Abstract

In vitro cultivation of trematodes would assist studies on the basic biology of the parasites and their hosts. This is the first study to use the yolk of unfertilized chicken eggs as a simple and successful method of ovocultivation and the first time to obtain the adult-stage of the trematode Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899 (Digenea: Brachycoeliidae). Chicken eggs were inoculated with metacercariae from the muscle of the spiny lobster, Panulirus argus (Latreille, 1804). The metacercariae were excysted and incubated for 576 hr (24 days) at 38℃ to obtain the adult stage. Eggs in utero were normal in shape and light brown color. The metacercariae developed into mature parasites that have been identified as the adult-stage found in marine turtles. The adult lobsters collected in Quintana Roo State, Mexico, showed the prevalence of 49.4% and the mean intensity of 26.0 per host (n = 87). A statistical study was performed to determine that no parasitic preference was detected for male versus female parasitized lobsters. Morphometric measurements of the adult-stage of C. solearis obtained in our study have been deposited in the National Helminths Collection of the Institute of Biology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. This study is significant because it is the first time that a digenean of the family Brachycoeliidae has been demonstrated to develop in vitro from metacercariae into adults capable of producing eggs using the yolk of unfertilized chicken eggs. Secondly, this technique allows to obtain the adult stage of C. solearis without the presence of its marine turtle host, allows us to describe the mature parasites, and thus contribute to our understanding of the biology of C. solearis.

-

Key words: Cymatocarpus solearis, metacercaria, adult, egg, in vitro cultivation, marine turtle, Mexico

INTRODUCTION

Digeneans are one of the most common groups of helminths found parasitizing vertebrates. In Mexico, after 70 years of taxonomic research, 503 species have been reported in approximately 440 of the 4,697 species of vertebrates known to occur in the country [

1]. A total of 153 digenean species are endemic or have at least been recorded only within Mexican territory [

1]. Digeneans, because of their prevalence and abundance in nature and their complex life cycles, are one of the most important groups of parasites to be considered in managing biodiversity, conservation, and as indicators for ecosystem monitoring [

1]. Due to the complex life cycle of the trematode, the presence of its particular host appears to be an important factor for the existence of these parasites. The trematode,

Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899, a member of the family Brachycoellidae, was first described in 1899, and has been found in different hosts with a wide geographic distribution. In Mexico, this parasite has been reported to infect the spiny lobster,

Panulirus argus Latreille, 1804, from the Caribbean coast of Quintana Roo State, Mexico [

2]. This spiny lobster has a high price and demand in the markets and restaurants located in the Caribbean coast of Mexico. The

P. argus fishery on the Caribbean coast is the largest in the world and one of the most important fishing resources in Mexico [

3].

Until now, there have been no records of a detailed description of the life cycle of C. solearis. The knowledge of a parasite contributes to understand essential links between them and its host, and also contributes to the basic knowledge on the biology. The technique described in this paper could assist the ability to rear developmental stages of parasites under experimental conditions for further comparative studies, which will increase the understanding of these parasites and their impact on the nature. Moreover, the ability to reproduce the complete life cycle under experimental conditions provides a model which will allow other scientists to achieve a novel and simple tool when the hosts are difficult to capture.

Parasite cultivation in vitro can be used to simulate biological conditions in the host [

4]. Digenetic trematodes have been grown on the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) of chick embryos, a technique first described by Fried [

5]. Chorioallantois specimens contain diverticulate ceca with dark brown granular material, suggesting that the parasites ingest and utilize blood from the vascular chorioallantoic membrane [

6]. A total of 23 digenean species from 14 families have been studied in chick embryos, mainly on the chick CAM [

7]. Data on some of the life cycle stages of the parasites is often absent.

