Abstract

This study aimed to investigate metacercarial infections in the wrestling halfbeak, Dermogenys pusilla, collected from Bangkok metropolitan region of Thailand. A total of 4,501 fish from 78 study sites were commonly examined with muscle compression and digestion methods (only head part of fish) during September 2017 to July 2018. The overall prevalence of metacercarial infection was 86.1% (3,876/4,501 individuals), and the mean intensity was 48.9 metacercariae per fish infected. Four species, i.e., Posthodiplostomum sp., Stellantchasmus falcatus, Cyathocotylidae fam. sp., and Centrocestus formosanus, of digenetic trematode metacercariae (DTM) were detected. The prevalences were 65.8%, 52.0%, 2.1%, and 1.2%, respectively and their mean intensities were 23.1, 51.6, 1.4, and 3.2 per fish infected, respectively. The seasonal prevalences were 81.0% in winter, 87.8% in summer and 87.4% in rainy, and the mean intensities were 38.9, 46.6, and 55.2 metacercariae per fish infected, respectively. Conclusively, it was confirmed that the wrestling halfbeak play the role of second intermediate hosts of 4 species of digenetic trematodes including S. falcatus and Posthodiplostomum sp. in Bangkok metropolitan region. And then the metacercariae of C. formosanus and Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. are to be first found in the wrestling halfbeak by this study.

-

Key words: Metacercariae, prevalence, wrestling halfbeak, heterophyid, diplostomid, cyathocotylid

INTRODUCTION

The parasitic infections in humans and animals can be transmitted by freshwater fish that act as a second intermediate host. Currently, fish-borne zoonotic trematodes are still the cause of health problems and also affect the public health of Thailand, especially in the northern and northeast region. People are infected with many types of flukes from freshwater fish, especially the intestinal fluke in the heterophyid group, such as

Centrocestus formosanus, Haplorchis pumilio, H. taichui, and

Stellantchasmus falcatus [

1]. Humans and some kinds of animals such as rats, cats, dogs, and fish-eating birds have been reported as a definitive host of these flukes. The consumption of raw or partially cooked freshwater fish containing metacercariae can cause parasitic diseases in humans and animals [

2]. In the northern part of Thailand that comprises the endemic areas, especially Chiang Mai or Lamphun provinces, there is high infection of parasites in the wrestling halfbeak [

3–

6]. Hence, in this study, we focused on the wrestling halfbeak because it seems to be the second intermediate host of many parasitic trematodes such as

S. falcatus and

Posthodiplostomum sp. [

3–

6]. Recently, Wongsawad et al. [

7] reported

Stellantchasmus dermogenysi from wrestling halfbeak, the morphological characteristics of

S. dermogenysi are similar to

S. falcatus from mullet,

Chelon macrolepis, but minor difference was noted including the absence of the prepharynx, smaller body size, and shorter esophageal length. In addition, a phylogenetic reconstruction suggests that

S. dermogenysi is separated from

S. falcatus.

The wrestling halfbeak (Dermogenys pusilla) is classified in the family Hemiramphidae. It is a small and slender fish with an elongated lower jaw, characteristic for this family. This fish is native to the fresh and brackish waters of rivers. It is found to be widely distributed in many freshwater resources around Bangkok metropolitan region, but there have not been any reports about parasitic infections in this fish. So, it is interesting to study the parasitic infections in the wrestling halfbeak outside the epidemic area. In addition, metacercariae were identified using molecular techniques because phylogenetic analyses of internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) rDNA sequences have successfully been used to resolve evolutionary relationships among closely related species.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated metacercarial infections in the second intermediate host (wrestling halfbeak) collected from Bangkok metropolitan region of Thailand, using morphological and species identification by molecular techniques. This would be the basic information for further management to prevent the spread of parasites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and investigation of metacercariae

The wrestling halfbeak (

D. pusilla) were randomly collected using hand nets from 78 study sites located in Bangkok metropolitan region (Bangkok, Nakhon Pathom, Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani, Samut Prakan, and Samut Sakhon) (

Fig. 1) in each 4 months: September 2017, January, April, and July 2018.

All collected fish were placed in an icebox and transferred to the laboratory at Animal Systematics and Ecology Speciality Research Unit, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand. The total length and width of all fish specimens were measured. The metacercariae were separately examined from the head, abdominal cavity, and muscles using compression technique, as described by Chanawong [

8].

In brief, the fish were pressed between a couple of glass slides or petri dishes in order to find metacercariae under a stereomicroscope. The head which is location of some metacercaria was digested using an acid-pepsin solution (concentrated hydrochloric acid 1 ml; pepsin 1 g; 0.85% sodium chloride solution 99 ml) for 2 hr at 37°C [

4]. Thereafter, the digested material was rinsed with 0.85% sodium chloride solution and observed for metacercariae. The metacercariae were collected, counted, recorded, and preserved in absolute ethanol for DNA investigation. Some encysted metacercariae was excysted with a trypsin-bile salts-cysteine (TBC) medium [

9] and stained with 0.5% neutral red (dilution 1:10) and carefully examined under a light microscope. The metacercariae were identified in terms of species according to the morphological characters as described by Chai [

10], Sohn [

11], and Gibson [

12]. Then, the prevalence (%) and mean intensity of infection (the number of metacercariae per infected fish) were calculated.

The genomic DNAs of metacercarial samples were extracted using GF-1 Tissue DNA Extraction Kit (Vivantis, Subang Jaya, Malaysia) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Extracted DNA samples were stored at −20°C until used.

