Abstract

A 59-year-old Korean man complained of a painless scrotal hard nodule and weak urine stream. The ultrasound scan revealed a 2.2-cm sized round heteroechogenic nodule located in the extratesticular area. Microscopic hematuria was detected in routine laboratory examinations. On scrotal exploration, multiple spargana were incidentally found in the mass and along the left spermatic cord. On cystoscopy, a 10-mm sized mucosal elevation was found in the right side of the bladder dome. After transurethral resection of the covered mucosa, larval tapeworms were removed from inside of the nodule by forceps. Plerocercoids of Spirometra erinacei was confirmed morphologically and also by PCR-sequencing analysis from the extracted tissue of the urinary bladder. So far as the literature is concerned, this is the first worm (PCR)-proven case of sparganosis in the urinary bladder.

-

Key words: Spirometra erinacei, sparganum, urinary bladder, scrotum, sparganosis

INTRODUCTION

Sparganosis is a parasite infection caused by the plerocercoid larvae of the genus

Spirometra, a pseudophyllidean tapeworm [

1]. Humans can be exposed to sparganosis by ingesting infected copepods with procercoids through drinking water; by consuming frogs, snakes, or rodents harboring the plerocercoids; or from poultices made of infected flesh of frogs or snakes [

1]. Many sparganosis cases have been reported in the urological organs, such as the groin, scrotum, testis, spermatic cord, epididymis, and urethra [

2]. Only 1 case of eosinophilic cystitis caused by vesical sparganosis has been reported among the literature, but it was only confirmed by a serological test, not by the sparganum worm [

2]. We report here an interesting case of genitourinary sparganosis with multiple spargana worms infiltrated into the scrotum, spermatic cord, and urinary bladder.

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old man presenting with a 2-cm sized painless movable hard mass in the left scrotum since 1 year before was admitted. He also complained of slow urine stream and hesitancy. The patient had a history of raw snake and frog ingestion during his childhood. He was a farmer living in a rural area. On physical examinations, a relatively ill-defined, 2-cm sized, round and movable hard nodule was detected in the scrotum. Routine laboratory tests revealed microscopic hematuria, but others were unremarkable. The ultrasound scan revealed a 2.2-cm sized well-defined round heteroechogenic nodule between the left epididymis and the spermatic cord.

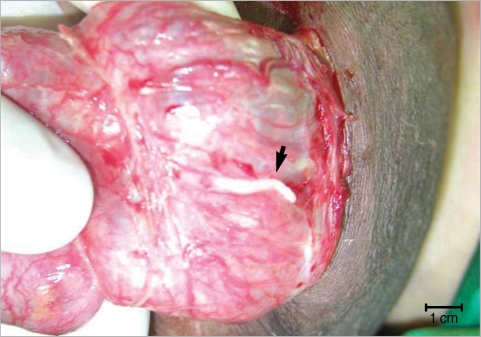

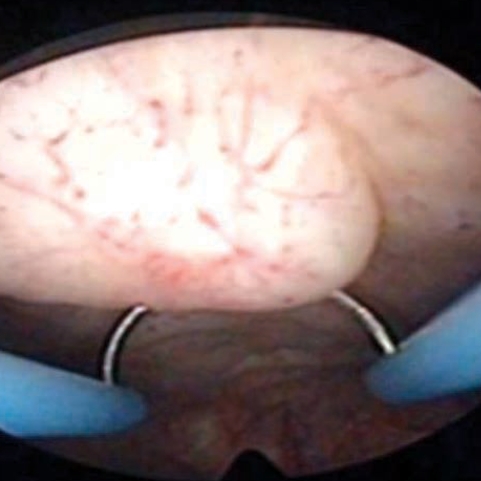

At operation, multiple spargana were found within the mass, around the spermatic cord and scrotal soft tissues (

Figs. 1,

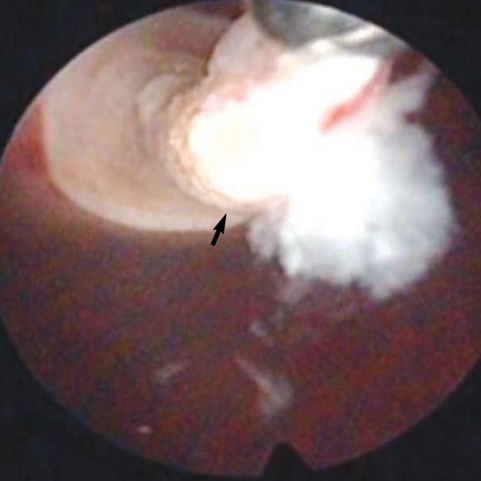

2). All identified spargana worms were completely excised. Diagnostic cystoscopy was performed consecutively to evaluate the microscopic hematuria, and a 10-mm sized small nodular mucosal elevation was found in the right side of the dome of the urinary bladder (

