Abstract

Recent advances in radiological and serological techniques have enabled easier preoperative diagnosis of sparganosis. However, due to scarcity of cases, sparganosis has been often regarded as a disease of other etiologic origin unless the parasite is confirmed in the lesion. We experienced a case of sparganosis mimicking a varicose vein in terms of clinical manifestations and radiological findings. Sparganosis should be included among the list of differential diagnosis with the varicose vein.

-

Key words: sparganosis, varicose vein, subcutaneous mass

INTRODUCTION

Sparganosis is a larval cestode disease caused by infection with the plerocercoid of the genus

Spirometra. The disease is usually manifested with migrating subcutaneous masses, but may also involve the oral cavity (

Iamaroon et al., 2002), brain (

Sundaram et al., 2003), pleura (

Ishii et al., 2001), bone (

Settakorn et al., 2002) and scrotum (

Jeong, 2004). Most of the diseases are diagnosed by surgical pathology specimens. However, due to recent advances in serological (

Kim et al., 1984;

Lee et al., 2002) and radiological techniques (

Cho et al., 2002), proper diagnosis could be established prior to surgery. We report a case of subcutaneous and muscular sparganosis that was initially misdiagosed as a varicose vein. Since this infection is rare and physicians have little experience of sparganosis, the diagnosis is still frequently confused with other diseases until the worm is confirmed from the mass lesion.

CASE RECORD

A 44-year-old woman presented with an increasing crackle in her knee of a month's duration. She had previously noticed a small mass in the left popliteal area some 10 years previously. The lesion extended to the medial side of the knee and thigh, but she ignored this as the condition was asymptomatic. She had no history of leg trauma and denied ingesting raw snake or frog, but admitted drinking from a spring occasionally when she climbed mountain areas for exercise.

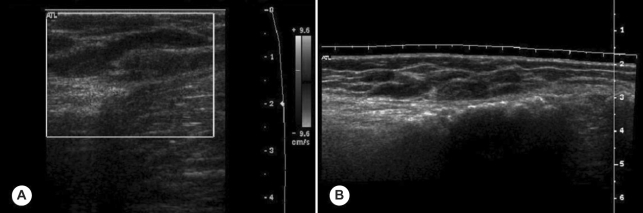

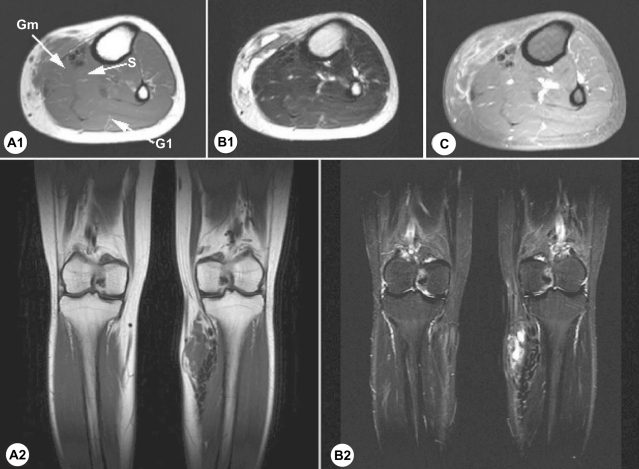

On physical examination, relatively ill defined, variously sized, round or elongated, soft nodules were detected on the medial aspect of her left leg and popliteal fossa. Routine laboratory test results were within reference ranges, and no leukocytosis and no eosinophilia was detected in the peripheral blood. A plain knee radiograph taken at a primary clinic demonstrated multiple discoid calcifications around her knee (

