Abstract

Severe tick infestation was found in a hare in a suburban area of Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China. We sampled ticks and identified them based on their morphologic characteristics. Three species, Ixodes sinensis, which is commonly found in China and can experimentally transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides, and Haemaphysalis longicornis which can transmit Lyme disease were detected with an optical microscope and a stereomicroscope. Risk of spreading ticks from suburban to urban areas exists due to human transportation and travel between the infested and non-infested areas around Nanchang.

-

Key words: Ixodes sinensis, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides, Haemaphysalis longicornis, tick infestation, hare

INTRODUCTION

Some varieties of diseases possess the same hallmarks of which are transmitted between humans and animals related to arthropod vectors. They obtained the name of arthropod-borne diseases (ABD) or vector-borne diseases (VBD). However, we sometimes give these diseases the name after the systematic group they belong, i.e., mosquito-borne diseases (MBD) or tick-borne diseases (TBD). VBD always earn public health importance in subtropical and tropical regions, and they were recently converted to public health problems from a neglected matter in temperate regions [

1,

2]. Attention should be paid on VBD progress in the cost of climate change [

3-

5] and developed transportation [

6,

7].

In China, 6 kinds of diseases, namely, plague, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), dengue fever, malaria, kala-azar, and filariasis, out of 38 statutory communicable diseases belong to VBD according to legislation issued in 2004 [

8]. Once a disease is added up to statutory communicable diseases in China, it suggests severity of this disease to public health. TBD is an important member of VBD, only subordinate to MBD[

9]. The causation of TBD is caused by tick bite, and further explained due to intracelluar pathogens, including several species of bacteria, helminths, protozoa, and viruses [

10], in addition to cases of tick paralysis. TBD is reported in some limited districts of China in recent decades [

11-

13], with characteristics of sporadic occurrence, low mortality, occurrence in site representing abundant meadows and bushes, related to profession and preventive behaviors, including wearing cloths and utilizing tick repellents.

The tendency of incidence of TBD has currently altered a little. It is widely reported by websites that about 280 cases of TBD and more than 10 mortalities were recorded in Henan, Hubei, Shandong, Anhui, and Jiangsu provinces, China between May 2007 and June 2011. Some TBD cases can be regarded as serious cases. All the estimated 280 cases were confirmed by clinical diagnosis and experimental tests. A new name of this kind of TBD is acquired as fever with thrombocytopenia (FT), named by China Center for Diseases Control and Prevention according to the cardinal symptoms of this new tick-borne disease. FT is produced by a new type of Bunyamwera virus of the Bunyaviridae family [

14]. Control measures related to ticks and FT were newly reformed. These treatments will do a favor to reduce tick bites and its relative diseases.

We report here a severe tick infestation in a hare in a suburban area of Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China, with special reference to its potential risk for transmitting TBD to humans.

CASE RECORD

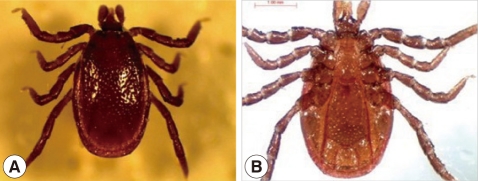

Tens of thousands of tick infestation was firstly observed in a hare in Nanchang, China. Ticks infested the hare around its body. High tick density belonged to the ear back of the hare. Many ticks sucked the hare blood to expand its body size 20-30 times larger than themselves (

Fig. 1). Tweezers were employed to pull quickly ticks out from the hare corpse when they relaxed. The operation mentioned above made sure no catitulum leaving in the hare corpse. Nearly 30 ticks were sampled for advanced identification. Every tick specimen was put into a mixture 70% ethanol with several drops of glycerin to protect the specimens against fragility. After sample, the hare corpse was laden on a steel mesh (knit following the scale of 1.5 cm width by 1.5 cm length with a 0.25 cm wire diameter) with 50 cm width×50 cm length at 30 cm height. The litter was accumulated under the steel mesh, which was covered with alcohol and then ignited. Many ticks dropped from the intense heat and burnt. The ticks dropped outside of the fire were collected with tweezers and put into the fire. The hare corpse after the treatment was buried at least 0.5 m in depth with earth.

Incidence of the hare death occurred in suburban regions of Nanchang, China. A great many of weeds, shrubs, bushes, and trees grew there with high density. A survey on plant species composition was presented briefly as follows: The family Gramineae mainly consisted of the short weeds. Shrubs and bushes exhibited the family Leguminosae frequently and some Gramineae family rarely. Trees had Paulownia fortunei, Broussonetia papyrifera, Ligustrum lucidum, and so on. We utilized tick drags made of a coarse cloth with 1 m in both length and width, in favor of tick attachment, to determine the tick density on the floor of meadowland and forestland. Drags were ornamented with 2 sticks cross the ends, one for helpful hold with hands through a belt, the other one for its weight enough to reach the meadow. The tick density of meadowland showed 0.3 ticks per 1 m2, denoting the high tick density. The tick density of the forestland had no test for its difficulty in crossing the Miscanthus floridulus belt.

