INTRODUCTION

Paragonimiasis occurs globally, but is one of the important enzootic helminthic diseases endemic to East and southeast Asian countries. The red-brown colored lung fluke infects humans and mammals, and thrives mainly in the host lung, forming granulomatous cysts.

Paragonimus spp. infect the host for more than 20 years. It can sometimes ectopically migrate to any part of the body. Its most common extrapulmonary site is the subcutaneous tissue followed by abdominal cavity, liver, and brain. Cerebral paragonimiasis is one of the most important extrapulmonary forms with serious consequences and high mortality compared to the pulmonary form [

1–

4]. Paragonimiasis is diagnosed by the combination of sputum examination, serological tests, and imaging studies. In the case of cerebral paragonimiasis, brain magnetic resonance (MR) or computed tomography (CT) images help confirm various cystic and nodular space-occupying lesions. Most of cerebral cases are associated with chronic morbidity due to epilepsy, dementia and various neurologic sequelae [

5]. Kim et al. [

6] has also divided the various presentations of cerebral diseases into those with meningitis forms, mass lesions, dementia, epilepsy, etc.

There have been relatively few case reports of dementia associated with cerebral paragonimiasis, although it is known that dementic change may be an important aspect of the disease. Clinical features of cerebral paragonimiasis are comparable to those caused by neurocysticercosis, as manifested by several dementia cases [

7,

8]. We report a case of chronic cerebral paragonimiasis presenting with dementia to extend understanding of dementia related to cerebral paragonimiasis.

CASE RECORD

An 80-year-old Korean male reported memory and cognitive disorders without any disturbance in consciousness and alertness in his daily life for the last 3 years. He had not received any treatment, but was suspected of having had memory and cognitive deterioration in a dementia screening inspection at a public health center. He was transferred to the Psychiatry Department of our hospital. He was a retired farmer with a 6th-grade education. At age of 19, he visited a hospital with the chief complaints of aggravating headaches and was diagnosed with meningitis. His symptoms improved with drug therapy. One year later, he was drafted into the army. Three months later after he began his service in the seashore of Jeju Island, Korea, he was discharged due to fever, chills, abdominal pain and hemoptysis. Since then, he had experienced generalized tonic clonic (GTC) seizure once a month for 25 years. He took medicine for 3 months but voluntarily stopped. Epileptic seizures continued once a month until he visited our hospital. The results of his general physical and systemic examination were within normal ranges. There was no focal neurological deficit, and his cranial nerves were intact.

The results of the Consortium to Establish A Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD-K; Korean version) test conducted when the subject visited the Psychiatry Department of our hospital were as follows: 7 marks for the Word Fluency Test (↓), 4 for the Boston Naming Test (↓↓), 14 for the Korean version of MMSE in the Korean version of CERAD Assessment Packet (MMSE-KC) (↓↓), 1 for the Word List Recall Test (↓↓), 5 for the Word List Recognition Test (↓↓), and 245 seconds for the Trail Making A (↓↓). The patient was assessed as suffering from dementia with 4 marks on the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) and 1 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDRS). He also had a mild depression with 15/30 marks on the Geriatric Depression Scale.