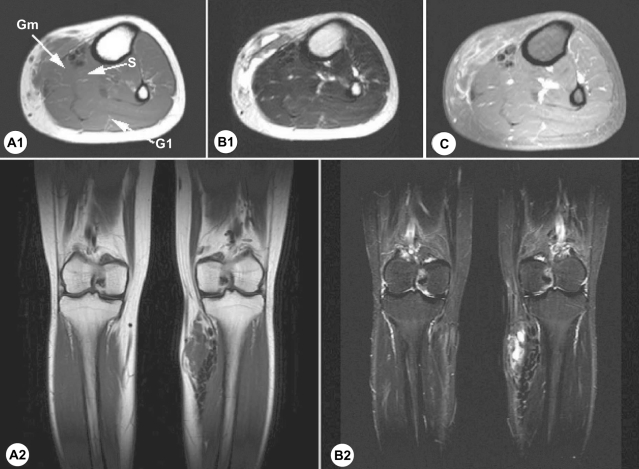

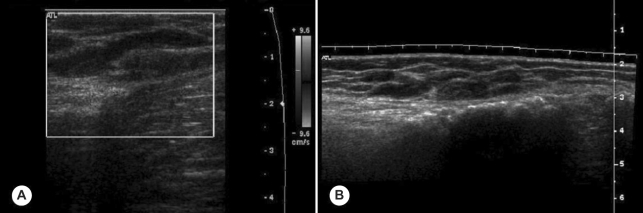

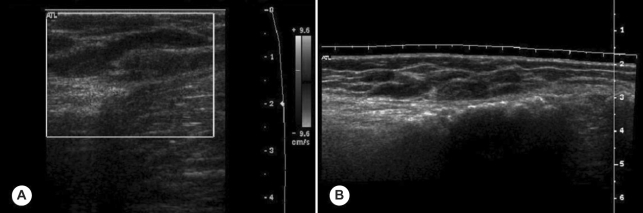

Fig. 1). Ultrasonography revealed subcutaneous hypoechoic elongated nodules and irregular intramuscular calcifications in the left lower leg antero-medially with slightly increased peripheral vascularity. Elongated and dilated superficial veins were also identified along the hypoechoic nodule and this showed compressibility at the same time (