PCR amplification of partial ITS2 fragment was done as described previously [

5]. It was performed using 2 primers, ITS3: 5′GCA TCG ATG AAG AACGCA GC 3′ as a forward primer and ITS4: 5′TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC 3′ as a reverse primer. PCR reaction was carried out in volume of 25 μl, consisting of 1×PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl

2, 0.1 mM of each dNTP, 0.4 μM of each primer, and 2 U/μl of

Taq DNA polymerase (Vivantis, Malaysia).

Conditions of PCR were set in a thermal cycler (Mastercycler Pro; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) as follows: 5 min at 94°C for initial denaturation, 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C for denaturation, 1 min at 56°C for annealing, and 30 sec at 72°C for extension. Finally, 10 min at 72°C was set for final extension. PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gel at and stained with SYBR Safe (Invitrogen) DNA gel stain and photographed using a Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR system (Bio-Rad).

Phylogenetic analyses

The PCR products were purified and sequenced of Macrogen, (Seoul, Korea), using the same primers used in PCR reaction. The sequences were checked using the standard nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) database to confirm the PCR target. The electropherogram of each sequence were examined for sequence accuracy, using Geneious Prime. The multiple alignment of sequences (~400 bp) was performed using ClustalW. The DNA sequence data of 4 trematodes from this study and other related species form GenBank databased (accession nos.: KU753590.1, KU753585.1, KX931428.1, MH521251.1, KY075665.1, AY245707.1, MH521249.1, and HM 064954.1) were used for constructing phylogenetic relationships of using the neighbor-joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods in MEGA7 program. The reliability of the internal branches was assessed using bootstrap resampling with 10,000 replicates.

RESULTS

Infection of metacercariae in fish

A total of 4,501 wrestling halfbeak were collected from 78 study sites located in Bangkok metropolitan region. The overall prevalence of infection was 86.1% (3,874/4,501 individuals), and the mean intensity was 48.93 metacercariae per fish infected. The metacercarial infection in each province showed that Samut Prakan province had the highest infection. It was high in both the prevalence (95.7%) and the mean intensity (100.5 metacercariae per fish infected), followed by Samut Sakhon, Pathum Thani, Nonthaburi, Nakhon Pathom, and Bangkok, with the prevalence of 90.6%, 89.8%, 85.4%, 78.1%, and 76.2%, respectively (

Table 1).

