Abstract

Avian schistosomes, mainly belonging to the genus Trichobilharzia, are the etiological agents of cercarial dermatitis in humans. The aims of this study were to report a human case of cercarial dermatitis contracted in a paddy field in a natural regeneration area in Tokyo, Japan, and identify the etiological agents of this case using molecular phylogenetic analyses. A snail survey was conducted between 2021 and 2023 in a rice paddy field where a case of cercarial dermatitis occurred, and molecular phylogenetic analyses of the furcocercariae and parasitized lymnaeid snails were performed based on the partial sequence of the mtDNA cox1 gene. Furcocercariae were detected in 11 (2.7%) of the 413 lymnaeid snails examined, and all 120 pleurocerid snails tested negative for cercariae. The cercarial larvae possessed a pair of eye spots and a characteristic bifurcated tail. Phylogenetic analyses of the cox1 genes identified the furcocercariae as Trichobilharzia sp., and the lymnaeid snails were Radix plicatula. This study demonstrated that the life cycle of a Trichobilharzia sp., using R. plicatula as an intermediate host, is established in an urban natural restoration area in Tokyo, serving as a source of human cercarial dermatitis. This study emphasizes the need for an increased awareness of cercarial dermatitis as a potential public health concern.

-

Key words: Cercarial dermatitis, paddy field dermatitis, Trichobilharzia, Radix plicatula, Japan

Introduction

Schistosomatidae (Platyhelminthes, Neodermata, Trematoda) are widely known blood flukes that parasitize birds and mammals, including humans. The genus

Trichobilharzia Skrjabin and Zakharov, 1920, is the most speciose within this family, encompassing approximately 40 nominal species [

1,

2].

Trichobilharzia spp. utilize wild waterfowl as definitive hosts and freshwater snails as intermediate hosts, but incidental cercarial infections of humans can occur [

3]. Humans are “dead-end” hosts, meaning that invading cercariae ultimately die within the host. However, invading cercariae have the potential to induce a strong allergic reaction in human hosts. Initial symptoms include erythema and itching, followed by development of a maculopapular rash on areas of skin that have been submerged in water within 12–48 h of exposure [

4,

5].

Cercarial dermatitis was observed by Dr. William W. Cort at Douglas Lake, Michigan, USA, when collecting snails for biological specimens in 1928. He found that the cercariae of avian schistosomes,

Cercaria elvae from snails, induced a rash after penetrating the skin, and he described this allergic reaction as cercarial dermatitis [

6]. Since that time, cases of cercarial dermatitis have been reported worldwide. This is because the pathogens parasitize migratory birds, which facilitates widespread dispersal of parasite eggs.

Tanabe [

7] was the first to report the cause of a well-known dermatitis among paddy field workers in the valley area adjacent to Lake Shinji in Shimane Prefecture, Japan. Known locally in Japan as “Koganbyo” (lakeside disease), his report indicates that the condition was caused by penetration of the skin by cercariae of

Gigantobilharzia sturniae. Cort reported that this dermatitis was similar to the condition commonly referred to as “swimmer’s itch” in many parts of the world [

8]. Thereafter, cases of dermatitis resulting from skin penetration by cercariae of

T. physellae and

T. szidati (formerly referred to as

T. ocellata, see [

9]) at Oki Island, Shimane Prefecture [

10], Japan, and

T. brevis in Saitama Prefecture, Japan [

11], were also reported, indicating that paddy fields could serve as sources of cercarial dermatitis in various parts of Japan. However, since the 1990s, few reports of cercarial dermatitis have been reported in Japan, and as a result, it has become one of the lesser-known parasitic diseases.

In 2021, a worker developed an itchy skin rash on his legs after working in a paddy field in Tokyo, Japan. This paddy field is located within a natural restoration area, and the flight of ducks to the paddy field and the presence of snails have been confirmed. Therefore, we suspected it to be a case of cercarial dermatitis. The aims of this study were to report a human case of cercarial dermatitis contracted in a paddy field in a natural regeneration area in Tokyo, Japan, and identify the etiological agents of this case and its intermediate snail hosts using molecular phylogenetic analyses. Although identification of cercariae at the family level is generally possible based on morphology, more specific identification requires the use of molecular tools. Several studies have demonstrated that morphological characterization of cercariae is unreliable for identifying species of the genus

Trichobilharzia [

1,

12-

14]. Accurate identification of the snail species is often critical for precise identification of schistosome species, as schistosomes exhibit a strong preference for particular snail species as hosts [

1,

15]. Based on these considerations, molecular analyses were conducted in this study to identify both the schistosome species and their snail hosts. As a result, we demonstrated the life cycle of

Trichobilharzia in an urban natural restoration area, indicating an emerging interface between wildlife parasites and human activities. This study highlights the importance of recognizing the potential risk of cercarial dermatitis and the need for integrated approaches to both biodiversity and public health management for this zoonotic disease.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. Ethical approval was not required because this was a single anonymized case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Description of a cercarial dermatitis case

In June 2021, a male worker in a natural restoration paddy field in Tokyo, Japan, presented with an itchy rash on his legs, which had been submerged in paddy field water (

Fig. 1). Lesions developed within hours of contact with the paddy field water. The worker reported that dermatologic symptoms, including itching, had been observed in other individuals who had been in contact with the paddy field water within approximately the last year.

Snail samples were collected by hand from the abovementioned small paddy field 4 to 7 times per year between 2021 and 2023. Snail sampling was basically performed until consecutive negative results for cercariae of avian schistosomes were confirmed. The collected snails were transported to the laboratory after being placed in plastic containers filled with paddy field water. At the laboratory, the snails were cracked open with pliers in a petri dish filled with distilled water and examined under a stereomicroscope for the presence of cercariae. Cercariae with a bifurcated tail were identified as furcocercariae. Detected furcocercariae were transferred to water for injection, and each was placed in a PCR tube with 10 μl of water using a micropipette and stored at -20°C until DNA extraction. The remaining furcocercariae were preserved in 70% alcohol as preliminary samples for molecular identification. For each snail, a small piece of the posterior foot was trimmed and stored at -20°C for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing of cercarial DNA

In this study, we used molecular analysis to identify the species of 5 furcocercariae randomly selected from each snail. DNA was extracted using an alkaline lysis method. Whole furcocercariae were lysed in 25 μl of 0.02 N NaOH at 99°C for 30 min.