The aim of this investigation was to develop a simpler technique for cultivation of and development of the metacercariae of the trematode,

C. solearis, into adults. We wanted to determine whether we could obtain adult

C. solearis utilizing unfertilized chicken eggs instead of chick embryos. To our knowledge, relatively little is known on the life cycle stages of

C. solearis. Caballero-Caballero [

8] was the first to report the adult of

C. solearis parasitizing marine turtles in Mexico; Gómez et al. [

2] described the morphology of the metacercariae of

C. solearis. Our second objective was to provide a description of the adult-stage produced in our study through ovocultivation, and to compare it with that of adults from naturally infected hosts. The present study is of significance, because it demonstrates for the first time the ability to culture and study adult

C. solearis in the absence of its definitive host, and thus builds up our knowledge of the biology of this parasite.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of parasites

Spiny lobsters (

Panulirus argus) were collected from a local fish cooperative "Vigía el Chico" in Punta Allen Quintana Roo, México (19° 45'N 87° 30'W). A total of 87 lobster tails were examined in situ and classified as either parasitized (43 tails) or not parasitized (44 tails). This was based on the detection of cysts (white spots) in the muscle, as described by Gómez et al. [

2]. The tail length to the telson was measured and the sex of each lobster determined. Six of the parasitized tails were selected and transported to the laboratory at ICMYL (Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Académica Sistemas Arrecifales, Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo, Mexico). The cysts were dissected from the abdominal muscle using a sterile scalpel, and the metacercariae were extracted from the cysts under a stereomicroscope (LEICA MZ 9.5, Wetzlar, Germany). All of the metacercariae were put in saline solution (17 ppm) containing 0.5 mg/ml streptomycin and 50 IU/ml penicillin to prevent fungal and bacterial proliferation.

Chicken eggs were obtained locally and verified to be unfertilized by the seller (n = 20 per experiment). The eggs were washed and swabbed with ethanol, and an opening was made on the uppermost surface of the shell. Then, 5 ml of the albumen was removed to provide space for the solution containing the metacercariae, which was then injected (~10 parasites/per egg) with a Pasteur pipette. The eggs were placed in a standard bacterial incubator, Gallenkamp INA 300, size 1 (Weiss-Gallenkamp, Sussex, UK). All chicken eggs were sealed with scotch-tape (transparent) and arranged in an incubator. In the first experiment, the total number of parasites incubated was 178 in 20 unfertilized eggs at 36℃; in the second trial, 174 metacercariae in 20 unfertilized eggs at 38℃. A 200 ml glass of water was kept inside the incubator to generate humidity. The eggs were monitored daily observing possible decomposition and removal of that sample, also each egg was rotated to keep the yolk from attaching to the shell. Every 3 days, an egg was opened and placed in a Petri dish with saline solution, all the worms were observed under a stereomicroscope, and each parasite found was carefully transferred to another slide glass with a pipette. The preparations were then mounted with a coverslip to flatten the specimen, and drop by drop of AFA (a mixture of 85 ml of ethanol, 25 ml of formaldehyde, and 5 ml of acetic acid) was added to the edge of the coverslip to fix the worm, which was stained with acetic carmine after the worms were made transparent with clove oil, and mounted with balsam of Canada. Further parasite observations were done with an optic microscope (LEICA DMLB 10) for better resolution. In order to determine the maturity status and to perform morphological descriptions, the parasites were observed under an optical microscope and drawings were made with the aid of a camera lucida (100 x/oil immersion magnification).

The taxonomic identification of the metacercariae and adults found in this study was based on the work of previous workers [

2,

8], and Lamothe-Argumedo (personal communication). Morphometric measurements of the adult-stage of

C. solearis obtained in vitro study (catalogue number 4333) were compared with the adult-stage specimens from naturally infected hosts (catalogue number 002543) in the National Helminths Collection of the Institute of Biology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (CNHE-IBUNAM), and the work of Caballero-Caballero [

8]. The ecological parameters, i.e., the prevalence, abundance, and mean intensity, were calculated according [

9]. This study also sets out to examine the parasitic preference between male versus female parasitized lobsters using a χ

2 test to test for an association between parasite infection and lobster sex.