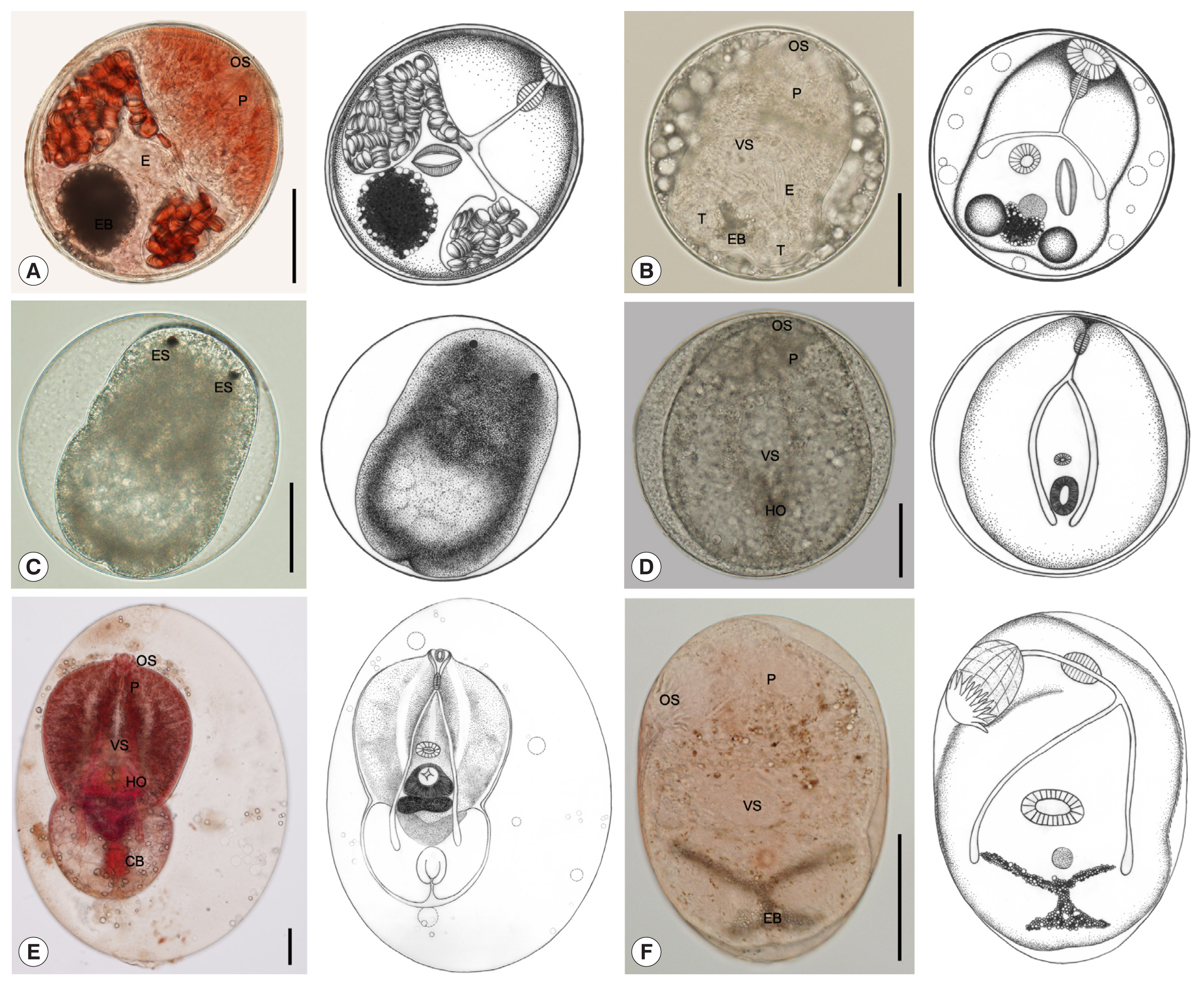

The wrestling halfbeak were highly susceptible hosts for metacercarial infections. Four species of metacercariae were found in this fish.

Stellantchasmus falcatus metacercariae had the highest infection of all metacercariae at about 63.7%. The muscles harbored the highest number of metacercariae, followed by the abdominal cavity and head. Metacercariae varied in morphology depending on the developmental stage (

Fig. 2A–D). They were elliptical and 212×188 μm in average size. The excretory bladder was round or oval shaped, with dark granules inside. The larva inside had the genital atrium with long expulsor (seminal vesicle). Metacercariae of

S. falcatus were collected in 2,341 (52.0%) out of 4,501 fish, and their mean intensity was 51.6 per fish infected (

Table 2).

The amount of

Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercariae was 36.1% of all metacercariae and located only in the abdominal cavity. They were large neascus metacercariae, elliptical with thin wall, and 816×499 μm in average size. The larva body inside was split into 2 parts: (1) a forebody and (2) a hindbody (

Fig. 2E). Metacercariae of

Posthodiplostomum sp. were collected in 2,960 (65.8%) out of 4,501 fish, and their mean intensity was 23.1 per fish infected (

Table 2).

They were followed by Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. (0.1% of all metacercariae), which were found only in the muscles. They were round Prohemistomulum metacercariae and 313×300 μm in average size. The metacercaria wall was thin, and a holdfast organ was observed (

Fig. 2D). Metacercariae of Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. were collected in 96 (2.1%) out of 4,501 fish, and their mean intensity was 1.4 per fish infected (

Table 2).

The least of metacercarial infection was found in

C. formosanus (0.1% of all metacercariae). The metacercariae were found only in the gill filaments. They were elliptical and 261×182 μm in average size. They presented an X-shaped excretory bladder with dark granules inside and 32 circumoral spines in 2 rows surrounding the oral sucker (

Fig. 2F). Metacercariae of

C. formosanus were collected in 54 (1.2%) out of 4,501 fish, and their mean intensity was 3.2 per fish infected (

Table 2).

The infection rate varied with seasons. A high infection rate was found during both summer (April–May) and rainy (June–October) seasons, with a prevalence greater than 87%, whereas the highest mean intensity was found during the rainy season at about 55.2 metacercariae per fish infected. The winter season (November–March) had the lowest infection rate of about 81.0% and the mean intensity was 38.9 metacercariae per fish infected (

Table 3).