First, PCR amplification of nuclear 28S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was carried out according to a previous report [

16]. The primer pair LSU-5 (5’-TAGGTCGACCCGCTGAAYTTAAGCA-3’) and 1500R (5’-GCTATCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG-3’) was utilized for PCR. These primers were also used for sequencing. Three additional primers were synthesized and used to focus on regions not accessible using the PCR primers: 300F (5’-CAAGTACCGTGAGGGAAAGTT-3’), 300FR (5’-AACTTTCCCTCACGGTACTTG-3’), ECD2 (5’-CTTGGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGGG-3’), and ECD2R-for (5’- CCCGTCTTGAAACACGGACCAAG-3’). For identification of

Trichobilharzia spp., PCR amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome

c oxidase subunit 1 (

cox1) was performed using the following degenerate primer pair, CO1F15 (forward: 5'-TTTNTYTCTTTRGATCATAAGC-3’) with CO1R15 (reverse: 5'-TGAGCWAYHACAAAYCAHGTATC-3’) [

2]. PCR conditions were as follows: initial DNA denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min 30 sec, followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. PCR amplification of the

cox1 gene was carried out in a 25-μl reaction containing 1 μl of template DNA, 0.6 U of TaKaRa EX Taq (TaKaRa Bio), 0.6 μM each primer, and the manufacturer’s 1× Ex Taq buffer, using a Gene Atlas G02 gradient thermal cycler (Astec). Water for injection was used instead of the DNA template as a negative control. The PCR products were directly sequenced in both directions by Eurofins Genomics using the primers described above.

Total DNA was extracted from a small piece of tissue from each of 8 snails (4 infected and 4 uninfected) using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplification of the

cox1 gene was performed utilizing the primer pair LCO1490 (5'-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3') and HCO2198 (5'-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3') [

17]. Template DNA or water for injection (as a negative control) was added to 25 μl PCR preparations. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial DNA denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 45°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. Direct sequencing analysis was performed in both directions using PCR primers.

The resulting sequences obtained by PCR were analyzed using GeneStudio Pro version 2.2 (GeneStudio) and compared with sequences in the GenBank database using the NCBI BLAST program (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The sequences obtained in this study were aligned with those of respective

Trichobilharzia species or respective lymnaeid snail species previously deposited in GenBank using the MUSCLE program. In addition, pairwise distance (p-distance) values were calculated among sequences within the genus

Trichobilharzia using MEGA X software [

18]. Phylogenetic analyses were subsequently performed using the maximum-likelihood method with MEGA X software.

Schistosoma bovis (AY157212) was used as the outgroup for analyses of

Trichobilharzia species, and

Physella acuta (JQ390525) was used as the outgroup for analyses of lymnaeid snails. The best-fit nucleotide substitution models for phylogenetic analyses were selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion. The TN93+G+I model was employed for

Trichobilharzia, whereas the GTR+G+I model was employed for snails. Individual nodes were evaluated by bootstrap resampling with 1,000 replications.

Results

Prevalence of schistosome cercariae

Lymnaeid snails were collected in July and September 2021 and then again in April to September 2022 and April to October 2023. Conversely, the survey of pleurocerid snails was concluded in July 2021 because the absence of cercariae was confirmed in 2 consecutive surveys. A total of 413 lymnaeid snails and 120 pleurocerid snails were analyzed, and furcocercariae were found in 11 lymnaeid snails (2.7%). The prevalence of furcocercariae by collection date over 3 years is shown in

Table 1. The detected cercarial larvae possessed a pair of eye spots, a ventral sucker, and a characteristic bifurcated tail (

Fig. 2).

Sequencing of 28S rDNA from a furcocercaria indicated a length of 1,304 bp. A database search of that sequence using NCBI BLAST showed the highest similarity (99.8%) with the sequence of Trichobilharzia sp. (OK104140) and hits with members of the genus Trichobilharzia with ≥97% identity. Accordingly, this cercaria was identified as belonging to the genus Trichobilharzia. The sequence was submitted to GenBank under accession number LC860981.

