Abstract

Dipylidium caninum is a cosmopolitan parasite of companion animals such as dogs and cats. Accidental infection in humans occur mostly in children. Although considerable number of cases were reported from Europe and the Americas, case reports of this zoonotic disease are rather scarce from Asian countries. The aim of this study is to report the results of literature survey on dipylidiasis cases in humans in Japan. Conclusively, we have found a total of 17 cases since the first case report in from Aichi Prefecture in 1925.

-

Key words: Dipylidium caninum, humans, Japan

Introduction

Dipylidiasis is a zoonotic helminthiasis caused by infection with a tapeworm,

Dipylidium caninum, of which definitive hosts are canines and felines. Human infection occurs when plerocercoids (infective stage larvae) in dog or cat fleas or chewing lice are accidentally ingested by humans. Infection in humans is, thus, mostly seen in children, especially infants of <6 months old who have a chance of close contact with pet animals [

1]. Recently, Rousseau et al. [

2] made a complehensive literature survey on dipylidiasis in companion animals and humans during the last 21 years (2000–2021), and clearly demonstrated that, even nowadays, dipylidiasis is globally seen in companion animals with sporadic accidental infection in humans, mostly in children. In their review, however, nothing was mentioned about epidemiological survey or case reports in Japan. On the other hand, Jiang et al. [

3] mentioned in their case report and literature survey on dipylidiasis, there are 30 cases in China and 81 cases in Japan. To solve the discrepancy of human dipylidiasis in Japan by Rousseau et al. [

2] and Jiang et al. [

3], we have made a comprehensive literature review on dipylidiasis in Japan.

In Japan, the first case was reported in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture [

4]. Kagei [

5] made a first systematic review on human dipylidiasis in Japan with the list of 11 cases. Then, Ando [

6] added 3 more cases including their own case in Mie Prefecture. However, no such review has been made since then. Thus, we have made an extensive literature survey from 1990 till now using PubMed and Google Scholar, and also Japana centra revuo medicina (“Igaku Chuo Zasshi [ICHUSHI]”). The citations in each case report were carefully checked as well. Here we report the results of our literature survey on human dipylidiasis cases in Japan to update our knowledge on this neglected zoonoses in this country.

Dipylidiasis cases in Japan–the results of the literature survey

As mentioned as above, the first case of human dipylidiasis in Japan was reported by Tamura in 1925 [

4], and Kagei [

5] listed up a total of 11 sporadic cases in this country, and Ando (1995) [

6] added 3 more cases. After literature survey, we have found 2 more case reports since Ando’s review [