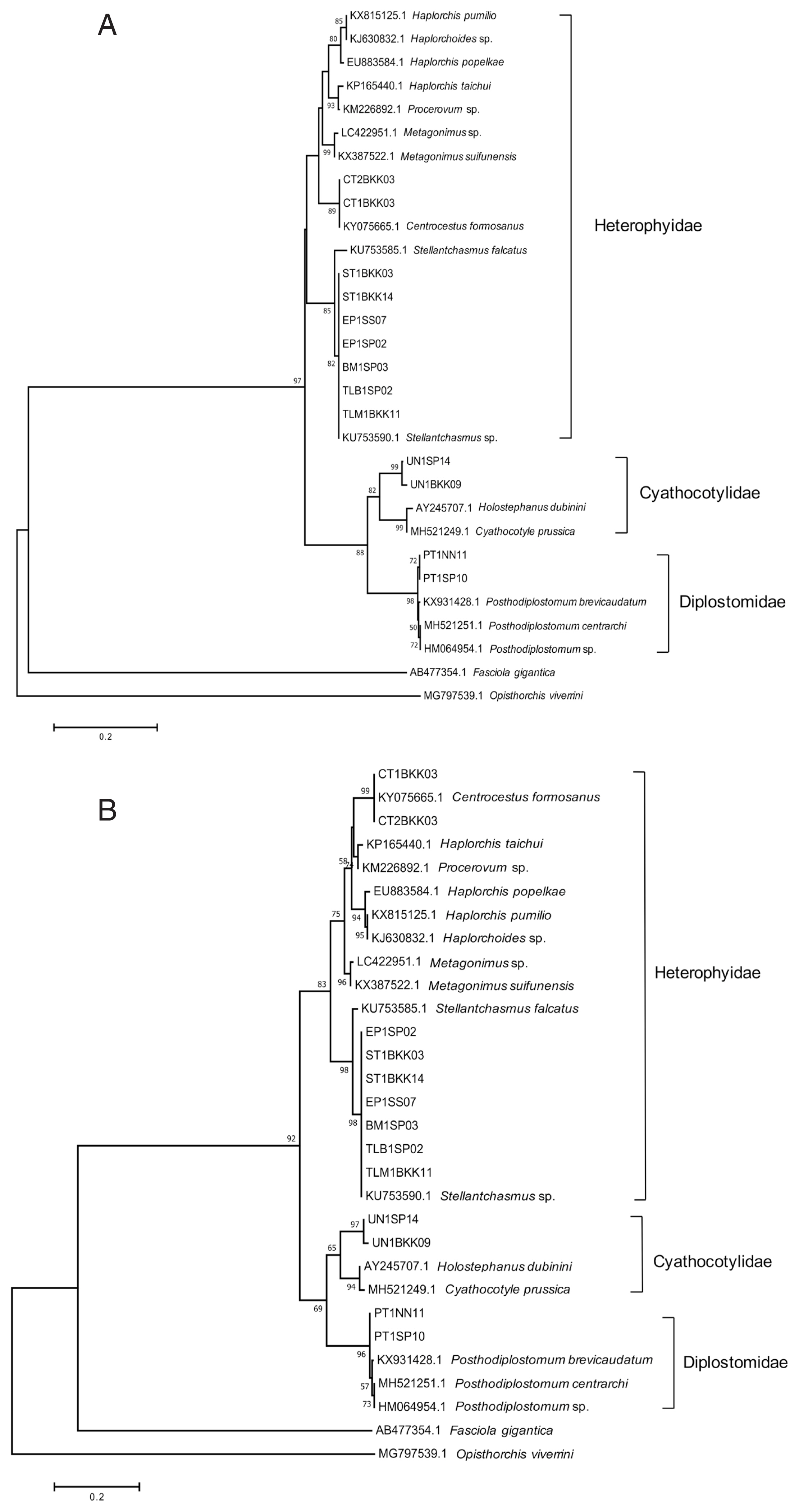

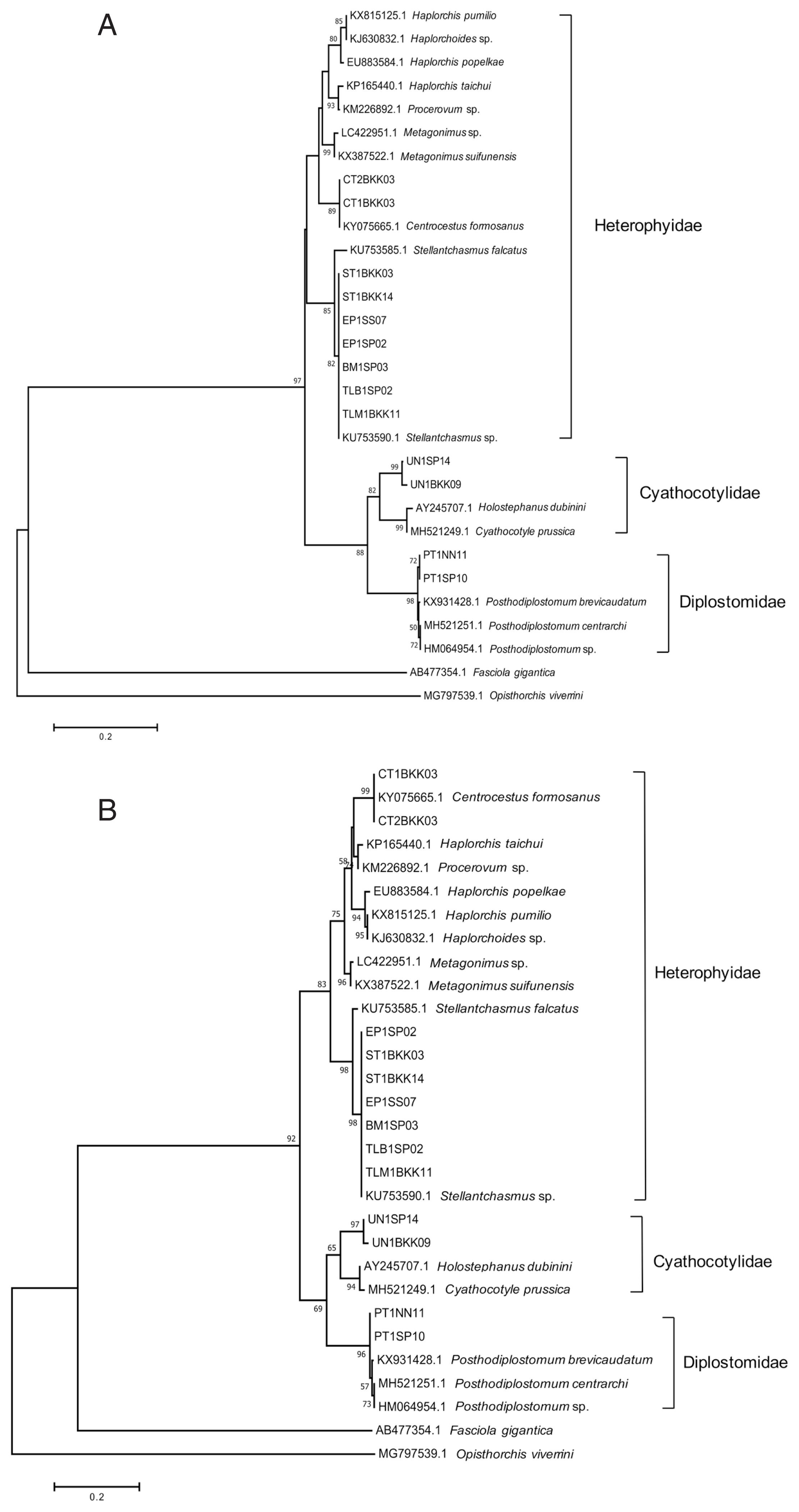

The sequence data of the ITS2 region from

S. falcatus, C. formosanus, Posthodiplostomum sp., and Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. were approximately 432, 396, 394, and 398 bp, respectively. The BLAST check results showed 4 species of intestinal trematodes in this study, including

S. falcatus (similarity ~94%),

C. formosanus (similarity ~97–98%), and

Posthodiplostomum centrarchi (similarity ~96%), and

Holostephanus dubinini (similarity ~86%). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using ML and NJ methods, with bootstrap values of 10,000 replicates. Both methods showed the similar topology that 4 species of metacercariae originated from 3 families. The trematodes were separated into 2 groups of family, including the family Heterophyidae and superfamily Diplostomoidea.

