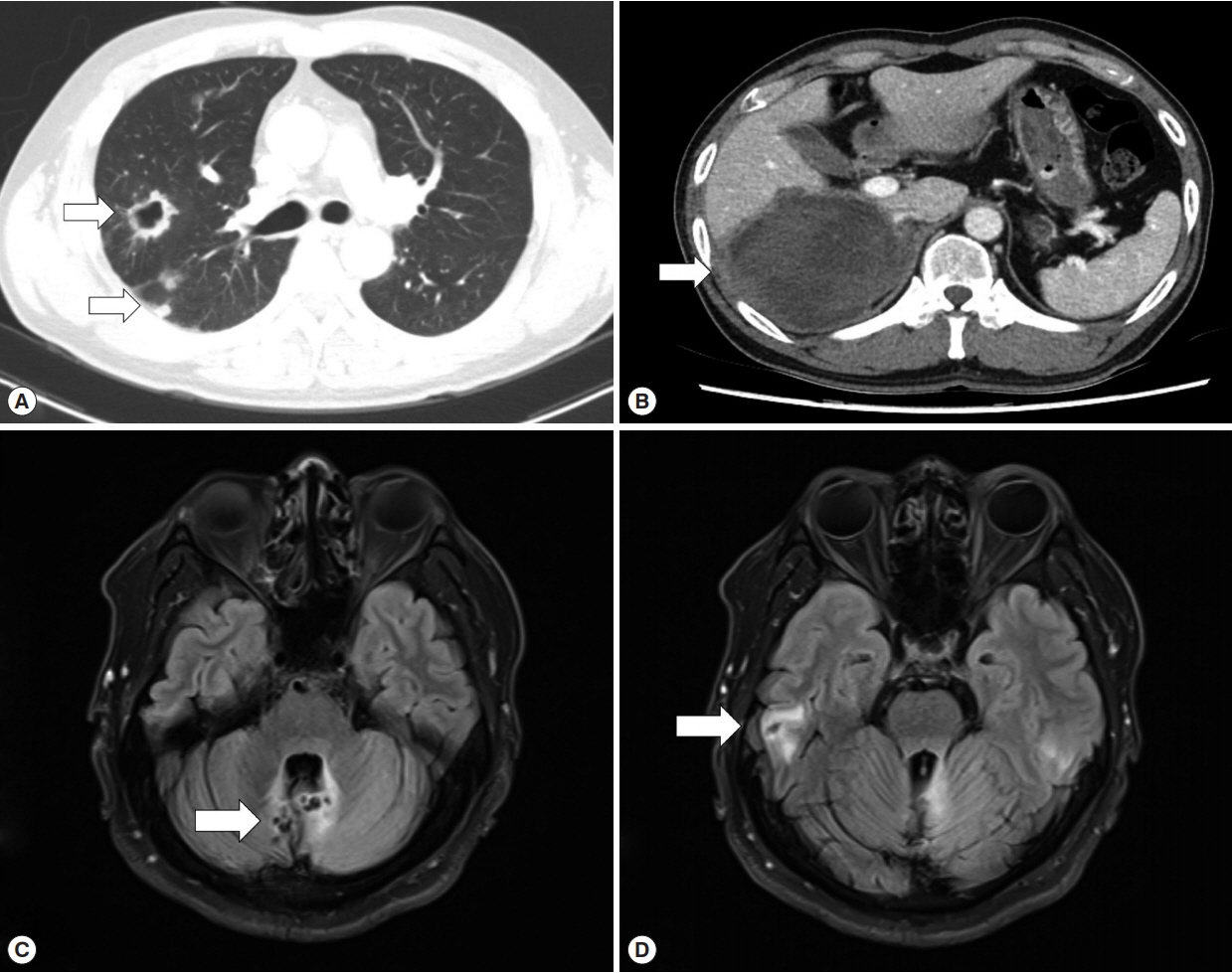

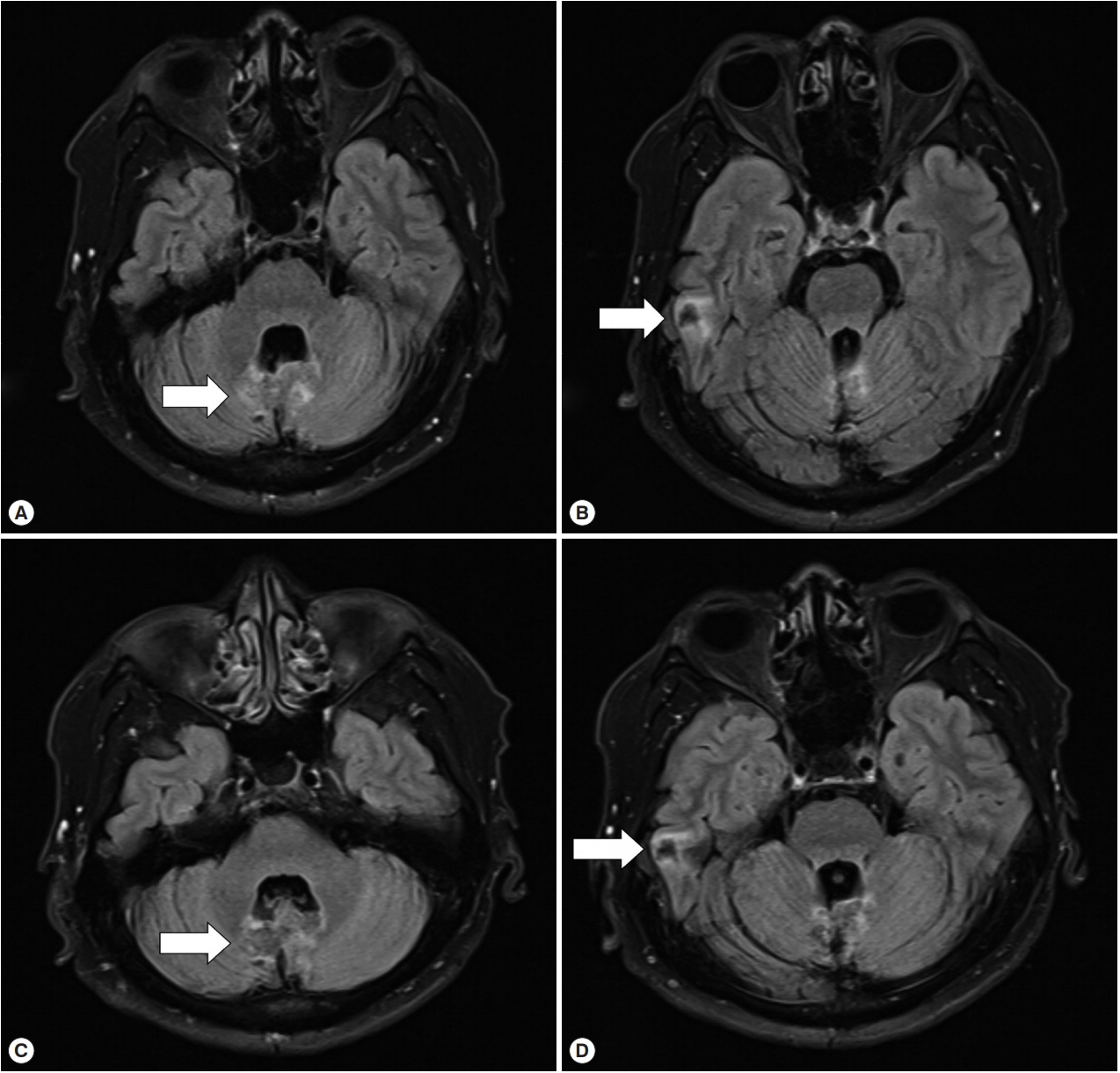

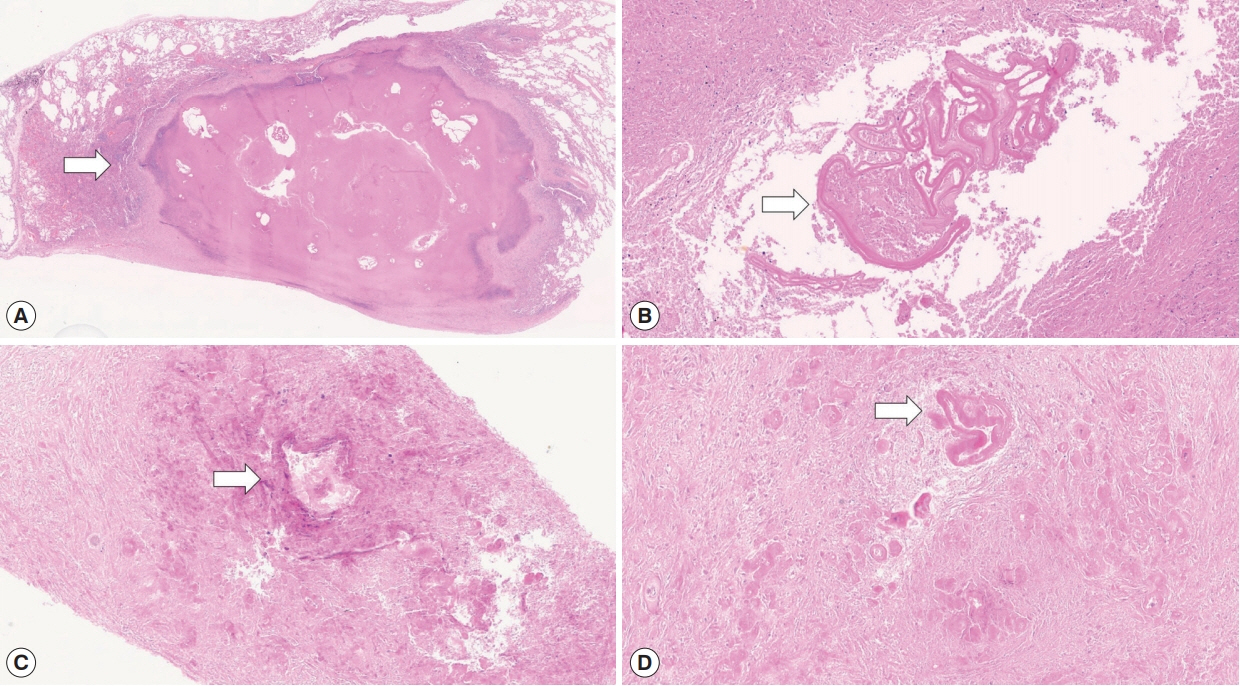

In April 2018, the patient visited another hospital because his dry cough had progressed. CT revealed multiple cystic lesions in both lungs and a 12.4 cm liver cyst involving the right adrenal gland (

