Abstract

In this study, the trypsin gene (bgtryp-1) from the German cockroach, Blattella germanica, was cloned via the immunoscreening of patients with allergies to cockroaches. Nucleotide sequence analysis predicted an 863 bp open reading frame which encodes for 257 amino acids. The deduced amino acid sequence exhibited 42-57% homology with the serine protease from dust mites, and consisted of a conserved catalytic domain (GDSGGPLV). bgtryp-1 was determined by both Northern and Southern analysis to be a 0.9 kb, single-copy gene. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analyses of the recombinant protein (Bgtryp-1) over-expressed in Escherichia coli revealed that the molecular mass of the expressed protein was 35 kDa, and the expressed protein was capable of reacting with the sera of cockroach allergy patients. We also discussed the possibility that trypsin excreted by the digestive system of the German cockroach not only functions as an allergen, but also may perform a vital role in the activation of PAR-2.

-

Key words: Blattella germanica, trypsin, serine protease, allergen, PAR-2

INTRODUCTION

9 species of cockroach have been reported to exist in Korea (

Lee, 1967). However, only four species of household cockroach are commonly encountered. These include the German cockroach,

Blattella germanioa, the American cockroach,

Periplaneta americana, the Smoky-brown cockroach,

P. fuliginosa, and the House cockroach,

P. japonica. Among these four species, the German cockroach is the only one which constitutes a public health issue in Korea, due to its predominance in the region (

Lee et al., 2003).

Lee et al. (

1998) reported that cockroach antigen positivity was 11.4% in Korea, according to the results of a skin test study. This report also demonstrated that cockroach allergens constitute one of the most commonly encountered allergens in Korea, along with house dust mites, house dust, silk, and cat epithelial tissue.

The feces and whole body extracts of the cockroach have been shown to exhibit potent allergenicity (

Musmand et al., 1995). However, it has also been determined that the feces of the cockroach harbor a greater quantity of primary allergens than do the whole body extracts (

Yun et al., 2001;

Gore and Schal, 2005). These findings indicate that the compounds secreted from the digestive tract of the cockroach may potentially be the source of this potent allergenicity.

The notion that cockroach extract induces the activation of PAR-2 (protease-activated receptor 2) has been corroborated by several previous reports (

Kondo et al., 2004,

Hong et al., 2004). PAR-2 is a G-proteincoupled receptor, which can be activated by certain serine proteases, including trypsin and tryptase. PAR-2 is distributed extensively throughout the body, but is located abundantly within the gastrointestinal tract and the respiratory system (

Kawabata et al., 2002). PAR-2 appears to be activated by exposure to cockroach extract and mite allergens (serine proteases), resulting in the release of matrix metalloproteinase 9, inflammatory cytokine IL-8 (

Sun G, et al., 2001;

Page K, 2003), and an increase in the levels of Ca

++ (

Hong et al., 2004)

In this study, we report the full-length sequence of the trypsin gene from the digestive tract of the cockroach, which was identified via the immunoscreening of the B. germanica cDNA library. We also attempted to characterize the allergenicity of trypsin, as well as its potential PAR-2 activation effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cockroach

Adult male and female German cockroaches were reared for 24℃ on an artificial diet, and given free access to water.

cDNA library construction

A B. germanica cDNA library was constructed with Uni-ZAPTM XR expression vector (Stratagene, USA). In brief, the total RNA was isolated from 3 g of the midguts of adult B. germanica specimens. Following phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, poly(A+) RNA was purified with a Stratagene Poly(A) Quick mRNA Isolation Kit, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA synthesis of the isolated poly(A+) RNA was then conducted in 50 µl reaction volumes, using 50 units of MMLV-reverse transcriptase at 37℃ for 60 minutes. cDNA synthesis was primed using 5 µg oligo dT18. Second-strand synthesis was then conducted using RNase H and DNA polymerase I. After blunting the cDNA termini, we conducted EcoR I adaptor ligation and EcoR I phosphorylation. The region of the gel harboring the DNA molecules with lengths of less than 400 bp was then removed via Sepharose CL-2B gel filtration. The purified cDNA was ligated using dephosphorylated EcoR I Uni-ZAPTM XR vector arms, according to the manufacturer's instructions, then incubated using in vitro packaging extracts (Stratagene).

cDNA library Immunoscreening with the sera of B. germanica allergy patients

Ten serum samples were obtained from patients manifesting symptoms of perennial rhinitis, asthma, and eczema. These patients had been diagnosed with allergies, via RAST and skin prick tests. A set of control sera was acquired from 5 individuals, who were found not to be allergic to cockroaches, or to any other common allergens. The collection of sera for use in these studies was approved by the Human Subjects Investigation Committee of Kosin University. The library was screened using 1:10, 1:5, or 1:2 serum dilutions (pre-absorbed with Escherichia coli lysates) pooled from patients who had proven sensitive to B. germanica. Positive plaques were detected using alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-human IgE (1:500). The p-Bluescript phagemid harboring the cloned cDNA insert of the positive plaque was then excised from the Lambda Zap II vector, and was plated with fresh E. coli cells, in order to foster the formation of colonies (ExAssit/SOLR system: Stratagene). Doublestranded cDNA was then isolated and sequenced (Macrogen, DNA Sequencing Service, Seoul, Korea).