Stellantchasmus falcatus and

C. formosanus were classified as the family Heterophyidae. The trematodes in the family Heterophyidae appeared to be in a monophyletic clade. The heterophyids were separated into 2 sister groups, including the

S. falcatus group and another heterophyid group. In addition, the superfamily Diplostomoidea was divided into 2 groups, including the family Cyathocotylidae and family Diplostomidae.

Holostephanus dubinini was classified as the family Cyathocotylidae and

P. centrarchi was classified as the family Diplostomidae (

Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Investigations of the infection rates of metacercariae in the wrestling halfbeak were performed in combination with studies on identification using molecular techniques. The results of this study showed that the overall prevalence of infection was 86.1% (3,874/4,501 individuals) and the mean intensity was 48.9 metacercariae per fish infected. Among the study sites, Samut Prakan province had the highest prevalence and mean intensity of infection, followed by Samut Sakhon, Pathum Thani, Nonthaburi, and Nakhon Pathom. The least infection was found in Bangkok. Comparing with Sripalwit et al. [

4], they found a high infection rate of metacercariae in the wrestling halfbeak from Chiang Mai province, which is an endemic area with intensity of 210–1,323. But, in this study, the study sites did not have any epidemic report, and the intensity seemed to be lower with the value 22–101 metacercariae per fish infected.

A high infection rate was found during both summer (April–May) and rainy (June–October) seasons, which decreased during the winter season (November–March). This result is similar to the study by Purivirojkul [

13], who reported that the heterophyid metacercaria from some areas in northeast Thailand has the highest infection during the rainy season in terms of both prevalence and mean intensity. In addition, Sithithaworn et al. [

14] reported the mean intensity of

Opisthorchis viverrini metacercariae in the eye-spot barb (

Hampala dispar) from Mahasarakham province. A high mean intensity of infection was found in the period from the rainy to winter season (August–January), whereas a low mean intensity of infection was found between the summer and rainy seasons (February–July). For the swamp barb (

Puntius leiacanthus), the high and low intensities of infection occurred during similar periods to those in the eye-spot barb. These results are similar to the findings of Faust and Nishigori [

15], who reported that rainfall may force fecal material, including parasite eggs, into natural water resources. Consequently, high populations of snails are exposed to these parasites. Most trematodes require approximately a 2-month developmental period from egg to metacercaria.

Four species of metacercariae of intestinal trematodes were detected in this study, including (1) S. falcatus, (2) Posthodiplostomum sp., (3) C. formosanus, and (4) Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. The ITS2 sequence data from these metacercariae were approximately 432, 394, 396, and 398 bp, respectively. The nucleotide comparison with BLASTn result and phylogenetic tree showed that the metacercariae in this study were related to S. falcatus, C. formosanus, P. centrarchi, and H. dubinini. The phylogenetic tree showed high relationships of our specimens with trematodes from the GenBank database. These trematodes have never been reported in Bangkok metropolitan region. Especially, C. formosanus and Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. have been first reported in the wrestling halfbeak. Stellantchasmus falcatus and C. formosanus are important minute intestinal flukes of humans.

Stellantchasmus falcatus metacercariae are among the most frequent and abundant parasites and were found in the muscles, abdominal cavity, and head. The infection rate of

S. falcatus in this study was 52.0% (51.6 metacercariae per fish infected). It was less than that of the wrestling halfbeak collected from Chiang Mai province [

4,

5]. The prevalence was 100% and 90%, while the mean intensity was 999.5 and 919 metacercariae per fish infected. However, this result is more than that of Saenphet et al. [

16] (39.3% of infection), and metacercariae were found in the body cavity and under the scales. In addition,

S. falcatus metacercariae were similar in size to

S. falcatus metacercariae (220×168 μm in average size) in mullet from Cambodia. Their prevalence and average intensity were 100% and 177 metacercariae per fish infected, respectively [

17]. In contrast, they were somewhat smaller than those from the mullet in Vietnam. The metacercariae were 297×232 μm in size and had a V-shaped excretory bladder [

18]. Many species of fish, including the wrestling halfbeak, garfish (

Xenentodon canciloides), mullet (

Mugil cephalus), mullet (

C. macrolepis), common carp (

Cyprinus carpio), and grass carp (

Ctenopharyngodon idella) have been reported to be the second intermediate hosts for

S. falcatus metacercariae in Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Korea, and Vietnam [

10,

17,

19,

20]. Recently, Wongsawad et al. [

7] reported that the metacercariae found in the wrestling halfbeak in Chiang Mai province was

S. dermogenysi n. sp., which was derived using molecular biology techniques with the mitochondrial cytochrome

c oxidase 1 gene. A phylogenetic tree suggests that

S. dermogenysi n. sp. is separated from

S. falcatus. It is a different gene from the one analyzed in this study, and it is difficult to analyze and compare these results together. Therefore, we tentatively assigned that the metacercariae found in the wrestling halfbeak were

S. falcatus, according to the previous studies of Chuboon and Wongsawad [

21], Sripalwit et al. [

3–

5] and Wongsawad et al. [

22,

23].

Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercariae were found only in the abdominal cavity and they were “neascus” metacercariae. They were nearly similar in size to

Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercariae from Chiang Mai province (720–880×660–830 μm in size) [

3]. The prevalence and mean intensity in this study were 65.8% and 23.1 metacercariae per fish infected, respectively. The infection rate of this result was more than that of the fish from Chiang Mai and Lamphun provinces. The prevalence was 1.2% and 3.4% [

3,

6]. On the contrary, Nguyen et al. [

24] reported high prevalence (100%) of

Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercariae in the trunk muscle of northern snakeheads (

Channa argus) from the Fushinogawa River, Yamaguchi, Japan. The second intermediate hosts of this fluke included several species of freshwater fish, such as the wrestling halfbeak in Thailand, northern snakeheads and Japanese medaka (

Oryzias latipes) in Japan [

25], and galaxiid fish (

Galaxias maculatus) in Argentina [

26]. Furthermore, molecular analysis showed that

Posthodiplostomum sp. was similar to

P. centrarchi. Interestingly, Stoyanov et al. [

27] found

P. centrarchi metacercariae in pumpkinseed sunfish (

Lepomis gibbosus) from the Lake Atanasovsko, Bulgaria, in the liver, body cavity and mesenteries, similar to our results.

Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. metacercariae were “prohemistomulum” metacercariae. They were found only in the muscle. The characteristic organ of the family Cyathocotylidae, the holdfast organ is located within the ventral concavity [

12]. The BLAST search results showed the closest similarity of cyathocotylid metacercariae found in wrestling halfbeak to

H. dubinini, but the similarity was relatively low (similarity ~86%). In this study, Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. metacercariae were different in size and shape from those of

Holostephanus metorchis (164×140 μm in average size) from a fish,

Pseudorasbora parva, found in the Republic of Korea, and the cyst wall was thinner than that of

H. metorchis [

28]. Previous studies reported that the roach (

Rutilus rutilus) found in the Gulf of Finland is considered a second intermediate host of

H. dubinini [

29].

Centrocestus formosanus was found only in the gill filaments. The prevalence and mean intensity were 1.2% and 3.2 metacercariae per fish infected, respectively. In this study, it has been confirmed for the first time that the wrestling halfbeak plays the role of a second intermediate host of

C. formosanus in Thailand. Normally,

Centrocestus sp. metacercariae have been highly infected on the gills of several freshwater fish, including the climbing perch (

Anabas testudineus), flying barb (

Esomus metallicus), golden little barb (

Puntius brevis), longfin mojarra (

Parambassis siamensis), crucian carp (

Carassius auratus), or ornamental fish, such as zebrafish (

Danio rerio) and tiger barb (

Puntigrus tetrazona) [

30–

32]. The size from this result is different from that of

C. formosanus metacercariae in the golden little barb from Vientiane Municipality in Laos. They were elliptical, 178×143 μm in size, and yellowish brown, and the mean intensity was 11.7 metacercariae per fish infected [

33].

Conclusively, it has been confirmed that the wrestling halfbeak from Bangkok metropolitan region plays the role of the second intermediate host and is moderately infected by 4 genera of metacercariae. The results showed that S. falcatus and Posthodiplostomum sp. are the most common species found in the wrestling halfbeak. In addition, this is the first report of C. formosanus and Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. in the wrestling halfbeak, and Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. is first reported as a fish parasite in Thailand. So, the results would be useful as basic data for the management of freshwater fish resource in the future. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the population in Bangkok metropolitan region is at risk for parasitic infections with zoonotic intestinal trematodes.

Notes

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Development and Promotion of Science and Technology Talents Project, Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI), Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University (International SciKU Branding, ISB) and Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand. We also thank the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand, and The Korea Association of Health Promotion, Seoul, the Republic of Korea. Thanks are due to the team of researchers who provided useful materials for this overview. This research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Thailand under project number ACKU61-SCI-036.

Fig. 1Study area with 78 sampling sites in Bangkok metropolitan region.

Fig. 2Metacercariae collected from wrestling halfbeak fish in Bangkok metropolitan region. (A, B) S. falcatus metacercaria; elliptical with thick wall and 212×188 μm in average size, having yellowish-brown pigment granules, body covered with scale-like spines, oral sucker (OS) subterminal, pharynx (P) elongate-oval, prepharynx almost absent, ventral sucker (VS) smaller than oral sucker, a thick-walled expulser (E), and an excretory bladder (EB) with dark granules. (C) S. falcatus metacercaria; round and 237×223 μm in average size, and a pair of eyespots (ES). (D) Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. metacercaria; prohemistomulum metacercaria with thin wall, round and 313×300 μm in average size, pharynx elongate-oval, and a holdfast organ (HO) visible. (E) Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercaria; large neascus metacercariae, elliptical with thin wall, and 816×499 μm in average size, body distinctly bipartite (forebody and hindbody), forebody larger than hindbody, oval to lanceolate, with ventral concavity, covered with numerous tiny spines, hindbody bulb-shaped or oval, without spines, oral sucker terminal, pharynx elongate-oval, holdfast organ well-developed, round or oval in shape, located near the constriction at the posterior part of forebody, and copulatory bursa (CB) visible, terminal or slightly dorsal. (F) C. formosanus metacercaria; elliptical and 261×182 μm in average size, body covered with scale-like spines, an X-shaped excretory bladder with dark granules, oral sucker terminal with circumoral spines in 2 rows, ventral sucker smaller than oral sucker, and pharynx elongate-oval. All scale bars are 100 μm.