Fig. 2A, B), and a follow-up brain MRI was performed that showed aggravated cerebellar lesions and a newly developed cystic lesion in the right temporal lobe (

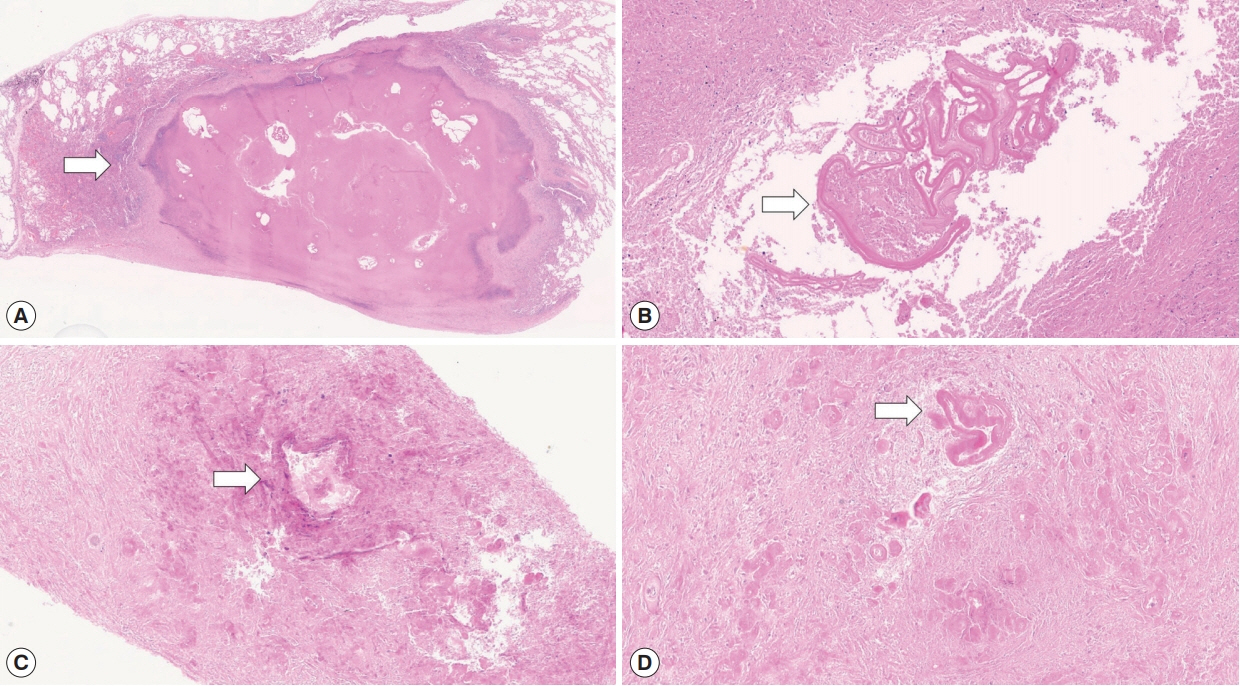

Fig. 2C, D). The patient underwent a right lower lobectomy, right hepatectomy, and right adrenalectomy because malignant disease was suspected. However, the histopathologic exams revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with the degenerated parasitic organism (

Fig. 3A–D). Praziquantel 1,200 mg 3 times a day (50 mg/kg/day) was prescribed for 14 days.

