Abstract

Neospora caninum is an important cause of abortion in cattle, and dogs are its only known definitive host. Its seroprevalence among domestic urban and rural dogs and feral raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides koreensis) in Korea was studied by indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT) and by the neospora agglutination test (NAT), respectively. Antibodies to N. caninum were found in 8.3% of urban dogs and in 21.6% of dogs at dairy farms. Antibody titers ranged from 1:50 to 1:400. Antibodies to N. caninum were found in six (23%) of 26 raccoon dogs. However, the potential role of raccoon dogs as a source of horizontal transmission of bovine neosporosis needs further investigation. The results of this study suggest that there is a close relationship between N. caninum infection among dairy farm dogs and cattle in Korea. This study reports for the first time upon the seroprevalence of N. caninum infection in raccoon dogs in Korea.

-

Key words: Neospora caninum, Dogs, raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides koreensis)

Neospora caninum is now recognized as one of the most important causes of bovine abortion in many countries (

Dubey, 2003). Bovine neosporosis has also been reported in Korea (

Kim et al., 1997;

Hur et al., 1998); the parasite has been isolated from the tissues of an aborted bovine fetus and congenitally infected calf (

Kim et al., 2000). A nation-wide survey also revealed that approximately 21.1% of bovine abortions in Korea are caused by

N. caninum (

Kim et al., 2002). Both vertical (transfer of the parasite from a dam to the fetus) and horizontal (ingestion of the oocysts shed by a definite host) transmissions of

N. caninum occur in cattle, and the domestic dog is the only known definitive host (

McAllister et al., 1998;

Basso et al., 2001b). The precise route of

N. caninum transmission to dogs is not yet fully understood, and possibility that other mammals act as natural hosts has not been explored. Relatively few studies on the prevalence of

N. caninum antibodies in wild animal populations have been reported.

N. caninum antibody has been found in coyotes, foxes, dingoes, and raccoons (

Dubey, 2003). The present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of antibodies to

N. caninum in dogs (urban and rural) and in raccoon dogs (

Nyctereutes procyonoides koreensis) in Korea.

Serum samples were obtained from 340 (289 urban and 51 rural) domestic dogs and 26 Korean raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides koreensis). The urban dogs were from local veterinary hospitals, and were 2 to 7 years old, with a mean age of 5 years. Serum samples from 51 dogs kept at dairy farms, which had experienced bovine neosporosis, were also collected. The raccoon dogs were collected as a part of national rabies surveillance project.

Sera from domestic dogs were examined by indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT). IFAT was performed on

N. caninum as described by Hur et al. (

1998) using the KBA-1 isolate of

N. caninum as antigen and a cutoff titer of 1:50. Antibody titers higher than 1:50 were decided to be seropositive only when complete peripheral tachyzoite fluorescence was noted. Sera from raccoon dogs were tested by the neopsora agglutination test (NAT), which was performed as described by Romand et al. (

1998) using a cut-off titer of 1 : 512 and commercially available reagents.

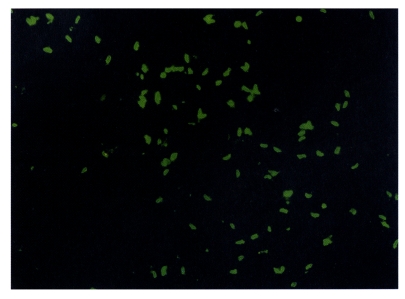

Antibodies to

N. caninum were found in 8.3% of urban dogs and in 21.6% of dogs from dairy farms (

Table 1 and

Fig. 1). Antibody titers ranged from 1:50 to 1:400. Of the 35 seropositive cases, 16 were male, 10 were female, and the remainder unknown. Antibodies to

N. caninum were found in 6 (23%) of the 26 raccoon dogs.

The seroprevalence of urban dogs to

N. caninum was 8.3%, which is similar to the results of serological surveys performed in Japan; 7% of 198 dogs (

Sawada et al., 1998), in 35 USA states and 3 Canadian provinces; 7% of 1,077 dogs (

Cheadle et al., 1999), and in Brazil; 6.7% of 163 dogs (

Mineo et al., 2001). However, the prevalence of antibodies to

N. caninum in dogs kept at dairy farms that had experienced bovine abortions caused by

N. caninum infections was approximately 3 times higher than that in urban dogs (p < 0.05). These findings on the seroprevalence of

N. caninum are similar to those in urban and rural dogs in Japan (

Sawada et al., 1998), the Netherlands (

Wouda et al., 1999), and Argentina (

Basso et al., 2001a). Moreover, epidemiologic investigations have reported a positive relationship between

Neospora caninum infection in cattle and dog (

Sawada et al., 1998;

Wouda et al., 1999). We suspect that horizontal transmission of neosporosis between cattle and dogs may be occurring at affected farms.