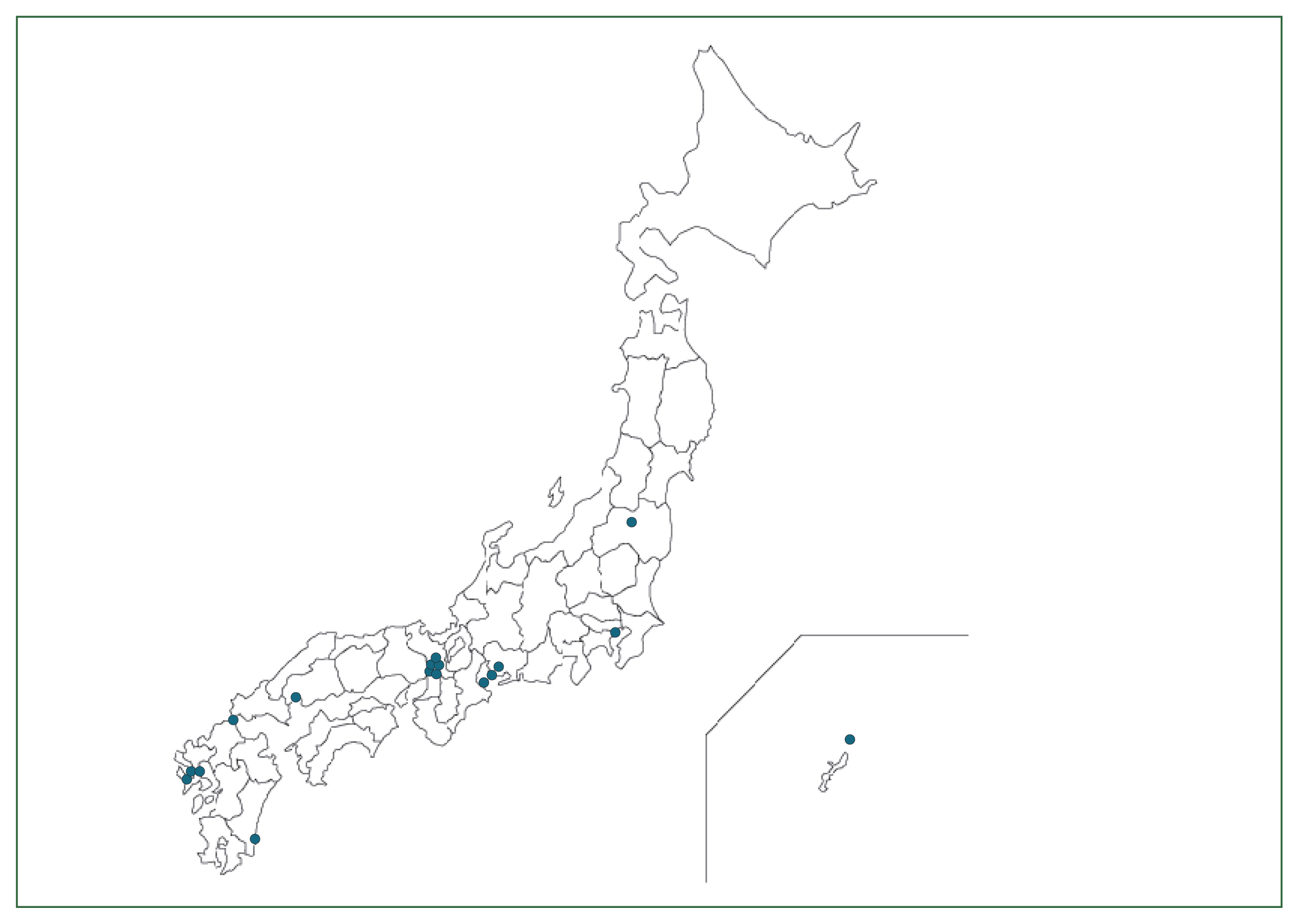

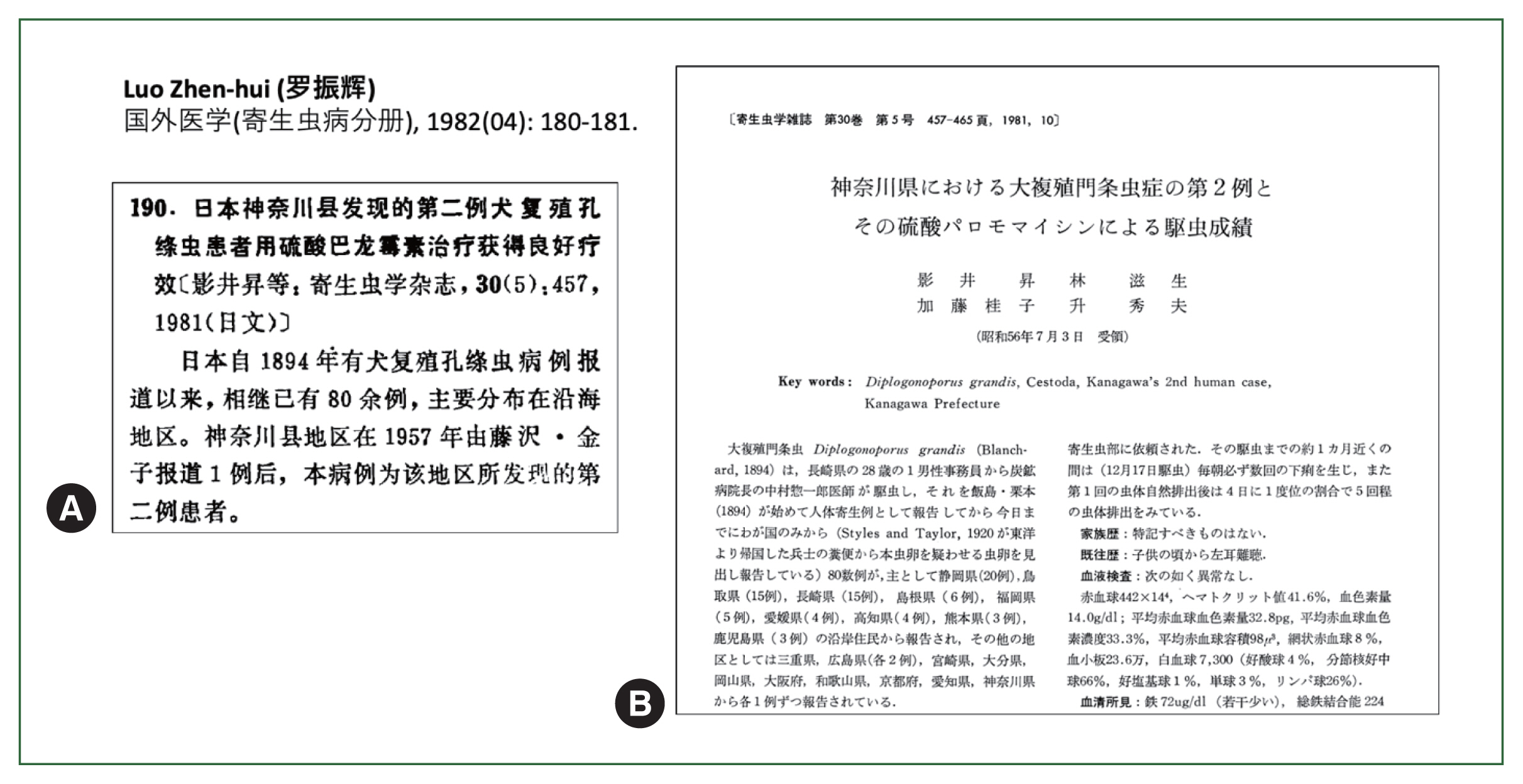

6]. In addition, in May 2021, a suspected case of dipylidiasis in a child was consulted from the attending pediatrician (AF in the authors) to the web-consultation system of the Japanese Society of Parasitology about a possible self-cure of dipylidiasis, alternative examination methods, efficacy, necessity/efficacy of praziquantel, etc. The patient was a 3 years-old boy in Yamaguchi Prefecture whose mother recognized rice-grain-like moving creatures in his stool in the nappy (

Fig. 1) occasionally for about 2 weeks. The mother mentioned that those creatures were apparently the same as those seen in the feces of their family cat which was under treatment for dipylidiasis. Although the patient was referred to the OPD of a regional central hospital for work-up of dipylidiasis, repeated copro-parasitological examination for dipylidiasis or other intestinal worms was negative even after administration of a gentle purgative. According to the advices from the web-consultant of JSP, the attending physician informed watchful waiting to the patient and his mother.