Plaque hybridization

The partial trypsin cDNA clone was subjected to plaque hybridization in order to generate full-length cDNA, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene).

Sequence analysis

Protein and nucleotide sequences were compared with the data from the nonredundant GenBank, EMBL, SwissProt, DBJ, GenPept, PDB, and PIR databases, using FASTA (GCG, Oxford Molecular Group, Inc). The sequence alignments were assessed using the GCG program.

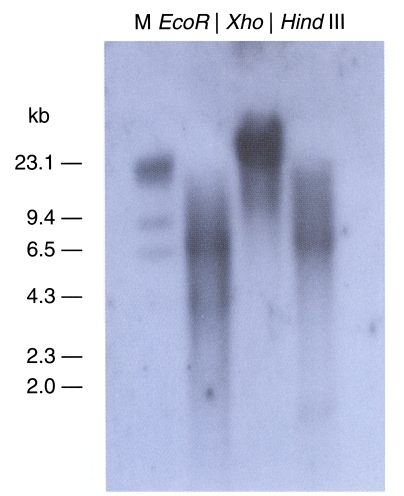

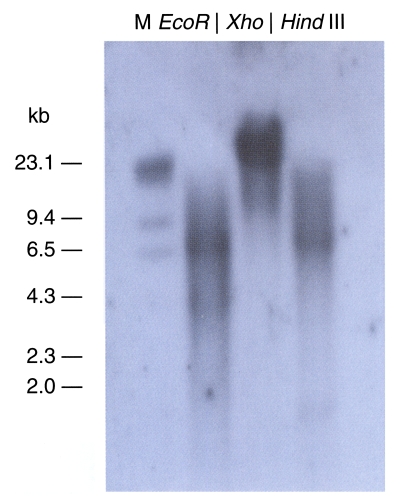

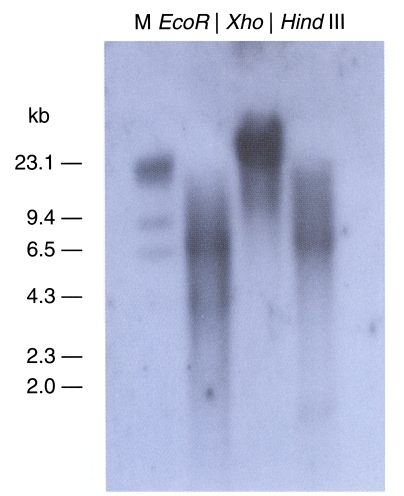

Southern blot analysis

10 µg of B. germanica genomic DNA was digested using 5 Units of EcoR I, Xho I, and Hind III (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). The DNA digests were separated on 0.8% agarose gel, then transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham, USA). The membranes were blocked and hybridized with [32p]cDNAlabeled probes prepared with a randomly primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). Prehybridization and hybridization were conducted at 60℃ with [32p]-labeled cDNA. After washing, the filters were air-dried, and exposed to X-ray film.