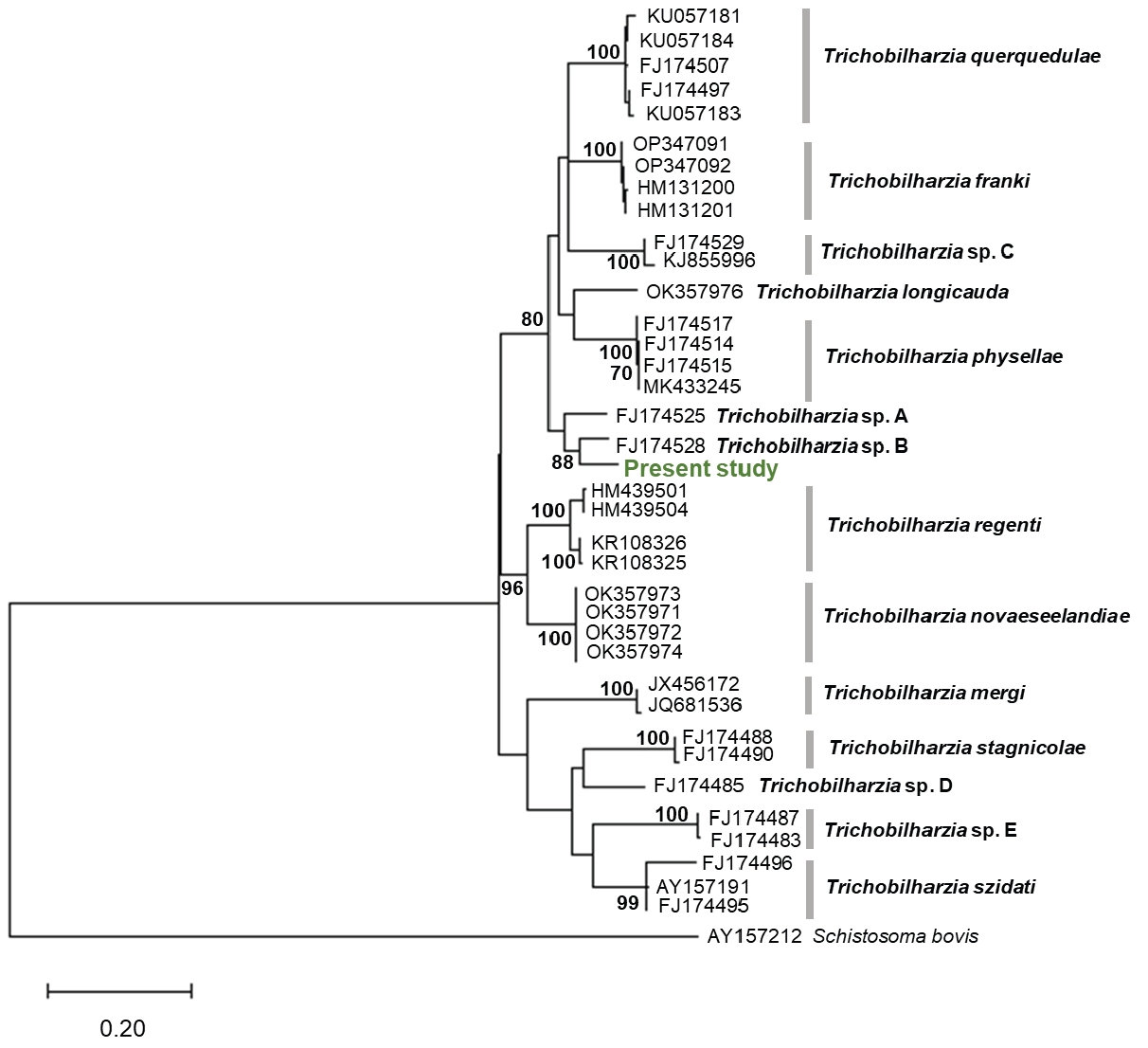

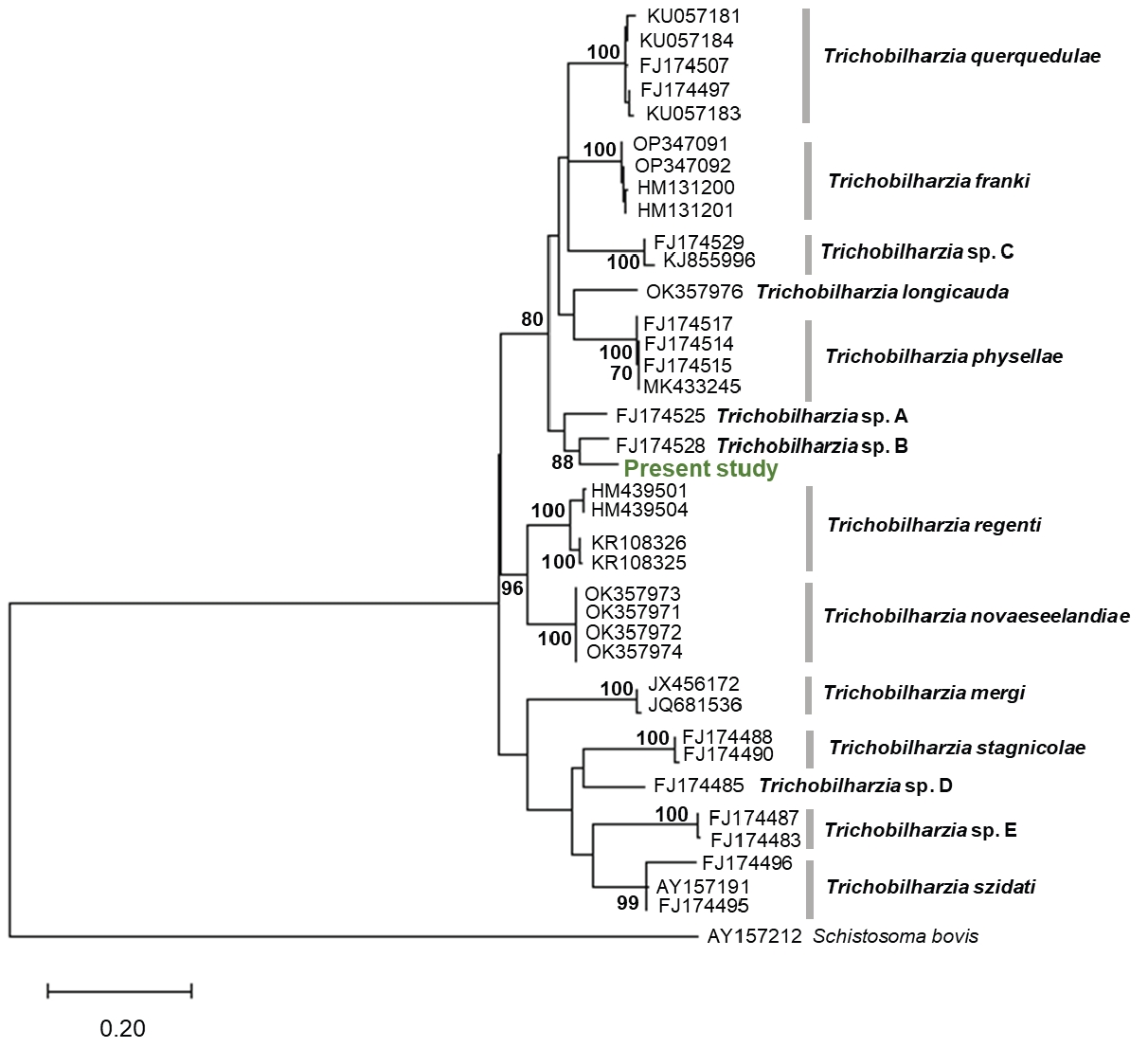

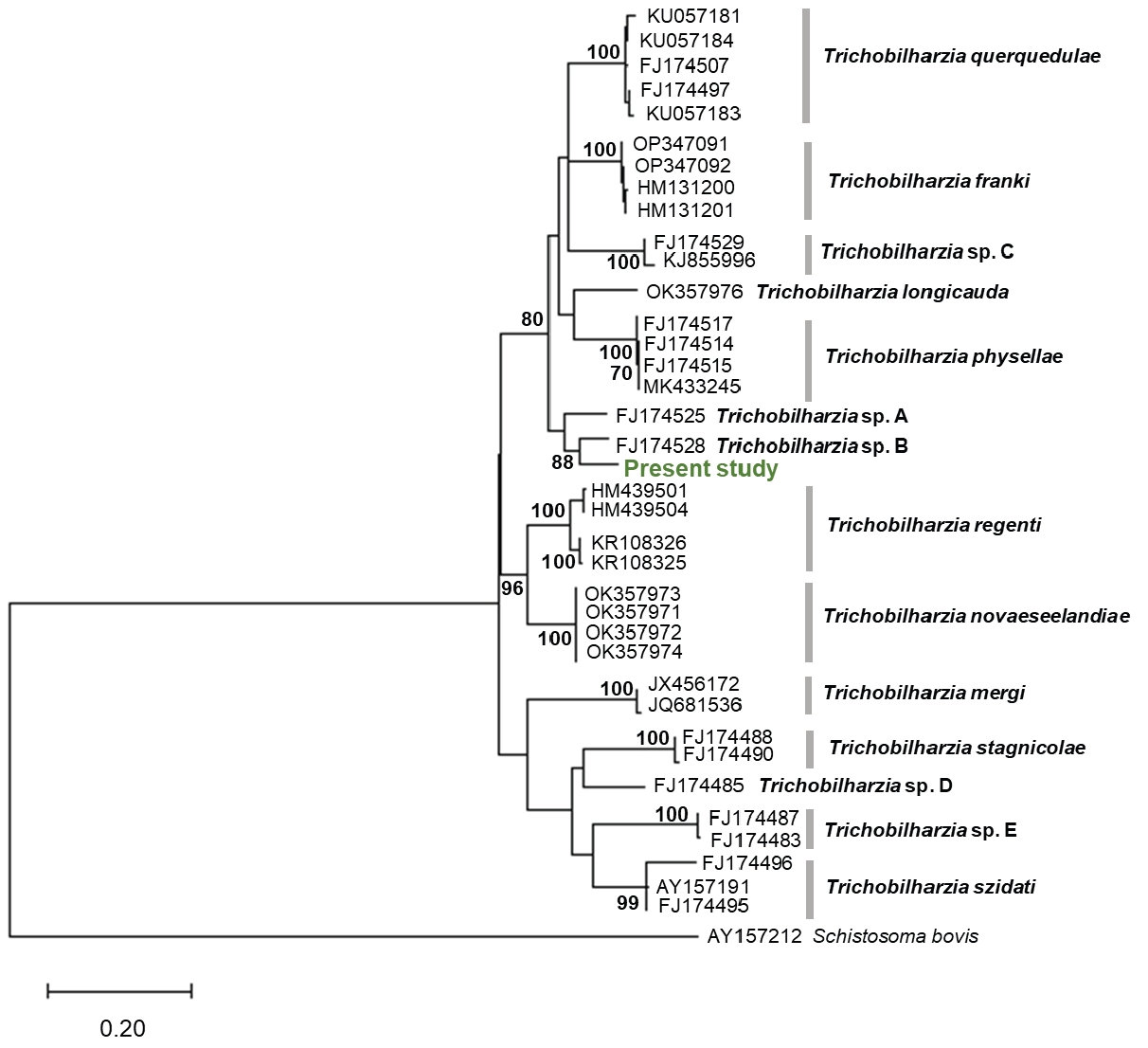

Phylogenetic analysis of furcocercariae based on sequencing of the cox1 gene

The partial sequence of the mitochondrial cox1 gene proved to be a valuable tool for distinguishing between species of the genus Trichobilharzia due to its requisite variation for species discrimination. The cox1 products of approximately 1,000 bp were generated through PCR. Subsequently, the obtained DNA sequences were trimmed of low-quality regions at both ends, resulting in a determined sequence of 800 bp in both directions. No differences were detected in the sequences between the worms. The sequence was submitted to GenBank under the number LC860982.

BLASTn analysis revealed that the sequence showed the highest similarity (94.0%) with that of

Trichobilharzia sp. B (FJ174528), which was reported in the United States. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the partial

cox1 sequences of the obtained cercariae and those of additional related species of the genus

Trichobilharzia available from GenBank. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that the isolates in the present study did not group with known species in the tree and thus did not allow for species identification (

Fig. 3).

Uncorrected p-distances between and within

Trichobilharzia species, as estimated from

cox1 gene sequences, are presented in

Table 2. The estimated uncorrected p-distance between and within these species ranged from 7.2% to 12.1% and 0.1% to 2.2%, respectively. Furthermore, the uncorrected p-distance between

Trichobilharzia sp. B and the cercariae of

Trichobilharzia sp. in the present study was 6.0%.