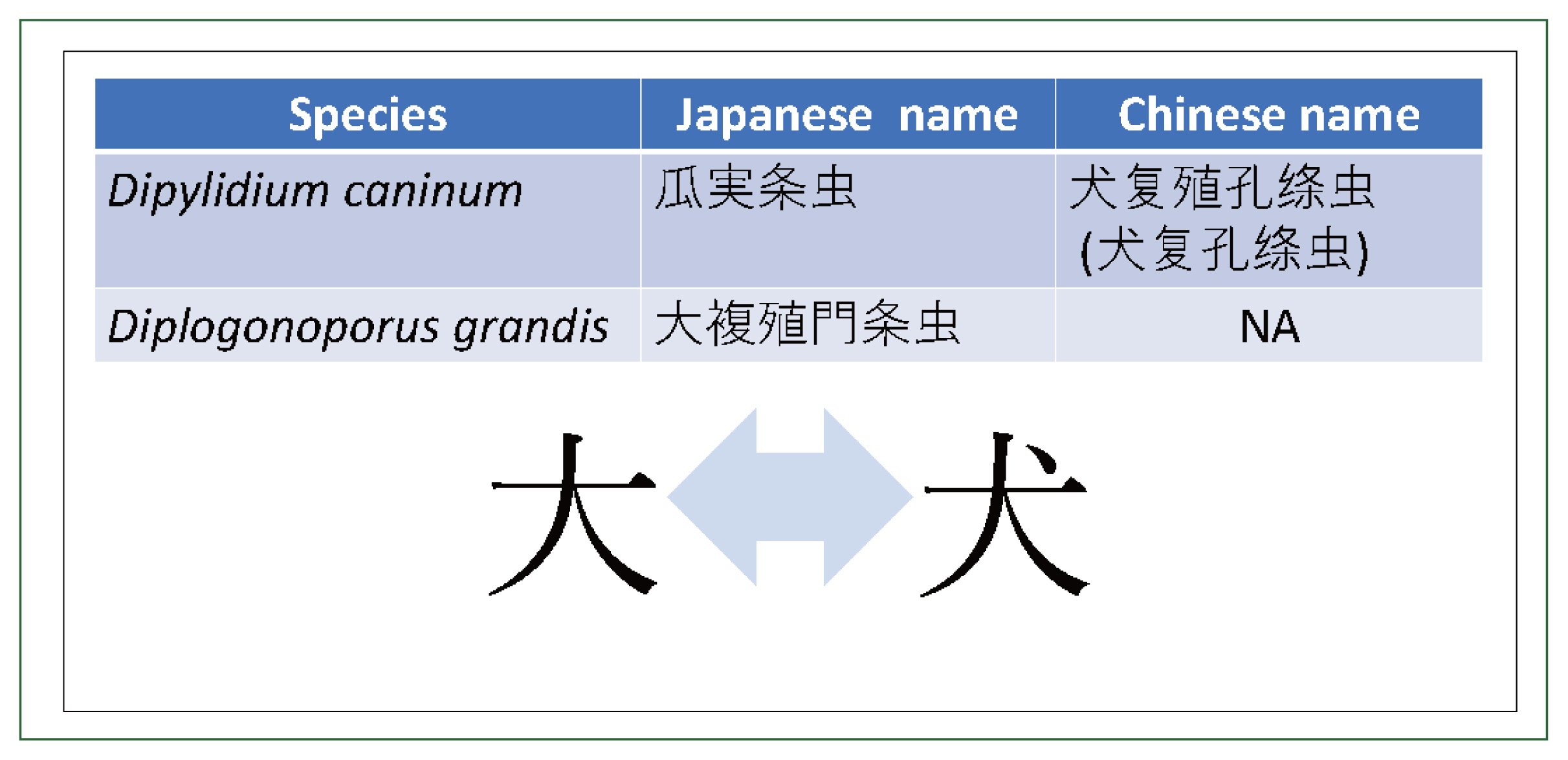

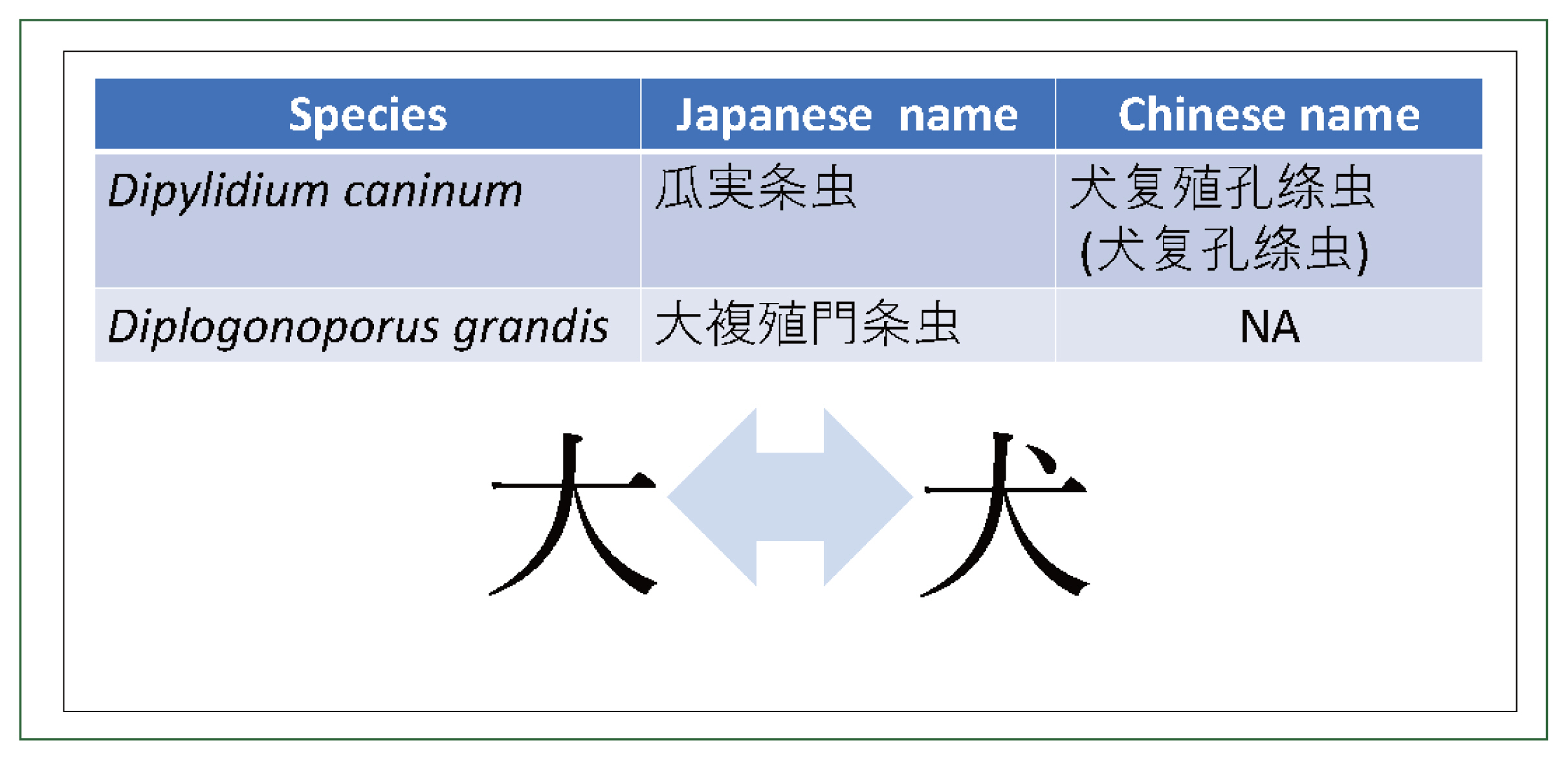

Thus, a total number of cumulated dipylidiasis cases in Japan up to now is 17 including the recent suspected case described above. Details of those 17 cases are summarized in

Table 1 [

4,

7–

27]. The patients are 6 males and 11 females and almost all of them are children of under 3 years old. Seven cases (41.1%) were below 1 year old. One case was a 58 years old woman who has a co-infection with hookworms [

12]. In terms of geographical distribution, most of the cases, except for one case each from Fukushima and Tokyo, were reported from central to southwestern part of Japan (

Fig. 2).

Discussion

In Japan, dipylidiasis still exists among companion dogs, although the infection rate is extremely low, less than 2% [

28,

29]. Accordingly, human dipylidiasis cases are still occasionally and sporadically found in Japan. This tendency as well as the clinical features of dipylidiasis in Japan are essentially the same as those seen in all over the world [