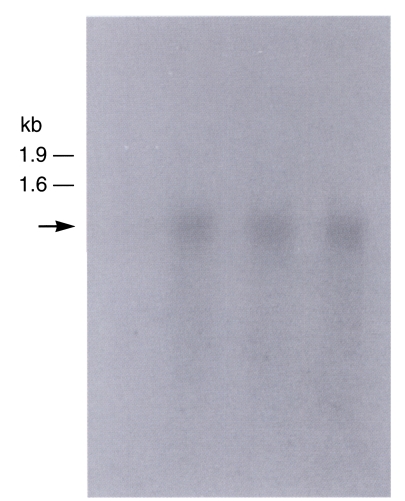

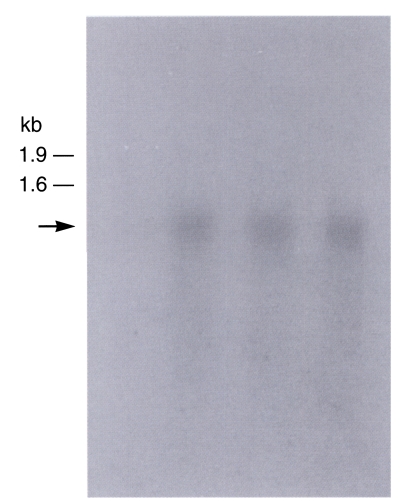

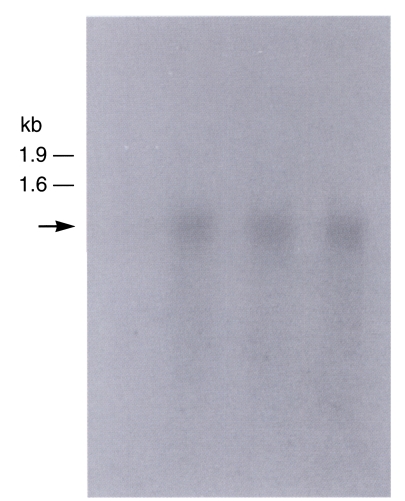

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the midgut tissues of adult cockroaches, as was described above. The RNA was separated on denaturing 1.0% agarose gel harboring 6.7% formaldehyde, then transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham, USA). The probe was constructed with the full-length trypsin gene, using the random prime labeling method (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany), and we conducted standard Northern hybridization analysis.

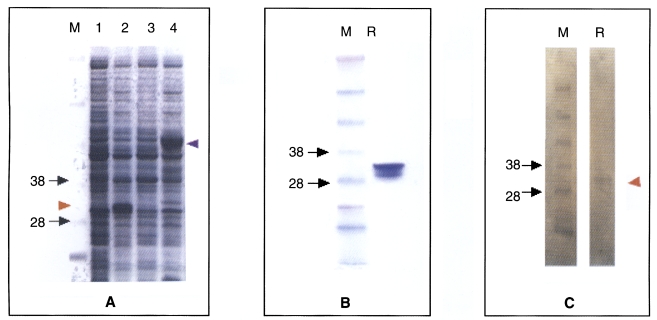

Expression and purification of recombinant trypsin

Trypsin-encoding cDNA was cloned into the pGEXKG expression vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 cells (DE3). Trypsin-encoded cDNA was then transferred to pGEX-KG as a BamH I-EcoR I fragment. Competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were allowed to grow to an O.D. 600 of 0.6 in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 200 µg/ml of ampicillin. Isopropylthio-β-galactoside was then added to a final concentration of 0.6 mM, and incubation proceeded for an additional 3 hours. An uninduced control culture was also prepared without IPTG. The cells were harvested via centrifugation, and the pellets were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA, harboring 100 µg/ml of lysozymes, then incubated for 15 minutes at 37℃. After mild sonication (six pulses of 10 seconds each), the recombinant trypsin, which was Glutathione S-transferase fusion protein in the E. coli, was induced 0.3 mM IPTG at 37℃, 3 h. The harvested cells were washed in cold PBS, after which we added ice-cold lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT) containing 200 µg/ml of lysozymes. Both the induced and control bacteria were then pelleted and frozen at -20℃ until use. After sonication, the centrifuged supernatants were added to 2 ml glutathione-affinity resin, and cultured at 4℃, for 30 minutes. The supernatant was again washed with 10 volume thrombin digestion buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) and 20 µg thrombin was added (Sigma, USA). After protein retrieval, the proteins were further concentrated using Centriprep 10 and Centricon 10 (Millipore USA). The concentrated proteins were then diluted using a 4 volume of equilibration buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT). The released fractions were collected and applied to a gel filtration column, in order to purify the trypsin to homogeneity.

Western blot analysis

The IPTG-induced and uninduced BL21/trypsin bacterial lysates were boiled in SDS sample buffer supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol. The constituent proteins were then fractionated via SDSPAGE, and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (pore size, 0.45 µm: Millipore USA). After being electrophoretically transferred, the membranes were blocked for 1 hour with 5% skim milk in PBST. The blots were washed 3 times with PBST, and then stored at 4℃ in the sera of the cockroach allergy patients overnight. After 3 times washings with PBST, the membranes were reincubated with horseradish peroxidase-labelled goat anti-human IgE (Dako, Denmark) diluted to 1:500 in PBST-BSA for 2 hours at room temperature. The membranes were then developed using DAB (Sigma, diaminobenzidine 6 mg, 50 mM tris-HCl, pH 6.7 9 ml, 0.3% nickel chloride 1 ml, hydrogen peroxide 10 µl).

RESULTS

Construction of the cDNA library from the B. germanica digestive tract

After the construction of the cDNA library, the mean size of the inserts was determined to be 0.3-2.0 Kb, and the titer of the cDNA library was measured at 1012 pfu/ml.