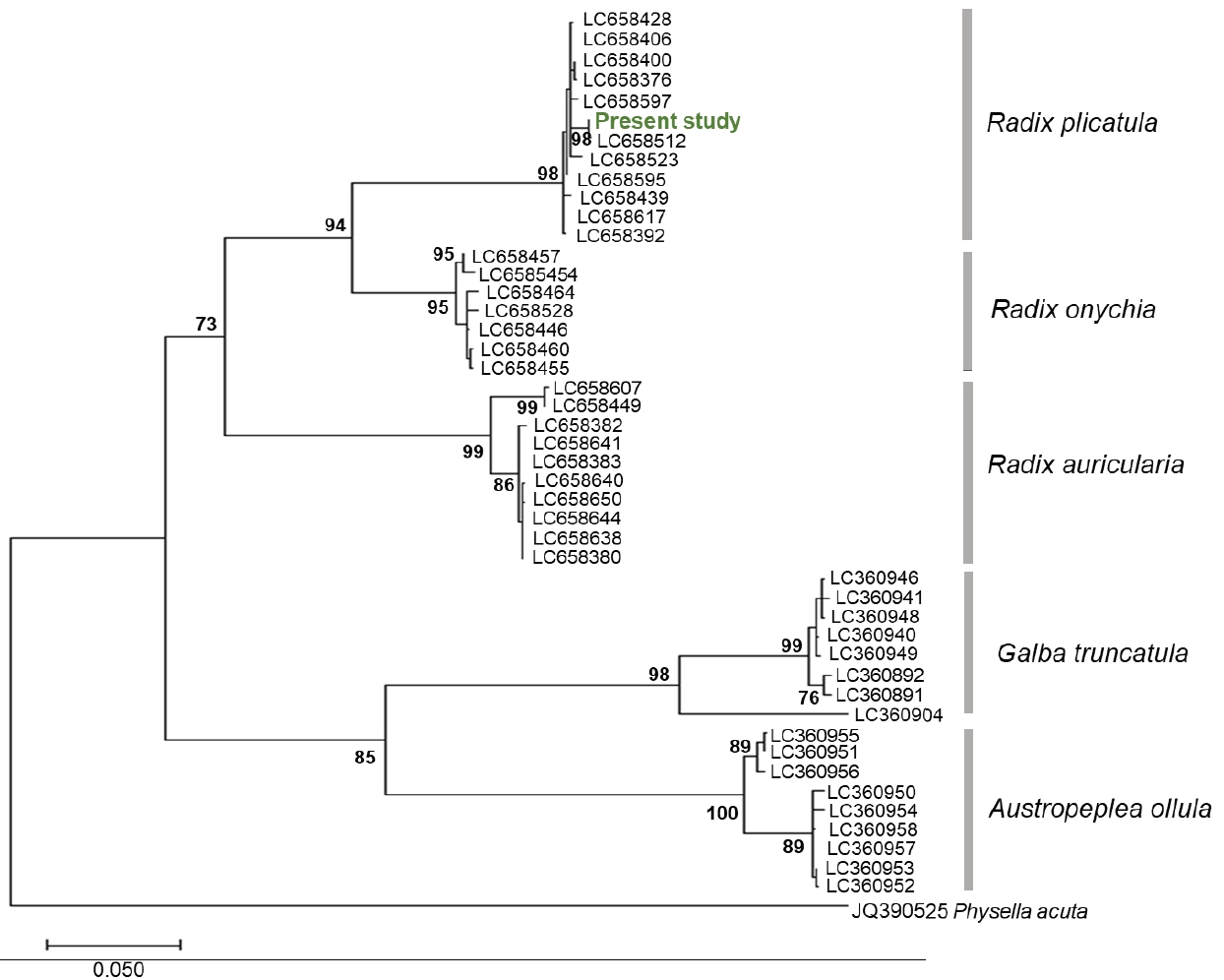

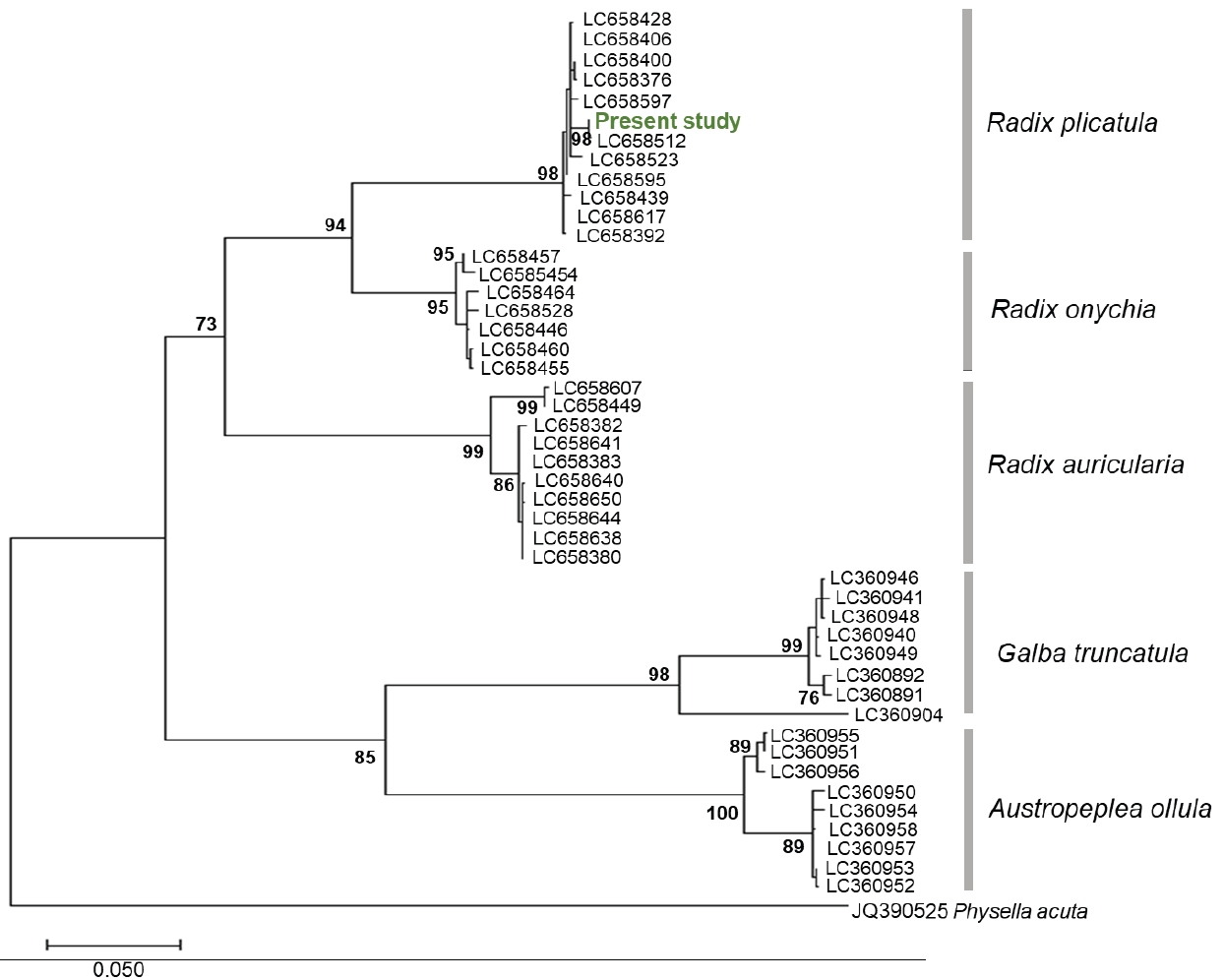

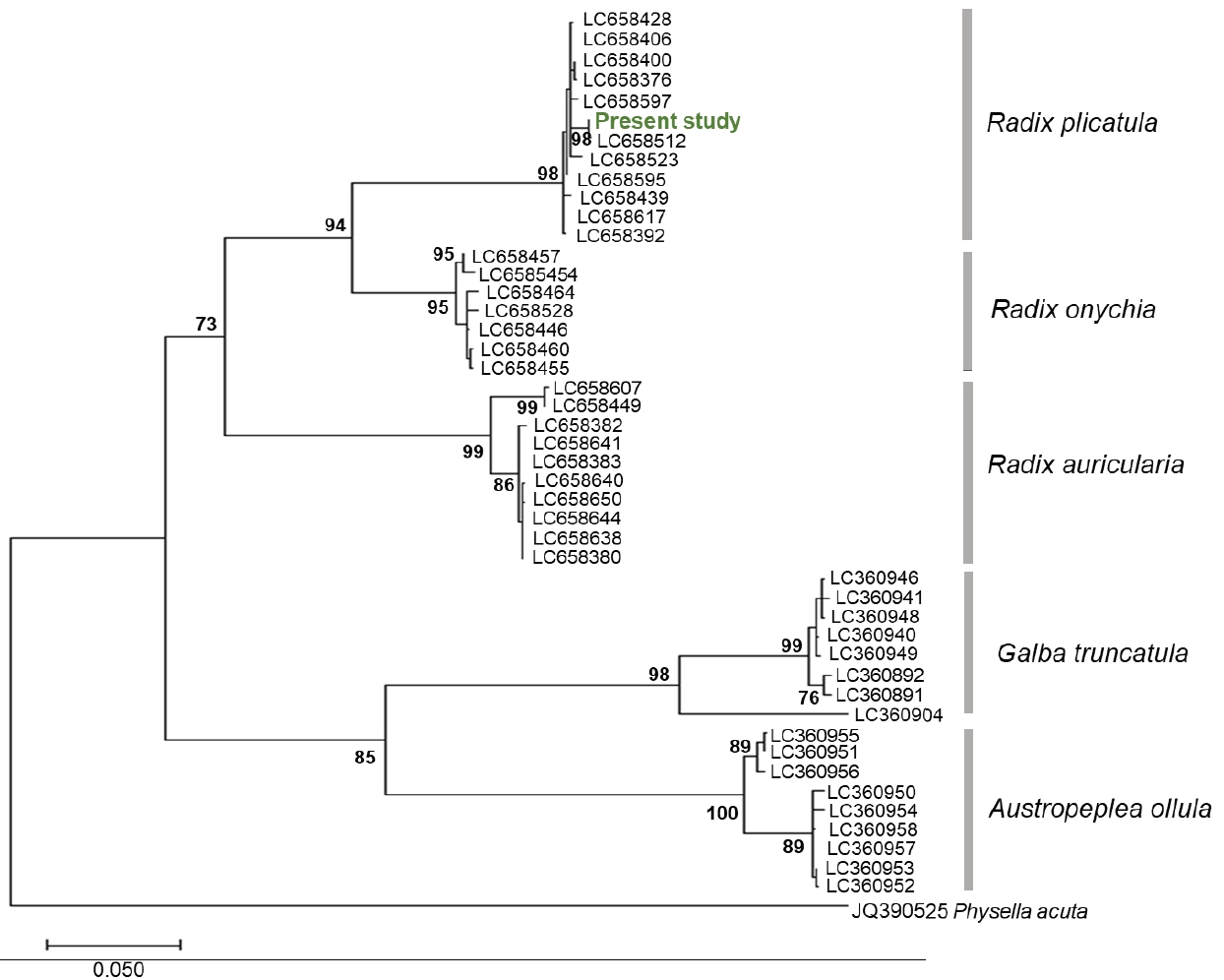

The lymnaeid snail

cox1 sequence was analyzed, and the length was determined as 660 bp. No sequence differences were detected among the snails examined. The lymnaeid snail sequence was submitted to GenBank under the accession number LC860983. The sequence was queried using the BLAST algorithm in the NCBI database and exhibited high similarity (99.9%) to the sequence from

Radix plicatula (LC658512) isolated in Ehime Prefecture, Japan. A phylogenetic tree based on the

cox1 gene was constructed using the nucleotide sequences of lymnaeid snails in the present study and those of 3

Radix species, together with sequences of

Galba truncatula and

Austropeplea ollula available from GenBank. The resulting constructed phylogenetic tree indicated that the snail specimens in this study grouped with

R. plicatula (

Fig. 4).

Discussion

The emergence of dermatitis contracted from the paddy field in Tokyo, Japan, in 2021 was attributed to skin invasion by the cercariae of

Trichobilharzia sp., with

R. plicatula as the intermediate host. This was based on the observed clinical symptoms and determination of the cercariae species found in resident snails. According to the Bureau of Environment of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government [

19], in urban areas, ecological network plans are often promoted to maintain and enhance the biodiversity of limited natural environments by preserving the remaining habitats and organically connecting them through “green” corridors and relay points. The paddy field at the present study site was located within a natural restoration area designed to integrate local greenery and riverine nature as part of the overall ecological network. The establishment of the life cycle of

Trichobilharzia in a restored natural environment provides evidence that an ecological relationship has been established between waterfowl and freshwater snails (

R. plicatula). Bird monitoring surveys have indicated that 2 waterfowl species, the spot-billed duck (

Anas sp.) and grey heron (

Ardea cinerea), have visited the paddy field annually since 2015. Given that members of the genus

Trichobilharzia are primarily transmitted to ducks, geese, or swans [

1], the spot-billed duck is the most likely definitive host. Furthermore, although drainage of paddy fields is important for maintaining an optimal environment for crop growth, this practice has not been implemented in the study site because it reportedly reduces the number of aquatic organisms inhabiting paddy fields [