DESCRIPTION OF TICKS

The ticks were fixed with 70% ethanol adding drops of glycerin and stereoscopically confirmed their species. Three tick species which have distinctive morphology each other in the sampling were distinctly tested in the lens. The morphologic characteristics were described in detail and then the identification of 3 species was presented at the end of description of the species.

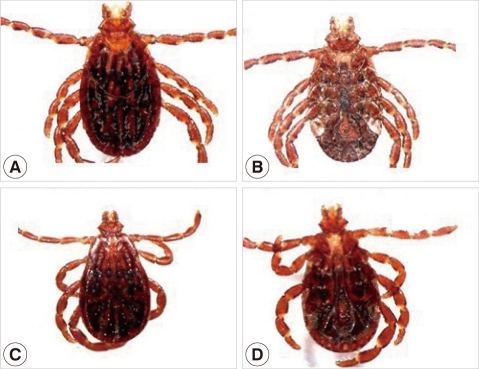

Pictures of the first male tick species are shown in

Fig. 2. The scutum had no spot on the background. No eyes were observed on the lateral edges of the scutum. The pedipalp was longer than the chelicera (

Fig. 2A). Basis capituli showed no cornua. Auricle saw as small and dull, sometimes not obvious. Coxa 1 had a slender internal spur, whose end reach but not go beyond the front edge of coxa 2. Four trochanters and other 3 coxae also had spurs, each coxa had slightly longer spurs than that of each trochanter correspondingly. Genital plate turned wider and wider from anterior to posterior parts. The anus was embraced by inverse U-shaped pre-anal groove. The circular spiracular plate was located on the ventrolateral surface posterolaterally to the coxa 4. The anal plate changed outward when went backward. The adanal plate was dramatically wider in the anterior segment than the posterior one (

Fig. 2B). Based on these morphologic features, we identified this species as

Ixodes sinensis Teng

The second female tick has features as follows: The distinct scapula was located on the anterior scutum. The scutum had the shape of cat head contour. The eyes were located on lateral edges of the scutum, and the basis capituli formed the shape of hexagon (

Fig. 3A). Coxa 1 had 2 medium-sized spurs, whose external spur was shorter than the internal one. All of 3 other coxae had shorter external spurs in comparison with that of coxa 1 (

Fig. 3B). For male ticks, internal crack in coxa 1 was narrow, whose size was lower than the internal spur. The external spurs from coxa 2 to coxa 4 were short. There was an internal spur in coxa 4 (

Fig. 3D). The anus was embraced by Y-shaped anal groove posteriorly. The adanal plate was sickle-shaped. The accessory plate with a sharp end was small. The comma-shaped spiracular plate was large (

Fig. 3B, D). According to these descriptions, these ticks were identified as

Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides Supino.

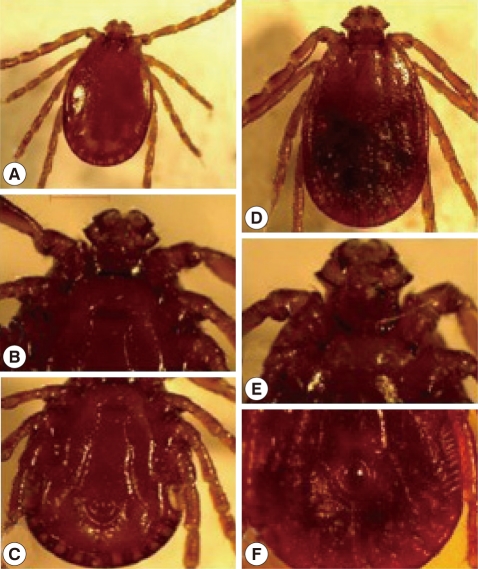

In the last species, the article 3 in the pedipalp was wide and short, and the width was approximately 2 times higher than the length. Two spurs were respectively arranged in the dorsal and ventral sides of the article 3 in the pedipalp of adult ticks. Compared to the dorsal spur, the ventral one was longer, which reached the center of article 2. No eyes were observed on the lateral edges of the scutum (

Fig. 4A, B, D, E). The anus was embraced by Y-shaped anal groove posteriorly (

Fig. 4C, F). Male ticks had characteristics, including a long oval scutum, notable lateral groove whose front end came up to the anterior third of the scutum, and posterior end reaching to the first festoon (

Fig. 4A). Female ticks had hallmarks, such as the subcylindrical scutum, long and distinct cervical groove (

Fig. 4D), subcylindrical peritreme, slender and sharp internal spur of coxa 1 (

Fig. 4E), short internal spurs which went beyond the posterior margin from coxa 2 to coxa 4, respectively (

Fig. 4E, F). Based on these morphological features, we identified this species as

Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann.

DISCUSSION

This severe tick infestation in a wild hare emerged at the first time in Nanchang, China according to our experiences and available literature in public publishing. The causes of the hare death are speculated to be huge blood loss. Many ticks sucked blood to expand its body size 20-30 times larger than themselves.