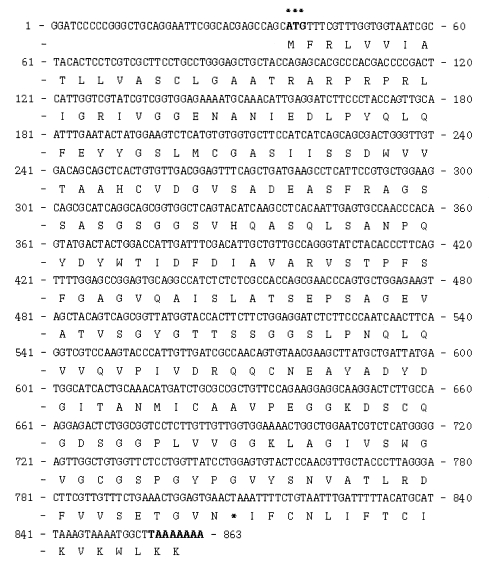

Characterization of B. germanica trypsin

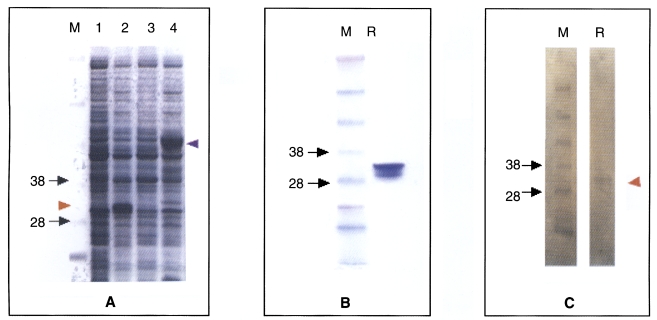

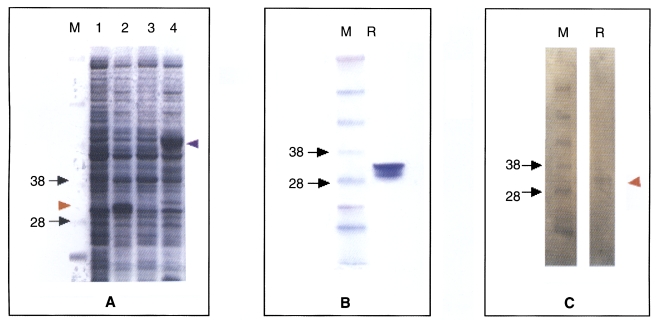

The immunoscreening of the cDNA library with the German cockroach allergy patients revealed a partial trypsin clone. In order to generate the full-length cDNA sequence of this trypsin, we conducted a plaque hybridization of the

B. germanica cDNA library, using the cDNA fragment as a probe. The largest insert exhibited a single open reading frame of 863 bp, which predicted the formation of a protein which was composed of 257 amino acid residues (

Fig. 1,

bgtryp-1). At the 3' end of

bgtryp-1, we noted a translation termination codon, followed by 45 nucleotides of a presumably untranslated sequence, and a poly(A) tail (GenBank accession number DQ149980). On the basis of the BLASTP homology searches, the deduced amino acid sequences of the cloned genes were clearly determined to belong to a trypsin-like protease.