RESULTS

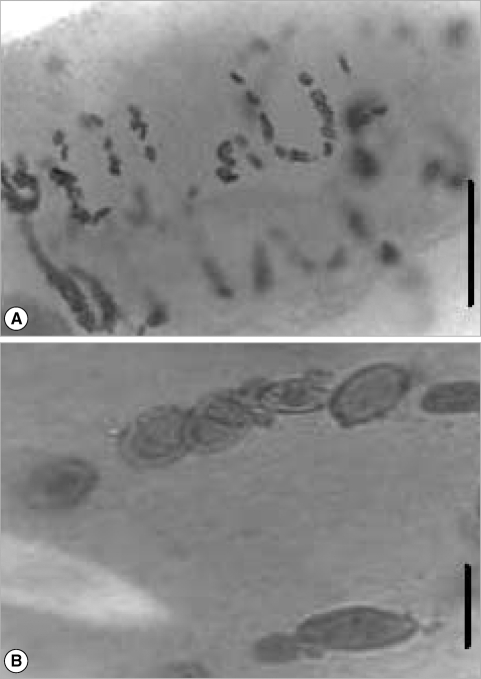

The ovoculture technique described above was successful in developing from metacercariae to adults of

C. solearis after 24 days (576 hr) at 38℃ (n = 6) and no adults were found at 36℃. The adult was identified by several characteristics, and in particular, the presence of light brown eggs containing an operculum, ovum, and vitelline cells was observed in utero, and displacement of the reproductive structures to the posterior region of the organism was seen (

Fig. 1). A complete taxonomical description was elaborated for the adultstage of

C. solearis obtained in vitro (catalogue number 4333) and the exemplar collected and deposited by Manter in 1910 in the CNHE-IBUNAM (catalogue number 002543) (

Fig. 2;

Table 1).

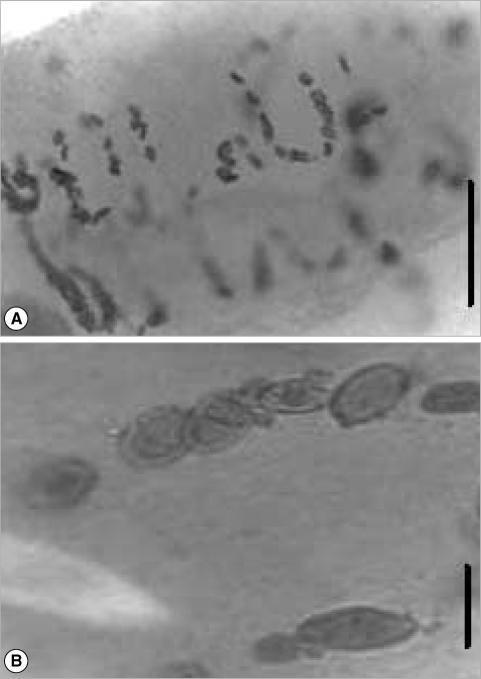

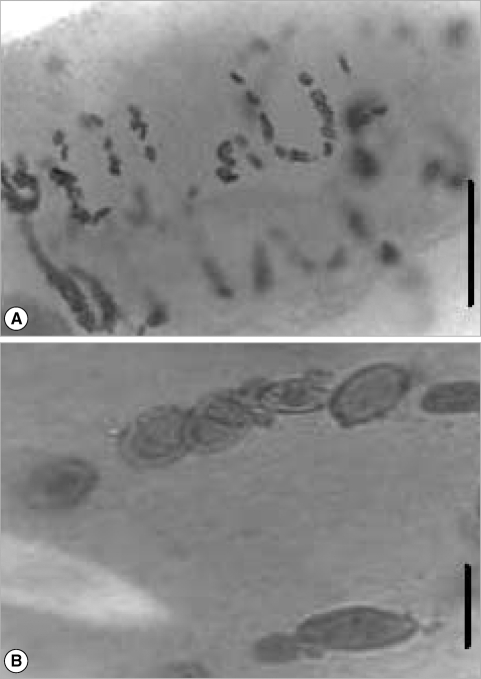

A total of 352 metacercariae recovered from the 6 lobster's abdomens were incubated in yolks of unfertilized chicken eggs. In the first experiment, the total number of parasites incubated at 36℃ was 178 and the worm's percentage recovered was 28% but any of the worms recovered were adults. In the second experiment, 174 metacercariae and the worm's percentage recovered was 38% at 38℃. The morphology of the adult specimens from the ovotechnique was compared with 2 adult specimens collected from marine turtles. The length growth of worms cultured was 2.8 ± 0.3 mm and width 1.0 ± 0.2 mm. All of the reproductive organs were well developed in these worms, and few eggs appeared in the uterus (

Fig. 3). So far, the condition at 38℃ was found better than at 36℃.