It is interesting that 23% of raccoon dogs were found to have

N. caninum antibodies, as this suggests that they act as a natural host for

N. caninum. Lindsay et al. (

2001) reported

N. caninum antibodies in 10% of 99 raccoons from Florida, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts in USA. In Korea, raccoon dogs are frequently observed near dairy farms and have free access to the farms (

So et al., 2002). Whether these dogs can excrete

N. caninum oocysts needs further investigation. However, as the number of raccoon dogs used in the present study was small, the role that raccoon dogs may transmitting

N. caninum to cows remains unknown. This study is the first to report upon the seroprevalence of

N. caninum infection in raccoon dogs in Korea.

Notes

-

This study was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (399002-3) and by the Brain Korea 21 project.

References

- 1. Basso W, Venturini L, Venturini MC, et al. Prevalence of Neospora caninum infection in dogs from Beef-cattle farms, dairy Farms, and from urban areas of Argentina. J Parasitol 2001a;87:906-907.

- 2. Basso W, Venturini L, Venturini MC, et al. First isolation of Neospora caninum from the feces of a naturally infected dog. J Parasitol 2001b;87:612-618.

- 3. Cheadle MA, Lindsay DS, Blagburn BL. Prevalence of antibodies to Neospora caninum in dogs. Vet Parasitol 1999;85:325-330.

- 4. Dubey JP. Review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis in animals. Korean J Parasitol 2003;41:1-16.

- 5. Hur K, Kim JH, Hwang WS, et al. Seroepidemiological study of Neospora caninum in Korean dairy cattle by indirect immunofluorescent antibody assay. Kor J Vet Res 1998;38:859-866.

- 6. Kim DY, Hwang WS, Kim JH, et al. Bovine abortionassociated with Neospora in Korea. Kor J Vet Res 1997;37:607-612.

- 7. Kim JH, Sohn HJ, Hwang WS, et al. In vitro isolation and characterization of bovine Neospora caninum in Korea. Vet Parasitol 2000;90:147-154.

- 8. Kim JH, Lee JK, Lee BC, et al. Diagnostic survey of bovine abortion in Korea: with special emphasis on Neospora caninum. J Vet Med Sci 2002;64:1123-1127.

- 9. Lindsay DS, Spencer J, Rupprecht C, Blagburn BL. Prevalence of agglutinating antibodies to Neospora caninum in raccoons, Procyon Iotor. J Parasitol 2001;87:1197-1198.

- 10. McAllister MM, Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Jolley WR, Wills RA, McGuire AM. Dogs are definitive hosts of Neospora caninum. Int J Parasitol 1998;28:1473-1478.

- 11. Mineo TW, Silva DA, Costa GH, et al. Detection of IgG antibodies to Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in dogs examined in a veterinary hospital from Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2001;98:239-245.

- 12. Romand S, Thulliez P, Dubey JP. Direct agglutination test for serologic diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection. Parasitol Res 1998;84:50-53.

- 13. Sawada M, Park CH, Kondo H, et al. Serological survey of antibody to Neospora caninum in Japanese dogs. J Vet Med Sci 1998;60:853-854.

- 14. So BJ, Jean YH, Lee SK, et al. First field trial of rabies bait vaccines in the republic of Korea. Kor J Vet Publ Hlth 2002;26:121-134.

- 15. Wouda W, Dijkstra T, Kramer AM, van Maanen C, Brinkhof JM. Seroepidemiological evidence for relationship between Neospora caninum infection in dogs and cattle. Int J Parasitol 1999;29:1677-1682.

Fig. 1Note positive titer with complete peripheral immunofluorescence of canine sera on IFAT (X 40).