1]. Recently, Jiang et al. [

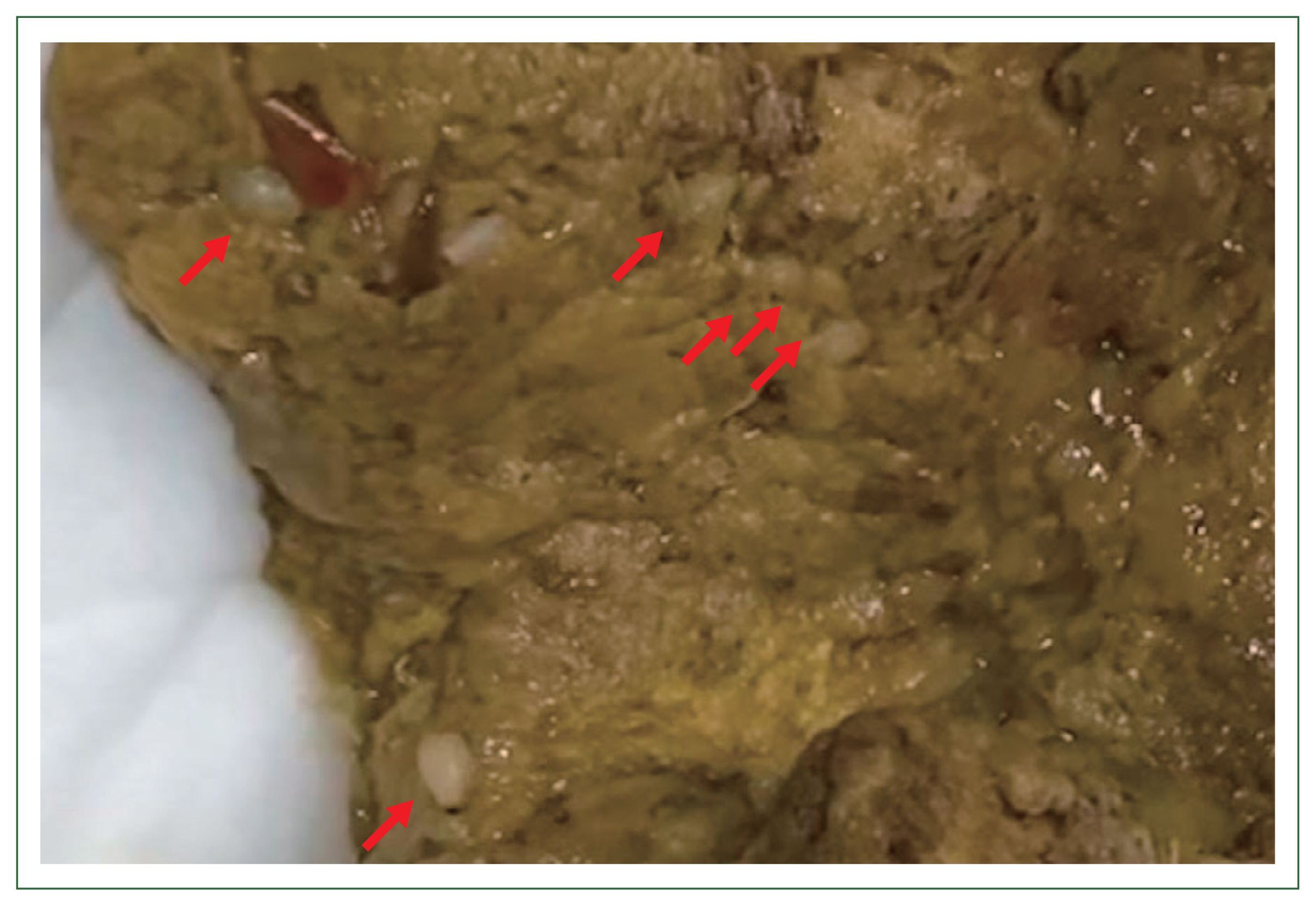

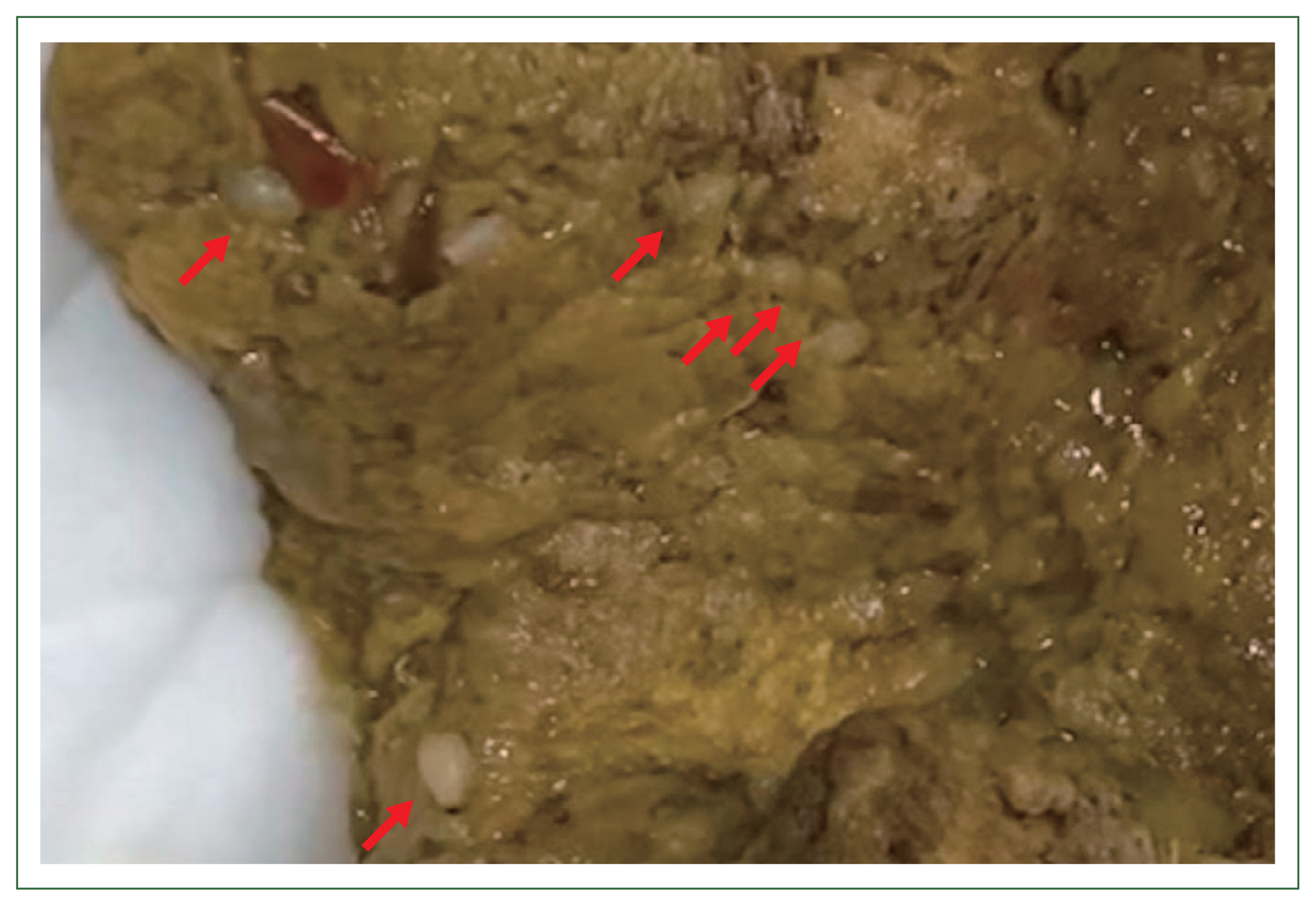

3] reported from China a case of dipylidiasis with a literature review. In their literature survey, they mentioned there are 349 cases from at least 24 countries until July 17, 2016, including 30 cases in China and 81 cases in Japan. Because the number of cases in Japan in their study and our present results were markedly different and their review did not have references/citations, one of us (YN) asked Dr. Jiang via email to share references related to dipylidiasis cases in Japan. Dr. Jiang kindly provided us a copy of the reference of Luo [