With reference to the lobster's parasitism by the host sex, this study showed that there was no parasitic preference between the 43 parasitized lobsters; we established 21 females and 22 males (χ2 = 0.023, table 3.84; fd = 0.1, α = 0.05). We found that almost 50% of the population were parasitized in the study zone (a total of 43 individuals of 87 individuals were parasitized).

The prevalence registered was 49.4%, the abundance 58.7. The mean intensity was 26 per host and the number of parasites per host varied from 33 to 109. These data are from the 352 metacercariae found in the 6 lobsters's abdomens.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first report of metacercariae of C. solearis, a digenean of the family Brachycoeliidae, which have been successfully grown in vitro into adult worms. This parasite has been successfully grown in vitro into adult worms capable of producing eggs in the yolk of unfertilized chicken eggs at 38℃. Secondly, this technique allows obtaining the adult stage of C. solearis without the presence of its marine turtle host. Therefore, in vitro cultivation of metacercariae should be helpful to obtain a great number of adult flukes.

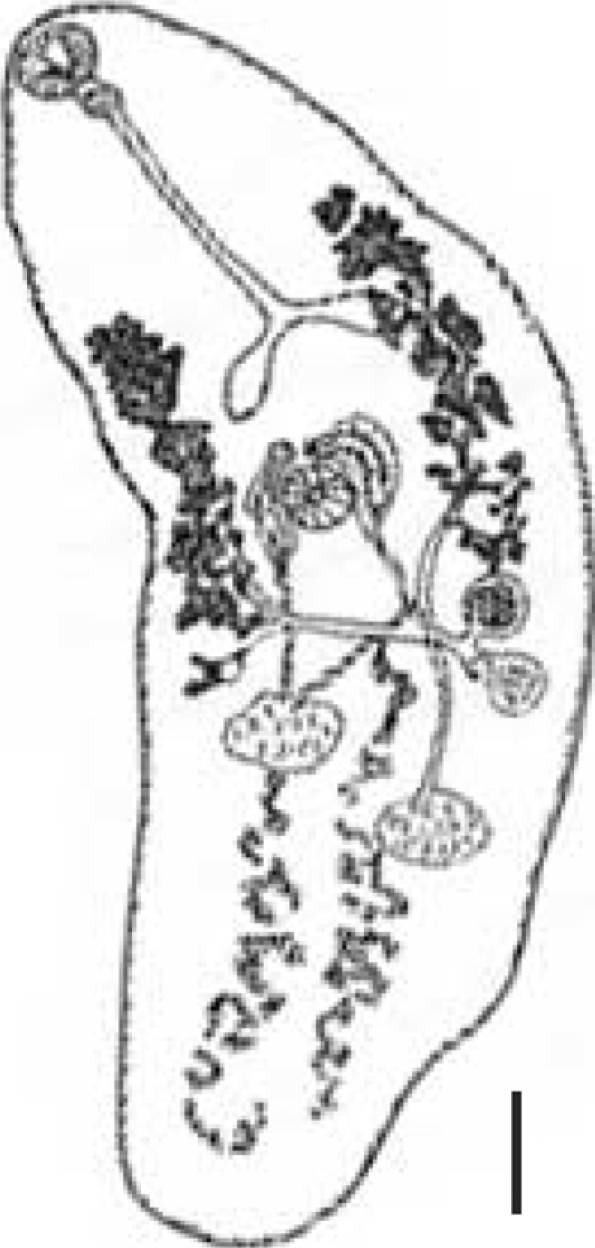

The description of the adult's internal structures and the dimension of the eggs are similar in shape and size. A comparison and taxonomic verification between the 3 kinds of adults was elaborated (

Table 1). The differences between worms collected by Manter in 1910 from natural turtle host were the higher numbers of eggs present in utero (

Fig. 2). However, the adult obtained by ovotechnique in the present study showed lower numbers of eggs, and this may indicate an early developing state egg production in utero related with experimental laboratory conditions (

Fig. 3).