In August 2018, the patient visited our hospital because of worsening symptoms. This was the third university-affiliated hospital he had visited during the course. At admission, his vital signs and laboratory tests were all within normal limits except for mild elevation of eosinophils (white blood cell count 9,190/μl; segment neutrophils 66.2%, lymphocytes 20.9%, eosinophils 5.8%). Although IgG for cysticercosis was positive again (titer 0.704; cut-off 0.232) by ELISA [

7], the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was doubted because the size and shape of cysts in the liver, lung and brain were not consistent with those of cysticercosis using radiological approaches. Given the past travel history to endemic areas of echinococcosis and the multiple organ involvement of cysts with varying sizes, a serum ELISA for echinococcosis IgG was performed as previously described [

8], and turned out to be positive (titer 0.886; cut-off 0.270). The patient was finally diagnosed as probable cystic echinococcosis based on the diagnostic criteria [

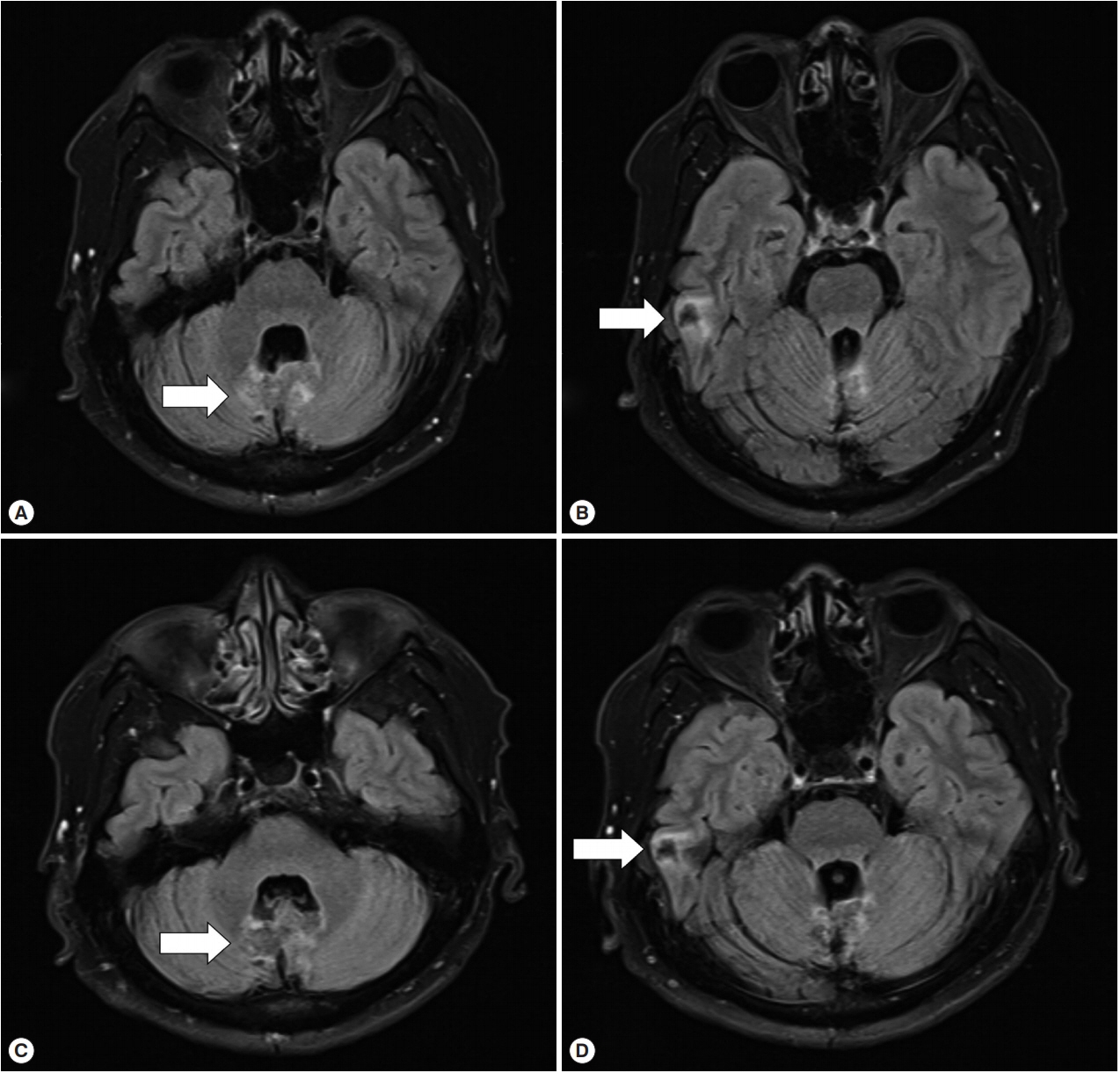

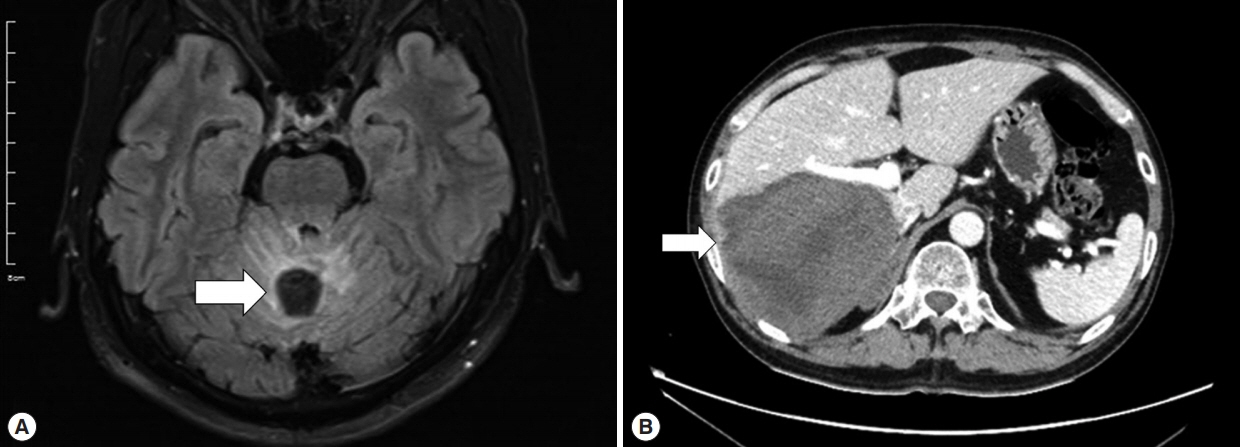

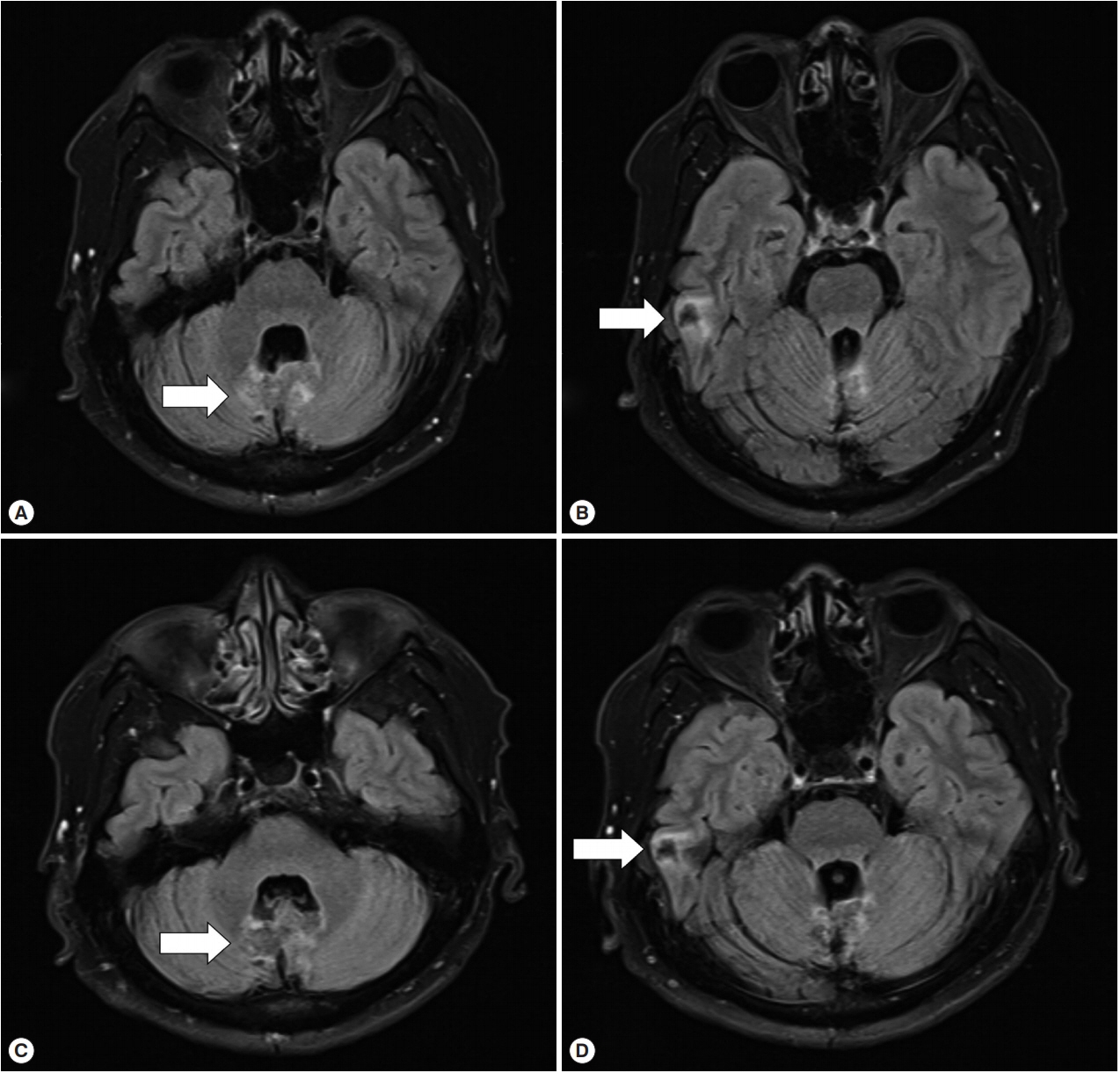

9]. Since it was technically difficult to excise all lesions from both cerebellar hemispheres and the temporal lobe, albendazole, 400 mg twice a day (10–15 mg/kg/day), was started. Worried about paradoxical worsening of neurological symptoms after the commencement of the treatment, we prescribed 4 mg of dexamethasone 4 times a day for 3 days, and then it had been tapered off over 10 days. His dizziness and dysarthria are gradually improving, and the cerebellar lesions are also radiologically improving at 2 (

Fig. 4A, B) and 7 months (

Fig. 4C, D) after the commencement of the therapy.

DISCUSSION

We have described a case of echinococcosis involving multiple organs that was complicated by a delayed diagnosis and treatment. Since echinococcosis is not prevalent in Korea, people are infected during travels to endemic areas and this makes an early diagnosis and proper management more challenging. The present case is the 4th disseminated case in Korea, and probably the most complicated, which underscores the importance of a high index of suspicion in a patient who has visited endemic areas of echinococcosis.