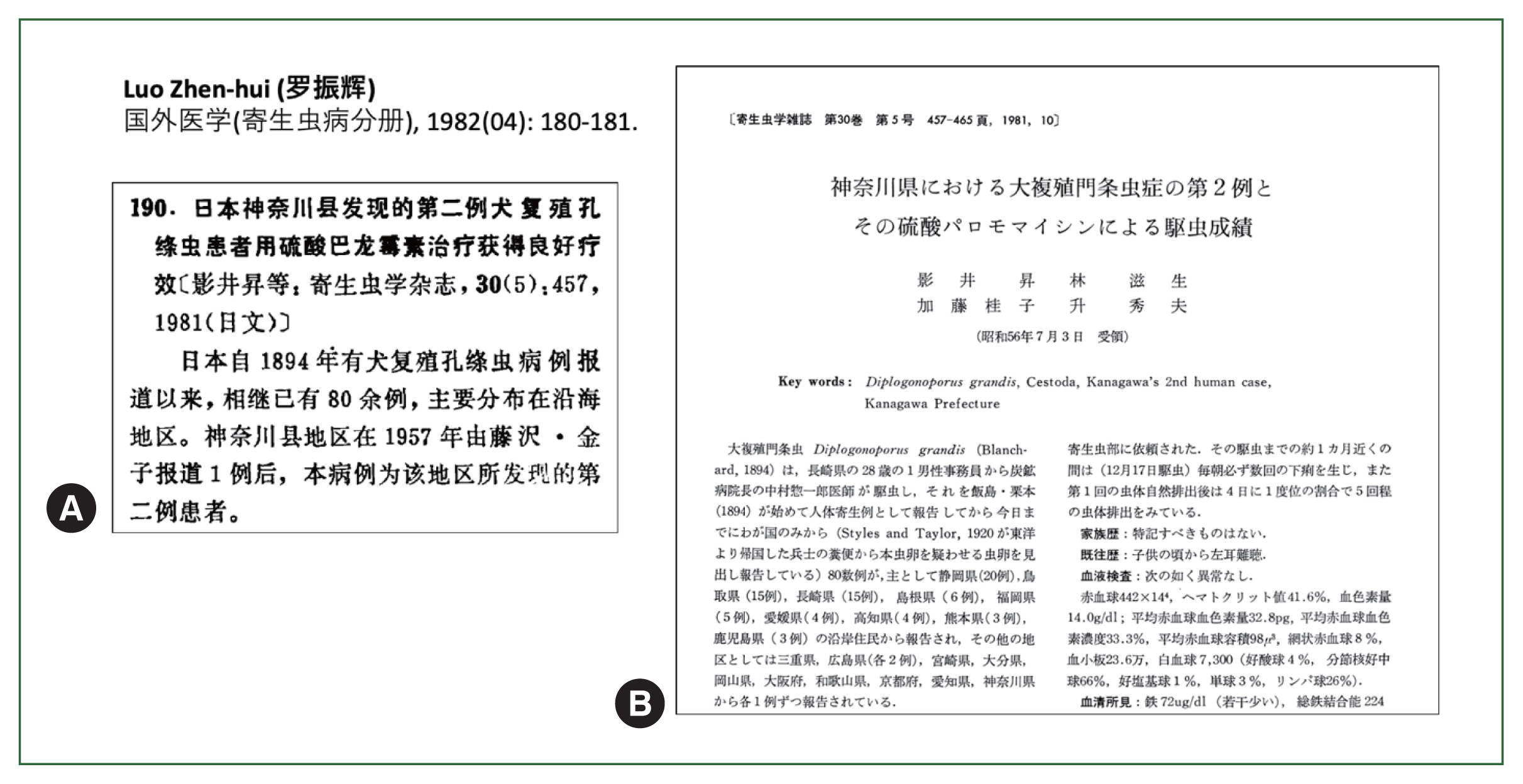

30], which was a Chinese-translated digest (

Fig. 3A) of the case report and a review by Kagei et al. [

31] (in Japanese) of the 2nd cases of

Diplogonoporus glandis infection in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, with the literature review of >80 cases of