In this study, the adult of

C. solearis and egg morphology was similar compared with the specimen collected from marine loggerhead turtles

Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758) by Manter in 1910 in Florida, USA (

Fig. 2) (Lamothe-Argumedo; personal communication). The adult parasite presented with a displacement of the reproductive structures to the anterior part of the body as a consequence of the quantity of eggs present in utero. The adult obtained by the ovotechnique was 2.8 ± 0.3 mm long and 1.0 ± 0.2 mm wide, larger than the Manter's adult parasite of 2.40 mm and 0.84 mm, but smaller than that reported by Caballero-Caballero [

8] in the marine turtles

Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758), the body length of 3.86 mm and width 1.41 mm.

Fried and Stableford [

7] stated that a total of 23 species from 14 families of the Digenea have been studied using chick embryos, mainly the CAM. Most species for which cultivation has produced ovigerous adults in chick embryos have been avian digeneans. Fried [

10] proposed ovocultivation and the development of a great variety of trematode parasites in fertile chicken eggs. In our study, the egg's yolk was used for the first time as a suitable environment for the culture of these brachycoeliid parasites from metacercariae to egg-producing adults.

Recent in vitro cultivation studies have shown experimental approaches using animal sera for growth and maturation of worms; gymnophallids [

11], microphallids [

12,

13], and schistosomatids [

14]. Stewart et al. [

15] developed in vitro strigeid metacercariae of

Apatemon cobitidis proterorhini and

Cotylurus erraticus to ovigerous adults in 5 days at 41℃, using a semi-solid culture medium of chicken serum and egg albumen. The inclusion of albumen as a rich source of amino acids appeared to be of nutritional benefit, insofar as it reduced the time to egg production by 1-2 days compared to that obtained by Mitchell et al. [

16] for

C. erraticus. Kook et al. [

11] cultured metarcecariae of

Gymnophalloides seoi; these authors observed that specimens did not produce eggs at 37℃ but at 41℃ the number of eggs presents was higher, suggesting that the temperature places an important role in the developmental and sexual maturation of gymnophallids in vitro. These studies were supported by recent reviews to trace the achievements of helminthological studies [

17] and of echinostomes [

18].

Cultivation of trematodes on chick embryos has been done mainly to gain basic biological information about these parasites, such as to identify metacercariae for which definitive hosts are not available. The time needed to obtain the adult stage was 24 days at 38℃ in our study, as compared to 7-10 days required for the technique of Fried [

10]. Optimum temperature varied from 38℃ [

19] to 41℃ [

20]. The apparent reason for this difference is that in the case of fertilized eggs, using chicken egg embryos, the parasites have a more accessible sanguineous food source, as they can ingest and utilize blood from the vascular CAM [

6,

21] which is not possible in unfertilized eggs. The relative nutritional contributions of tissues, secretions, exudates, and blood for helminths cultivated in ovo are not known. In the case of unfertilized eggs, even though it is not properly documented, it is possible that the parasites feed themselves from the yolk, since this is a zone where the parasites were preferentially found. Helminths grown on the CAM derive nutrients from that site by feeding on tissues, cell exudates, secretions, or blood [

7]. The ideal composition of the medium for development and egg production, however, varies according to the host species and the preferred site of infection within the gastrointestinal tract of the definitive host [

22].

A variety of parasites have been described using Fried's ovocultivation technique, for example:

Philopthalmus sp. Looss, 1899 [

5];

Himasthla quissetensis Miller and Nortup, 1926 [

23];

Echinostoma revolutum Froelich, 1802 [

21,

24-

27]. With our new technique, a retardation of trematode development caused by the absence of the embryo could explain why the adult stage took 24 days to develop. Perhaps the source of food in Fried's technique was the CAM, which may contain the disposition of food (blood) more available. In contrast, the source of food in our study is the yolk, a major source of unsaturated fatty acids [

28].

Helminthological studies in wild animals are important because they lead to a better understanding of the behavioural links between the host and parasite in nature. This knowledge may help in avoiding epizootic diseases in other ecosystems [

29]. In the case of the spiny lobster, it is important to emphasize the effects these parasites could have on fisheries in economic terms, as well as the effects of parasitizing in humans.