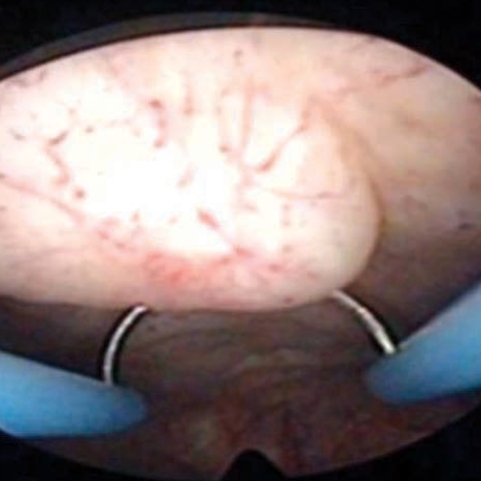

Fig. 3). Covered mucosa was removed using resectoscope, and a whitish worm-like mass surrounded by granulation tissues was found inside of the nodule (

Fig. 4). We tried to remove it by forceps, but it came apart. Histological examinations revealed a foreign body granuloma with a few infiltrates of eosinophils. In a serological test, patient's serum showed a positive reaction to anti-sparganum IgG antibody.

The larval tapeworms were morphologically identified as the spargana of Spirometra erinacei. The worm from urinary bladder was put to a PCR sequencing analysis. The PCR amplification and direct sequencing for the cox1 target fragment (353-bp in length corresponding to the positions 769-1,121 bp of the cox1 gene) were performed using the total genomic DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded samples. The cox1 sequences (353 bp) of the specimen showed 98% similarity to the reference sequences of the Japanese origin Spirometra erinaceieuropaei (GenBank No. AB-278575.1) and 90% similarity with the reference sequence of Spirometra proliferum (GenBank No. AB015753.1).

In a year post-operation, the patient underwent the serological test against the sparganum. Although the level of the IgG antibody had decreased, the result still remained positive. The patient is now on a close follow-up through physical and serological examinations.

DISCUSSION

Humans can be infected by spargana via ingestion of contaminated water, eating raw amphibian (frog) or reptile (snake) meat, or dermal contact of those meats as a poultice. The ingested spargana can invade various organs, such as the eye, subcutaneous tissues, abdominal wall, brain, spinal cord, lung, breast, and others [

3-

5]. In the case of genitourinary system, the scrotum was the most commonly affected organ by the spargana [

6]. Also an involvement of the epididymis, spermatic cord, penis, retroperitoneum, and ureter has been reported [

2,

7,

8]. So far, only 1 case of vesical sparganosis has been reported which caused eosinophilic cystitis [

9]. However, the diagnosis was based on elevated serum IgG antibodies for spargana and the histopathological findings with infiltrated eosinophils, but not by the worm. In our study, we directly removed the worm by forceps under cystoscopy from the submucosa of the bladder, and confirmed sparganosis by a PCR reaction. Therefore, this is the first case of urinary bladder sparganosis confirmed by the worm (PCR) among the literature.

Human sparganosis is an extremely rare disease, even in endemic countries, and its manifestations are diverse, such as non-specific discomforts, vague pain, palpable mass, headache, or no symptoms according to the involved organs. In our case, the patient was presented by an asymptomatic scrotal mass, and mild lower urinary tract symptoms. If microscopic hematuria was not found on the urinalysis, we could not have detected the vesical sparganosis because cystoscopic examination was not necessary for this patient. Therefore, in patients who have a suspicious history and multiple spargana in genitourinary organs, and complain of lower urinary symptoms with hematuria, the urologist should keep in mind with a high suspicion for vesical sparganosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010-0063257).

References

- 1. Norman SH, Kreutner A Jr. Sparganosis: clinical and pathologic observations in ten cases. South Med J 1980;73:297-300.

- 2. Sakamoto T, Gutierrez C, Rodriguez A, Sauto S. Testicular sparganosis in a child from Uruguay. Acta Trop 2003;88:83-86.

- 3. Wiwanitkit V. A review of human sparganosis in Thailand. Int J Infect Dis 2005;9:312-316.

- 4. Sim S, You JK, Lee IY, Im KI, Yong TS. A case of breast sparganosis. Korean J Parasitol 2002;40:187-189.