Table 1.Prevalence of antibodies to Neospora caninum in dogs from urban and rural areas in Korea

Table 1.

|

Dog type |

No. tested |

No. Positive (%) |

Antibody titers

|

|

50 |

100 |

200 |

400 |

800 |

|

Urban |

289 |

24 (8.3) |

15 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

Rural |

51 |

11 (21.6) |

6 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- First description of Hepatozoon canis in raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides)

Itainara Taili, Jongseung Kim, Sungryong Kim, Dong-Hyuk Jeong, Ki-Jeong Na

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife.2025; 28: 101132. CrossRef - Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum Infection in Dog Population Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Davood Anvari, Reza Saberi, Mehdi Sharif, Shahabbedin Sarvi, Seyed Abdollah Hosseini, Mahmood Moosazadeh, Zahra Hosseininejad, Tooran Nayeri Chegeni, Ahmad Daryani

Acta Parasitologica.2020; 65(2): 273. CrossRef - First report of Neospora caninum seroprevalence in farmed raccoon dogs in China

Lan-Bi Nie, Yang Zou, Jun-Ling Hou, Qin-Li Liang, Wei Cong, Xing-Quan Zhu

Acta Tropica.2019; 190: 80. CrossRef - RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC LITERATURE, 1990–2015, ON WILDLIFE-ASSOCIATED DISEASES FROM THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA

Jusun Hwang, Kyunglee Lee, Young-Jun Kim, Jonathan M. Sleeman, Hang Lee

Journal of Wildlife Diseases.2017; 53(1): 5. CrossRef - A review of neosporosis and pathologic findings of Neospora caninum infection in wildlife

Shannon L. Donahoe, Scott A. Lindsay, Mark Krockenberger, David Phalen, Jan Šlapeta

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife.2015; 4(2): 216. CrossRef - The biological potential of the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides, Gray 1834) as an invasive species in Europe—new risks for disease spread?

Astrid Sutor, Sabine Schwarz, Franz Josef Conraths

Acta Theriologica.2014; 59(1): 49. CrossRef - Control options forNeospora caninum– is there anything new or are we going backwards?

MICHAEL P. REICHEL, MILTON M. McALLISTER, WILLIAM E. POMROY, CARLOS CAMPERO, LUIS M. ORTEGA-MORA, JOHN T. ELLIS

Parasitology.2014; 141(11): 1455. CrossRef - Evidence of Neospora caninum exposure among native Korean goats (Capra hircus coreanae)

B.Y. Jung, S.H. Lee, D. Kwak

Veterinární medicína.2014; 59(12): 637. CrossRef - Neospora caninumand Wildlife

Sonia Almería

ISRN Parasitology.2013; 2013: 1. CrossRef - Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in dogs from Korea

Thuy Nguyen, Se-Eun Choe, Jae-Won Byun, Hong-Bum Koh, Hee-Soo Lee, Seung-Won Kang

Acta Parasitologica.2012;[Epub] CrossRef - Occurrence of antibodies to Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in dogs from Pernambuco, Northeast Brazil

Luciana Aguiar Figueredo, Filipe Dantas-Torres, Eduardo Bento de Faria, Luis Fernando Pita Gondim, Lucilene Simões-Mattos, Sinval Pinto Brandão-Filho, Rinaldo Aparecido Mota

Veterinary Parasitology.2008; 157(1-2): 9. CrossRef - Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dogs in south-western Poland

Katarzyna Płoneczka, Michał Mazurkiewicz

Veterinary Parasitology.2008; 153(1-2): 168. CrossRef - Epidemiology and Control of Neosporosis andNeospora caninum

J. P. Dubey, G. Schares, L. M. Ortega-Mora

Clinical Microbiology Reviews.2007; 20(2): 323. CrossRef - Neospora caninum in wildlife

Luís F.P. Gondim

Trends in Parasitology.2006; 22(6): 247. CrossRef - Sero-epidemiological survey of Neospora caninum infection in dogs in north-eastern Italy

Gioia Capelli, Stefano Nardelli, Antonio Frangipane di Regalbono, Antonio Scala, Mario Pietrobelli

Veterinary Parasitology.2004; 123(3-4): 143. CrossRef