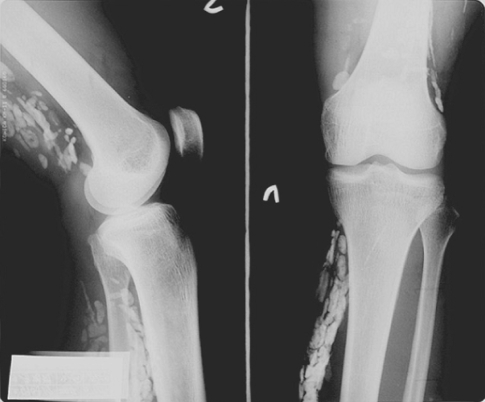

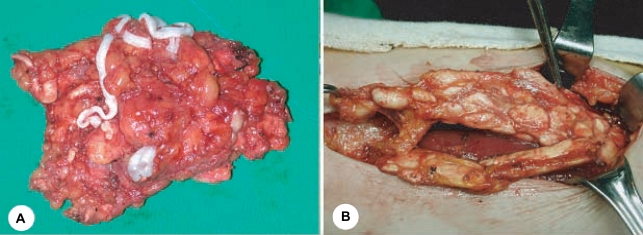

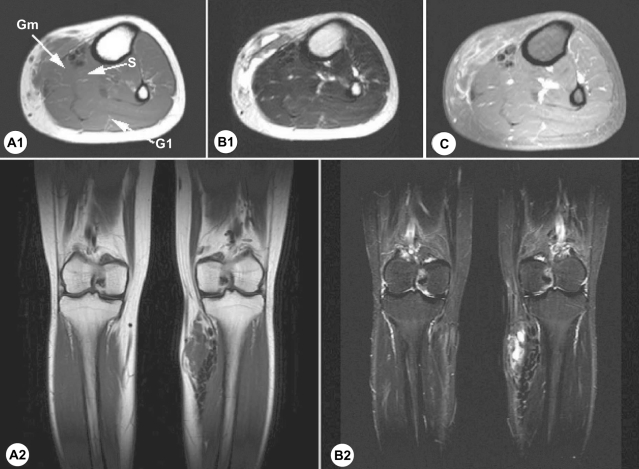

Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging revealed a multilocular (tubular and round) subcutaneous lesion (width 45 mm, thickness 15 mm, length 75 mm) in the antero-medial aspect of the proximal left lower leg. The lesion showed low signal intensity on T1 weighted images, high and low signal intensities on T2 weighted images, and irregular thick rim enhancement. Numerous calcific foci were noted along the medial margin of the soleus and medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. Sporadic intra- and intermuscular calcific foci were also noted at the postero-lateral portion of the distal thigh, which showed faint rim enhancement (

Fig. 3). The preoperative diagnosis was made as a partly thrombosed varicose vein associated with myositis at adjacent muscles.

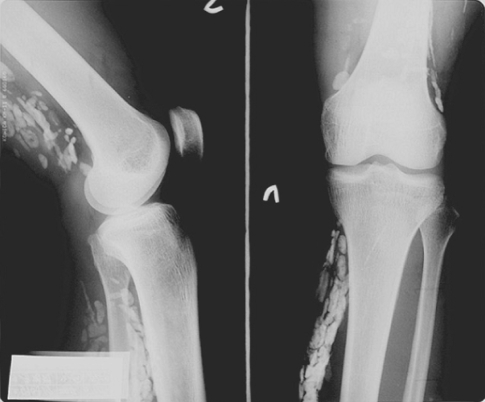

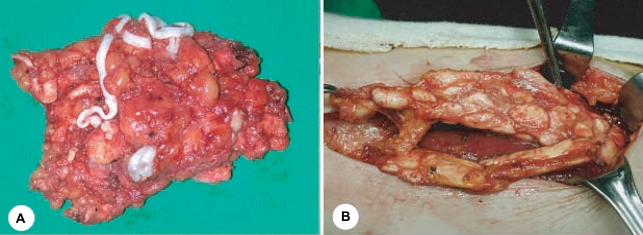

During the surgery, a small longitudinal incision was made over the elongated mass to remove the conglomerated vascular lesion at the same time. The approached mass through the incision site had a yellowish-white color capsule which contained an ivory-colored, opaque and ribbon-shaped sparganum that measured 30 cm in length and 0.5 cm in width, and this was correspondent to the hypoechoic elongated mass on ultrasonography. Many pieces of encapsulated and mummified sparganum were detected at subfascial muscular layers, and these corresponded with the areas of calcified foci on MR images. All of these masses were removed by extending the incision and complete dissection was possible from adjacent soft tissues (

Fig. 4). On the third postoperative day, the patient was discharged and followed-up uneventfully.

DISCUSSION

Sparganosis is a rare disease, but sporadically detected throughout the world. The disease is characterized by a slow-growing, sometimes migratory, subcutaneous mass. When mass lesions are detected at subcutaneous layers, the diagnosis can be made by surgical biopsy, but before surgery other diagnostic possibilities such as inflammatory, neoplastic, or vascular disorders must be considered. Recently developed imaging diagnostic modalities may solve these diagnostic problems easily, but in some cases, precise diagnosis can be missed due to a lack of suspicion by the primary physician.

On plain radiographs, calcification has been reported as an important diagnostic clue of cerebral sparganosis (

Chang et al., 1992;

Dunn and Palmer, 1998). The sonographic findings include a linear echogenicity with a 'dot and dash' pattern in some portion of the tract, which is a highly characteristic finding of sparganosis (

Cho et al., 2002). Our patient also disclosed similar findings, but dilated veins along and around mass with compressibility on ultrasonography made us confusing the diagnosis. The live sparganum, with an overlying soft capsule, was misinterpreted as a partly thrombosed varicose vein. MR images of muscular sparganosis are conglomerated cystic lesions and reactive changes in the adjacent soft tissues. The imaging appearance of the cystic lesions with surrounding reactive changes may resemble pyogenic infections, other parasitic infections (cysticercosis and paragonimiasis) or hemangioma, and these must be differentiated. Moreover, if serpiginous tubular tracts are observed during imaging studies, musculoskeletal sparganosis should be included in the differential diagnosis (

Cho et al., 2002). Laminated calcospherules in the cytoplasm of proliferating macrophages and giant cells are of diagnostic value if no sparganum worm is present in a lesion (

Chi, 1980).