In the tick infestation, dense plantation forms the natural landscape around the scene. The meadow is the best breeding field of ticks for proper conditions, which further facilitates increased tick proliferation and density. Ticks favor enough shade and abundant humidity from the meadow. Occurrence of ticks living here generates much possibility. In the forestland, we surveyed a variety of weeds which may be used as foodstuffs by hares. A conclusion we reached was that the dead hare might have inhabited the forestland. Shade, humidity, and the host are the decisive factors for ticks completing their life history [

15,

16].

Risk consequences, that the ticks can infest humans who are residents working and living in the field near the hares infestation site, or travel around the field, will be produced based on the former deduction. Humans infested by ticks may carry ticks to other places without tick infestations. Ticks removed from the human host or leaving by themselves stay and lead their continuous life in a new habitat, where they may occur in the great urban park, and have appearance in the artificial plantation from residential areas or a public place. The frequency of human exposures to these areas will increase the potential risk of tick infestations. This risk can be interrupted by human behaviors that they detect ticks themselves and each other, and remove any ticks attaching on cloths or bodies before leaving the possible tick-infesting place. They should also wear protective clothings when entering the fruit or vegetable gardens, which may significantly increase the danger of human infestations. They may also need some chemical protections, including tick repellents. Zhang et al. [

17] showed DEET active ingredients as a good choice against ticks at least during 3-4 hr if applied on clothing and shoes.

A case of tick-bite in a woman happened only after 2 days when the tick infestation of the hare was informed to the public. The woman visited us for help together with the tick that bit her. We were certain that the tick species was I. sinensis. This tick bite in a woman indicates some tick invasion in the residential area of Nanchang, China. This may also imply that the human population in Nanchang are at an increasing risk of exposure to tick-borne pathogens. Therefore, tick surveillance and control programme should be operated in accordance with the tick ecology, biology, and other characteristics.

References

- 1. Goddard J. Infectious diseases and arthropods. 2008, 2nd ed. Humana Press; p VII.

- 2. Luz PM, Struchiner CJ, Galvani AP. Modeling transmission dynamics and control of vector-borne neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e761.

- 3. Gould EA, Higgs S. Impact of climate change and other factors on emerging arbovirus diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009;103:109-121.

- 4. Pongsiri MJ, Roman J, Ezenwa VO, Goldberg TL, Koren HS, Newbold SC, Ostfeld RS, Pattanayak SK, Salkeld DJ. Biodiversity loss affects global disease ecology. Bioscience 2009;59:945-954.

- 5. Gray JS, Dautel H, Estrada-Pena A, Kahl O, Lindgren E. Effects of climate change on ticks and tick-borne diseases in Europe. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2009;2009:593232.

- 6. Ma G, Sun C, Zhao N, Zhang X. Major prevalent trends of tick-borne disease in China and its prevention and control measures. J Agri Sci Technol 2011;13:105-109.

- 7. Pfeffer M, Dobler G. Emergence of zoonotic arboviruses by animal trade and migration. Parasit Vectors 2010;3:35.

- 8. The 10th national people's congress standing committee of People Republic of China Resource. People.com.cn. Beijing. 2002. cited 2011 June 6. Available from http://www.people.com.cn/GB/14576/28320/36780/36783/2757228.html

- 9. Romi R. Arthropod borne diseases in Italy: From a neglected matter to an emerging health problem. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2010;46:436-443.

- 10. Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology 2004;129:S3-S14.

- 11. Huo Q, Wan K, Zhang Z, Shang Z, Zhu G. Survey of sera antibody against Borrelia burgdor in the patients suspected with tick borne encephalitis. Chin J Vector Biol Control 1997;7:127-128.

- 12. Pan L. Review of tick species and tick borne diseases in Fujian Province, China. Strait J Prev Med 2011;17:21-23.

- 13. Gao D, Zhang X. Human Granulocytic Ehrichia (HGE), a new tick borne disease in China. Acta Parasitol Med Entomol Sin 1999;6:185-187.

- 14. Qin S. Ixodes persulcatus and its relative diseases. Anim Husbandry Vet Med 2011;17:15-16.

- 15. Estrada-Peña A. Climate, niche, ticks, and models: what they are and how we should interpret them. Parasitol Res 2008;103:S87-S95.

- 16. Walker AR. Eradication and control of livestock ticks: biological, economic and social perspectives. Parasitology 2011;138:945-959.

- 17. Zhang J, Sun J, Shi J, Ni P, Sun JP. Observation on repellent efficacy of DEET to ticks. Jiangsu Prev Med 2000;11:62-63.

Fig. 1A wild hare infested with numerous ticks on the ear, back, and scapular regions. Note the engorged ticks.

Fig. 2

Ixodes sinensis, males. A, dorsal view; B, ventral view.

Fig. 3

Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides, males (A, B) and females (C, D). A, dorsal view of a male tick; B, vental view of a male tick; C, dorsal view of a female tick; D, ventral view of a female tick.

Fig. 4

Haemaphysalis longicornis, males (A-C) and females (D-F), A, D, dorsal views; B-C, E-F, ventral views.