20]. Therefore, it is considered that the reduction in the abundance of snails due to drainage did not occur. Based on the monthly temperature data from 2021 to 2023 in Tokyo (Japan Meteorological Agency,

https://www.data.jma.go.jp/stats/etrn/index.php), the average temperature for each month consistently exceeded 20°C from June to September every year. This temperature range is crucial, as Ozu et al. [

11] reported an increase in cercarial dermatitis when the mean temperature exceeds 20°C and stabilizes between 20°C and 25°C. Additionally, rising temperatures promote the development of the cercarial stage and cercarial emission rates, suggesting that even a slight temperature increase can increase transmission success [

5]. Given these findings and the results of this study, individuals working in the paddy field where the present case originated, should wear rubber boots and gloves from May to August to avoid skin exposure to water, particularly during the planting season (May to June).

Molecular analyses of the schistosome species revealed that the furcocercariae isolated in this study were most closely related to

Trichobilharzia sp. B isolated from American widgeons (

Anas americana) in the United States. In contrast, no species were grouped in the same phylogenetic position as the isolates identified in this study. The calculated p-distances between the

cox1 gene sequences of the furcocercariae in this study and

Trichobilharzia sp. B was 6.0%, which was lower than the interspecies values determined for other known species (7.2%–12.1%), but significantly greater than the intraspecies values (0.1%–2.2%). Previous studies have selected a p-distance >5% difference in COI or ND1 mtDNA markers as an indicator of separate species [

2,

21-

25]. Although the phylogenetic analysis results and p-distance values for

cox1 in the present study identified the isolated furcocercariae as

Trichobilharzia species, they were distinct from the species registered in the database. In Japan, the genus

Trichobilharzia was previously reported by at least 3 species:

T. physellae,

T. szidati, and

T. brevis [

26]. Of these, the nucleotide sequence of

T. brevis has not yet been registered in the database. Consequently, the molecular phylogenetic relationship between

T. brevis and the furcocercariae isolated in this study could not be verified. There is a scarcity of

Trichobilharzia sp. sequences in the GenBank DNA database; therefore, this poses a challenge for definitive molecular identification.