In Korea, 38 cases of echinococcosis have been reported since it was first described in 1983 [

4–

6,

10–

14]. Most cases involved the liver (22/38, 57.9%) or lung (10/38, 26.3%) only, while 3 involved multiple organs (3/38, 7.9%). Two of those three cases were cured by a resection operation [

6,

15]. However, one patient underwent repeated surgeries and was treated with long-term albendazole due to a delayed diagnosis because she had no history of travel to the endemic areas [

5]. The present patient had another complicated case of disseminated echinococcosis. However, the patient had an extensive travel history to endemic area of echinococcosis; thus, one of the previous physicians should have considered this possibility.

If a patient with a large liver cyst had a travel history to endemic areas, echinococcosis should have been placed on the list of differentials and follow-up tests performed regularly. Also, it is important to ask the patient about close contact with a dog, which is a major route of infection by the tapeworm

Echinococcus [

16]. Since the cystic lesion of echinococcosis grows slowly and it may take several years before it is diagnosed [

17], it is necessary to explore the exposure or travel history of the patient several years before detection of the hydatid cyst.

The next issue is to differentiate between echinococcosis and cysticercosis. Imaging procedures such as CT and MRI can easily differentiate the metacestode of

Taenia solium (cysticercus) from a hydatid cyst. In neurocysticercosis, cysts of

T. solium appear as small, round areas with the scolex within the cyst, and are easily distinguished from parenchyma of the brain. When cysts are degenerating, they show ill-defined margin and tend to be surrounded by edema [

18]. In contrast, lesions of echinococcosis are presented as tumor-like masses with varying sizes, usually bigger than those of the cysts of

T. solium, and the lesions have irregular margins, heterogeneous internal structures, and calcifications on CT [

19]. In the present case, there were no cystic lesions showing the scolex on brain MRI [

