Abstract

Dirofilariasis is a rare disease in humans. We report here a case of a 48-year-old male who was diagnosed with pulmonary dirofilariasis in Korea. On chest radiographs, a coin lesion of 1 cm in diameter was shown. Although it looked like a benign inflammatory nodule, malignancy could not be excluded. So, the nodule was resected by video-assisted thoracic surgery. Pathologically, chronic granulomatous inflammation composed of coagulation necrosis with rim of fibrous tissues and granulations was seen. In the center of the necrotic nodules, a degenerating parasitic organism was found. The parasite had prominent internal cuticular ridges and thick cuticle, a well-developed muscle layer, an intestinal tube, and uterine tubules. The parasite was diagnosed as an immature female worm of Dirofilaria immitis. This is the second reported case of human pulmonary dirofilariasis in Korea.

-

Key words: Dirofilaria immitis, dirofilariasis, pulmonary dirofilariasis

INTRODUCTION

Dirofilaria immitis (the canine heartworm) is a filarial nematode naturally hosted by dogs, cats, foxes, muskrat, raccoons, and bears [

1,

2]. Adult worms live in the right heart of these animals and produce a debilitating disease. This filarial nematode is transmited by mosquitoes [

2].

When an infected mosquito takes blood from a human, the larvae of

D. immitis invade and develop for a time in cutaneous tissues, migrate to the right heart ventricle where they eventually die [

3]. The fragments of worms may reach the pulmonary arteries and lodge in a small caliber vessel to cause infarction or embolism events. These pathophysiological events are represented with granulomatous coin lesions [

4].

Patients with pulmonary dirofilariasis are usually asymptomatic; however, occurrence of cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, and wheezing has been described in some patients [

5]. Eosinophilia, commonly relevant in parasite infections, are present only in 15% of patients with pulmonary dirofilariasis [

3]. Usually, a non-calcified, peripheral coin lesion or nodule is seen in chest x-ray or computed tomography (CT) [

5]. Pathologically, spherical subpleural infarct with a central thrombosed artery containing the parasite in stage of degeneration is most commonly seen [

4-

6].

In the Republic of Korea (=Korea), the first case of human pulmonary dirofilariasis was reported in 2000 [

7]. In this report, we describe a second Korean case of pulmonary dirofilariasis which mimicked lung cancer.

CASE RECORD

A 48-year-old male was referred to Seoul National University Hospital after a routine check-up at a local hospital due to abnormal findings seen in chest CT. The patient had no significant past medical history. He was an ex-smoker (quit 10 years ago) and was a social drinker. He had a pet dog, but the dog died 3 years ago from unidentified parasite infection.

The patient had no abnormalities on physical examination. Complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell count of 6.86×103/µl (normal: 4.0-10.0×103/µl), a hemoglobin concentration of 14.5 g/dl (normal: 14-18 g/dl), and a platelet count 267×103/µl (normal: 130-450×103/µl). The differential count showed neutrophils at 36.1%, lymphocytes at 51.2%, and eosinophils at 1.5%. The C-reactive protein level was 0.02 mg/dl (normal: ≤0.5 mg/dl). Serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, magnesium, calcium, and liver function test were all within normal limits. The spirometry was normal; FVC 4.95L (105% of predicted), FEV1 3.77L (107% of predicted), and FEV1/FVC (76%). Tumor markers CEA and CYFRA were within normal range.

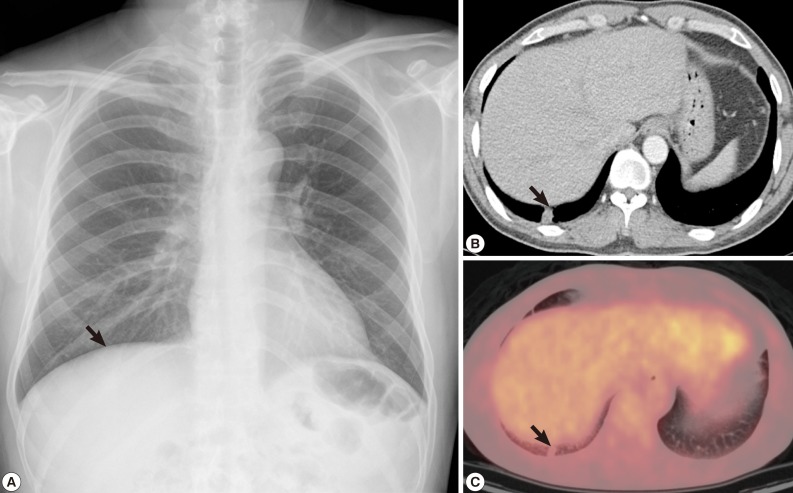

In chest radiography, a nodular opacity was found at the right lower lobe (

Fig. 1A). The chest CT showed a 1.2×1.0 cm sized subpleural solitary pulmonary nodule at the right lower lobe. Although it looked as a benign inflammatory nodule such as cryptococcal infection, malignancy could not be excluded (

Fig. 1B). On positron emission tomography (PET) image, the small subpleural nodule at the right lower lobe showed minimal increased fludeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (Standardized uptake value [SUV] 1.25) (

Fig. 1C).