The present sparganosis case mimicked a varicose vein in terms of clinical manifestations and radiological findings. Sparganosis should be included among the list of differential diagnosis with varicose vein.

References

Fig. 1Plain radiographs showing multiple discoid calcifications around the affected knee.

Fig. 2Ultrasonography showing elongated and dilated superficial veins along the hypoechoic nodule (A), and oval, cystic lesions in subcutaneous tissue (B).

Fig. 3Axial (A1) and coronal (A2) T1-weighted MR image showing low signal intensity in subcutaneous tissue. Axial (B1) and coronal (B2) T2-weighted MR images showing high signal intensity in subcutaneous tissue and low signal intensity with irregular thick rim enhancement at the medial margin of the soleus, medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle, and in the distal thigh posterolaterally. Gadolinium-enhanced MR image (C) showing a non-enhanced lesion in an intramuscular portion; Gm, gastrocnemius medial head, Gl, gastrocnemius lateral head, S, soleus.

Fig. 4Gross specimen from the left thigh showing a live sparganum, which was removed from a rubbery elongated capsule located at a subcutaneous fat layer (A). After the mass removal, multiple discoid calcific chains were observed under the muscular fascia (B), which contained a mummified sparganum.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A hidden traveler in the brain: A 19-year odyssey of migratory cerebral sparganosis

Prasert Iampreechakul, Chonlada Angsusing, Sunisa Hangsapruek, Punjama Lertbutsayanukul, Thananan Phothi, Samasuk Thammachantha, Adisak Tanpun, Ratirath Samol, Ekkarong Suwanwech

Surgical Neurology International.2025; 16: 550. CrossRef - Hand palm sparganosis: morphologically and genetically confirmed Spirometra erinaceieuropaei in a fourteen-year-old girl, Egypt

Hussein M. Omar, Magdy Fahmy, Mai Abuowarda

Journal of Parasitic Diseases.2023; 47(4): 859. CrossRef - Proteomic and Immunological Identification of Diagnostic Antigens from Spirometra erinaceieuropaei Plerocercoid

Yan Lu, Jia-Hui Sun, Li-Li Lu, Jia-Xu Chen, Peng Song, Lin Ai, Yu-Chun Cai, Lan-Hua Li, Shao-Hong Chen

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2021; 59(6): 615. CrossRef - Diagnostic Efficacy of a Recombinant Cysteine Protease of Spirometra erinacei Larvae for Serodiagnosis of Sparganosis

S.M. Mazidur Rahman, Jae-Hwan Kim, Sung-Tae Hong, Min-Ho Choi

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(1): 41. CrossRef - A Case of Inguinal Sparganosis Mimicking Myeloid Sarcoma

Jin Yeob Yeo, Jee Young Han, Jung Hwan Lee, Young Hoon Park, Joo Han Lim, Moon Hee Lee, Chul Soo Kim, Hyeon Gyu Yi

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2012; 50(4): 353. CrossRef - A Case of Sparganosis in the Leg

Kyung-Joon Lee, Na-Hye Myung, Hyun-Woo Park

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2010; 48(4): 309. CrossRef - Breast and Scrotal Sparganosis

Su Jin Hong, You Me Kim, Min Seo, Kyu Soon Kim

Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine.2010; 29(11): 1627. CrossRef - A surgically confirmed case of breast sparganosis showing characteristic mammography and ultrasonography findings

Jae-Hwan Park, Jee-Won Chai, Nariya Cho, Nam-Sun Paek, Sang-Mee Guk, Eun-Hee Shin, Jong-Yil Chai

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2006; 44(2): 151. CrossRef