- 5. Park JH, Chai JW, Cho N, Paek NS, Guk SM, Shin EH, Chai JY. A surgically confirmed case of breast sparganosis showing characteristic mammography and ultrasonography findings. Korean J Parasitol 2006;44:151-156.

- 6. Uh HS, Kim DW, Yoo TG, Kim EK. Sparganosis infesting in the penis; a case report with review of Korean literatures. Korean J Urol 1997;38:873-876.

- 7. Lim D, Kim CS, Kim SI. Sparganosis presenting as spermatic cord hydrocele in six-year-old boy. Urology 2007;70:1223.e1-1223.e2.

- 8. Yang KM, Lee KW, Lee DH, Kim YS, Ko WJ, Lee SY. Sparganosis combined with inguinal hernia. Korean J Urol 2005;46:1366-1367.

- 9. Oh SJ, Chi JG, Lee SE. Eosinophilic cystitis caused by vesical sparganosis: a case report. J Urol 1993;149:581-583.

Fig. 1A sparganum in the left spermatic cord. Arrow shows a live worm.

Fig. 2Spargana removed from the scrotal mass, soft tissues, and left spermatic cord.

Fig. 3A small nodular mucosal elevation in the right side of the bladder dome.

Fig. 4A sparganum worm (arrow) and surrounding granulation tissue which were pulled by forceps.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Miyozite Neden Olan Parazitler

Süleyman Kaan Öner, Sevil Alkan Çeviker, Numan Kuyubaşı

Black Sea Journal of Health Science.2023; 6(3): 498. CrossRef - Sparganosis mimicking a soft-tissue tumor

Shiwangi Sharma, Rakesh Kumar Mahajan, Hira Ram, M. Karikalan, Arvind Achra

Tropical Parasitology.2021; 11(1): 49. CrossRef - A Human Case of Lumbosacral Canal Sparganosis in China

Jian-Feng Fan, Sheng Huang, Jing Li, Ren-Jun Peng, He Huang, Xi-Ping Ding, Li-Ping Jiang, Jian Xi

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2021; 59(6): 635. CrossRef - Human proliferative sparganosis update

Taisei Kikuchi, Haruhiko Maruyama

Parasitology International.2020; 75: 102036. CrossRef - Eosinophilic Pleuritis due to Sparganum: A Case Report

Youngmin Oh, Jeong-Tae Kim, Mi-Kyeong Kim, You-Jin Chang, Keeseon Eom, Jung-Gi Park, Ki-Man Lee, Kang-Hyeon Choe, Jin-Young An

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(5): 541. CrossRef - Scrotal Sparganosis Mimicking Scrotal Teratoma in an Infant: A Case Report and Literature Review

Yi-Ming Zhao, Hao-Chuan Zhang, Zhong-Rong Li, Hai-Yan Zhang

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2014; 52(5): 545. CrossRef - Multiple Sparganosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

Hong Sang Yoon, Byung Joon Jeon, Bo Young Park

Archives of Plastic Surgery.2013; 40(04): 479. CrossRef - Disseminated Sparganosis in a Cynomolgus Macaque (Macaca fascicularis)

A.-L. Bauchet, C. Joubert, J.-M. Helies, S.A. Lacour, N. Bosquet, R. Le Grand, J. Guillot, F. Lachapelle

Journal of Comparative Pathology.2013; 148(4): 294. CrossRef - SpiroESTdb: a transcriptome database and online tool for sparganum expressed sequences tags

Dae-Won Kim, Dong-Wook Kim, Won Gi Yoo, Seong-Hyeuk Nam, Myoung-Ro Lee, Hye-Won Yang, Junhyung Park, Kyooyeol Lee, Sanghyun Lee, Shin-Hyeong Cho, Won-Ja Lee, Hong-Seog Park, Jung-Won Ju

BMC Research Notes.2012;[Epub] CrossRef - A Case of Inguinal Sparganosis Mimicking Myeloid Sarcoma

Jin Yeob Yeo, Jee Young Han, Jung Hwan Lee, Young Hoon Park, Joo Han Lim, Moon Hee Lee, Chul Soo Kim, Hyeon Gyu Yi

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2012; 50(4): 353. CrossRef - Case Report: Lower Extremity Sparganosis in a Bursa

Kee-Yong Ha, In-Soo Oh

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®.2011; 469(7): 2072. CrossRef - Vulva sparganosis misdiagnosed as a Bartholin's gland abscess

Tae-Hee Kim, Hae-Hyeog Lee, Soo-Ho Chung, Boem-Ha Yi, Jeong-Ja Kwak, Hae-Seon Nam, Sang-Heon Cha

Korean Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.2010; 53(8): 746. CrossRef