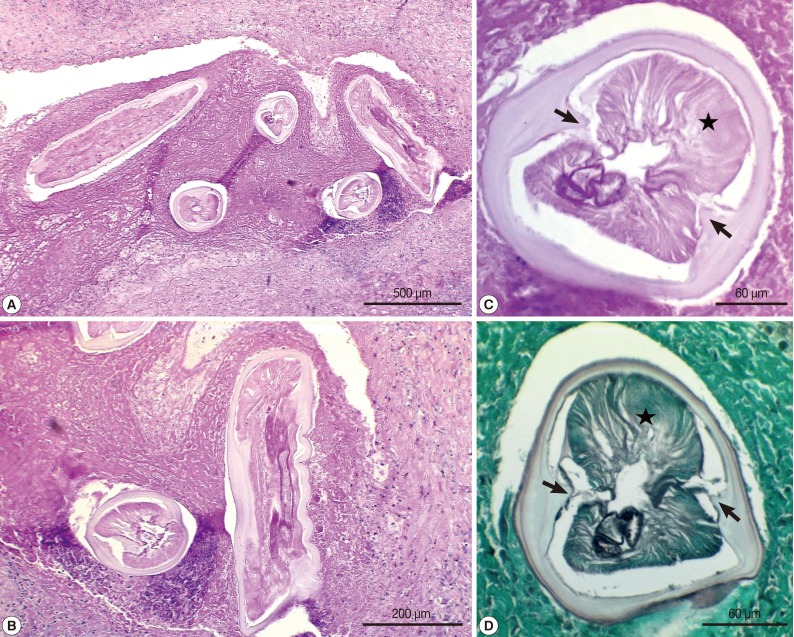

At first we considered a percutaneous needle biopsy for diagnosis, but biopsy was considered not technically feasible due to the location of the nodule. The nodule was successfully removed by video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection. Macroscopic examination of the resected mass revealed a gray, firm, and well-demarcated tumor, measuring 1.2×1.0×0.7 cm, with slight pleural indentation and central necrosis, located in the right lower lobe of the lung. Microscopically, chronic granulomatous inflammation which was composed of coagulation necrosis with rim of fibrous tissues and granulations was recognized. In the center of the necrotic nodules, a degenerating parasitic organism was found (

Fig. 2). The parasite was a nematode larva and had prominent internal cuticular ridges and thick cuticle, a well-developed muscle layer, an intestinal tube, and uterine tubules. The diameter of the worm was approximately 240 µm. Based on these morphologic features, the worm was identified as

D. immitis, an immature female worm.

After surgical resection, the patient was discharged without any complications and is being followed up in healthy conditions.

DISCUSSION

Human pulmonary dirofilariasis was first reported in 1887, when De Magalhães documented the discovery of a single male and a single female filarial worm in the left ventricle of a boy from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [

8,

9]. In 1961, Dashiell reported the first case involving the lung [

10]. After then, several hundreds of human dirofilariasis cases were reported around the world [

11,

12]. Usually

D. immitis invades the lungs in human cases, but reports of human dirofilariasis involving other organs like the subconjunctiva, liver, and subcutaneous sites are also available [

11].

In Korea, the first case of human pulmonary dirofilariasis was reported in 2000 [

7]. Another case of dirofilariasis in the liver reported in Korea [

13] was actually a misdiagnosis of hepatic capillariasis [

14]. The chest CT images and pathologic findings of our case were similar to the first Korean dirofilariasis case [

7]. However, our case is the first to show additional PET imaging. In our case, PET-CT was performed for differential diagnosis of malignancy, and the PET-CT showed a small subpleural nodule at the right lower lobe with minimal increased FDG uptake (SUV 1.25).

In the life cycle of

D. immitis, the dog is the principal host, though other suitable hosts include cats, wolves, coyotes, and foxes. Mosquitoes of

Aedes,

Culex, or

Anopheles spp. are the normal vector-intermediate host, but more than 60 species of mosquitoes in 6 genera are capable of propagating the development of

D. immitis [

8]. In the usual life cycle, the sexually mature female worm resides in the dog's right ventricle and sheds thousands of microfilariae into the blood stream. When a mosquito bites the dog, it ingests the microfilariae. Over the next 10 to 16 days, the larvae develop into the infective stage in the mosquito [

3]. In humans, the infective stage larvae of

D. immitis is injected by the mosquito bite. Human are the "dead-end host" since larvae cannot develop into adults in humans [

4]. In our case,

D. immitis was an immature female worm.

Human pulmonary dirofilariasis is usually discovered during routine health examinations because it does not cause notable symptoms. It is seen as a well-circumscribed, non-calcified, peripheral coin lesion or nodule. The nodule can measure from 0.8 to 4.5 cm in diameter [

5]. Pulmonary nodules caused by dirofilariasis should be differentiated from malignant lesions. The present case also needed tissue confirmation to exclude malignancy.