D. glandis infection from all over Japan (

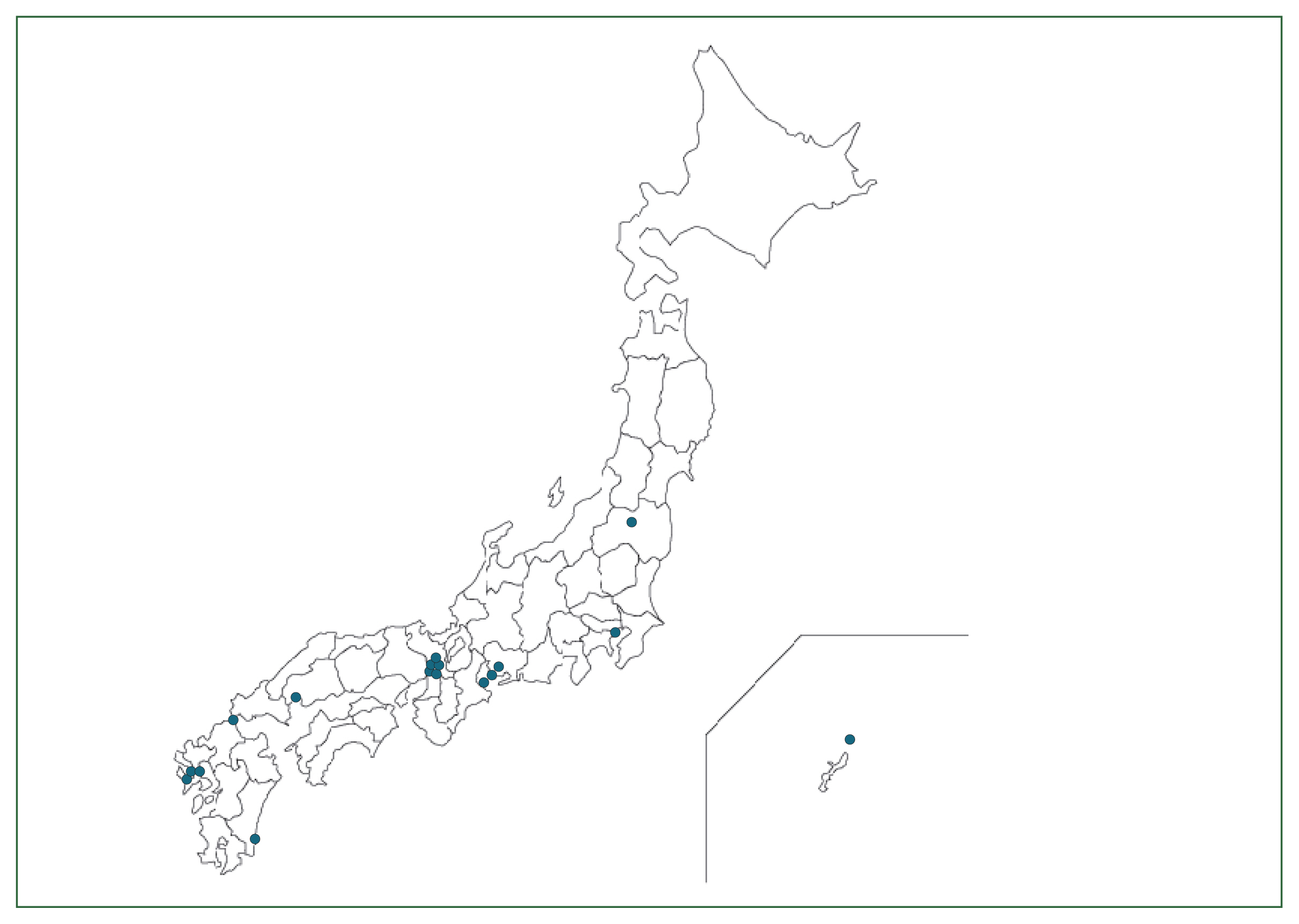

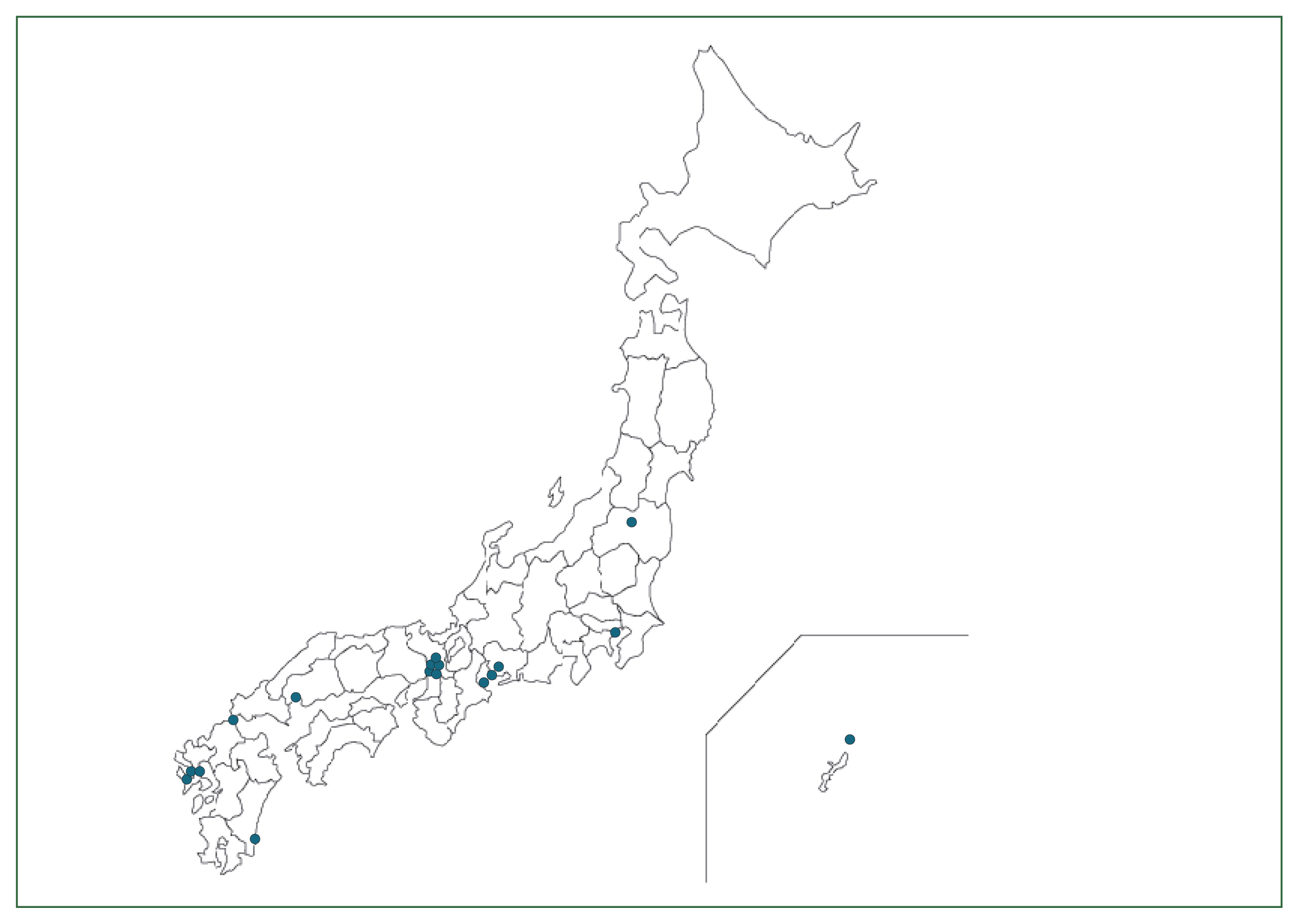

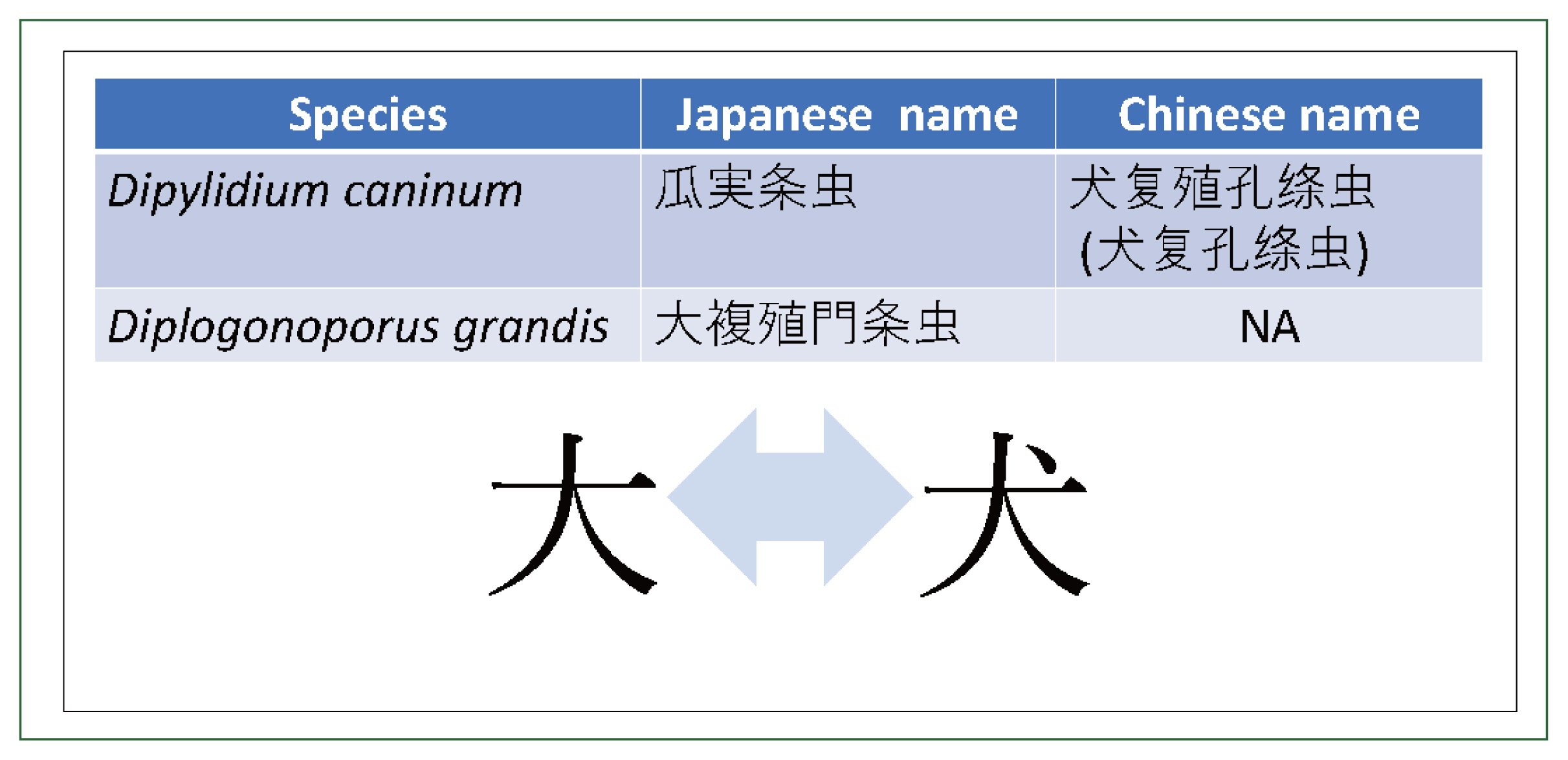

Fig. 3B). This erroneous translation had happened due to extremely high similarity of the Chinese name of

Dipylidium caninum “犬复殖孔绦虫” and the Japanese name of

Diplogonoporus grandis “大複殖門条虫”. Only a single tiny dot difference of the font caused misunderstanding (

Fig. 4). In Japan,

Dipylidium caninum is described as “瓜実条虫” which means a melon-seed-like tapeworm, which is quite different from the Chinese name of the same parasite. Fortunately for us, a few years ago, molecular taxonomic study revealed that

Diplognoporus grandis is a synonym of

Diplogonoporus balaenopterae [

32], which is further reclassified as

Diphyllobothrium balaenopterae, double-pored tapeworm of whales [

33], of which Japanese name is “鯨複殖門条虫” Thus, once this Japanese name has been recognized, such a confusion between China and Japan will never occur.

As is reviewed by Rousseau et al. [

2],

D. caninum is a cosmopolitan parasite and distributed worldwide where pet dogs and cats are available. Nevertheless, distribution of case reports of human dipylidiasis are largely deviated to Europe and U.S.A. and far less from Asian countries. To our best knowledge, there is no case report from Korea. Like this review, there might be more cases reported in local medical journals. Collaborative research across countries is necessary to elucidate actual situation of dipylidiasis in Asia.

In terms of the clinical point of view,

D. caninum infection is usually recognized first by mothers who find white rice grain-like moving creatures in the stool in the diapers of the child. Diagnosis can be made by the attending pediatricians demonstrating the typical morphological features of proglottids and/or egg packets in the stool. Praziquantel is a choice of the drug for the treatment of human dipylidiasis, 5–10 mg/kg orally in a single-dose therapy in adults. Although praziquantel is not approved for treatment of children less than 4 years old, it can be used successfully to treat dipylidiasis in children as young as 6 months (