R. plicatula, which was infected with furcocercariae in this study, has been reported to be an intermediate host of

T. paoi, which is common across China [

27]. Based on the strong host specificity for certain intermediate host species of the genus

Trichobilharzia, it is possible that the infection in this study was caused by a species of

Trichobilharzia that has not yet been described in Japan.

Of the 3 species of

Trichobilharzia reported in Japan, neither

T. physellae nor

T. szidati has been reported as a cause of dermatitis since 1965. According to Suzuki et al. [

26], the absence of reports on dermatitis caused by these species has been attributed to a decline in the number of intermediate hosts,

R. auricularia, resulting from pesticide use or environmental changes in paddy fields. Conversely,

T. brevis utilizing

A. ollula as an intermediate host was reported as a new cause of dermatitis in Japan in the late 1960s [

11,

26,

28,

29]. Although subsequent outbreaks of cercarial dermatitis caused by

T. brevis have occurred in many parts of the country, reports of dermatitis caused by this species also declined dramatically in the 1990s. In Japan, cercarial dermatitis remains poorly recognized because a continuous epidemiological study on cercarial dermatitis has not been conducted for approximately 35 years. However, this does not necessarily mean that the disease is rare. This is because the symptoms are pathologically benign and are confused with other allergic reactions or insect bites [

30]. Meanwhile, recent studies have pointed out that changes in the populations of waterfowl and freshwater snails due to climate change may lead to the re-emergence of cercarial dermatitis [

31]. Indeed, an increase in the incidence of the disease has been noted, and cercarial dermatitis is now considered an emerging or re-emerging disease not only in Europe but also in the United States [

5,

30,

32].

Given these circumstances, our report on this zoonotic disease in Japan is highly significant, reaffirming its existence. Therefore, it is important to increase awareness of cercarial dermatitis through additional case reports, targeting not only agricultural workers but also environmental educators. Although paddy fields are semi-natural environments created for rice production, they perform some of the functions of natural wetlands and provide habitats and feeding sites for various organisms. Consequently, the government has encouraged environmental education to increase the understanding and awareness of biodiversity through rice cultivation [

33]; thus, paddy fields are also used as sites for environmental education for residents and children. As urban ecological restoration projects continue to expand, monitoring parasitic diseases at the wildlife-human interface is becoming increasingly important for public health management.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Banzai A, Sugiyama H. Data curation: Banzai A, Sugiyama H. Formal analysis: Banzai A. Investigation: Banzai A, Wada K, Katahira H, Hirasawa R. Project administration: Banzai A, Sugiyama H. Resources: Tanabe R, Saito S, Kobayashi K. Supervision: Sugiyama H. Validation: Banzai A, Katahira H. Writing – original draft: Banzai A.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kouzo Iwaki, Ecosystem Conservation Society-Japan, and Sae Hayashida, Azabu University, for their strong support and help in this investigation.

Fig. 1.The leg of the paddy field worker in the present case. Multiple erythematous papules appeared on the areas that had been submerged in paddy field water. Scale bar=5 cm.

Fig. 2.A furcocercaria isolated from an infected lymnaeid snail (live specimen). Scale bar=100 μm.

Fig. 3.Maximum-likelihood tree of Trichobilharzia species based on the sequence of the mtDNA cox1 gene. Bootstrap values >70 (percentage of 1,000 replicates) are shown at the branches. Schistosoma bovis (AY157212) was used as an outgroup.

Fig. 4.Maximum-likelihood tree of Radix spp., Galba truncatula and Austropeplea ollula, based on the sequence of the mtDNA cox1 gene. Bootstrap values >70 (percentage of 1,000 replicates) are shown at the branches. Physella acuta (JQ390525) was used as an outgroup.

Table 1.Prevalence of Trichobilharzia sp. cercariae in lymnaeid snails, Radix plicatula, by survey date

Table 1.

|

Date |

|

No. of snails |

|

Examined |

Infected |

% infected |

|

2021 |

Jul 22 |

53 |

1 |

1.9 |

|

Jul 30 |

62 |

5 |

8.1 |

|

Sep 15 |

68 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sep 28 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

2022 |

Apr 22 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

|

May 30 |

23 |

1 |

4.3 |

|

Jun 27 |

24 |

1 |

4.2 |

|

Jul 26 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Aug 30 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

2023 |

Apr 17 |

44 |

0 |

0 |

|

May 19 |

18 |

1 |

5.6 |

|

Jun 12 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

|

Jul 7 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Aug 9 |

25 |

2 |

8.0 |

|

Sep 8 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

|

Oct 6 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

|

413 |

11 |

2.7 |

Table 2.Mean uncorrected pairwise distance (p-distance, %) between Trichobilharzia species based on the sequence of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene

Table 2.

|

No. |

Species |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

1 |

Trichobilharzia querquedulae

|

1.3a

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Trichobilharzia physellae

|

9.1 |

0.1a

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

Trichobilharzia sp. A |

9.4 |

10.0 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

Trichobilharzia sp. B |

8.4 |

9.3 |

7.2 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

Trichobilharzia sp. C |

9.0 |

9.9 |

9.3 |

9.8 |

1.4a

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

Trichobilharzia franki

|

8.4 |

9.7 |

8.9 |

8.5 |

9.3 |

0.4a

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

Trichobilharzia regenti

|

12.0 |

11.4 |

10.6 |

9.5 |

11.5 |

11.0 |

2.2a

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

Trichobilharzia novaeseelandiae

|

11.6 |

10.5 |

9.8 |

10.5 |

12.1 |

11.3 |

8.0 |

0.2a

|

|

|

|

9 |

Trichobilharzia longicauda

|

8.2 |

9.2 |

8.3 |

9.5 |

10.0 |

9.3 |

10.3 |

10.4 |

- |

|

|

10 |

Present study |

7.3 |

9.3 |

7.5 |

6.0 |

9.8 |

9.3 |

11.4 |

10.1 |

10.2 |

- |

References

- 1. Horák P, Kolárová L, Adema CM. Biology of the schistosome genus Trichobilharzia. Adv Parasitol 2002;52:155-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-308x(02)52012-1

- 2. Brant SV, Loker ES. Molecular systematics of the avian schistosome genus Trichobilharzia (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae) in North America. J Parasitol 2009;95:941-63. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-1870.1

- 3. Horak P, Schets L, Kolarova L, Brant SV. Trichobilharzia. In Liu D ed, Molecular detection of human parasitic pathogen. CRC Press; 2012, pp 455-66.