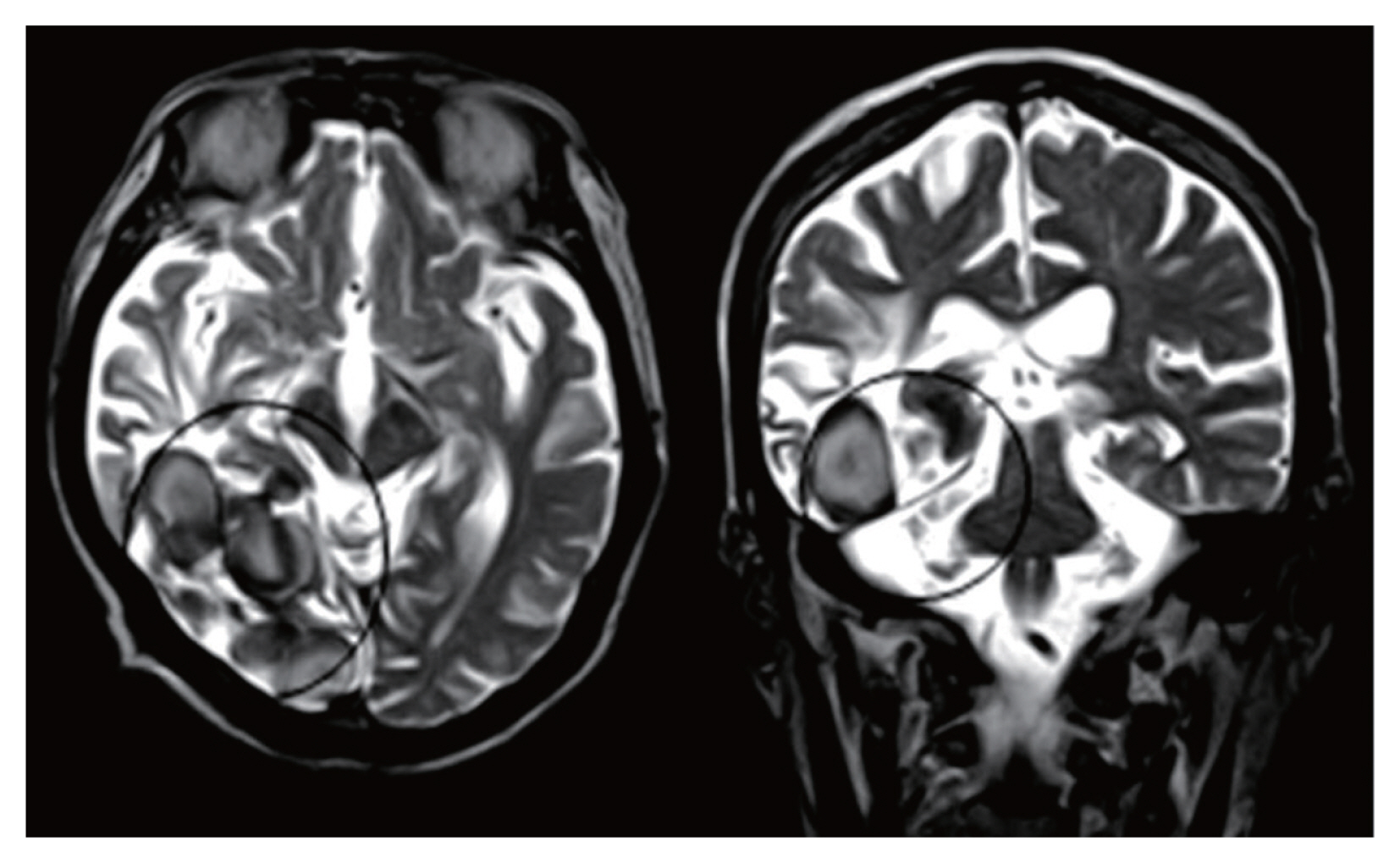

The neurological tests showed that the patient’s consciousness was clear. There were no findings of muscular anomalies. Motor and sensory functions were within normal range. However, the contrast-enhanced brain MRI revealed encephalomalacia in the right occipital and temporal lobes. Calcification and cystic lesions mainly in the right occipital lobe were also noticed (

Fig. 1). As the patient was suspected of having paragonimiasis or cysticercosis, specific IgG antibody levels against

Paragonimus westermani and

Taenia solium metacestode were measured in his serum sample by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA results showed that the patient had anti-

Paragonimus specific IgG antibody levels of 2.49 (positive criterion: 0.25), and those against anti-T. solium metacestode were 0.26 (positive criterion: 0.18). There was no abnormal in the chest X-ray images.

DISCUSSION

Our patient had a history of fever, chills, abdominal pain, and hemoptysis during 3 months of military service. He might be infected with paragonimiasis at that time. However, he could not receive adquate management because no effective agents for treating paragonimiasis had been developed until the early 1960s.

Previous studies have reported brain involvement of 2–27% of paragonimiasis patients and 30.3–60.4% of patients with extrapulmonary paragonimiasis cases [

9–

14]. Due to the space-occupying lesion in the brain, localizing neurologic signs might be observed. In this study, we expected to find some lesions in the lungs because anti-Paragonimus specific IgG antibody titers exceptionally high (2.49), but we found lesions only in the brain.

The most common symptoms of cerebral paragonimiasis include visual impairment, mental deterioration, headache, hemiplegia, nausea, and vomiting [

12–

15]. Marty and Neafie reported that approximately 70% of cerebral paragonimiasis patients presented personality changes and a decline of cognitive function [

16]. In some cases, however, these symptoms developed 30 years after the patient became infected [

12]. In our case, the patient experienced GTC seizures once a month for 35 years since his first symptom appeared, which were accompanied by memory loss and cognitive declination. Considering the possibility of developing dementia in cerebral paragonimiasis patients [

17,

18], we surmise that our patient may have experienced cognitive deterioration due to cerebral paragonimiasis.

In general, Alzheimer’s disease dementia shows moderate to severe atrophy of medial temporal lobe. However, this patient did not show prominent brain atrophy compared to those with similar ages, suggesting that the etiology of the patient’s dementia symptom might be more related to chronic cerebral paragonimiasis. This case showed that cerebral paragonimiasis of the right temporo-occipital areas could induce the dementia.