Fig. 3Phylogenetic trees of partial ITS2 sequences. (A) A phylogenetic tree drawn by neighbor-joining method. (B) Another phylogenetic tree drawn by maximum-likelihood method. Bootstrap values were computed independently for 10,000 resembling.

Table 1Infection status of the wrestling halfbeak from Bangkok metropolitan region of Thailand

Table 1

|

Surveyed area |

No. of fish examined |

No. (%) of fish infected |

No. of DTM detected |

|

Total |

Range |

Average |

|

Bangkok |

858 |

654 (76.2) |

34,838 |

1–584 |

53.3 |

|

Nakhon Pathom |

539 |

421 (78.1) |

9,813 |

1–339 |

23.3 |

|

Nonthaburi |

1,122 |

958 (85.4) |

21,295 |

1–495 |

22.2 |

|

Pathum Thani |

644 |

578 (89.8) |

21,376 |

1–490 |

37.0 |

|

Samut Prakan |

986 |

944 (95.7) |

94,897 |

1–941 |

100.5 |

|

Samut Sakhon |

352 |

319 (90.6) |

7,317 |

1–352 |

22.9 |

|

Total |

4,501 |

3,874 (86.1) |

189,536 |

|

48.9 |

Table 2Infection status of the wrestling halfbeak with each species of metacercariae in Bangkok metropolitan region, Thailand

Table 2

|

Species of DTM |

No. of fish examined |

No. (%) of fish infected |

No. of metacercarial |

|

Total |

Range |

Average |

|

Stellantchasmus falcatus

|

4,501 |

2,341(52.0) |

120,777 |

1–941 |

51.6 |

|

Posthodiplostomum sp. |

4,501 |

2,960 (65.8) |

68,450 |

1–495 |

23.1 |

|

Cyathocotylidae fam. sp. |

4,501 |

96 (2.1) |

135 |

1–3 |

1.4 |

|

Centrocestus formosanus

|

4,501 |

54 (1.2) |

174 |

1–5 |

3.2 |

Table 3Seasenal infection status of the wrestling halfbeak with each species of metacercariae in Bangkok metropolitan region in Thailand

Table 3

|

Season surveyed |

No. of fish examined |

No. (%) of fish infected |

No. of metacercarial |

|

Total |

Range |

Average |

|

Winter |

1,020 |

826 (81.0) |

32,110 |

1–584 |

38.9 |

|

Summer |

1,430 |

1,255 (87.8) |

58,438 |

1–391 |

46.6 |

|

Rainy |

2,051 |

1,793 (87.4) |

98,988 |

1–941 |

55.2 |

References

- 1. Radomyos B, Wongsaroj T, Wilairatana P, Radomyos P, Praevanich R, Meesomboon V, Jongsuksuntikul P. Opisthorchiasis and intestinal fluke infection in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1998;29:123-127.

- 2. Fan PC. Viability of metacercariae of Clonorchis sinensis in frozen or salted freshwater fish. Int J Parasitol 1998;28:603-605.

- 3. Sukontason K, Wongsawad C, Anuntalabhochai S, Wongsawad P. Molecular Genotyping and Geographic Distribution of Heterophyid Trematodes in upper Part of Ping River Basin. Bangkok, Thailand. Research Reports of Science and Technology Research Institute, Chiang Mai University; 2012, (in Thai)..

- 4. Sripalwit P, Wongsawad C, Chai JY, Anuntalabhochai S, Rojanapaibul A. Investigation of Stellantchasmus falcatus metacercariae in half-beaked fish, Dermogenus pusillus from four districts of Chiang Mai province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2003;34:281-285.

- 5. Sripalwit P, Wongsawad C, Chontananarth T, Anuntalabhochai S, Wongsawad P, Chai JY. Developmental and phylogenetic characteristics of Stellantchasmus falcatus (Trematoda: Heterophyidae) from Thailand. Korean J Parasitol 2015;53:201-207.

- 6. Wongsawad C, Rojanapaibul A, Mhad-arehin N, Pachanawan A, Marayong T, Suwattanacoupt S, Rojtinnakorn J, Wongsawad P, Kumchoo K, Nichapu A. Metacercaria from freshwater fishes of Mae Sa stream, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2000;31(suppl):54-57.

- 7. Wongsawad C, Nantarat N, Wongsawad P, Butboonchoo P, Chai JY. Morphological and molecular identification of Stellantchasmus dermogenysi n. sp. (Digenea: Heterophyidae) in Thailand. Korean J Parasitol 2019;57:257-264.

- 8. Chanawong A, Waikagul J, Thammapalerd N. Detection of shared antigens of human liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini and its snail host, Bithynia spp. Trop Med Parasitol 1990;41:419-421.

- 9. Saxton TM, Fried B, Peoples RC. Excystation of the encysted metacercariae of Echinostoma trivolvis and Echinostoma caproni in a trypsin-bile salts-cysteine medium and morphometric analysis of the excysted larvae. J Parasitol 2008;94:669-671.

- 10. Chai JY, Sohn WM, Na BK, Park JB, Jeoung HG, Hoang EH, Htoon TT, Tin HH. Zoonotic trematode metacercariae in fish from Yangon, Myanmar and their adults recovered from experimental animals. Korean J Parasitol 2017;55:631-641.