20], and a huge liver cyst larger than 5 cm was far more accordant with echinococcosis [

9,

21]. In this regard, the diagnosis should have been made more prudently.

Currently, serological diagnosis by ELISA is performed to detect infection by 4 major tissue parasites in Korea, which includes

Clonorchis sinensis, Paragonimus westermani, the metacestode of

Taenia solium, and sparganum. Therefore, without suspicion, the diagnosis of echinococcosis would be difficult by conventional ELISA as it does not include the detection of antibodies against the tapeworm

Echinococcus. The positive result of IgG for cysticercosis in this case might be a cross-reaction with echinococcosis, and this made the diagnosis more difficult [

22].

Suspecting echinococcosis prior to a surgery or a procedure is crucial because spillage of viable parasite material may cause anaphylactic reactions or secondary cystic echinococcosis [

9]. During the patient’s first operation, the hydatid cyst might have spilled and led to more metastatic infections of the lungs and brain. Treatment options for cystic echinococcosis include surgery, percutaneous treatment, and drugs. Although surgery or percutaneous treatment are more preferred options, albendazole is often used as an adjunctive therapy after surgery or percutaneous treatment, or as a definitive therapy for small lesions [

9,

23–

25]. However, there are some reports where inoperable disseminated or cerebral echinococcosis has been treated with a prolonged (at least 6 months) course of albendazole [

9,

26–

28]. Fifty-two days of albendazole treatment after the first hospital visit might not have been sufficient for echinococcosis in the present case. Since it was impossible to excise all lesions in the present case, we decided to treat the patient with long-term albendazole, and he is now gradually improving both clinically and radiologically.

In conclusion, we presented a case of disseminated echinococcosis complicated by a delayed diagnosis and treatment. Considering a patient’s history of travels to endemic areas and having a high index of suspicion are crucial factors for an early diagnosis of echinococcosis.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Seoul National University Hospital.