Notes

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Fig. 1Horizontal (left) and coronal view (right) of brain MR image of an 80-year-old man who presented with dementia. Complicated cystic structures and calcifications (circles) are seen mainly in the right occipital lobe, with encephalomalasias in the right occipital and temporal lobes.

References

- 1. Im JG, Chang KH, Reeder MM. Current diagnostic imaging of pulmonary and cerebral paragonimiasis, with pathological correlation. Semin Roentgenol 1997;32:301-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0037-198x(97)80024-7

- 2. Chen Z, Zhu G, Lin J, Feng H. Acute cerebral paragonimiasis presenting as hemorrhagic stroke in a child. Pediatr Neurol 2008;39:133-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.04.004

- 3. Kohli S, Farooq O, Jani RB, Wolfe GI. Cerebral paragonimiasis: an unusual manifestation of a rare parasitic infection. Pediatr Neurol 2015;52:366-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.11.001

- 4. Amaro DE, Cowell A, Tuohy MJ, Procop GW, Morhaime J, Reed SL. Cerebral paragonimiasis presenting with sudden death. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;95:1424-1427. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0902

- 5. Singh TS, Khamo V, Sugiyama H. Cerebral paragonimiasis mimicking tuberculoma: first case report in India. Trop Parasitol 2011;1:39-41. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.72106

- 6. Kim JG, Ahn CS, Kang I, Shin JW, Jeong HB, Nawa W, Kong Y. Cerebral paragonimiasis: Clinicoradiological features and serodiagnosis using recombinant yolk ferritin. Plos Negl Trp Dis 2022;16:e0010240.

- 7. Jha S, Ansari MK. Dementia as the presenting manifestation of neurocysticercosis: a report of two patients. Neurol Asia 2010;15:83-87.

- 8. Ramirez-Bermudez JHJ, Sosa AL, Lopez-Meza E, Lopez-Gomez M, Corona T. Is dementia reversible in patients with neurocysticercosis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:1164-1166. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2004.052126

- 9. Theresia G, Hans-W G, Shin SW. Pulmonary and extrapulmonary paragonimiasis in 311 cases studies in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis 1957;4:117-131.

- 10. Hawn TR, Jong EC. Update on hepatobiliary and pulmonary flukes. Curr Infect Dis Rep 1999;1:427-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-999-0054-y

- 11. Miyazaki I. Cerebral paragonimiasis. Contemp Neurol Ser 1975;12:109-132.

- 12. Xia Y, Chen J, Ju Y, You C. Characteristic CT and MR imaging findings of cerebral paragonimiasis. J Neuroradiol 2016;43:200-206.

- 13. Toyonaga S, Mori K, Suzuki N. Cerebral paragonimiasis-report of five cases. Neurol Med Chir 1992;32:157-162. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.32.157

- 14. Kang SY, Kim TK, Kim TY, Ha YI, Choi SW, Hong SJ. A case of chronic cerebral paragonimiasis westermani. Korean J Parasitol 2000;38:167-171. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2000.38.3.167

- 15. Udaka F, Okuda B, Tsuji T, Kameyama M. CT findings of cerebral paragonimiasis in the chronic state. Neuroradiology 1988;30:31-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00341939

- 16. Marty AM, Neafie RC. Paragonimiasis. In Myers WM, Neafie RC, Marty AM, Wear DJ eds, Pathology of Infectious Diseases, vol I. Helminthiases. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington DC, USA. 2000, pp 49-67.

- 17. Kusner DJ, King CH. Cerebral paragonimiasis. Semin Neurol 1993;13:201-208. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1041126

- 18. Oh SJ. Paragonimus meningitis. J Neurol Sci 1968;6:419-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510x(68)90028-2

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A comprehensive review on the neurological impact of parasitic infections

Firooz Shahrivar, Ata Moghimi, Ramin Hosseinzadeh, Mohammad Hasan Kohansal, Ali Mortazavi, Tahereh Mikaeili Galeh, Ehsan Ahmadpour

Microbial Pathogenesis.2025; 206: 107762. CrossRef - Answer to April 2024 Photo Quiz

Alfredo Maldonado-Barrueco, Sol María San José-Villar, Julio García-Rodríguez, Marina Alguacil-Guillén, Álvaro López-Janeiro, Elena Trigo-Esteban, Marta Díaz-Menéndez, Guillermo Ruiz-Carrascoso, Bobbi S. Pritt

Journal of Clinical Microbiology.2024;[Epub] CrossRef