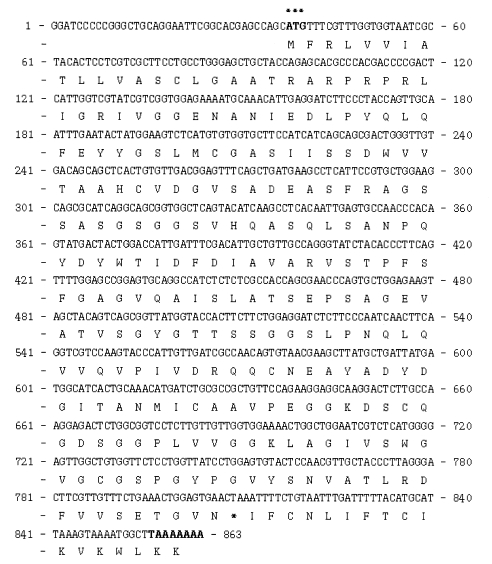

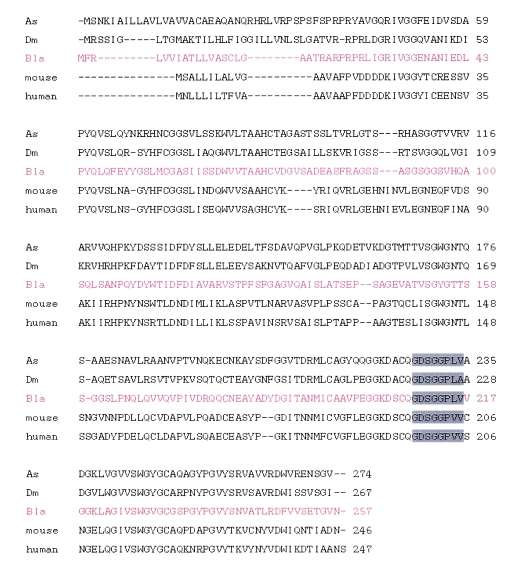

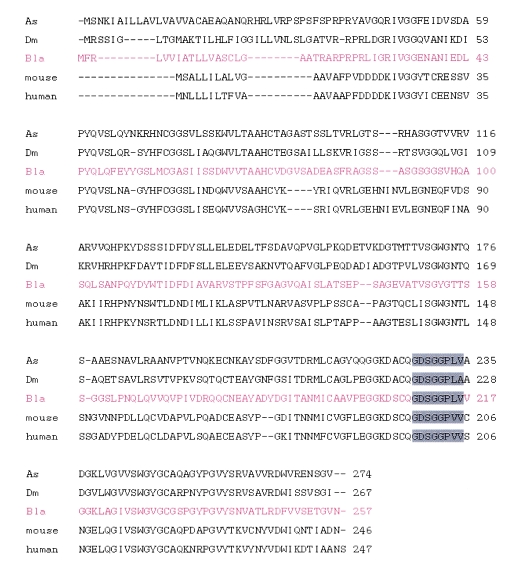

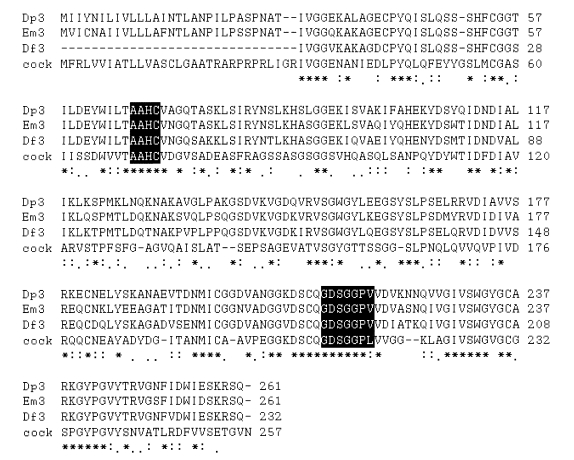

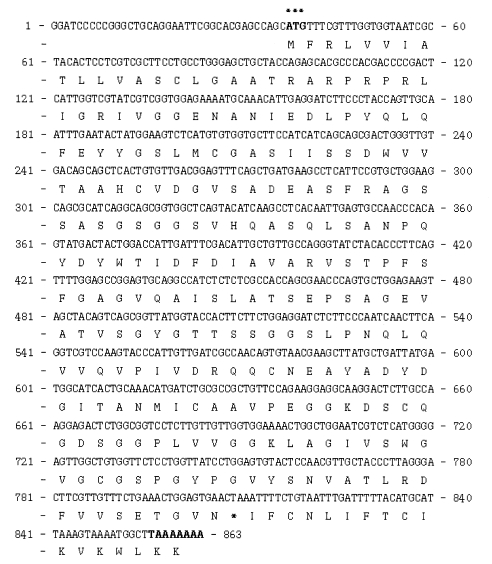

bgtryp-1 exhibited 40% and 35-37% similarity with insect trypsin genes and mammalian trypsin genes, respectively (

Fig. 2). It was also 42-57% similar in sequence to several mite serine protease allergens, including

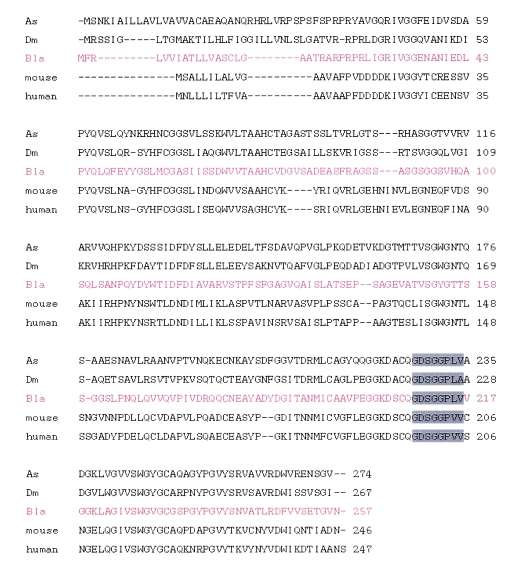

Der f 3 (

Dermatophagoides farinae), Eur m 3 (

Euroglyphus maynei),

Der p 3 (

Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus), and the fully-conserved catalytic domain, GDSGGPLV (

Fig. 3).