Fig. 1Cystic lesions in the liver and cerebellum in 2017. (A) MRI T2 sequencing showed a 2 cm peripheral enhancing mass (arrow) in the cerebellum. (B) Liver CT, with portal vein enhancement, showed an 11 cm lobulated mass (arrow) in the right posterior section of the liver.

Fig. 2Cystic lesions in the lung, liver, and brain in April 2018. (A) Chest CT showed multiple cystic to nodular lesions (arrows). (B) Liver CT, with portal vein enhancement, showed a 12.4 cm lobulated mass (arrow). (C, D) Brain MRI T2 sequencing showed new cystic lesions in the cerebellum and right temporal lobe (arrow).

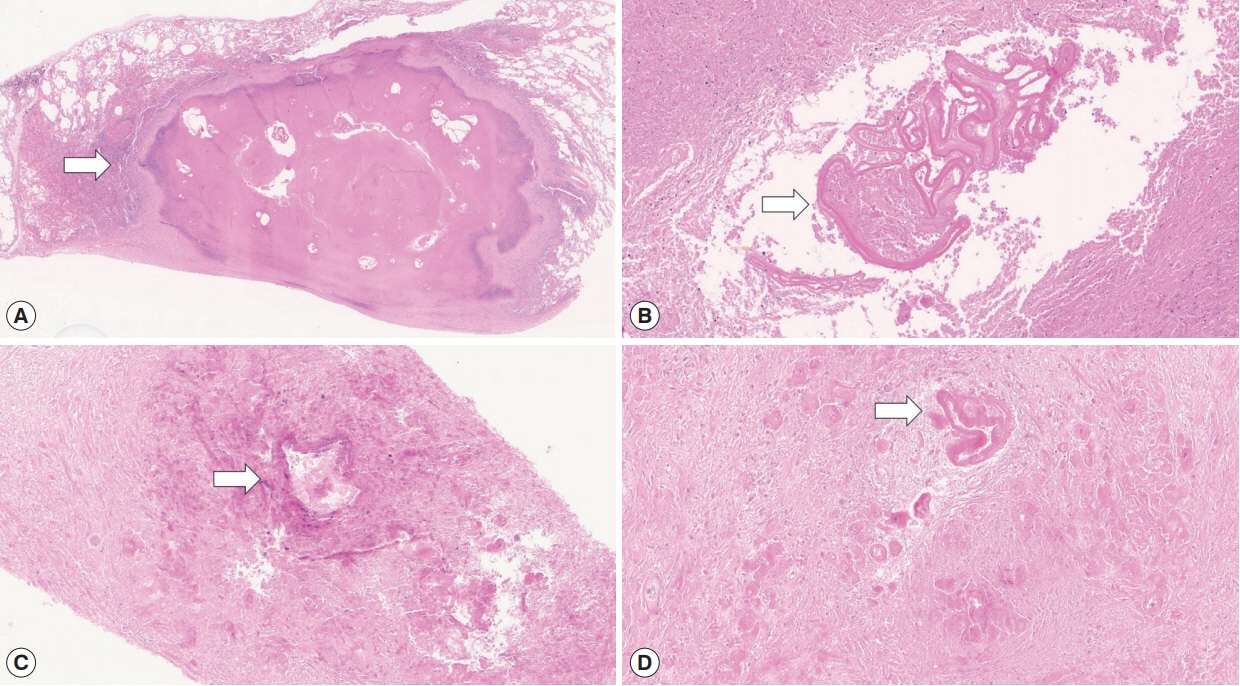

Fig. 3Pathologic exams of the resected lung tissue (A, B), and liver (C, D). (A) A demarcated lesion with extensive necrosis is observed (arrow). (B) High-power view reveals lamellated cyst wall with accompanied granulomatous inflammation (arrow). (C) A near-totally necrotic tissue with vague cyst-forming lesion (arrow). (D) High-power view reveals some amorphous hyalinized eosinophilic bodies (arrow).

Fig. 4Treatment response on the intracranial lesions. The brain MRI T2 sequencing images showing slight improvement of cystic lesions and perilesional edema (arrow) (A, B) in October 2018 and (C, D) in March 2019.

References

- 1. Lightowlers MW. Cysticercosis and echinococcosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;365:315-335.

- 2. Hald T, Aspinall W, Devleesschauwer B, Cooke R, Corrigan T, Havelaar AH, Gibb HJ, Torgerson PR, Kirk MD, Angulo FJ, Lake RJ, Speybroeck N, Hoffmann S. World Health Organization estimates of the relative contributions of food to the burden of disease due to selected foodborne hazards: a structured expert elicitation. PLoS One 2016;11:e0145839.

- 3. Chung KY, Lee DY, Hong PW, Chung HJ, Choi IJ, Min DY. Surgical treatment of pulmonary hydatid cysts: two cases report. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983;16:518-525. (in Korean)..