P. argus is an important economic resource for both Quintana Roo and Mexico as a whole [

30]. In Mexico, this trematode was recorded for the first time from the coasts of the Pacific Ocean [

8], and for the second time from the Caribbean coast [

2]. These studies have found that adult

Cymatocarpus are parasites of marine turtles, and the presence of metacercariae in

P. argus reveals that in this locality, unequivocal signals of parasitism exist. Additionally, the high levels of prevalence (49.4%) and no preference for host sex suggests that

P. argus host a stage of the parasite's life cycle. It is also important to emphasize that, in Mexico, the lobsters represent fishing resources of great importance, and this parasitism in the lobster could strongly affect its fishing ground and its market value due to the intense observed parasitism (almost 50%). Although it is unknown to what extent the parasite causes physiological damage to the host, it is obvious that a product that has observable dots in the muscle is not desirable for the consumer and thus may cause great economic losses.

In the present study, the technique applied is a valuable tool due to the ability to bypass the host in experimental conditions. In this case, in particular, the host is a marine turtle that is globally in danger of extinction [

31,

32]. Future comparison of 18S ribosomal RNA gene (or other conserved gene) sequence between the digenean collected from lobsters and

C. solearis isolated from turtles, should be conducted.

Finally, the present study shows that in vitro cultivation of trematodes would assist studies on the basic biology of the parasites and their host. This simple and successful method of ovocultivation of the trematode C. solearis (Brachycoeliidae) should be extended to other helminths, and further studies be performed in order to obtain more adult stages of parasites with complicated life cycles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author is thankful to Rafael Lamothe-Argumedo for his taxonomic knowledge, to Luis Garcia and Alma Rosa Almaral for their help in acquiring specimens and literature, and to Andrea V. Sussmann for providing editorial comments. Funding was provided to the first author by the Dirección General de Evaluación Educativa-National Autonomous University of Mexico UNAM (DGEE-UNAM) and CONACYT "Consejo Nacional Ciencia y Tecnologia, Mexico" Fellow Number: 171032. The first author appreciates the suggestions of anonymous reviewers for their contribution to improve the manuscript. This paper is dedicated to the late Jose Alvarez-Cadena, who passed away during the writing of this manuscript.

References

- 1. de Leon GPP. The diversity of digeneans (Platyhelminthes: Cercomeria: Trematoda) in vertebrates in Mexico. Comp Parasitol 2001;68:1-8.

- 2. Gómez del Prado MG, Alvarez-Cadena J, Lamothe-Argumedo R, Grano-Maldonado M. Cymatocarpus solearis a brachycoeliid metacercaria parasitizing Panulirus argus (Crustacea: Decapoda) from the Mexican Caribbean Sea. An Inst Biol 2003;74:1-10.

- 3. Briones P, Lozano E. In Cobb JS, Phillips BF eds, The spiny lobster fisheries in México. The Biology and Management of Lobsters. 1980, New York, USA. Academic Press; pp 144-157.

- 4. Chappell LH. Physiology of Parasites. 1980, 3rd ed. Glasgow and London, UK. Blackie; p 220.

- 5. Fried B. Growth of Philopthalmus sp. (Trematoda) on the chorioallantois of the chick. J Parasitol 1962;48:545-550.

- 6. Fried B. Transplantation of a monogenetic trematode, Polystomoides sp., to the chick choriallantois. J Parasitol 1965;51:983-986.

- 7. Fried B, Stableford LT. Cultivation of helminths in chick embryos. Adv Parasitol 1991;30:108-165.

- 8. Caballero-Caballero E. Tremátodos de las tortugas de México. VII. Descripción de un tremátodo digéneo que parasita a tortugas marinas comestibles del Puerto de Acapulco, Guerrero. An Inst Biol 1959;30:159-166.

- 9. Margolis L, Esch G, Holmes JC, Kuris AM, Schad GA. The use of ecological terms in Parasitology (report of an ad hoc committee of the American Society of Parasitologists). J Parasitol 1982;68:131-133.

- 10. Fried B. Cultivation of trematodes in chick embryos. Parasitol Today 1989;5:3-5.

- 11. Kook J, Lee SH, Chai JY. In vitro cultivation of Gymnophalloides seoi metarcercariae (Digenea: Gymnophallidae). Korean J Parasitol 1997;35:147-154.