- 4. Kolářová L, Horák P, Skírnisson K, Marečková H, Doenhoff M. Cercarial dermatitis, a neglected allergic disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2013;45:63-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-012-8334-y

- 5. Horák P, Mikeš L, Lichtenbergová L, et al. Avian schistosomes and outbreaks of cercarial dermatitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:165-90. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00043-14

- 6. Cort WW. Schistosome dermatitis in the United States (Michigan). J Am Med Assoc 1928;90:1027-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1928.02690400023010

- 7. Tanabe H. On the cause of Koganbyo. J Yonago Med Assoc 1948;1:2-3.

- 8. Cort WW. Studies on schistosome dermatitis. XI. Status of knowledge after more than 20 years. Am J Hyg 1950;52:251-307.

- 9. Rudolfová J, Hampl V, Bayssade-Dufour C, et al. Validity reassessment of Trichobilharzia species using Lymnaea stagnalis as the intermediate host. Parasitol Res 2005;95:79-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-004-1262-x

- 10. Oda T. Schistosome dermatitis in Japan. Prog Med Parasitol Jpn 1973;5:1-63.

- 11. Ozu S, Aida C, Takei S, Suzuki N, Ishizaki T. The paddy field dermatitis in Saitama Prefecture (I): epidemiological studies. J Jpn Assoc Rural Med 1972;21:361-7.

- 12. Blair D, Islam KS. The life cycle and morphology of Trichobilharzia australis n. sp. (Digenea: Schistosomatidae) from the nasal blood vessels of the black duck (Anas superciliosa) in Australia, with a review of the genus Trichobilharzia. Syst Parasitol 1983;5:89-117. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00049237

- 13. Podhorsky M, Huuzova Z, Mikes L, Horak P. Cercarial dimensions and surface structures as a tool for species determination of Trichobilharzia spp. Acta Parasitol 2009;54:28-36. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-009-0011-9

- 14. McPhail BA, Froelich K, Reimink RL, Hanington PC. Simplifying schistosome surveillance: using molecular cercariometry to detect and quantify cercariae in water. Pathogens 2022;11:565. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11050565

- 15. Sapp KK, Loker ES. Mechanisms underlying digenean-snail specificity: role of miracidial attachment and host plasma factors. J Parasitol 2000;86:1012-9. https://doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[1012:MUDSSR]2.0.CO;2

- 16. Olson PD, Cribb TH, Tkach VV, Bray RA, Littlewood DT. Phylogeny and classification of the Digenea (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda). Int J Parasitol 2003;33:733-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00049-3

- 17. Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrigenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 1994;3:294-9.

- 18. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018;35:1547-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096

- 19. Bureau of Environment of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo biodiversity strategy for 2030 [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.kankyo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/documents/d/english/Tokyo-Biodiversity-Strategy_en

- 20. Ichikawa N. The present condition and the preservation of pond insects lived in village. Jpn J Environ Entomol Zool 2008;19:47-50.

- 21. Vilas R, Criscione CD, Blouin MS. A comparison between mitochondrial DNA and the ribosomal internal transcribed regions in prospecting for cryptic species of platyhelminth parasites. Parasitology 2005;131:839-46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182005008437

- 22. Ebbs ET, Loker ES, Davis NE, et al. Schistosomes with wings: how host phylogeny and ecology shape the global distribution of Trichobilharzia querquedulae (Schistosomatidae). Int J Parasitol 2016;46:669-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.04.009

- 23. Fakhar M, Ghobaditara M, Brant SV, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of nasal avian schistosomes (Trichobilharzia) from aquatic birds in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Parasitol Int 2016;65:151-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2015.11.009

- 24. Laidemitt MR, Zawadzki ET, Brant SV, et al. Loads of trematodes: discovering hidden diversity of paramphistomoids in Kenyan ruminants. Parasitology 2017;144:131-47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182016001827

- 25. Davis NE, Blair D, Brant SV. Diversity of Trichobilharzia in New Zealand with a new species and a redescription, and their likely contribution to cercarial dermatitis. Parasitology 2022;149:380-95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182021001943

- 26. Suzuki N, Kawanaka M, Murata I, Ozu S. Recent paddy field dermatitis due to avian schistosome. Jpn Med J 1979;2890:43-6.

- 27. Attwood SW, Cottet M. Malacological and parasitological surveys along the Xe Bangfai and its tributaries in Khammouane Province, Lao PDR. Hydroecol Appl 2016;19:245-70. https://doi.org/10.1051/hydro/2015003

- 28. Suzuki N, Ozu S, Aida C, Takei S, Sawaura S. The paddy field dermatitis in Saitama Prefecture II: survey on the snails. J Jpn Assoc Rural Med 1973;484-90.

- 29. Suzuki N, Kawanaka M. Trichobilharzia brevis Basch, 1966, as a cause of an outbreak of cercarial dermatitis in Japan. Jpn J Parasitol 1980;29:1-11.

- 30. Kerr O, Juhász A, Jones S, Stothard JR. Human cercarial dermatitis (HCD) in the UK: an overlooked and under-reported nuisance? Parasit Vectors 2024;17:83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06176-x

- 31. Bispo MT, Calado M, Maurício IL, Ferreira PM, Belo S. Zoonotic threats: the (re)emergence of cercarial dermatitis, its dynamics, and impact in Europe. Pathogens 2024;13:282. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13040282

- 32. De Liberato C, Berrilli F, Bossù T, et al. Outbreak of swimmer’s itch in Central Italy: description, causative agent and preventive measures. Zoonoses Public Health 2019;66:377-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12570

- 33. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The biodiversity strategy of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2025 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/policies/env/env_policy/attach/pdf/biodivstrategy-6.pdf

, Hiromu Sugiyama1,2

, Hiromu Sugiyama1,2 , Kentaro Wada1

, Kentaro Wada1 , Hirotaka Katahira1

, Hirotaka Katahira1 , Rei Hirasawa1

, Rei Hirasawa1 , Ryota Tanabe3

, Ryota Tanabe3 , Sou Saito3

, Sou Saito3 , Kunitaka Kobayashi4

, Kunitaka Kobayashi4