- 11. Sohn WM. Fish-borne Zoonotic trematode metacercariae in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2009;47:103-113.

- 12. Gibson DI, Jones A, Bray RA. Key to the Trematoda. 1:1st ed.. New York, USA. CABI publishing; 2002, pp 167-212.

- 13. Purivirojkul W. Survey of fish species infected with trematode metacercariae from some areas in northeast Thailand. J Fish Tech Res 2011;5:75-86.

- 14. Sithithaworn P, Pipitgool V, Srisawangwong T, Elkins DB, Haswell-Elkins MR. Seasonal variation of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in cyprinoid fish in north-east Thailand: implications for parasite control and food safety. Bull World Health Organ 1997;75:125-131.

- 15. Faust EC, Nishigori M. The life cycles of two new species of heterophyidae, parasitic in mammals and bird. J Parasitol 1926;13:91-132.

- 16. Saenphet S, Wongsawad C, Saenphet K. A survey of helminths in freshwater animals from some areas in Chiang Mai. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2001;32:210-213.

- 17. Chai JY, Sohn WM, Na BK, Jeoung HG, Sinuon M, Socheat D.

Stellantchasmus falcatus (Digenea: Heterophyidae) in Cambodia: discovery of metacercariae in mullets and recovery of adult flukes in an experimental hamster. Korean J Parasitol 2016;54:537-541.

- 18. Chai JY, De NV, Sohn WM. Foodborne trematode metacercariae in fish from northern Vietnam and their adults recovered from experimental hamsters. Korean J Parasitol 2012;50:317-325.

- 19. Ditrich O, Scholz T, Giboda M. Occurrence of some medically important flukes (Trematoda: Opisthorchiidae and Heterophyidae) in Nam Ngum water reservoir, Laos. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1990;21:482-488.

- 20. Chi TT, Dalsgaard A, Turnbull JF, Tuan PA, Murrell KD. Prevalence of zoonotic trematodes in fish from a Vietnamese fish-farming community. J Parasitol 2008;94:423-428.

- 21. Chuboon S, Wongsawad C. Molecular identification of larval trematode in intermediate hosts from Chiang Mai, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2009;40:1216-1220.

- 22. Wongsawad C, Nantarat N, Wongsawad P. Phylogenetic analysis reveals cryptic species diversity within minute intestinal fluke, Stellantchasmus falcatus Onji and Nishio, 1916 (Trematoda, Heterophyidae). Asian Pac J Trop Med 2017;10:165-170.

- 23. Wongsawad C, Chariyahpongpun P, Namue C. Experimental host of Stellantchasmus falcatus

. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1998;29:406-409.

- 24. Nguyen TC, Li YC, Makouloutou P, Jimenez LA, Sato H.

Posthodiplostomum sp. metacercariae in the trunk muscle of northern snakeheads (Channa argus) from the Fushinogawa river, Yamaguchi, Japan. J Vet Med Sci 2012;74:1367-1372.

- 25. Toyooka R, Okada K. Studies on the development of two diplostomatid metacercariae, found in Oryzias latipes, a freshwater fish. J Gakugei Tokushima Univ 1954;4:55-64.

- 26. Ritossa L, Flores V, Viozzi G. Life-cycle stages of a Posthodiplostomum species (Digenea: Diplostomidae) from Patagonia, Argentina. J Parasitol 2013;99:777-780.

- 27. Stoyanov B, Georgieva S, Pankov P, Kudlai O, Kostadinova A, Georgiev BB. Morphology and molecules reveal the alien Posthodiplostomum centrarchi Hoffman, 1958 as the third species of Posthodiplostomum Dubois, 1936 (Digenea: Diplostomidae) in Europe. Syst Parasitol 2017;94:1-20.

- 28. Seo M, Guk SM, Chai JY, Sim S, Sohn WM.

Holostephanus metorchis (Digenea: Cyathocotylidae) from chicks experimentally infected with metacercariae from a fish, Pseudorasbora parva, in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2008;46:83-86.

- 29. Näreaho A, Eriksson-Kallio AM, Heikkinen P, Snellman A, Sukura A, Koski P. High prevalence of zoonotic trematodes in roach (Rutilus rutilus) in the Gulf of Finland. Acta Vet Scand 2017;59:75.

- 30. Wongsawad C, Wongsawad P, Sukontason K, Maneepitaksanti W, Nantarat N. Molecular phylogenetics of Centrocestus formosanus (Digenea: Heterophyidae) originated from freshwater fish from Chiang Mai province, Thailand. Korean J Parasitol 2017;55:31-37.

- 31. Noikong W, Wongsawad C, Phalee A. Seasonal variation of metacercariae in cyprinoid fish from Kwae Noi Bamroongdan Dam, Phitsanulok province, northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2011;42:58-62.

- 32. Wanlop A, Wongsawad C, Prattapong P, Wongsawad P, Chontananarth T, Chai JY. Prevalence of Centrocestus formosanus metacercariae in ornamental fish from Chiang Mai, Thailand, with molecular approach using ITS2. Korean J Parasitol 2017;55:445-449.

- 33. Han ET, Shin EH, Phommakorn S, Sengvilaykham B, Kim JL, Rim HJ, Chai JY.

Centrocestus formosanus (Digenea: Heterophyidae) encysted in the freshwater fish, Puntius brevis, from Lao PDR. Korean J Parasitol 2008;46:49-53.