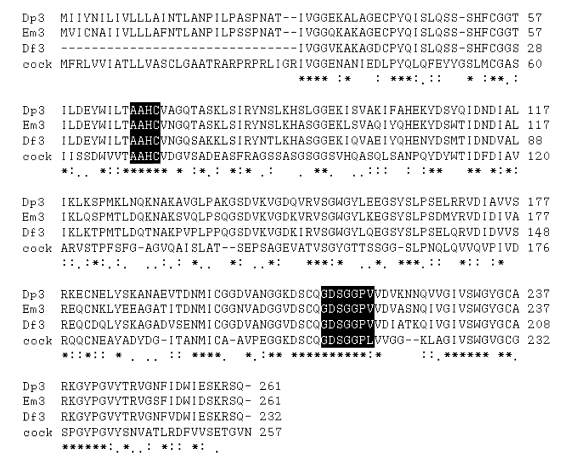

The genomic DNA from the cockroach was separated and digested using 3 kinds of enzymes, all of which lacked target sites in the gene. A cDNA probe of approximately 500 bp was used in our Southern blot hybridization (

Fig. 4). The observation of only one band indicated that this clone was a single-copy gene. The Northern blot evidenced a 0.9 kb transcript (

Fig, 5).

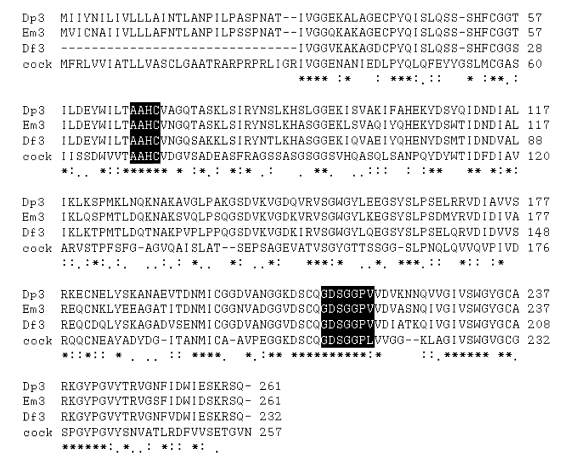

Expression of the recombinant proteins in

E. coli BL21, resulted in high level of

B. germanica trypsin protein (Bgtryp-1) visualized by Coomassie Blue staining of whole bacterial lysates separated by SDSPAGE. Thick band of expected sizes of fusion protein with GST (glutathione-S-transferase) was calculated as 49 kDa (

Fig. 6A lane 4) and 35 kDa when the signal was detached by thrombin (

Fig. 6A lane 2 and

Fig. 6B). The proteins expressed were contained in soluble fraction of the bacterial lysates. After purification of the fusion proteins, bands were confirmed to be located at their respective expected sizes. The recombinant protein detached signal reacted with sera positive to cockroach allergen at 35 kDa level (

Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

Trypsin and trypsinogen are most frequently encountered among insect serine peptidases. The primary function of these proteolytic enzymes is digestion, but they persist in the excreta of the insects (

Graf et al., 1986;

Fitches and Gatehouse, 1998;

Jordao et al., 1999). The cockroach is an especially omnivorous animal, and the midgut of the cockroach harbors many enzymes, including proteases. A trypsin-like proteinase which breaks down proteins into peptones and polypeptides is known to be generated in the midgut of the cockroach. Trypsin and chymotrypsin are the most frequently encountered of the serine endopeptidases, and protease activity has been confirmed in the cockroach (

Lopes and Terra, 2003).

In order to characterize these cockroach-harbored allergens, we extracted mRNA from adult cockroaches, and used RT-PCR to convert the cDNA in the construction of a cDNA library. Sera collected from patients with cockroach allergies were then applied to the cDNA library, in order to discover the allergen genes. The gene which was determined to have reacted with the sera of the cockroach allergy patients was the trypsin molecule, which is 863 bp in length, and contained a deduced 257 amino acids (

Fig. 1). In order to confirm the allergenicity of the cockroach trypsin gene, we expressed the recombinant trypsin in an

E. coli. The recombinant trypsin protein expressed in the

E. coli was also demonstrated to react with the sera of the cockroach allergy patients.

The serine proteases of house dust mites have already been reported to be one of the most important inhaled allergens (

Thomas et al., 2002;

Plattis-Mills et al., 1992). Previously, Ando et al., (

1993) purified a trypsin-like protease from an extract of mite feces. This group concluded that the trypsin-like protease isolated in the from mite fecal extract was actually the

Der f 3 allergen, and determined that the protease may be involved in the digestive process of the mite, because it was found in the mite feces, but not in the mite's body.

There is a growing body of evidence to support the notion that the stimulation of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) may contribute to the onset and progression of airway inflammatory diseases, including asthma and allergies (

Knight et al., 2001,

Kondo et al., 2004). Sun et al., (

2001) reported that both the

Der p 3 and

Der p 9 antigens are quite likely to interact with the PAR-2 expressed in pulmonary epithelial cells, and to induce the release of the proinflammatory cytokines, GM-CSF and eotaxin. Both the

Der p 3 and

Der p 9 antigens are members of the serine protease family. As was determined in conjunction with the house dust mite serine protease, the trypsin we screened in this study appears to have serious potential to activate the PAR-2 receptor. Kondo et al. (

2004) demonstrated that a cockroach extract contained component(s) capable of inducing a calcium transient and ERK phosphorylation in mouse lung fibroblast cells, which occurred in a PAR-2 expression-dependent manner. Kondo et al. also suggested that this activity could be attributed to a protease, due to its sensitivity to heat denaturation and PMSF (phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride). However, until now, this cockroachharbored serine protease allergen remained to be identified.