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/dipylidium/health_professionals/index.html accessed on the 3rd January 2024).

In conclusion, dipylidiasis in humans is still sporadically occurring in Japan. Because the pathogenicity of D. caninum is generally not so serious, this zoonotic parasite might have low priority in public health. Even so, clinicians, especially pediatricians, should aware of the presence of this disease in this country and all over the world.

Notes

-

Conceptualization: Nawa Y, Furusawa A, Yoshikawa M

Data curation: Furusawa A, Tanaka M, Yoshikawa M

Formal analysis: Tanaka M, Yoshikawa M

Investigation: Furusawa A, Tanaka M, Yoshikawa M

Project administration: Nawa Y

Supervision: Nawa Y

Validation: Furusawa A, Tanaka M

Visualization: Nawa Y

Writing – original draft: Nawa Y

Writing – review & editing: Furusawa A, Tanaka M, Yoshikawa M

-

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.

Acknowledgment

A part of this study was presented orally at the 75th Japanese Society of Parasitology, Southern branch meeting held in the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University in 28–29th October 2023.

Fig. 1Moving creatures (arrows) in the stool of the patient recognized by his mother

Fig. 2Geographical distribution of dipylidiasis cases in Japan. Note that the majority of cases were from central and southwestern Japan.

Fig. 3The report of 2 cases of diplogonoporiasis by Kagei et al. [

31]. (A) Translated into Chinese and (B) original publication. Note the differences of the name of parasite in the title of the Chinese-translated and original versions, which is highlighted in

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Nomenclatures of Dipylidium caninum and Diprogonoporus grandis in Chinese and Japanese characters.