- 12. Fredensborg B, Poulin R. In vitro cultivation of Maritrema novaezealandensis (Microphallidae): the effect of culture medium on excystation, survival and egg production. Parasitol Res 2005;95:310-313.

- 13. Pung OJ, Burger AR, Walker MF, Barfield WL, Lancaster MH, Jarrous CE. In vitro cultivation of Microphallus turgidus (Trematoda: Microphallidae) from metacercaria to ovigerous adult with continuation of the life cycle in the laboratory. J Parasitol 2009;95:913-919.

- 14. Chanová M, Bulantová J, Máslo P. In vitro cultivation of early schistosomula of nasal and visceral bird schistosomes (Trichobilharzia spp., Schistosomatidae). Parasitol Res 2009;104:1445-1452.

- 15. Stewart M, Mousley A, Koubkova B, Sebelova S, Marks N, Halton D. Development in vitro of the neuromusculature of two strigeid trematodes, Apatemon cobitidis proterorhini and Cotylurus erraticus. Int J Parasitol 2003;33:413-424.

- 16. Mitchell JS, Halton DW, Smyth JD. Observations on the in vitro culture of Cotylurus erraticus (Trematoda: Strigeidae). Int J Parasitol 1978;8:389-397.

- 17. Yoneva A, Mizinska-Boevska Y. In vitro cultivation of helminths and establishment of cell cultures. Exp Path Parasitol 2001;4:3-8.

- 18. Fried B, Peoples RC. In Fried B, Toledo R eds, Maintenance, cultivation, and excystation of echinostomes: 2000-2007. The Biology of Echinostomes. 2009, New York, USA. Springer Science and Business Media; pp 111-128.

- 19. Saville DH, Irwin WB. In ovo cultivation of Microphallus primas (Trematoda: Microphallidae) metacercariae to ovigerous adults and the establishment of the life-cycle in the laboratory. Parasitology 1991;103:479-484.

- 20. Irwin WB, Saville DH. Cultivation and development of Microphallus pigmaeus (Trematodes: Microphallidae) in fertile chick eggs. Parasitol Res 1988;74:396-398.

- 21. Fried B, Huffman JE. Excystation and development in the chick and on the chick chorioallantois of the metacercaria of Sphaeridiotrema globulus (Trematoda). Int J Parasitol 1982;12:427-431.

- 22. Irwin WB. In Fried B, Gracyk T eds, Excystation and cultivation of trematodes. Advances in Trematode Biology. 1997, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Florida, USA. CRC Press; pp 57-86.

- 23. Fried B, Groman GM. Cultivation of the cercaria of Himasthla quissetensis (Trematoda) on the chick chorioallantois. Int J Parasitol 1982;15:219-223.

- 24. Fried B, Grigo KL. Infectivity and excystation of the metacercariae of Echinoparyphium flexum (Trematoda). Proc Penns Acad Sci 1975;49:79-81.

- 25. Fried B, Butler MS. Infectivity, excystation and development on the chick chorioallantois of the metacercaria of Echinostoma revolutum (Trematoda). J Parasitol 1978;64:175-177.

- 26. Fried B, Pentz L. Cultivation of excysted metacercaria of Echinostoma revolutum (Trematoda) in chick embryos. Int J Parasitol 1983;13:219-223.

- 27. Fried B, Fujino T. Scanning electron microscopy of Echinostoma revolutum (Trematoda) during development in the chick embryo and the domestic chick. Int J Parasitol 1984;14:75-81.

- 28. National Research Council. (Fat Content and Composition of Animal Products). 1976, Washington DC, USA. Printing and Publishing Office, National Academy of Science; p 34.

- 29. Lamothe-Argumedo R. In González-Soriano E ed, Helmintos parásitos de animales silvestres. Historia Natural de los Tuxtlas IBUNAM. 1997, México. pp 387-394.

- 30. Lozano-Alvarez E, Briones-Fourzán P, Phillips B. Fishery characteristic, growth, and movements of the spiny lobster Panulirus argus in Bahía de la Ascension, México. Fisheries Bull (US) 1991;89:79-89.

- 31. Groombrige G. Part 1: Testudines, Crocodylia, Rhynchocephalia. The IUCN amphibian-reptilian red data book. 1982, Switzerland. (Compilation) IUCN Gland; p 426.