It has been hypothesized that chronic exposure to dust allergens may constitute an important trigger for acute allergic attacks, as the majority of patients who are allergic to dust mites do not recognize the relationship existing between exposure to house dust and acute asthma attacks (

Platts-Mills et al., 1992). Recent studies have shown that proteases derived from the serine protease allergens associated with house dust mites (

Der p 3 and

Der p 9), as well as cysteine protease

Der p 1, directly stimulate bronchial epithelial cells via a non-allergic mechanism, through the activation of PAR-2 (

Sun et al., 2001;

Asokananthan et al., 2002). These results help to explain the dual mechanism exploited by such allergens, which is characterized by PAR-2 activation and allergic reaction.

Gore and Schal (

2004) reported that, among the allergens associated with the cockroach, the

Bla g 1 is the one which predominates in the midgut of the cockroach, and the

Bla g 1 gene is expressed exclusively by the cells in the midgut. Also, adult female cockroaches produce and excrete significantly more

Bla g 1 in their feces than do males or nymphs, suggesting that the female adults of the species process more food than do any other German cockroaches. In addition, Gore and Schal (

2005) confirmed that excretion of

Bla g 1 in the feces varies according to food intake. This report also supports the prediction that trypsin would be secreted in the feces of cockroaches, where they would function as inhalant allergens, and activate PAR-2 within the respiratory tracts of humans.

The results of the present study demonstrate that trypsin (bgtryp-1) secreted from the alimentary canal of the cockroach can induce allergic reactions, and that the mechanisms underlying its activities can be attributed to PAR-2 activation.

Notes

-

This study was supported by the Korean Research Foundation grant (R04-2001-000-00269-0)

References

- 1. Ando T, Homma R, Ino Y, Ito G, Miyahara A, Yanagihara T, Kimura H, Ikeda S, Yamakawa H, Iwaki M, et al. Trypsin-like protease of mites: purification and characterization of trypsin-like protease from mite faecal extract Dermatophagoides farinae. Relationship between trypsin-like protease and Der f III. Clin Exp Allergy 1993;23:777-784.

- 2. Asokananthan N, Graham PT, Stewart DJ, Bakker AJ, Eidne KA, Thompson PJ, Stewart GA. House dust mite allergens induce proinflammatory cytokines from respiratory epithelial cells: the cysteine protease allergen, Der p 1, activates protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2 and inactivates PAR-1. J Immunol 2002;169:4572-4578.

- 3. Bernton HS, Brown H. Preliminary studies of the cockroach. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1964;35:506-513.

- 4. Bernton HS, Brown H. Insect allergy: The allergenicityof the excrement of the cockroach. Ann Allergy 1970;28:543-547.

- 5. Bernton HS, McMahon TF, Brown H. Cockroach asthma. Br J Chest 1972;66:61-66.

- 6. Fitches E, Gatehouse JA. A comparison of the short and long term effects of insecticidal lectins on the activities of soluble and brush border enzymes of tomato moth larvae (Lacanobia oleracea). J Insect Physiol 1998;44:1213-1224.

- 7. Graf R, Raikhel AS, Brown MR, Lea AO, Briegel H. Mosquito trypsin: immunochytochemical localization in the midgut of blood-fed Aedes aegypti (L.). Cell Tissue Res 1986;245:19-27.

- 8. Gore JC, Schal C. Gene expression and tissue distribution of the major human allergen Bla g 1 in the German cockroach, Blattella germanica L. (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae). J Med Entomol 2004;41:953-960.

- 9. Gore JC, Schal C. Expression, production and excretion of Bla g 1, a major human allergen, in relation to food intake in the German cockroach, Blattella germanica. Med Vet Entomol 2005;19:127-134.

- 10. Hong JH, Lee S, Kim K, Yong T, Sohn MH, Shin DM. German cockroach extract activates protease-activated receptor 2 in human airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:315-319.

- 11. Jordao BP, Capella AN, Terra WR, Ribeiro AF, Ferreira C. Nature of the anchors of membrane-bound aminopeptidase, amylase, and trypsin and secretory mechanisms in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera) midgut cells. J Insect Physiolo 1999;45:29-37.

- 12. Kang B, Sulit N. A comparative study of prevalence of skin hypersensitivity to cockroach and house dust antigens. Ann Allergy 1978;41:333-336.

- 13. Kang B, Vellody D, Homburger H, Yunginger JW. Cockroach cause of allergic asthma: its specificity of immunologic profiles. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1979;63:80-86.