Table 1Dipylidiasis cases in Japan

Table 1

|

No. |

Age |

M/F |

Place |

Strobilae |

Scolex |

Symptom |

Treatment |

Dogs/cats |

Ref. |

Year |

|

1 |

6y |

F |

Aichi |

65 |

6 |

Vomit worm |

|

Cat |

[4] |

1925 |

|

2 |

1y |

F |

Osaka |

>10? |

ND |

|

Tymolx4 |

Dog |

[7] |

1942 |

|

3 |

1y 2m |

F |

Osaka |

2 |

ND |

Diarrhea, weight loss |

Not described |

Cat |

[8] |

1942 |

|

4 |

11m |

M |

Osaka |

1 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Camara 0.5 g |

Dog |

[9] |

1956 |

|

5 |

11m |

M |

Osaka |

2 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Camara 0.5 g |

Dog, cat |

[10,11] |

1956 |

|

6 |

58y |

F |

Hiroshima |

1 |

1 |

Appetite loss, soft stool, eggs in stool |

Camara 6.0 g |

Dog |

[12] |

1958 |

|

7 |

1y 3m |

F |

Tokyo? |

1 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Bexin, Pipenin sylop |

? |

[13] |

1960 |

|

8 |

11m |

F |

Nagasaki |

>10 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Santonin |

? |

[14] |

1960 |

|

9 |

2y 1m |

F |

Nagasaki |

7 |

4 |

Pica, Proglottids in stool |

Ateburin |

Cat |

[15] |

1961 |

|

10 |

7m |

M |

Aichi |

ND |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Anthelmintic |

Cat, dog |

[16] |

1971 |

|

11 |

6m |

M |

Kyoto |

8 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Yomezan 0.25 g x2 days |

Cat |

[17] |

1975 |

|

12 |

11m |

F |

Kagoshima |

16 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

Bithionol 25 mg/kg x2 |

Cats |

[18–20] |

1976 |

|

13 |

7m |

M |

Miyazaki |

1 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

PZQ 10 mg/kg |

Cat |

[21] |

1993 |

|

14 |

1y 2m |

F |

Mie |

1 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

PZQ 10 mg/kg |

Dog |

[22,23] |

1995

1996 |

|

15 |

1y 1m |

F |

Fukushima |

1 |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

PZQ 150 mg |

Cat |

[24] |

1997 |

|

16 |

1y 5m |

F |

Fukuoka |

4 |

4 |

Diarrhea, abdominal pain Proglottids in stool |

PZQ 10 mg/kg |

Dog, cat |

[25–27] |

2002 |

|

17 |

3y |

M |

Yamaguchi |

ND |

ND |

Proglottids in stool |

None |

Cat |

In this review |

2021 |

References

- 1. Sapp SGH, Bradbury RS. The forgotten exotic tapeworms: a review of uncommon zoonotic Cyclophyllidea. Parasitology 2020;147(5):533-558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202000013X

- 2. Rousseau J, Castro A, Novo T, Maia C. Dipylidium caninum in the twenty-first century: epidemiological studies and reported cases in companion animals and humans. Parasit Vectors 2022;15(1):1-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05243-5

- 3. Jiang P, Zhang X, Liu RD, Wang ZQ, Cui J. A human case of zoonotic dog tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (Eucestoda: Dilepidiidae), in China. Parasites Hosts Dis 2017;55(1):61-64. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2017.55.1.61

- 4. Tamura Y, Maekawa T. Demonstration of Dipylidium caninum specimen from a patient. Aichi Med J 1925;32(3):591-597. (in Japanese).

- 5. Kagei N. Hymenolepis nana, Hymenolepis dimunuta and Dipylidium caninum infections. Syonika (Pediatrics) Mook 1983;28:114-121. (in Japanese).

- 6. Ando K. A human case of Dipylidium caninum infection. Infect Agents Surv Rep, NIID, Japan 1995;16(1995/10[188]):(in Japanese).

- 7. Iwata M, Kobayashi M. A rare case of human dipylidiasis. Osaka-Iji-Shinshi 1942;13(9):963-968. (in Japanese).

- 8. Kasahara M, Tomono S. Dipylidium caninum. Jikken-Iho (Exp Med) 1942;29(1):43-45. (in Japanese).

- 9. Morishita K, Nishimura T, Tabuchi Y. A case of Dipylidium caninum infection. Tokyo-Iji-Shinshi 1956;3(1):28. (in Japanese).

- 10. Ikeda K, Omori Y. A case of dipylidiasis. Jpn Red Cross Med J 1956;9(2):125-127. (in Japanese).

- 11. Omori Y, Ikeda K. A case of dipylidiasis. Jpn J Pediatr 1956;9(1):89-90. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 12. Asada J, Ochi K, Dohi S, Kaji F. A human case of Dipylidium caninum infection. Tokyo-Iji-Shinshi 1958;75(8):25-26. (in Japanese).

- 13. Ebihara T, Iwata M. A case of dipylidiasis canina. J Pediatr Pract 1960;23:149. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 14. Kusano M, Ueda Y, Deguchi M, Sato D. A case of dipylidiasis. J Pediatr Pract 1960;23:1017-1019. (in Japanese).

- 15. Kusano M, Kurimura Y. A case of dipylidiasis with pica. Arch Sasebo City Hospital 1961;5:33-36. (in Japanese).

- 16. Iwata M, Sakui K, Tsuruta H. Dipylidium caninum in man. Jpn J Parasitol 1971;20(2):52. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 17. Yoshida Y, Kondo K, Arizono N, Okamoto K, Ogino K, et al. A case of Dipylidium caninum infection in an infant. Jpn J Parasitol 1975;24:20. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 18. Ono S, Takaoka H. A human case of Dipylidium caninum. J Jpn Pediatr Soc 1976;80(6):442-443. (Abstract, in Japanese).

- 19. Ono S, Terawaki T, Takaoka H, Sato A. A human case of Dipylidium caninum. Jpn J Parasitol 1976;25(1):36-37. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 20. Ono S, Fukami H, Sato A, Takaoka H. A case of human dipylidiasis. J Pediatr Pract 1977;40(5):557-560. (in Japanese).

- 21. Watanabe T, Horii Y, Nawa Y. A case of Dipylidium caninum infection in an infant – The first case found in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. Jpn J Parasitol 1993;42(3):234-236.

- 22. Ando K. Human infection with Dipylidium caninum. IASR 1995;10:188. (in Japanese).

- 23. Miyahara M, Ihara T, Kamiya I, Ando K. A case of dipylidiasis. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis 1996;70(5):536. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 24. Sakata T, Nagaoka T, Kawanaka M. A case of dipylidiasis in Tohoku, Japan. Clin Parasitol 1997;8(1):146-148. (in Japanese).

- 25. Ueda M, Kanbe T, Kuwahata S, Yamato Y, Otsu Y, et al. Dipylidiasis in an infant. J Jpn Pediatr Soc 2002;106:959-960. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 26. Otsu Y, Kuwahata F, Tsumura N, Masunaga K, Ishimoto K. Dipylidiasis in an infant. J Pediatr Infect Dis Immunol 2003;15(3):339. (Abstract only, in Japanese).

- 27. Tsumura N, Koga H, Hidaka H, Mukai F, Ikenaga M, et al. Dipylidium caninum infection in an infant. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis 2007;81(4):456-458. (in Japanesehttps://doi.org/10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.81.456

- 28. Morishima Y, Sugiyama H, Arakawa K, Kawanaka M. Intestinal helminths of dogs in northern Japan. Vet Rec 2007;160(20):700-701. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.160.20.700

- 29. Yamamoto N, Kon MA, Saito TO, Maeno N, Koyama MA, et al. Prevalence of intestinal canine and feline parasites in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis 2009;83(3):223-228. (in Japanesehttps://doi.org/10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi.83.223

- 30. Luo ZH. Parasitology Section. Foreign Med Sci 1982;(04):180-181. (in Chinese).

- 31. Kagei N, Hayashi S, Kato K, Masu H. The second case of diplogonoporiasis grandis discovered in Kanagawa Prefecture and anthelmintic effect of paromomycin sulphate. Jpn J Parasitol 1981;30(5):457-465. (in Japanese).

- 32. Yamasaki H, Ohmae H, Kuramochi T. Complete mitochondrial genomes of Diplogonoporus balaenopterae and Diplogonoporus grandis (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) and clarification of their taxonomic relationship. Parasitol Int 2011;61(2):260-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2011.10.007

- 33. Waeschenbach A, Brabec J, Scholz T, Littlewood DT, Kuchta R. The catholic taste of broad tapeworms–multiple routes to human infection. Int J Parasitol 2017;47(13):831-843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.06.004

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by