- 4. Byun SJ, Moon KC, Suh KS, Han JK, Chai JY. An imported case of echinococcosis of the liver in a Korean who traveled to western and central Europe. Korean J Parasitol 2010;48:161-165.

- 5. Kim SJ, Kim JH, Han SY, Kim YH, Cho JH, Chai JY, Jeong JS. Recurrent hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: report of the first case in Korea with unproven infection route. Korean J Parasitol 2011;49:413-418.

- 6. Ahn MH. Imported parasitic diseases in Korea. Infect Chemother 2010;42:271-279. (in Korean)..

- 7. Cho SY, Kim SI, Kang SY, Choi DY, Suk JS, Choi KS, Ha YS, Chung CS, Myung HJ. Evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in serological diagnosis of human neurocysticercosis using paired samples of serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Korean J Parasitol 1986;24:25-41.

- 8. Jin Y, Anvarov K, Khajibaev A, Hong SM, Hong ST. Serodiagnosis of echinococcosis by ELISA using cystic fluid from Uzbekistan sheep. Korean J Parasitol 2013;51:313-317.

- 9. Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 2010;114:1-16.

- 10. Kim SJ, Jung KH, Jo WM, Kim YS, Shin C, Kim JH. A case of pleural hydatid cyst mimicking malignancy in a non-endemic country. Tuberc Respir Dis 2011;70:338-341.

- 11. Ahn KS, Hong ST, Kang YN, Kwon JH, Kim MJ, Park TJ, Kim YH, Lim TJ, Kang KJ. An imported case of cystic echinococcosis in the liver. Korean J Parasitol 2012;50:357-360.

- 12. Kim AR, Park SJ, Gu MJ, Choi JH, Kim HJ. Fine needle aspiration cytology of hepatic hydatid cyst: a case study. Korean J Pathol 2013;47:395-398.

- 13. Choi H, Park JY, Kim JH, Moon DG, Lee JG, Bae JH. Primary Renal Hydatid Cyst: Mis-Interpretation as a Renal Malignancy. Korean J Parasitol 2014;52:295-298.

- 14. Kwon BW, Park SJ, Kong JH, Song IH. Daughter cysts in a cyst of the liver: hepatic echinococcosis. Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:197-198.

- 15. Jung BH, Kim TH, Kang JS, Chang K, Jeong ET, Chae KM, Choi SH, Moon HB. A case of pulmonary and hepatic hydatid cystic disease. Korean J Med 1993;45:550-556. (in Korean)..

- 16. Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:125-133.

- 17. Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 9th ed.. Philadelphia, USA. Lea & Febiger; 1984, pp 527-537.

- 18. Gripper LB, Welburn SC. Neurocysticercosis infection and disease-a review. Acta Trop 2017;166:218-224.

- 19. Bulakci M, Kartal MG, Yilmaz S, Yilmaz E, Yilmaz R, Sahin D, Asik M, Erol OB. Multimodality imaging in diagnosis and management of alveolar echinococcosis: an update. Diagn Interv Radiol 2016;22:247-256.

- 20. Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC Jr, Tsang VC, Nash TE, Takayanagui OM, Schantz PM, Evans CA, Flisser A, Correa D, Botero D, Allan JC, Sarti E, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH, García HH. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 2001;57:177-183.

- 21. Giri S, Parija SC. A review on diagnostic and preventive aspects of cystic echinococcosis and human cysticercosis. Trop Parasitol 2012;2:99-108.

- 22. Garcia HH, Castillo Y, Gonzales I, Bustos JA, Saavedra H, Jacob L, Del Brutto OH, Wilkins PP, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH. Low sensitivity and frequent cross-reactions in commercially available antibody detection ELISA assays for Taenia solium cysticercosis. Trop Med Int Health 2018;23:101-105.

- 23. Nabarro LE, Amin Z, Chiodini PL. Current management of cystic echinococcosis: a survey of specialist practice. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:721-728.

- 24. Dogru D, Kiper N, Ozcelik U, Yalcin E, Gocmen A. Medical treatment of pulmonary hydatid disease: for which child? Parasitol Int 2005;54:135-138.

- 25. Todorov T, Mechkov G, Vutova K, Georgiev P, Lazarova I, Tonchev Z, Nedelkov G. Factors influencing the response to chemotherapy in human cystic echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ 1992;70:347-358.

- 26. Chen S, Li N, Yang F, Wu J, Hu Y, Yu S, Chen Q, Wang X, Wang X, Liu Y, Zheng J. Medical treatment of an unusual cerebral hydatid disease. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:12.

- 27. Gana R, Skhissi M, Maaqili R, Bellakhdar F. Multiple infected cerebral hydatid cysts. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:591-593.

- 28. Ntusi NA, Horsfall C. Severe disseminated hydatid disease successfully treated medically with prolonged administration of albendazole. QJM 2008;101:745-746.