- 14. Kawabata A, Kuroda R, Nishida M, Nagata N, Sakaguchi Y, Kawao N, Nishikawa H, Arizono N, Kawai K. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) in the pancreas and parotid gland: Immunolocalization and involvement of nitric oxide in the evoked amylase secretion. Life Sci 2002;71:2435-2446.

- 15. Knight DA, Lim S, Scaffidi AK, Roche N, Chung KF, Stewart GA, Thompson PJ. Protease-activated receptors in human airways: upregulation of PAR-2 in respiratory epithelium from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:797-803.

- 16. Kondo S, Helin H, Shichijo M, Bacon KB. Cockroach allergen extract stimulates protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) expressed in mouse lung fibroblast. Inflamm Res 2004;53:489-496.

- 17. Lee CE. Tentative list of Korean cockroaches (Blattaria). Kyungpook Univ Theses Coll 1967;11:179-184.

- 18. Lee DK, Lee WJ, Sim JK. Population densities of cockroaches from huma dwellings in urban areas in the Republic of Korea. J Vector Ecol 2003;28:90-96.

- 19. Lee SY, Kim DS, Kim KE, Jeaung BJ, Lee KY. IgE binding patterns to german cockroach whole body extract in Korea atopic asthma children. Yonsei Med J 1998;39:409-416.

- 20. Lopes AR, Terra WR. Purification, properties and substrate specificity of a digestive trypsin from Periplaneta americana (Dictyoptera) adults. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2003;33:407-415.

- 21. Musmand JJ, Horner WE, Lopez M, Lehrer SB. Identification of important allergens in German cockroach extracts by sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacry-lamide gel electrophoresis and western blot analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:877-885.

- 22. Page K, Strunk VS, Hershenson MB. Cockroach proteases increase IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells via activation of protease-activated receptor (PAR-2) and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:1112-1118.

- 23. Platts-Mills TA, Thomas WR, Aalberse RC, Vervloet D, Chapman MD. Dust mite allergens and asthma: report of a second international workshop. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992;89:1046-1060.

- 24. Richman PG, Khan HA, Turkeltaub PC, Malveaux FJ, Baer H. The important sources of German cockroach allergens as determined by RAST analyses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1984;73:590-595.

- 25. Sun G, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Interactionof mite allergens Der p 3 and Der p 9 with protease-Activated Receptor-2 expressed by lung epithelial cells. J Immunol 2001;167:1014-1021.

- 26. Thomas WR, Smith WA, Hales BJ, Mills KL, O'Brien RM. Characterization and immunobiology of house dust mite allergens. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2002;129:1-18.

- 27. Yun YY, Ko SW, Park JW, Lee IY, Ree HI, Hong CS. Comparison of allergic components between German cockroach whole body and fecal extracts. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2001;86:551-556.

Fig. 1Complete nucleotide and the deduced amino acid sequence of cockroach trypsin (bgtryp-1). The trypsin was consisted of 863 nucleotides and 257 amino acids The initiation methionine and the stop codon TAA are shown (*).

Fig. 2Similarity comparison of B. germanica trypsin gene (bgtryp-1) with different trypsins: African malaria vector mosquito (Anopheles gambiae, As), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), mouse and human. The cloned cockroach serine protease had 40% homology with insect trypsin, 35-37% with mammalian trypsin.

Fig. 3Multiple alignment of amino acid sequence of B. germanica trypsin (bgtryp-1) and other mite serine protease group 3 allergen. B. germanica trypsin showed 42-57% sequence identity with other mite serine protease allergens, Der f 3 (Dermatophagoides farinae, gi/1314736), Eur m 3 (Euroglyphus maynei, gi/4204421), Der p 3 (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, sp/P39675).

Fig. 4Southern hybridization analysis of B. germanica DNA using a 32P-labelled trypsin gene (bgtryp-1) as a probe. Genomic DNA sample were digested with EcoR I, Xho I, Hind III restriction enzyme. The gene was shown as a single copy gene. Size marker on the left were from lambda DNA digested with Hind III.

Fig. 5Autoradiographs of Northern blots with B. germanica trypsin (bgtryp-1). Total RNA was separated on 1.0% agarose gel containing 6.7% formaldehyde. RNA was transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membrane, probed with cDNA inserts of B. germanica trypsin (bgtryp-1). Transcript size was approximately 0.9 kb.

Fig. 6SDS-PAGE analysis (A and B) and western blot (C) of recombinant trypsin (Bgtryp-1). A. not induced (lane 1), IPTG-induced, signal detached protein (lane 2). pGEX with trypsin encoding cDNA, not IPTG-induced (lane 3), induced (lane 4), Band is observed in 49 KDa level (purple arrow head). B. purified recombinant protein. C. Recombinant trypsin (Bgtryp-1) is blotted with cockroach allergic sera. Band is observed in 35 KDa level (red arrow head). M; marker, R; recombinant protein