Usually, the pulmonary lesion is a spherical nodule that upon gross examination appears as a well-circumscribed, spherical, grayish-yellow nodule 1 to 3 cm in diameter, surrounded by normal lung parenchyma [

8]. On microscopic examinations, there is a central core of necrosis surrounded by a granulomatous zone of tissues. Peripherally the lesions are surrounded by fibrous tissues. In our case, the nodule was chronic granulomatous inflammation composed of coagulation necrosis with rim of fibrous tissues and granulations.

Dirofilaria infections can be diagnosed on the basis of worm morphology, such as the thick multilayer cuticle with lateral internal ridges, large lateral cords, and coelomyarian musculature. In cross sections,

D. immitis measures 100-300 µm in diameter and possesses a multilayered curicle with a thickness of 10-25 µm [

8]. The present case showed worm structures such as prominent internal cuticular ridges, no external cuticular ridges, thick cuticle, well-developed muscle layer, and presence of an intestinal tube. The diameter of the worm was 240 µm, which was compatible with a

D. immitis immature female worm.

Notes

-

We have no conflict of interest related with this report.

References

- 1. Milanez de Campos JR, Barbas CS, Filomeno LT, Fernandez A, Minamoto H, Filho JV, Jatene FB. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: analysis of 24 cases from Sao Paulo, Brazil. Chest 1997;112:729-733.

- 2. Solaini L, Gourgiotis S, Salemis NS, Solaini L. A case of human pulmonary dirofilariasis. Int J Infect Dis 2008;12:e147-e148.

- 3. Asimacopoulos PJ, Katras A, Christie B. Pulmonary dirofilariasis. The largest single-hospital experience. Chest 1992;102:851-855.

- 4. Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Paolino S. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis. Histopathology 1996;29:69-72.

- 5. Flieder DB, Moran CA. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: a clinicopathologic study of 41 lesions in 39 patients. Hum Pathol 1999;30:251-256.

- 6. Kochar AS. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis. Report of three cases and brief review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 1985;84:19-23.

- 7. Lee KJ, Park GM, Yong TS, Im K, Jung SH, Jeong NY, Lee WY, Yong SJ, Shin KC. The first Korean case of human pulmonary dirofilariasis. Yonsei Med J 2000;41:285-288.

- 8. Shah MK. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: review of the literature. South Med J 1999;92:276-279.

- 9. Miyoshi T, Tsubouchi H, Iwasaki A, Shiraishi T, Nabeshima K, Shirakusa T. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: a case report and review of the recent Japanese literature. Respirology 2006;11:343-347.

- 10. Dashiell GF. A case of dirofilariasis involving the lung. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1961;10:37-38.

- 11. Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Gustinelli A. Dirofilarial human cases in the Old World, attributed to Dirofilaria immitis: a critical analysis. Histopathology 2009;54:192-204.

- 12. Muro A, Genchi C, Cordero M, Simon F. Human dirofilariasis in the European Union. Parasitol Today 1999;15:386-389.

- 13. Kim MK, Kim CH, Yeom BW, Park SH, Choi SY, Choi JS. The first human case of hepatic dirofilariasis. J Korean Med Sci 2002;17:686-690.

- 14. Pampiglione S, Gustinelli A. Human hepatic capillariasis: a second case occurred in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2008;23:560-561.

Fig. 1Radiographs of the dirofilariasis patient. (A) A nodular lesion in the right lung found incidentally on chest x-ray. (B) Chest CT demonstrated a solitary pulmonary nodule in the right lower lobe. (C) PET also revealed a small subpleural nodule at the right lower lobe with minimal increased FDG uptake (SUV 1.25).

Fig. 2Histopathological features of the resected granulomatous nodule containing a larval nematode, Dirofilaria immitis. (A, B) The nodule was chronic graulomatous inflammation composed of coagulation necrosis with rim of fibrous tissues and granulations. In the center of the necrotic nodules, sections of a degenerating parasitic organism, D. immitis, was found. H-E stain. ×40 (A), ×100 (B). (C, D) Transverse sections of the larva showing characteristic structures of bilateral internal cuticular ridges (arrow) and musculatures (star) which are consistent with D. immitis. H-E (C) and methenamine silver stain (D). ×400 (C, D).