- 32. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). 1996, Washington DC, USA. (Appendix I, II. August 1 of 1985, and Appendix III. August 18 of 1981).

Fig. 1Adult of Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899 obtained at 576 hr from the ovotechnique culture in this study. Scale bar = 0.40 mm.

Fig. 2Adult of Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899 obtained from a marine loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta (L.), by Manter (1910) in Florida, USA. Scale bar = 0.40 mm.

Fig. 3Photomicrography of the adult Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899 cultured in this study. Images A & B were taken from an optic microscope showing the presence of eggs in utero and illustrating their similar morphology. (A) Scale bar = 0.1 mm. (B) Scale bar = 0.05 mm.

Table 1Measurements of adults of Cymatocarpus solearis Braun, 1899 cultivated by the ovotechnique in this study in comparison to those published by Caballero-Caballero (1959) in the Mexican Pacific Coast and Manter (1910) in Florida, USA

Table 1

|

Caballero-Caballero (1959) Pacific coast, Mexico (n = 1) |

Manter (1910) Florida, USA described in this study (n = 1) |

In vitro experimental technique in this study (n = 6) |

|

Body length |

3.86 |

2.40 |

2.8 ± 0.3 (2.2-3.2) |

|

Width |

1.41 |

0.84 |

1 ± 0.2 |

|

Tegument |

0.004 |

0.004 |

0.004 |

|

Oral sucker |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.22 |

0.18 |

0.15 ± 0.01 (1.04-0.17) |

|

Width |

0.25 |

0.13 |

0.18 ± 0.03 (0.16-0.19) |

|

Ventral sucker |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.20 |

0.14 |

0.15 ± 0.02 (0.15-0.17) |

|

Width |

0.21 |

0.18 |

0.18 ± 0.01 (0.17-0.19) |

|

Sucker relation: |

1:0.8 |

1:0.77 |

1:0.92 |

|

Mouth |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.10 |

0.07 |

0.08 ± 0.01 (0.06-0.09) |

|

Width |

0.11 |

0.11 |

0.05 ± 0.01 (0.02-0.06) |

|

Prepharynx |

|

|

|

|

Length |

Not mentioned |

Not observed |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

|

Width |

|

|

0.01 ± 0.01 |

|

Pharynx |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

|

Width |

0.11 |

0.07 |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

|

Esophagus |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.85 |

0.37 |

0.71 ± 0.02 (0.64-0.98) |

|

Width |

0.03 |

0.05 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

|

Ceca right |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.56 |

0.42 |

0.27 ± 0.05 (0.22-0.36) |

|

Width |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.08 ± 0.01 (0.06-0.09) |

|

Ceca left |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.61 |

0.28 |

0.20 ± 0.05 (0.18-0.28) |

|

Width |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.17 ± 0.01 (0.16-0.19) |

|

Right testis |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.26 |

0.34 |

0.24 ± 0.01 (0.22-0.27) |

|

Width |

0.33 |

0.13 |

0.20 ± 0.04 (0.18-0.23) |

|

Left testis |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.25 |

0.17 |

0.25 ± 0.01 (0.24-0.27) |

|

Width |

0.37 |

0.20 |

0.27 ± 0.05 (0.21-0.30) |

|

Seminal vesicle |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.14 |

0.18 |

0.15 ± 0.02 (0.13-0.19) |

|

Width |

0.05 |

0.15 |

0.12 ± 0.02 (0.10-0.16) |

|

Seminal receptacle |

|

|

|

|

Length |

Not mentioned |

0.36 |

0.10 |

|

Width |

|

0.15 |

0.08 |

|

Ovary |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.18 |

0.13 |

0.11 ± 0.01 (0.09-0.13) |

|

Width |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.10 ± 0.02 (0.09-0.13) |

|

Eggs |

|

|

|

|

Length |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.04 ± 0.02 (0.02-0.05) |

|

Width |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.02 ± 0.02 (0.01-0.03) |

|

Distance of cecal bifurcation to anterior zone |

1.44 |

0.68 |

1.17 |

|

Host |

Turtle Chelonia mydas

|

Turtle Caretta caretta

|

Ovoculture technique |